Federal Regulatory Trends – Part 2

Federal regulations and regulators in historical and political context.

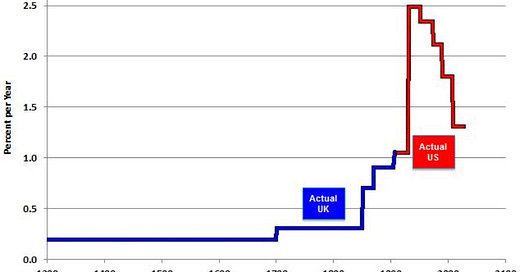

From 1300 until the greater development of property rights and commerce in the 1700’s, growth in the real gross domestic product per capita of each leading economic nation (which was the United Kingdom until 1906, at which point it became the United States) flat-lined at a very low level. Then it grew dramatically, until the 1960’s, when it began a continuous decline in the United States.

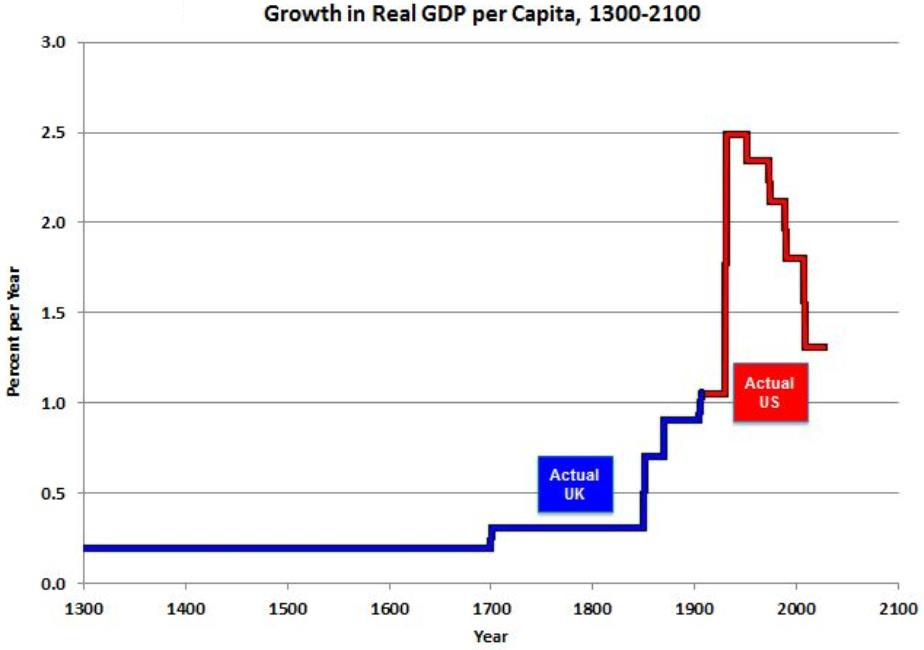

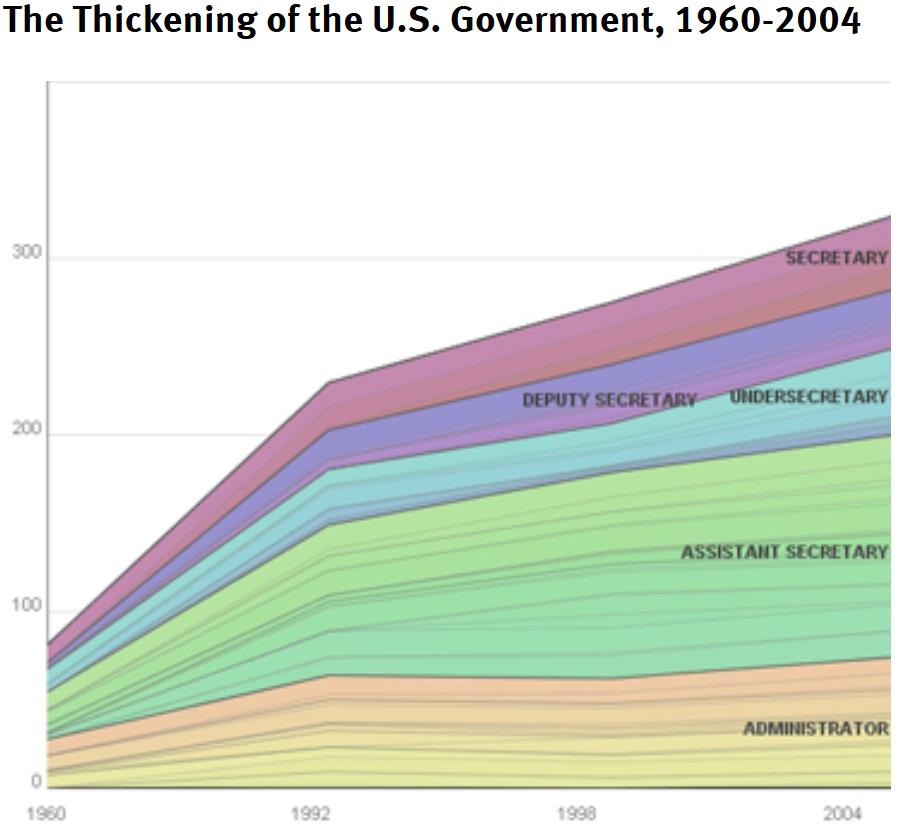

The following chart shows how the government has become involved in more and more areas over time, with the most dramatic expansions of involvement coming in the 1960’s.

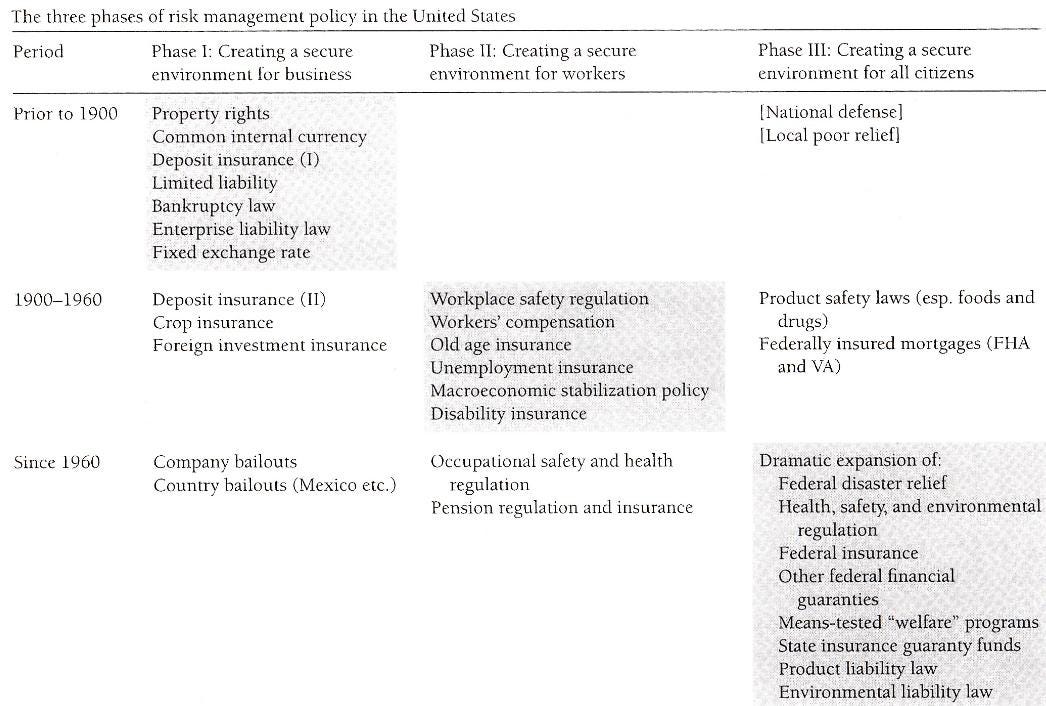

And as regulation have grown, they’ve created more so-called “moral hazards,” which are situations in which people need not take into account the full consequences of their actions because regulations hold other entities responsible.

