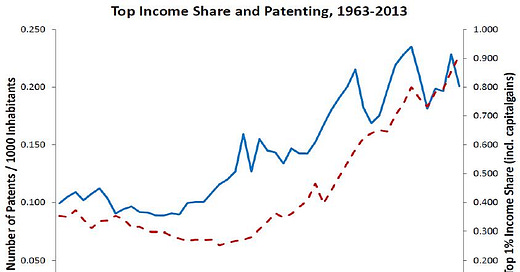

In the United States, the share of national income of those in the top 1 percent has grown since the 1980’s as proportionately more patents have been filed, indicating a link between innovation and income inequality.

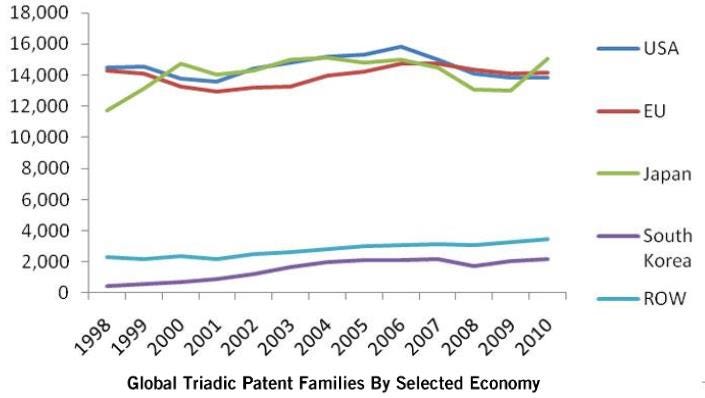

However, if one looks only at the more economically significant patents (so-called “triadic” patents that are filed in the United States, Europe, and Japan), the United States is creating 25 percent fewer such patents than it did in 1999.

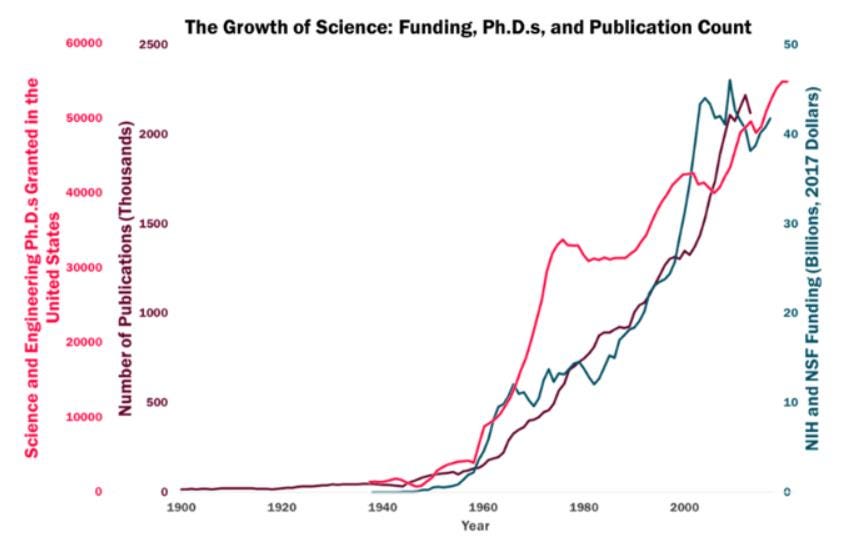

Today, there are more scientists, more funding for science, and more scientific papers published than ever before.

