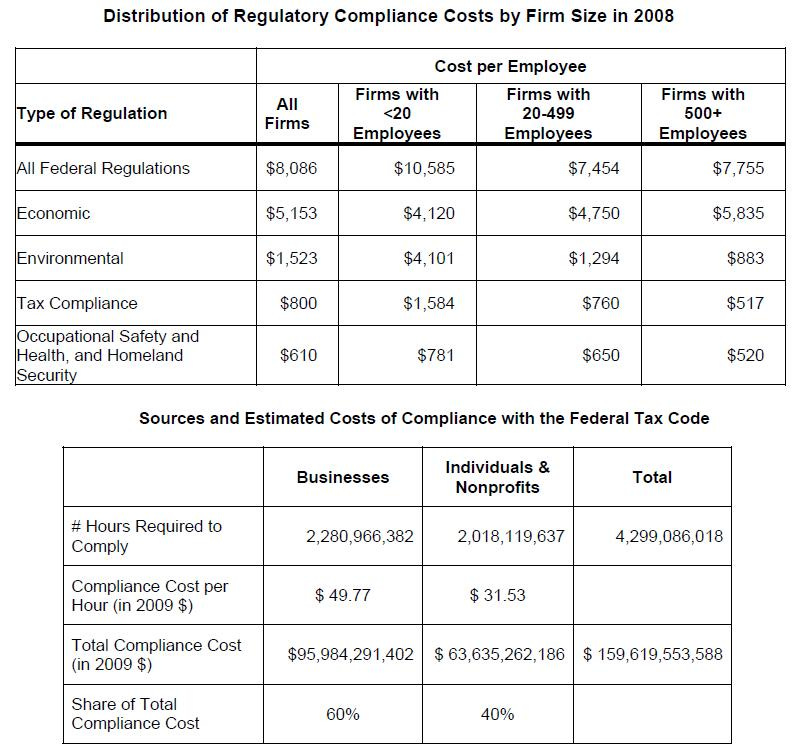

In 2012, the Small Business Administration assessed the regulatory and tax compliance costs to businesses this way, in terms of costs per employee and per hour spent, respectively.

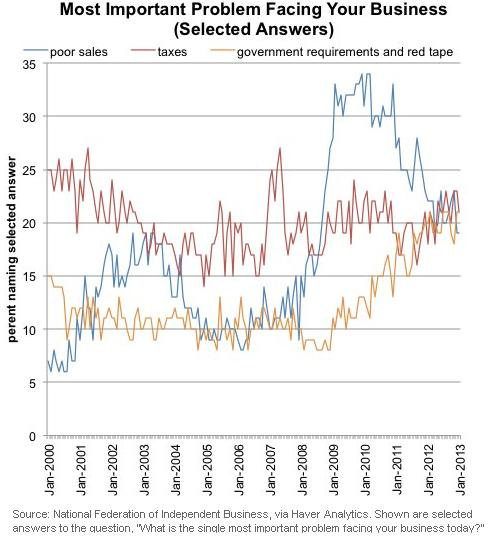

In previous years, surveys of small business owners showed a steady rise in the ranking of “government requirements and red tape” as a most important problem.

At the end of 2019, a national economic optimism index of small business owners, the Walls Fargo/Gallup Small Business Index, was at its highest level ever under the Trump Administration, up 162% since the final months of President Obama’s two terms.