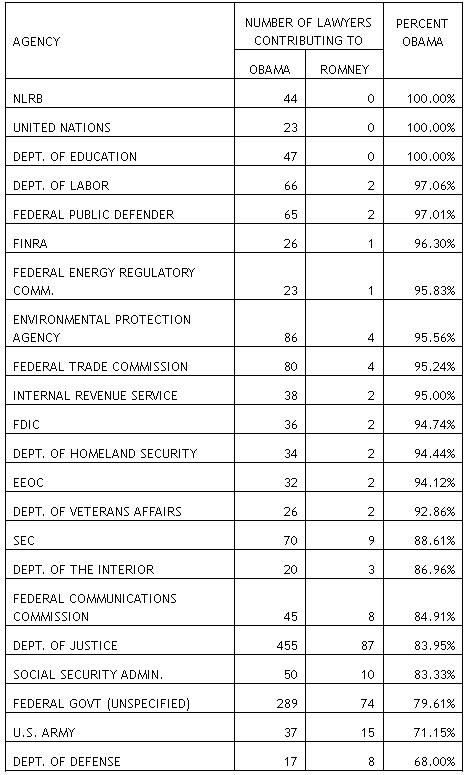

At the same time, the people who occupy regulatory positions contribute far disproportionately to the major political party that most supports increased government regulations. Lawyers in every federal government agency contributed overwhelmingly to President Obama compared to his presidential challenger Mitt Romney during the 2012 campaign. This table shows the results for all agencies with at least 20 employees who contributed to either the Obama or Romney campaigns.

Regarding the Department of Justice in particular (the federal agency charged with enforcing federal law), and the 2016 election cycle, as has been reported:

Political donations from those who work at the Department of Justice (DOJ) overwhelmingly favor Democratic candidates so far this cycle, data shows. Individuals at the DOJ have contributed a total of $192,534 so far this election cycle, with $159,800 (83 percent) of this amount going to Democrats. Republicans, on the other hand, have been the recipients of just 14 percent of the total contributions from those at the agency, pulling in $27,129 in donations. Throughout the 2016 election cycle, employees at the DOJ also overwhelmingly favored Democrats.

Similar results followed a more recent analysis.

