In previous essays, we looked at the vast influence the federal government and its bureaucracy has on America, down to the local level. In this series of essays, we’ll look at the precise nature, extent, and effects, of this federal bureaucracy.

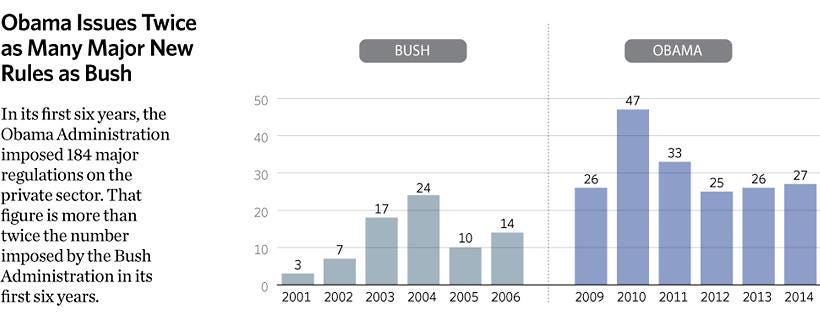

The increase in federal regulations ebbs and flows with presidential administrations of different political parties. The Obama Administration, in its first six years, promulgated twice as many major rules through federal agencies than the previous administration. (A “major rule” is defined as one that is likely to have an annual effect on the economy of $100 million or more.) President Obama is the only president in modern history whose time in office didn’t include at least one year of economic growth at the 3 percent historical average.

Since then, the growth of federal regulations was significantly slowed under the subsequent Trump Administration. As reported by Wayne Crews, “The December 31, 2019 Federal Register closed out with 2,964 final rules within its pages. This is the lowest count since records started being kept in the mid-1970s (that records began at the bicentennial is itself indicative of the disinclination to disclose). Trump’s earlier 2017 count of 3,281 had been the previous best ... It is a notable achievement that all three of the lowest-ever annual rule counts belong to Trump,” and “some of [President] Trump’s ‘rules’ are rules written to get rid of or replace other rules.”

The regulatory researchers at the American Action Forum, whose work is based on cost reports in agencies’ own regulatory impact analyses, found that on average the Trump administration imposed annual net regulatory costs of $10 billion, compared to $111 billion for the Obama administration and $43 billion for the George W. Bush administration. But as pointed out by researchers at the Brookings Institution, “But wiping existing regulations from the law books is considerably more difficult than declining to take new actions. Most deregulatory actions must go through the same procedures as regulatory actions, including a notice and comment process. Most crucially, agency final actions are generally subject to judicial review, and the majority of the Trump administration’s important deregulatory actions were litigated immediately.” Still, “While the Trump administration’s legal difficulties certainly limited the extent to which they were able to realize their deregulatory goals, it is also clear that in most matters they succeeded in significantly altering the status quo as of the end of the Obama administration.”

Once federal regulations are in place, it’s rare that they ever go away, and even rarer that a rule’s adopted that requires the withdrawal of previously-promulgated rules on a certain schedule. Federal rules that require the withdrawal of wasteful rules is important, because the way federal agencies operate makes it very expensive for parties harmed by its regulations to challenge them, and have them struck down, in court. As Professor Gary Lawson has written:

Consider the typical enforcement activities of a typical federal agency -- for example, of the Federal Trade Commission. The Commission promulgates substantive rules of conduct. The Commission then considers whether to authorize investigations into whether the Commission’s rules have been violated. If the Commission authorizes an investigation, the investigation is conducted by the Commission, which reports its findings to the Commission. If the Commission thinks that the Commission's findings warrant an enforcement action, the Commission issues a complaint. The Commission’s complaint that a Commission rule has been violated is then prosecuted by the Commission and adjudicated by the Commission. This Commission adjudication can either take place before the full Commission or before a semi-autonomous Commission administrative law judge. If the Commission chooses to adjudicate before an administrative law judge rather than before the Commission and the decision is adverse to the Commission, the Commission can appeal to the Commission. If the Commission ultimately finds a violation, then, and only then, the affected private party can appeal to an Article III court. But the agency decision, even before the bona fide Article III tribunal, possesses a very strong presumption of correctness on matters both of fact and of law.