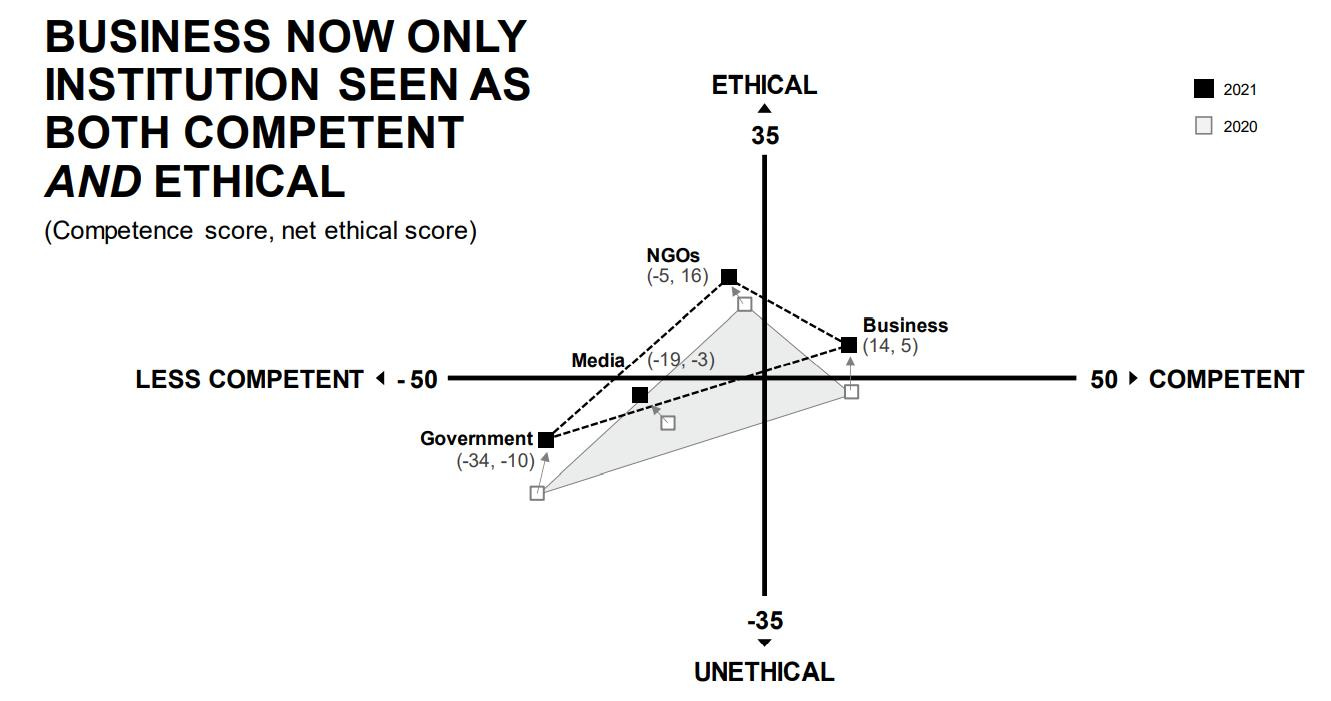

The Edelman Trust Barometer Global Report 2021 found that “Business is the only institution that is now perceived as being both ethical and competent enough to solve the world’s problems.”

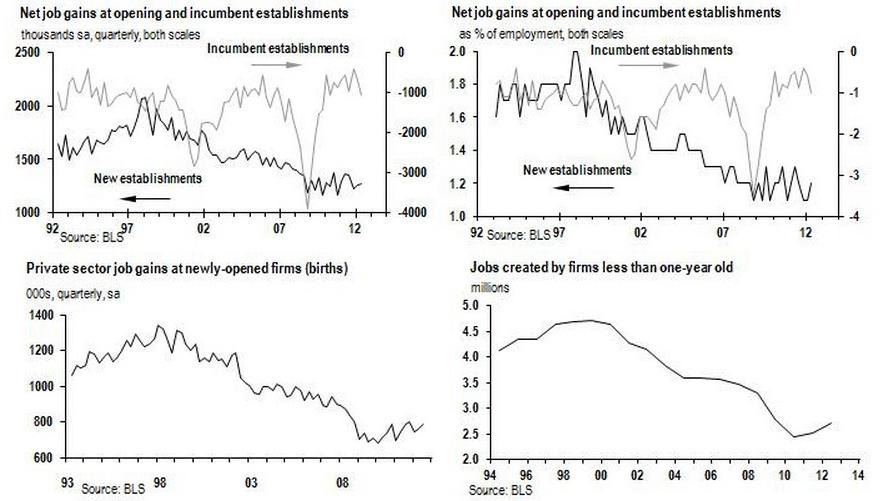

However, the growth in startup company employment has declined significantly over the last few decades.

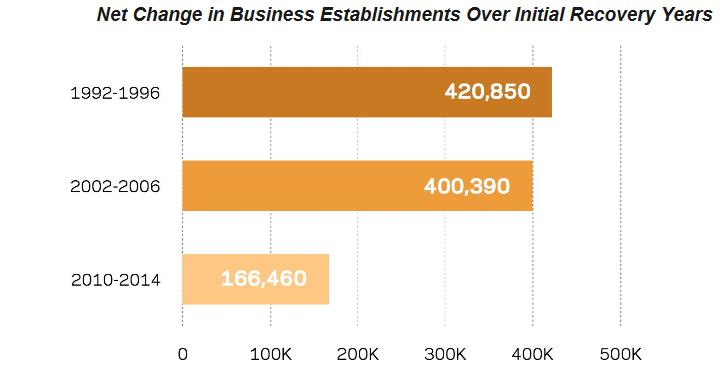

Compared to previous periods of recovery from economic recessions, the economy added significantly fewer new businesses after the latest recession (prior to the COVID pandemic).