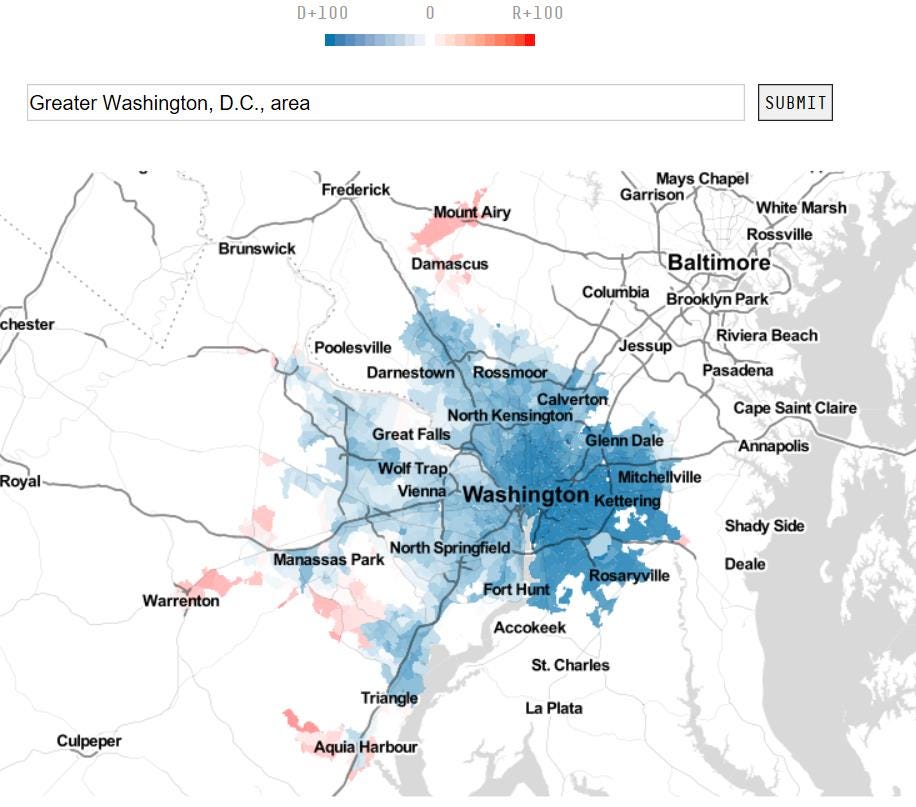

The federal government generally tends to be a more attractive employer to people who believe more government is better than less government. And so all the precincts in the Greater Washington, D.C. area are overwhelmingly Democratic.

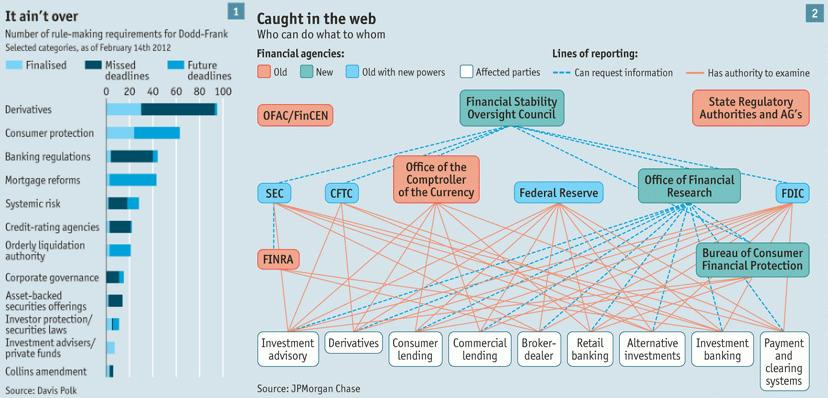

Often, regulations, far from alleviating the problems they purport to solve, make the situation worse. For example, the federal financial regulatory laws enacted following the financial crisis of 2008 created a complex new system of regulations, as illustrated by the chart below.