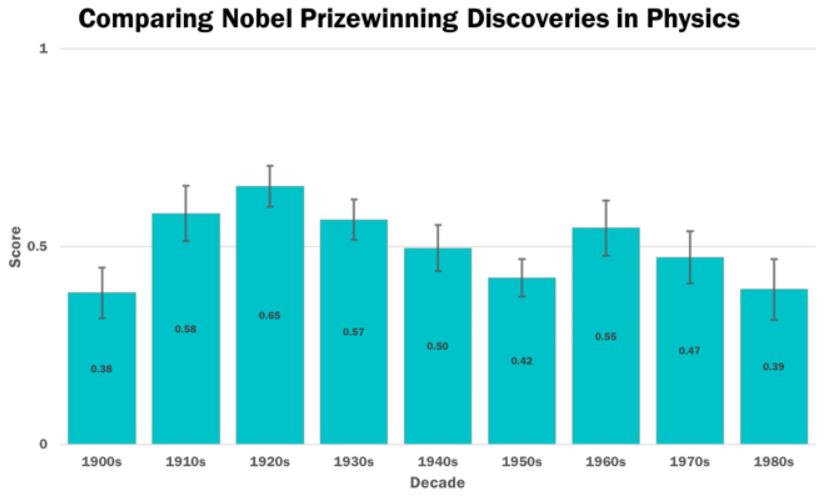

But a survey of scientists indicates that in more recent decades we are getting fewer scientific breakthroughs with lasting effects. (The graph stops at the end of the 1980’s because, in recent years, the Nobel Committee has preferred to award prizes for work done in the 1980’s and 1970’s, in part to help ensure the award goes to scientists whose work has stood the test of time. Just three discoveries made since 1990 have yet been awarded Nobel Prizes. The relatively fewer prizes since 1990 is also suggestive in that the 1990’s and 2000’s were the decades over which the Nobel Committee has most strongly preferred to skip back and award prizes for earlier work.)

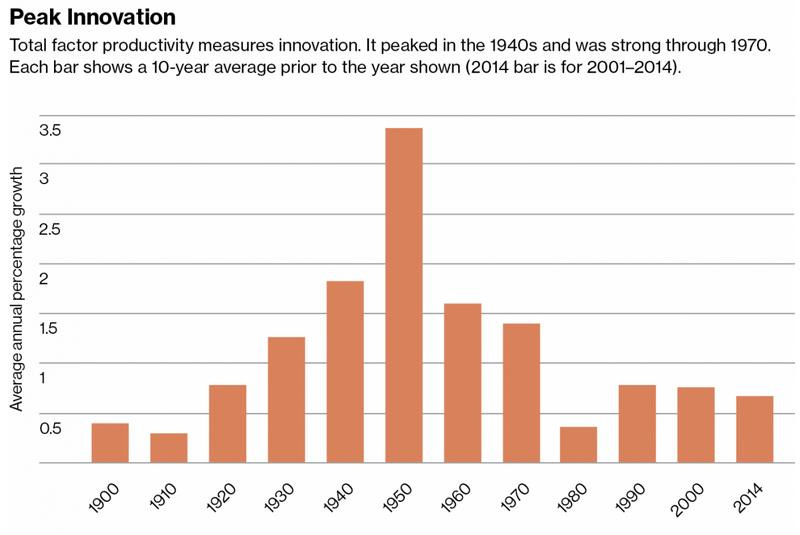

U.S. productivity-increasing innovations peaked prior to the rise of the regulatory state in the 1960’s.

As Tyler Cowen has pointed out:

Looking backwards, it’s striking how unevenly distributed progress has been in the past. In antiquity, the ancient Greeks were discoverers of everything from the arch bridge to the spherical earth. By 1100, the successful pursuit of new knowledge was probably most concentrated in parts of China and the Middle East. Along the cultural dimension, the artists of Renaissance Florence enriched the heritage of all humankind, and in the process created the masterworks that are still the lifeblood of the local economy. The late 18th and early 19th century saw a burst of progress in Northern England, with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. In each case, the discoveries that came to elevate standards of living for everyone arose in comparatively tiny geographic pockets of innovative effort. Present-day instances include places like Silicon Valley in software and Switzerland’s Basel region in life sciences. These kinds of examples show that there can be ecosystems that are better at generating progress than others, perhaps by orders of magnitude.

He continues elsewhere that more spending isn’t necessarily the answer, as “U.S. life expectancy is basically going up in linear fashion. But if you look at expenditures, we used to spend a few percentage points of GDP on healthcare, and now it’s about 18%. So we’ve gone up to 18%, and we’re not even boosting the rate.”

In 2021, the United States ranked third on the Global Index of Innovation (compiled by INSEAD and the World Intellectual Property Organization).

Regarding medical progress, the Affordable Care Act (the “Obamacare” law) encourages the consolidation of doctors into larger physician groups, where there is less medical innovation. Further, medical technology innovation is deterred in the United States by the comparative inefficiency of the medical device approval process in America, compared to the process in other European countries. (The 510(k) pathway refers to the approval process for low- to moderate- risk devices. The PMA pathway refers to the process for higher-risk devices.)