Further, as Christopher DeMuth Sr. and Michael Greve have written, Congress has over time limited its own ability to halt regulatory overreach through the appropriations process by allowing regulatory agencies to use non-appropriated funds to keep running:

To an unprecedented extent, regulatory agencies have come to rely on non-appropriated funds for their ordinary operations. Many have become self-financing; some have become profit centers for wider executive exertions ... Consider the Customs and Immigration Services (CIS) which processes and adjudicates immigrant applications for green cards (lawful permanent resident status), workers permits, naturalization, and dozens of subsidiary classifications. Through a series of incremental steps culminating in the 2002 “homeland security” legislation following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Congress directed that CIS cover essentially its entire budget through application fees. This means, for example, that the $985 filing fee for a green card covers not only CIS’s review and processing costs but also a share of its activities that do not generate revenue, such as adjudication and asylum applications. CIS does not have a formal revolving fund (it has requested one), but retains its fee revenues in its own account and maintains the account over time to cover its entire budget (with minor exceptions) without congressional appropriations. The agency’s special status came to light in November 2014, in the wake of President Obama’s executive revision of statutory immigration policies that many in Congress opposed on constitutional or policy grounds or both. Shortly after the president announced his actions, opponents announced that they would countermand them with a rider to CIS’s appropriations for the coming year. A few days later came the embarrassed retraction: staffers had discovered that USCIS is self-funded and financially independent of Congress.

Similarly:

[T]he Telecommunications Act of 1996 authorizes the FCC to set and collect taxes for promoting ‘universal service’ and gives the Commission wide discretion to determine whom to tax and at what rate and how to spend the revenues. … [T]he CFPB, established by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, enjoys a different form of agency self-financing. The Bureau is funded by a draw (up to a statutory cap) from the revenues of the Federal Reserve System. The Fed’s revenues come from fees on private banks and earnings from open market operations; it covers its own operating budget (along with other expected expenses) from the bank fees and remits the remainder to the Treasury. The Bureau’s budget, like that of the Federal Reserve, is entirely independent of congressional appropriations, but is capped at 13 percent of the Fed’s operating budget.

These and many other federal agencies are consequently largely immune from Congress’ power to change policy through the appropriations process, absent statutory changes that restore that power to Congress, or the promulgation of federal rules that require certain previously-promulgated rules to be withdrawn.

During the response to COVID-19, President Trump issued an executive order, “Regulatory Relief to Support Economic Recovery,” which included a regulatory bill of rights that identifies “principles of fairness in administrative enforcement and adjudication” and requires agencies to revise their procedures accordingly. Some of the principles include the following: You should be presumed innocent unless proven guilty of violating a regulation. Agency enforcement should be prompt and fair, not needlessly drawn out. Disputes should be decided by neutral judges, not agency enforcement officials. Agency rules of evidence should be clear and fair, and agencies shouldn’t withhold evidence that is potentially exculpatory. Threatened penalties should be proportionate to the alleged wrong. Agencies shouldn’t coerce you into giving up your rights. Agencies shouldn’t engage in practices that cause unfair surprise. And agency practice should promote, rather than evade, accountability.

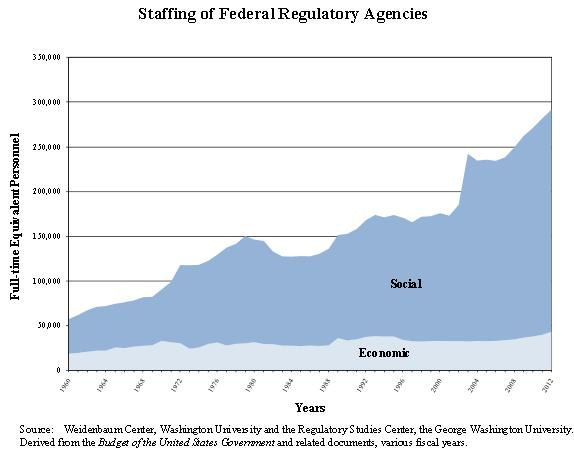

Since the 1960’s, the portion of the federal budget dedicated to federal regulatory agencies, and their staffing levels, has grown dramatically.