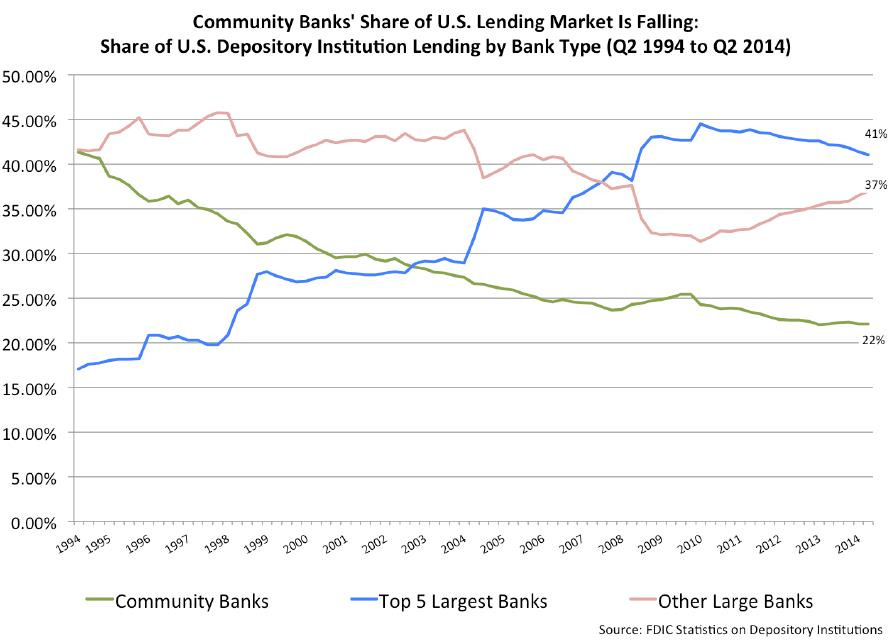

Those regulations, part of the federal Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, imposed disproportionately large regulatory burdens on small banks (community banks), which ended up resulting in greater, not reduced, concentration of big bank influence in the banking sector, according to researchers at the Harvard Kennedy School.

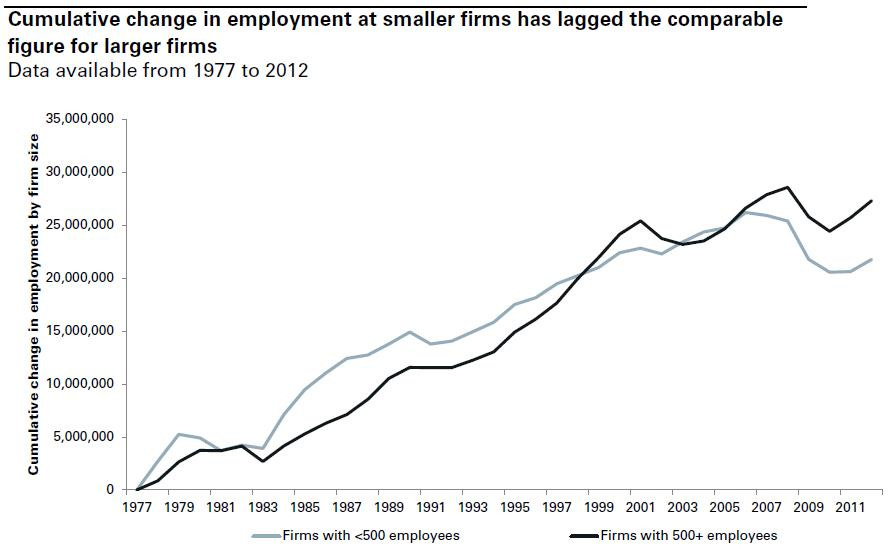

Large companies have access to credit in the capital markets because they are large enough to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission and finance themselves through the issuance of bonds, notes, and commercial paper. On the other hand, small businesses -- which constitute almost all 23 million small firms in the United States, including 5 million small-business employers -- are required to rely primarily on community banks for their credit needs, but now there are fewer community banks, limiting economic growth. In a Goldman Sachs report published in April 2015, the authors found that firms with more than 500 employees grew faster after 2010 -- the year of Dodd-Frank’s enactment -- than the best historical performance over the last four recoveries. These firms largely had access to the capital markets for credit. However, jobs at firms with fewer than 500 employees declined over this period, although this group had grown faster than the large-firm group in the last four recoveries.

Although 64 percent of net new jobs in the U.S. economy between 2002 and 2010 came from employment by small business, this source of growth largely disappeared after the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act. While larger firms have access to credit in the capital markets, millions of small firms, limited to borrowing from regulation-strained community banks, were not getting the credit they needed to grow and create jobs.

Regulatory costs generally are also a third higher for small businesses than for large companies.

In 2021, the Biden Administration’s Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) officially renounced any efforts to determine the impact on regulations on small businesses. As James Broughel writes in National Affairs:

In 2021, HHS repealed a rule enacted by the Trump administration that would have required the agency to periodically review its regulations for their impact on small businesses. The measure was known as the SUNSET rule because it would attach sunset provisions, or expiration dates, to department rules. If the agency failed to conduct a review, the regulation expired. Ironically, in proposing to rescind the SUNSET rule, HHS argued that it would be too time consuming and burdensome for the agency to review all of its regulations. Citing almost no academic work in support of its proposed repeal — a reflection of the anti-consequentialism that animates so much contemporary regulatory policy — the agency effectively asserted that assessing the real-world consequences of its existing rules was far less pressing an issue than addressing the perceived problems of the day (by, of course, issuing more regulations). Through its actions, HHS has rejected the very notion of having to review its own rules and assess whether they work.