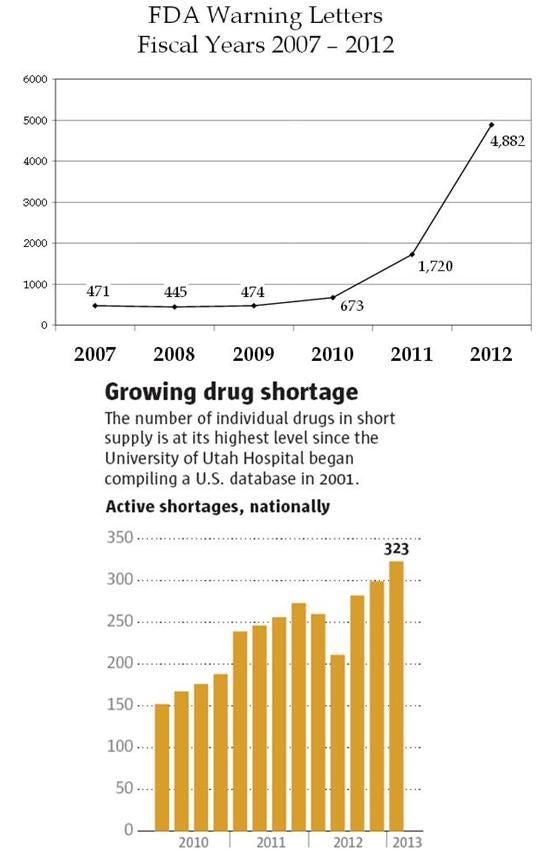

As the federal Food and Drug Administration has issued many more “warning letters” warning drug companies of federal regulations violations in recent years, an unprecedented shortage of crucial drugs has developed in America.

Vincent T. DeVita Jr., an oncologist who is a former director of the National Cancer Institute, a former director of the Yale Cancer Center, and a former physician in chief at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center has written: “I’d like to be able to say that as cancer drugs have become increasingly more complex and sophisticated, the F.D.A. has as well. But it has not.” In fact, he writes, “the rate-limiting step in eradicating cancer today is not the science but the regulatory environment we work in.”

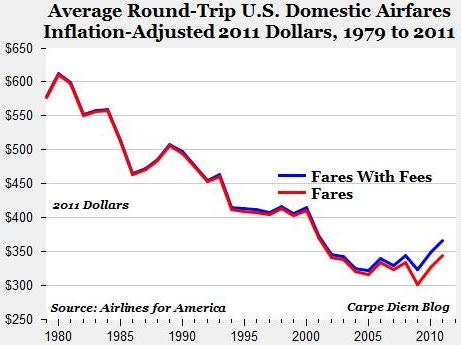

More regulations also mean higher prices generally. For example, since the once heavily-regulated airline industry was deregulated in the 1970’s, inflation-adjusted domestic airfare prices have fallen dramatically.

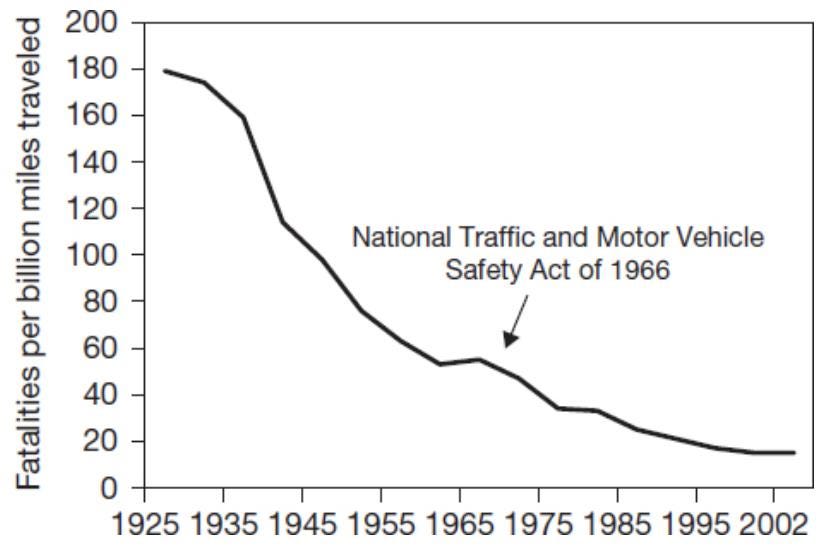

Greater risk-aversion by the consuming public, and not more regulations, are often the cause of better safety. Automobile fatalities have declined steadily since 1925, with the introduction of federal safety regulation showing only a minor effect.

