In this essay, we’ll look at how the costs of excessive regulation were further exposed by the need to respond quickly and effectively to the COVID-19 virus, leading to necessary deregulation.

As the Wall Street Journal reported:

The Trump Administration’s long parade of deregulation—on everything from Title IX, to net neutrality, to environmental-impact statements, to joint employers—is among its biggest achievements. Amid the coronavirus pandemic, this work has thankfully continued. In reaction to Covid-19, federal agencies and departments have taken more than 600 regulatory actions, many of them temporary, per the White House’s tally. Truck drivers hauling emergency supplies have more flexibility about hours on the road. Seniors on Medicare can consult doctors by iPhone. Colleges can ramp up distance learning without the usual red tape. On Tuesday the Administration entered the next phase of pandemic deregulation. At a cabinet meeting, President Trump signed an executive order telling government agencies to “combat the economic consequences of COVID-19 with the same vigor and resourcefulness with which the fight against COVID-19 itself has been waged.” This means going on the hunt for rules “that may inhibit economic recovery.”

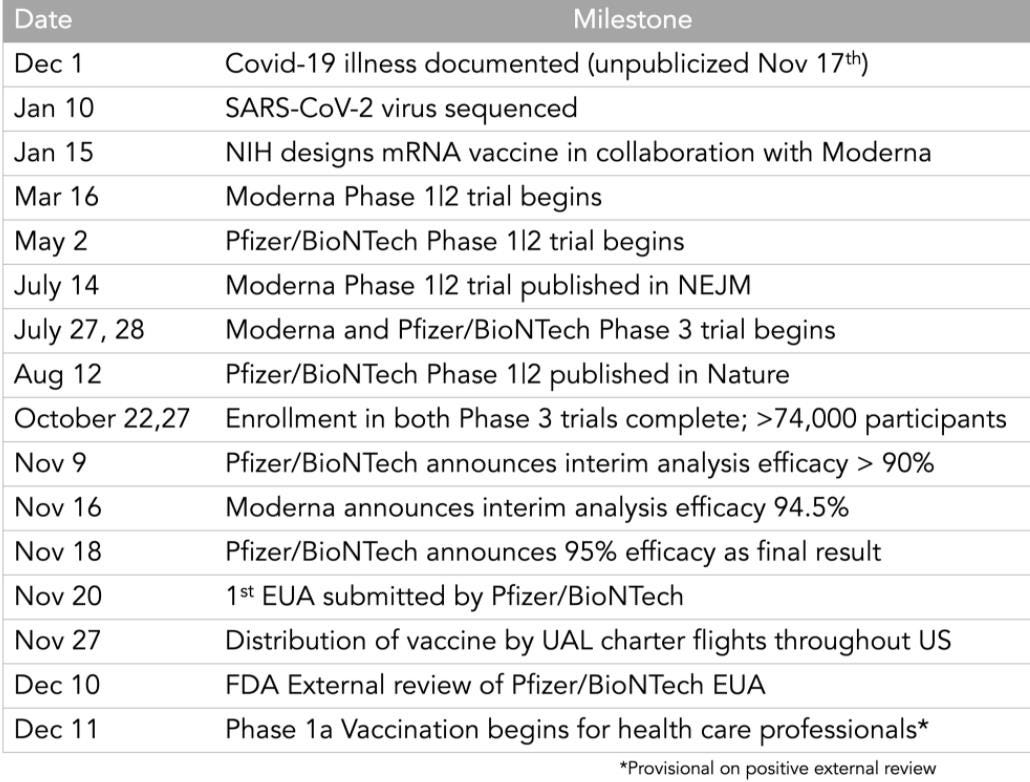

As recounted by Eric Topol, the Trump Administration’s “Operation Warp Speed”

will go down in history as one of science and medical research's greatest achievements. Perhaps the most impressive. I put together a preliminary timeline of some key milestones to show how several years of work were compressed into months … Moderna has a head-start [on a vaccine], so why didn’t their Phase 3 trial finish first? Part of Operation Warp Speed, they were requested to slow down enrollment to get better minority representation [according to the New York Times article here].