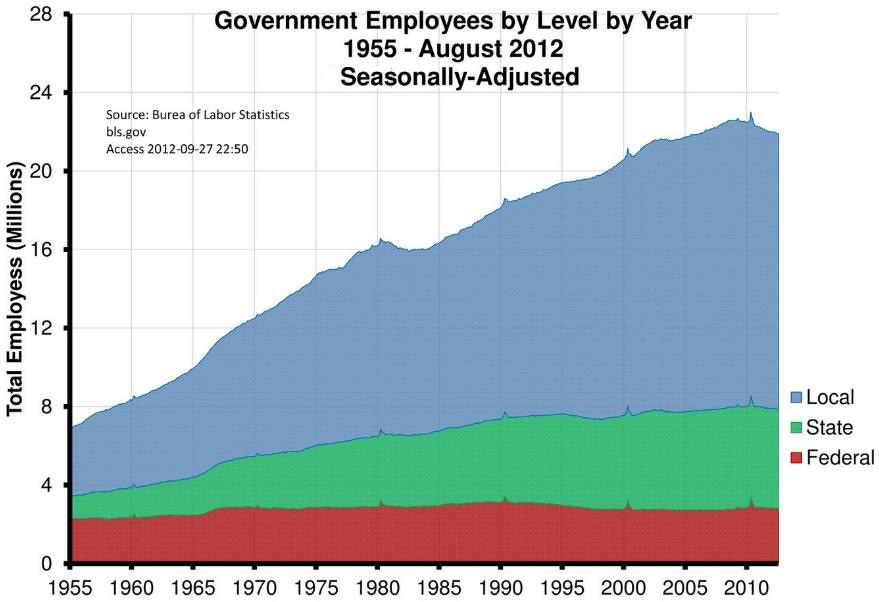

As was mentioned in a previous essay, while there hasn’t been much growth in federal government employees over the last many decades, given population increases, there has been a dramatic growth in the number of state, and especially local, government employees, who have increasingly come to administer federal programs by proxy in cooperation with federal government employees.

Not only does Congress delegate vast swaths of lawmaking power to federal agencies, but there has been a great rise in additional ways Congress, the President, and federal agencies have deviated from the traditional process of lawmaking, thereby diffusing responsibility for policies in complicated ways few people can even begin to understand.

These unorthodox practices result in many dysfunctions, as itemized in the chart below.

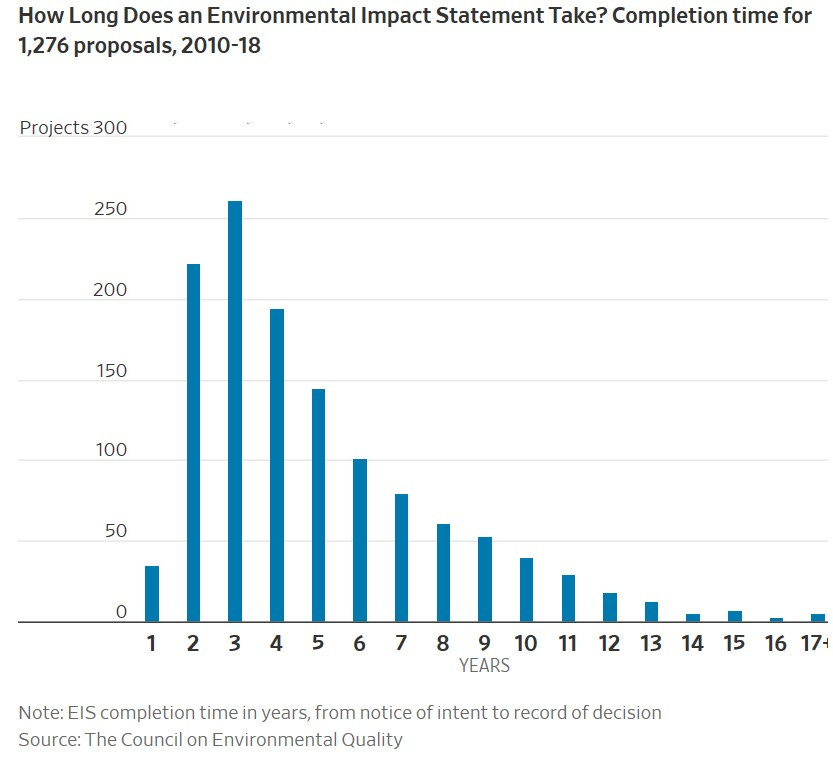

This gigantic flow chart shows the huge array of regulatory and bureaucratic requirements that must be met before any federally-funded highway project can proceed, helping to explain the poor state of America’s infrastructure. The Trump Administration’s efforts to reform this system received high praise from the Obama Administration’s “regulation czar,” Cass Sunstein. A variety of federal regulations also make building transportation infrastructure to rural areas much more difficult today, including environmental reviews that can cause the approval process for some projects to extend ten to fifteen years. A recent study concluded that a typical six-year delay in starting construction on public projects costs the nation over $3.7 trillion, including the costs of prolonged inefficiencies and unnecessary pollution during the period of legal review, more than double the $1.7 trillion needed through the end of this decade to modernize America’s infrastructure. The Trump Administration, in January, 2020, implemented regulatory changes to significantly streamline infrastructure projects.

As the Wall Street Journal stated in July, 2020, “In recent years the average review involving an environmental impact statement took 4.5 years, and the final document ran to 661 pages, before appendixes. In a quarter of cases, the process burned at least six years and 748 pages. Those timelines don’t necessarily count any subsequent lawsuits over whether the NEPA [the National Environmental Policy Act] review was faulty. One sadly spectacular outlier was a 12-mile highway expansion in Denver that took 13 years to get through environmental review.”

There is of course great public support for infrastructure improvements in America, but as Professor Joseph Hamburger has noted, as more people have become able vote, federal officials have sought ways of imposing rules though federal agencies that bypass the will of voters. He writes: “Administrative power tend[s] to expand in the wake of … [expanding] suffrage,” in that, following expansions of the voting franchise throughout modern history, there have been notable expansions in the administrative state under which the desires of voting Americans can be avoided through the imposition of laws through administrative agencies instead of elected representatives.