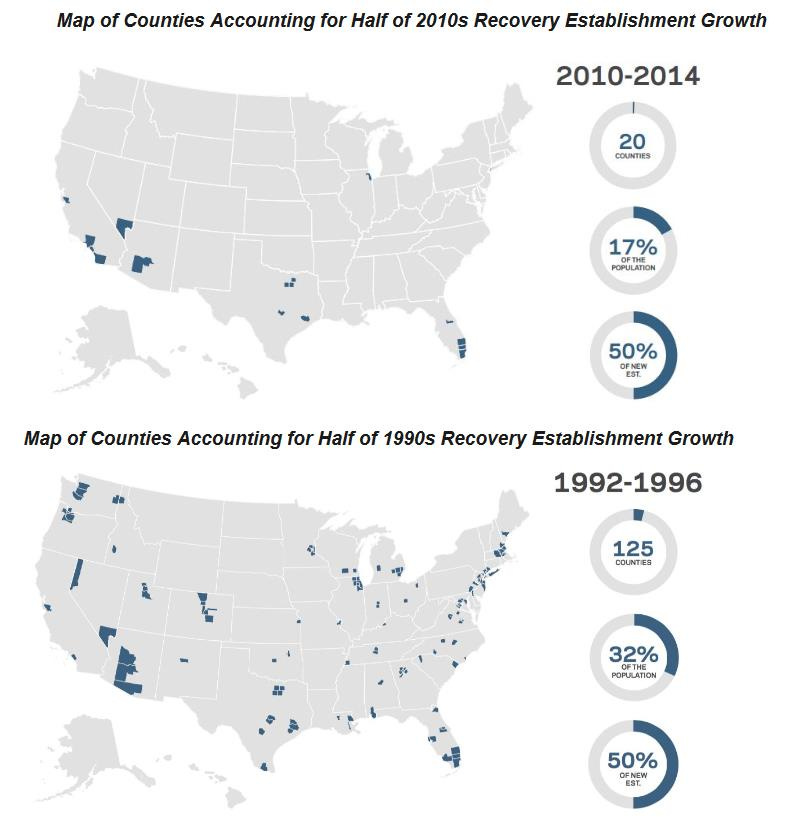

The geographic concentration of new business growth has also become startlingly insular over time.

Regulatory compliance costs are a major reason small companies have trouble succeeding. “In one year,” wrote Warren Meyer (the owner of a company who runs campgrounds) in 2015, “I literally spent more personal time on compliance with a single regulatory issue -- implementing increasingly detailed and draconian procedures so I could prove to the State of California that my employees were not working over their 30-minute lunch breaks -- than I did thinking about expanding the business or getting new contracts.” On a larger scale, considering the cumulative costs of regulations, a Mercatus Working Paper concludes that “Had regulation been held constant at [the lower] levels observed in 1980, our model predicts that the economy would have been nearly 25 percent larger by 2012 (i.e. regulatory growth since 1980 cost GDP $4 trillion in 2012, or about $13,000 per capita).”