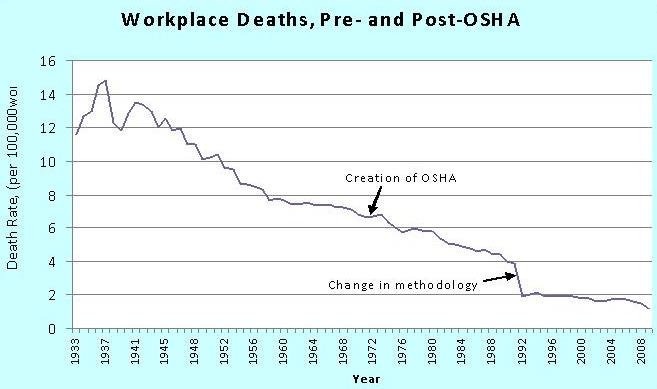

Similarly, workplace injuries have declined steadily over the years, with the creation of federal agency safety regulations showing only a minor effect.

Costly regulations that do little to increase safety raise prices for all consumers and disproportionately hurt the poor, who could better use the money to more greatly reduce risks to themselves by, for example, living in safer neighborhoods.

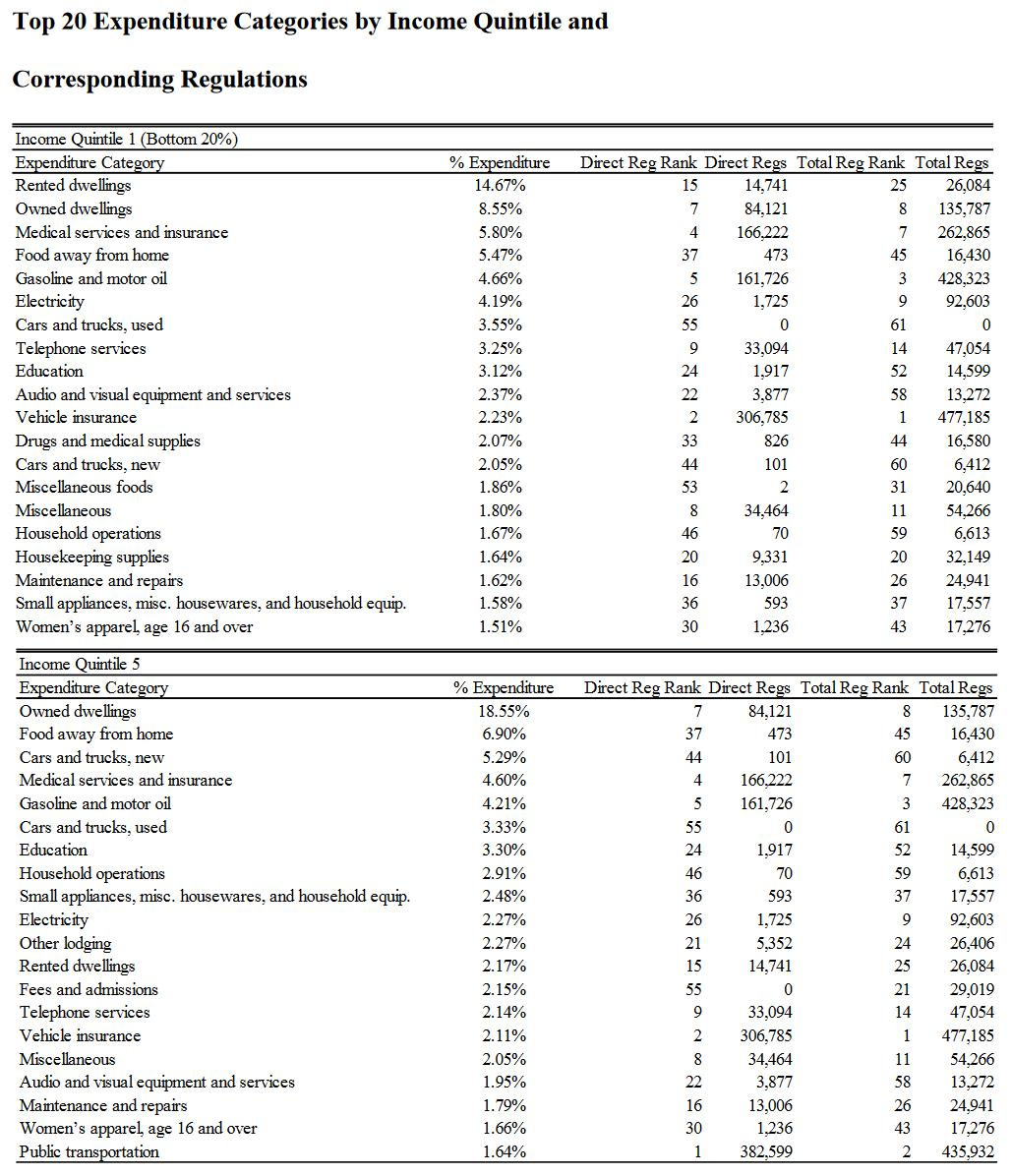

Researchers at the Mercatus Institute have found that federal regulations are more costly to those with lower incomes than those with higher incomes:

We document consumer spending patterns by income group and find that the lowest-income households spend a larger fraction of their income in areas that are more heavily regulated. The opposite is true of the wealthiest households; they allocate more of their spending to goods and services that are subject to fewer regulations. Our estimates of the effect of increased regulations on price levels suggest a positive and statistically significant relationship. A 10 percent increase in regulations is associated with a 0.687 percent increase in prices.” They point out that “Households from the lowest-income quintile spend more than five-and-a-half times as much on rented dwellings than households from the