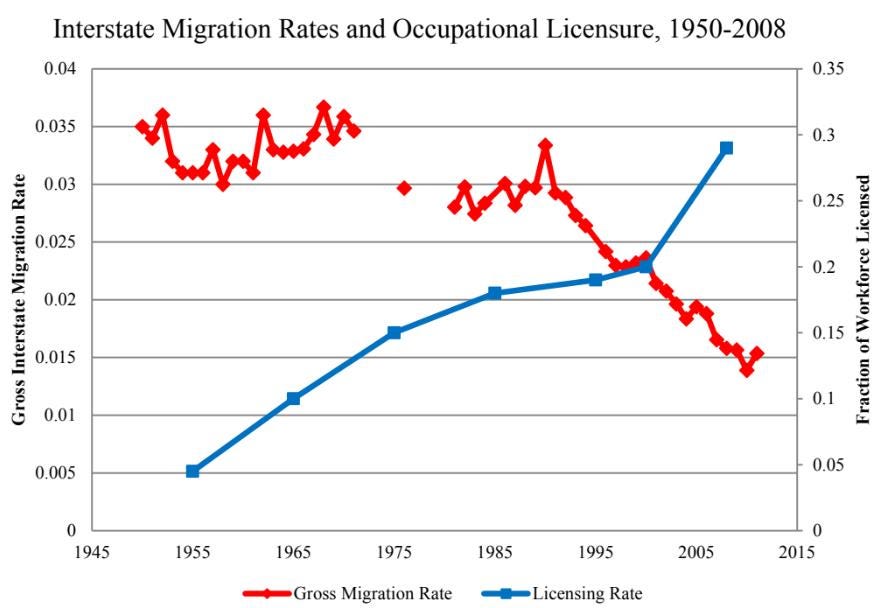

Regulations have also increasingly deterred people from entering top professions. Among the states, the percentage of jobs subject to professional licensing requirements has increased steadily, even though studies show licensing requirements generally restrict the supply of providers (including teachers) and raise prices without increasing provider quality.

Other researchers have found that “Individuals in licensed occupations with state-specific exam requirements move at a 31 percent lower rate between states than those with national exams,” with state test requirements’ especially reducing the mobility of teachers.

That’s because if someone has spent lots of time and money to obtain a license to work in that occupation from one state, they are reluctant to have to expend that time and effort all over again in another state, even if job prospects are better in another state. As a result, state licensing requirements reduce social mobility by deterring those in state-licensed professions from moving to other states (where their licenses might not be valid).

A comprehensive review of state licensing requirements can be found here.

Licensing requirements also contribute significantly to income inequality by artificially limiting the number of people who can join the ranks of the “top one percent,” which is dominated by people in licensed occupations. As one Brookings Institution study showed:

For lawyers, doctors, and dentists -- three of the most over-represented occupations in the top 1% -- state-level lobbying from professional associations has blocked efforts to expand the supply of qualified workers who could do many of the ‘professional’ job tasks for less pay. Here are three illustrations: The most common legal functions -- including document preparation -- could be performed by licensed legal technicians rather than lawyers, as the Washington State Supreme Court decided in 2012. These workers could perform most lawyer-like tasks for roughly half the cost. Unsurprisingly, legal groups opposed it … Proportion of lawyers in the top 1%? 15%. Many states allow nurse practitioners to independently provide general and family medical services, freeing up physicians to provide more specialized services. But most larger states do not. Again, typical nurse practitioner salaries are roughly half those of general practitioners with an MD. But, of course, physician lobbies stridently oppose the idea. Proportion of physicians and surgeons in the top 1%? 31%. Dental hygienists can perform many of the functions of more far expensive dentists, but regulations vary by state and in all but a few states, it is not possible for hygienists to own and operate their own practice. My analysis shows that just 2% of hygienists are self-employed compared to 63% of dentists. Proportion of dentists in the top 1%? 21%.

According to the Senior Economist at Gallup, “Almost all of the growth in top American earners has come from just three economic sectors: professional services, finance and insurance, and health care, groups that tend to benefit from regulatory barriers that shelter them from competition.”

A professor at Yale Law School has further pointed out that

Land-use laws and occupational licensing regimes limit entry into local and state labor markets; differing eligibility standards for public benefits, public employee pension policies, homeownership subsidies, state and local tax regimes, and even basic property law rules reduce exit from states and cities with less opportunity; and building codes, mobile home bans, federal location-based subsidies, legal constraints on knocking down houses and the problematic structure of Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy all limit the capacity of failing cities to “shrink” gracefully, directly reducing exit among some populations and increasing the economic and social costs of entry limits elsewhere.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at federal regulations and regulators in historical context.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5