As Graham Allison writes in the Wall Street Journal, the speed of the vaccination program was the result of free markets and Operation Warp Speed, a federal program designed to remove regulations that would unreasonably hinder vaccine development:

There are clearly only two primary causes behind the Covid-19 vaccine. The first was the capitalist system, which facilitated competition between private, profit-seeking biotech and pharmaceutical companies to produce a lifesaving product. Like charities, universities, government agencies and pretty much everyone else, these organizations want to do good. But companies like Germany-based BioNTech, its Boston-based competitor Moderna, and the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer have also been racing for a pot of gold at the end of this rainbow. There would be no Covid-19 vaccine today had there been no venture capitalists prepared to invest before a product or profit was visible, no corporate leadership willing to double down with the companies’ own money in the spring to fund a crash effort to produce a vaccine by year-end, and no researchers pursuing a dream about mRNA as an unprecedented route for vaccines. Second is Operation Warp Speed. Had Mr. Trump not created the initiative, appointed as its leader a man who knows the vaccine development world, and given him license to spend $10 billion outside normal contracting procedures, Covid-19 vaccines would still be only works in progress. Even after they were finally approved, the vaccines’ distribution could have been long delayed. Imagine a world in which Mr. Trump had not appointed as deputy head of the operation a general who knows logistics and had the authority to write contracts with FedEx and UPS to book space on their airplanes and in their network of distribution centers. So as Americans now look forward to getting vaccinated and resuming our normal lives, we should pause to give thanks to a remarkable group of scientists and entrepreneurs whose capitalism-fed competitive drive pushed them to venture into the unknown—for fortune and fame. And to a deeply flawed, often dysfunctional disrupter in chief who in this case certainly did a good thing.

University of Chicago economists “found that accelerating the arrival of the vaccines by six months was worth $1.8 trillion to the U.S. economy—and more to the rest of the world.”

Problems with the distribution of the vaccine occurred largely at the state and local level. As summarized by Scott Atlas, a professor at the Stanford University Medical Center:

Americans need to understand three realities. First, all 50 states independently directed and implemented their own pandemic policies. In every case, governors and local officials were responsible for on-the-ground choices—every business limit, school closing, shelter-in-place order and mask requirement. No policy on any of these issues was set by the federal government, except those involving federal property and employees.

As important as distributing a COVID-19 vaccine should have been, some states and localities were slow in actually distributing the vaccines they initially received. As the Wall Street Journal reported in January, 2021:

The Trump Administration said Tuesday it would release vaccine doses that it had been holding back for second inoculations and send more shots to states that are administering them faster. Thank you. This should speed up vaccinations by putting more pressure on states to relax the bureaucratic and political controls that have slowed the rollout. “Every vaccine dose that is sitting in a warehouse rather than going into an arm could mean one more life lost or one more hospital bed occupied,” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a press briefing. He’s right. Only 9.3 million of the 27.7 million vaccine doses that have been shipped to states have been administered.

As the Wall Street Journal reported a few weeks later, the actual administration of the federally-delivered COVID-19 vaccines was the responsibility of the states, with some states handling the administration of the vaccines much better than others:

Some six weeks after the first shipments, the U.S. has administered some 53% of distributed vaccines. The gap continues to grow between states that are getting shots into arms, and those arguing over who gets what and when. North Dakota had administered some 84% of its supply as of Jan. 23, and West Virginia about 83%—far better than states like California (45%) or Alabama (47%). Federalism is showing what works—and what doesn’t. The federal government’s main role is the production and distribution of vaccine doses, and the Biden Administration is fortunate to inherit Operation Warp Speed. Mr. Biden says he’ll trigger the Defense Production Act to expand vaccine production, albeit without details on how he’d build on the existing plan … [V]accine administration was always intended to be state-led, and too many jurisdictions squandered the ample time they had for preparation … [T]he biggest state mistakes so far have been adhering too much to the federal government’s initial guidance to limit the first batches to health-care workers and long-term care residents, followed by front-line employees and those over age 75. States couldn’t find enough takers, and precious doses ended up in the trash. The most successful state rollouts have departed from overly prescriptive federal rules. North Dakota stuck with the initial recommendations on health-care workers and nursing-care residents, but then threw open its program to anyone age 65 and up, as well as to adults with underlying health risks. South Dakota added law enforcement and corrections staff to its initial tiers, and then also moved quickly to inoculate 65-and-older adults and school workers. The states with the highest per capita vaccination rates are all rule-breakers—Alaska (12,885 per 100,000), West Virginia (11,321), and North Dakota (9,602) as of Jan. 23 … Mr. Biden is under pressure from the left to infuse the vaccine rollout with “equity” politics. As California (5,568 per 100,000) and New York (5,816 per 100,000) show, such bickering is a recipe for fewer vaccines and more deaths. States are proving again that they can show a better way than orders from Washington.