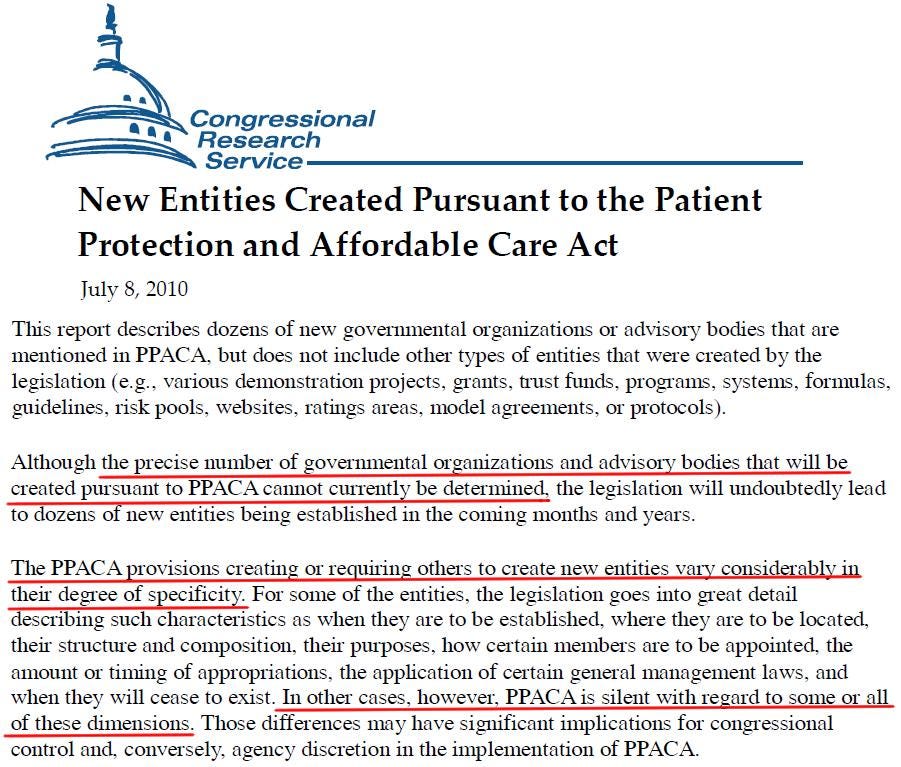

Regarding health care regulations, the number of new governmental organizations created by the Affordable Care Act could not even be determined by the Congressional Research Service.

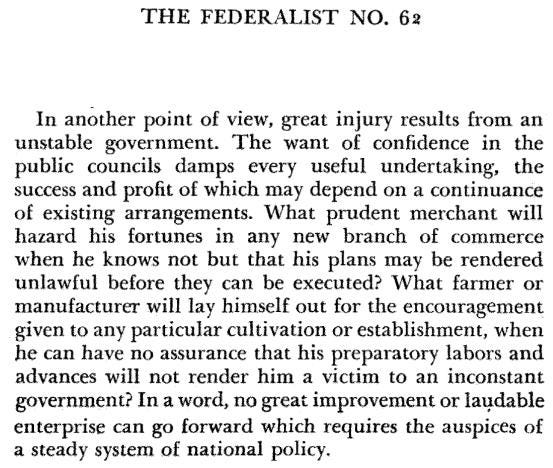

Such legal uncertainty was condemned by James Madison and Alexander Hamilton in their Federalist Papers, which they wrote in support of the ratification of the Constitution. Federalist Paper No. 62, states as follows:

As Madison also wrote in the same Federalist Paper No. 62:

It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is today, can guess what it will be tomorrow. Law is defined to be a rule of action; but how can that be a rule, which is little known, and less fixed?