highest-income quintile, as a percentage of total expenditures. They spend almost 85 percent more on electricity as a percentage of total expenditures and 50 percent more on telephone service. Other areas where the poorest households spend a larger proportion of their income are drugs and medical supplies, medical insurance, and miscellaneous food items.

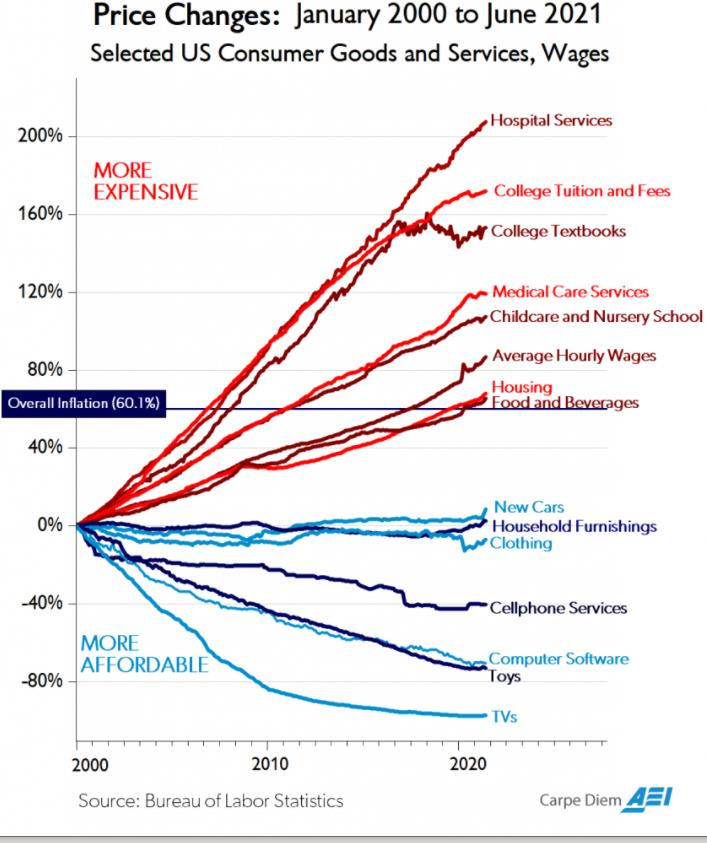

While the costs of things the federal government regulates and funds have soared, the costs of things the government generally does not so regulate and fund have declined.

Oddly, President Biden issued a memorandum on his first day in office that instructs the federal administrative agencies to “identify ways to modernize and improve the regulatory review process” that “fully accounts for regulatory benefits that are difficult or impossible to quantify.” With all the quantifiable evidence of the harm that excessive regulations does, the last thing we need is a federal effort to claim benefits from federal regulations that are “impossible to quantify,” so yet more regulations can be issued without even the pretense of evidentiary justifications.

In the next and final essay in this series, we’ll look at changes to the regulatory regime and their effects during the COVID pandemic.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5