Initially, many states imposed complicated formulas on who could get the vaccine first when it had always been the very old who were most at risk. As Paul Peterson has wrote in January, 2021:

To deliver free vaccines with maximum speed, the health-care system needs to follow a simple rule that applies to everyone. Fortunately, such a rule is readily available: date of birth. The older the person, the higher the priority. One can prove one’s age simply by showing a driver’s license, Medicare or Medicaid card, or another form of identification. For most, that information is already embedded in the files of hospitals, pharmacies and doctors’ offices.

As Arthur Herman, best-selling author of “Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II,” wrote in the Wall Street Journal in February, 2021:

In the U.S. federal system, however, state governments can’t be steamrolled by Washington. The Arsenal of Democracy was able to ship its goods to two all-powerful federal agencies, the War and Navy departments, which knew how to get those weapons to the soldiers, sailors and airmen who would use them. There’s no corresponding federal agency in this case. About 50 million vaccination doses have been made and shipped, but only half have been administered, while fewer than six million people have received second doses. While some states have dealt with the crisis well, many have found the process of getting shots into arms overwhelming.

As the Wall Street Journal reported in March, 2021:

Critics scoffed when President Trump set a target of having a vaccine approved by the end of 2020, and Kamala Harris suggested she might not take a shot recommended by the Trump Administration. The Biden-Harris Administration has now changed to full-throated encouragement—though not before continuing to trash the Trump efforts. White House aides have suggested that they inherited little vaccine supply and no plan for distribution. Both claims are false. The supply was ramping up fast, and while there were distribution glitches at first, the real problem has been the last mile of distribution controlled by states. Governors like New York’s Andrew Cuomo tried to satisfy political constituencies that wanted early access to vaccines, adding complexity and bureaucracy that confused the public. Mr. Biden made the same mistake Tuesday, asking states to give priority to educators (read: teachers unions), school staffers and child-care workers. That is arbitrary and unfair. A 30-year-old teacher who may still work remotely until September is at far less risk than a 50-year-old FedEx driver who interacts with customers all day. The fairest, least political distribution standard is age. The Trump Administration’s Operation Warp Speed also contracted most of the vaccine supply for production before approval by the FDA: 200 million doses each of Pfizer and Moderna, and 100 million of J&J. No one knew which technology would be approved first, if at all, so the government wisely bet on several. This was the best money the feds spent in the pandemic. Mr. Biden ought to give the vaccine credit where it is due—to U.S. drug companies and Operation Warp Speed.

And as Scott Atlas has pointed out, “Under Operation Warp Speed, the federal government took nearly all the risk away from private pharmaceutical companies and delivered highly effective vaccines, hitting all promised timelines.” A major reason the federal government “took nearly all the risk away from private pharmaceutical companies,” thereby allowing them to “deliver[] highly effective vaccines,” was the enactment, back in 2005, of a federal statute that largely protected vaccine manufacturers from frivolous lawsuits during the production and administration of pandemic vaccine, provided they followed all relevant federal rules and regulations. I discuss that and related federal legislation in a law review article I wrote in 2007, which can be found here and here. We’ll explore the many dysfunctions and disincentives created by the U.S. legal system in a future essay series, but I would just point out now that if those dysfunctions and disincentives hadn’t already been largely obviated by a federal statute applicable to the emergency distribution of vaccines during a pandemic, lawsuits challenging the process all along the way would have dramatically slowed vaccine development and administration.

This concludes this series of essays on trends in federal regulations.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5

Great stuff Paul!