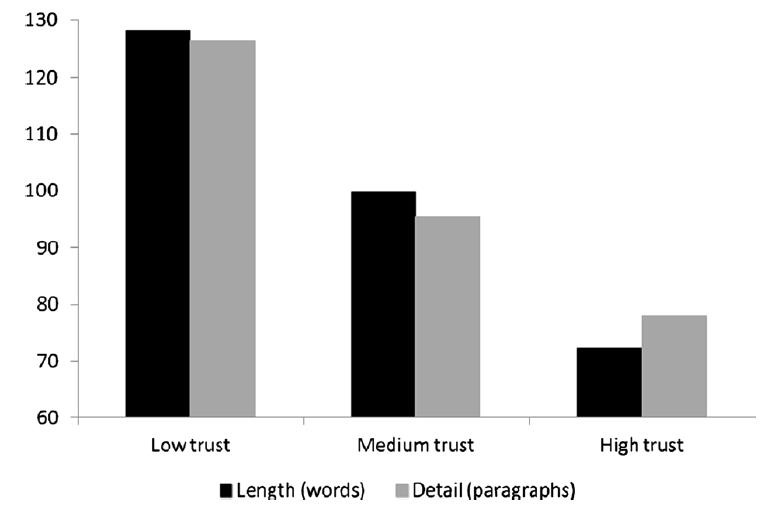

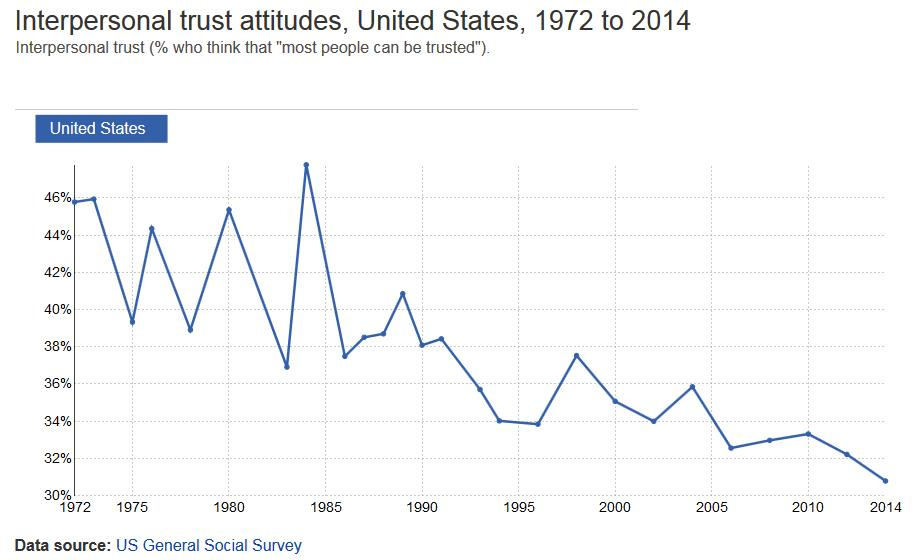

Researchers have shown that countries with constitutions that contain fewer words (such as the relatively concise Constitution of the United States) and are easier to understand tend to be countries in which there are high levels of social trust (that is, countries in which people tend to trust one another in cooperative efforts rather than relying on detailed, government-imposed rules).

Today, however, the United States is experiencing historically low levels of interpersonal trust, perhaps in part because its governing regulatory agencies have become so separated from the popular will, and added so dramatically to the complexity of government regulations without any clear popular consent.

Even the bureaucracy within the White House itself has grown dramatically, with the number of “Assistant Secretary,” “Undersecretary,” and “Deputy Secretary” positions greatly proliferating.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at the costs of regulatory compliance in America.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5