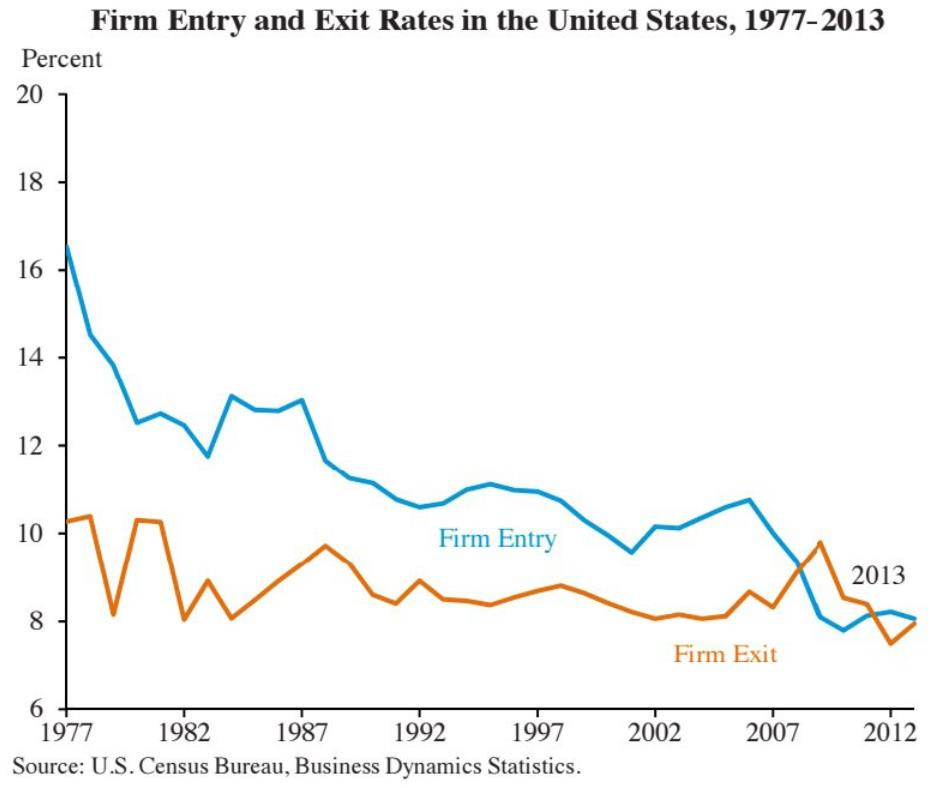

The U.S. economy has generally grown less dynamic over time as the firm entry rate (that is, firms less than one year old as a share of all firms) has declined. In 2016, and for the first time, firm exits exceeded firm entries.

In 2009, most foreign national students from Europe and China thought the best days of the U.S. economy were behind us, and most saw a country other than the U.S. as the likely location of their business startups.

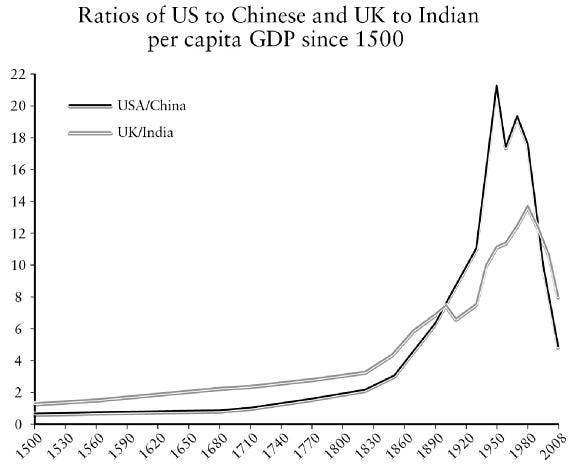

The relative decline of the United States, measured as a ratio of its gross domestic product compared to that of China, is a dramatic reversal of the trend first started in the U.S. in the 1800’s.

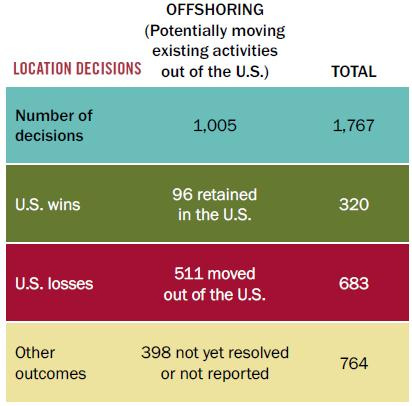

In a 2011 survey, Harvard Business School alumni were asked about 607 instances of decisions on whether or not to offshore operations. Of the reported results, the United States retained the business in just 96 cases and lost it in 511 cases.

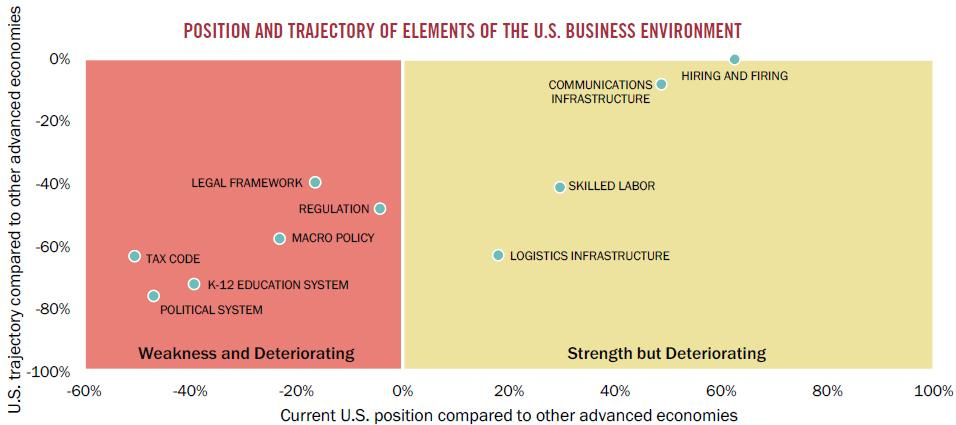

The chart below, from the same survey, shows (at the bottom left) that business leaders considered the legal framework, regulation, tax code, and K-12 education system in the United States to be a “weakness and deteriorating.”

Research also shows that the loss of jobs to overseas markets results in higher unemployment, lower labor force participation, and reduced wages, which in turn increases the use of transfer payments by those adversely affected.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at the regulatory drags on progress in science and medicine.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5