In a previous essay series, we looked at the psychological concept of “locus of control,” and the evidence that people who have an “internal” locus of control (that is, people who see themselves primarily as in control of their own lives) are more successful on a variety of metrics than those with an “external” locus of control (that is, people who see themselves primarily as at the mercy of external forces beyond their control). In this essay, we’ll look at the related concept of “agency,” and why it should be taught.

Ian Rowe, in his book Agency, writes:

In October 2021, the Archbridge Institute think tank released an eye-catching report on existential agency showing that only 39 percent of American adults under age twenty-five think they have the power to live a meaningful life. Compare this to the 63 percent of all American adults who think so. This is despite the fact that young people are traditionally more idealistic and energetic than their elders and have their whole life ahead of them … This is … despite the fact that social, scientific, and technological progress has given the rising generation greater access to knowledge and more opportunities. Moreover, Archbridge Institute’s senior research fellow Clay Routledge, who authored the study, points out that these findings align with other research showing that young adults are increasingly anxious and afraid … Albert Bandura was one of the first psychologists to argue that a sense of personal efficacy forms the foundation of self-determination … [He wrote] “Unless people believe they can produce desired effects by their actions, they have little incentive to act, or to persevere in the face of difficulties. Whatever other factors serve as guides and motivators, they are rooted in the core belief that one has the power to effect changes by one’s actions.”

Developing the confidence that comes with knowing you control your own life in significant ways isn’t innate. It must be taught. As Rowe writes:

[P]ure self-reliance is a myth. Individuals do not develop such dogged self-determination until someone or some institution first helps them grasp that their effort is integral to achieving that goal. It is this core conviction that allows them to endure as they encounter barriers along the way.

Yet too many school leaders today, including our local school superintendent, discount accountability for bad behavior. Recall from the first essay in this series that, in response to the question “What is being done to hold students accountable who engage in very violent behavior?” she replied (at the 55:05 minute mark):

[W]e just have to be mindful when we use the word violence because we are talking about students who have experienced challenges, who’ve returned to school, and maybe their families are in crisis. There are a number of things that often go on as to why children may have behaviors or experience challenges in school. So I just want us to be mindful when we use that word violence because it’s a very harsh word and it’s a very emotional word because we want what’s best for all of our students.

That wasn’t the message delivered by President Obama in 2013, when he said “We all share a responsibility to move this country closer to our founding vision that no matter who you are, or where you come from, here in America, you can decide your own destiny. You can succeed if you work hard and fulfill your responsibilities.” And as Rowe writes:

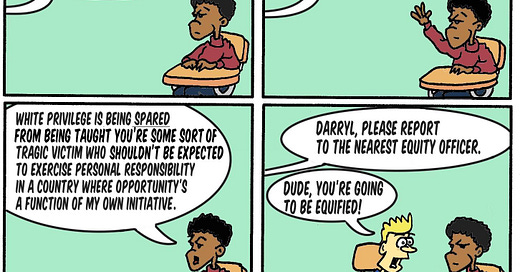

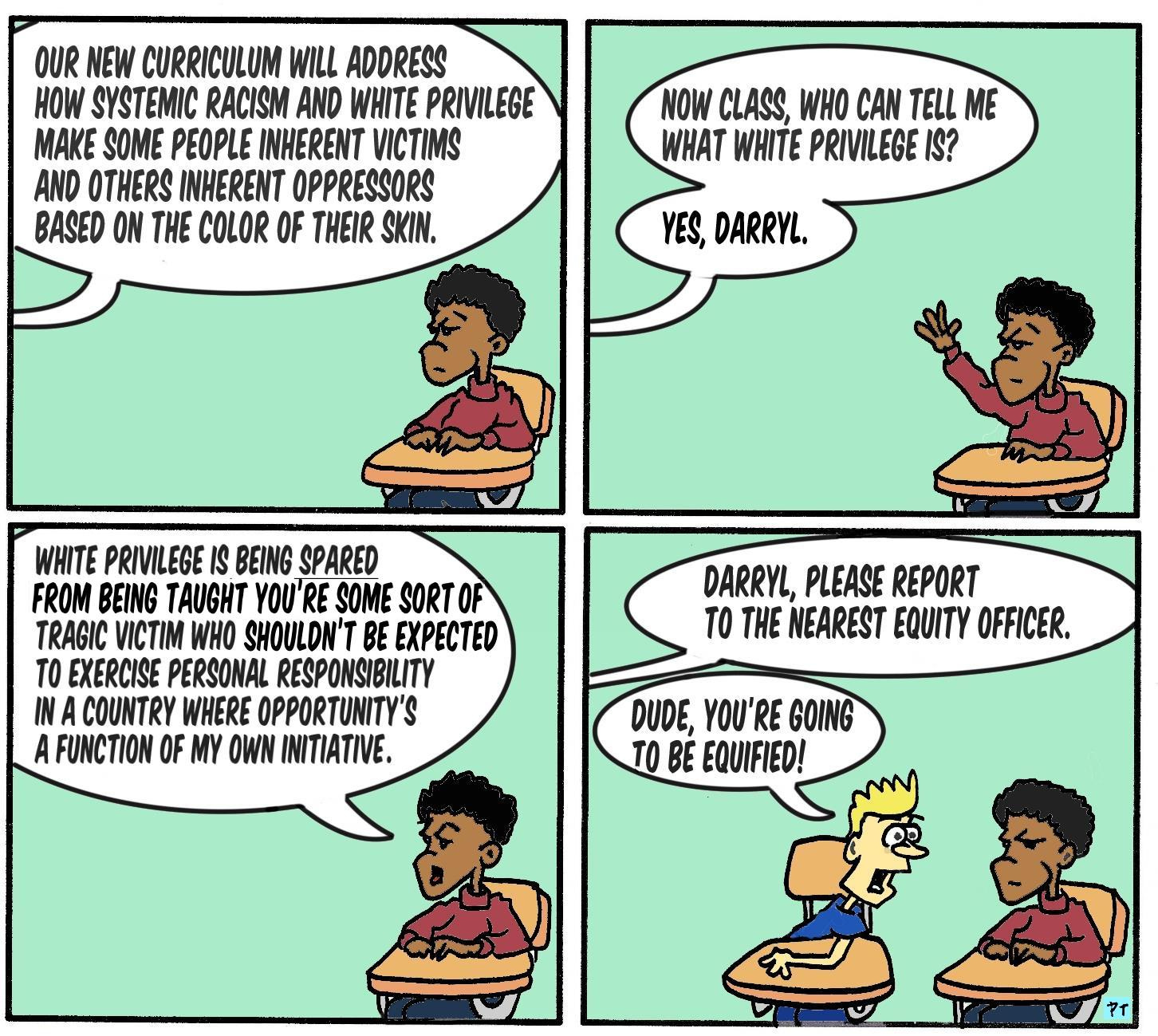

As an educator, when I hear the collective messages that emphasize grievance and dependency, I think of their corrosive impact on the primarily low-income, black and brown children who attend the schools I lead. This negative worldview can convince otherwise able kids that they are trapped in a lower caste of society and there’s simply nothing they can do -- they are powerless -- in the face of this rigid, discriminatory systemic structure. It can turn them into victims. Whether intentional or not, this debilitating ideology will have a psychological impact on kids.

Recall from the previous essay in this series that renowned defense lawyer Clarence Darrow argued that his client Leopold should have been spared the death penalty for his murder of another child because the blame lied instead with a system that introduced Leopold to the works of philosopher Friedericc Nietzsche, and his theory of the “superman,” a person who consciously created his own norms and rejected those of society at large. As Darrow argued:

I have just made a few short extracts from Nietzsche, that show the things that Nathan read and which no doubt influenced him. These extracts are short and taken almost at random. It is not how this would affect you. It is not how it would affect me. The question is how it did affect the impressionable, visionary, dreamy mind of a boy … Nietzsche held a contemptuous, scornful attitude to all those things which the young are taught as important in life; a fixing of new values which are not the values by which any normal child has ever yet been reared … [T]he superman was a creation of Nietzsche, but it has permeated every college and university in the civilized world.

Darrow argued that thinkers revered in elite circles sometimes have ideas that challenge certain norms of society. Today, of course, thinkers revered in elite circles, with best-selling books — such as Robin DiAngelo, Ibram X. Kendi, and Nikole Hannah Jones of the 1619 Project — explicitly reject the norm of a “colorblind” society in which, as Martin Luther King, Jr. said, people are judged not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. Instead, DiAngelo, Kendi, and Jones espouse norms that focus explicitly on race, and treat people differently based on race in order to somehow make up for current racial disparities they claim (falsely) are wholly or primarily caused by racism. But while many people are old enough to have seen the progress ushered in by Martin Luther King Jr.’s moral vision of a colorblind society, younger people without that experience are more open to the idea that everything should be viewed “through a racial lens,” and act accordingly. As Darrow said of Loeb:

Here is a boy at sixteen or seventeen becoming obsessed with these doctrines … He believed in a [Nietzschean] superman. He and Dickie Loeb were the supermen … Many of us read this philosophy but know that it has no actual application to life; but not he. It became a part of his being. It was his philosophy. He lived it and practiced it …

Today, many adults, too, and even school boards, not only read DiAngelo, Kendi, and Jones, but they actually do think their racialist worldview has beneficial applications to life, going so far as to enact school board policies based on the notion that educational benefits should be allocated strictly based on racial demographics, regardless of individual student performance. As Jonathan Haidt, author of the Coddling of the American Mind, points out (at the 31:08 minute mark), “The late Twentieth Century was actually a time of incredible moral progress. And on point after point, it’s reversing.” He gives examples of things that represent moral progress and explains how we’ve lost them in many ways today, including concepts like “equality before the law” (which is the antithesis of equality of outcomes).

As Rowe explains, focusing on equality of outcome based on racial demographics, rather than judging each student individually, locks in a race to the bottom:

Consider this data on reading proficiency from the 2013 National Assessment for Educational Progress as a way to understand the implications of today’s overemphasis on equity. On the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) exam in West Virginia, according to the Schott Foundation’s Black Boys Report, the percentage of black male eighth graders reading at NAEP proficient levels was 18.7 percent. Meanwhile, the white male eighth graders’ rate was 19.7 percent. What kind of Pyrrhic victory would it be if we closed that whopping one percentage point achievement gap? Yes, equity would be achieved—but a tragedy would remain. Less than one in five black and white eighth-grade boys would be reading at proficiency. White and black young men would be tied in a race to the bottom. Would this be cause for celebration? … Parents across America need to fully understand what is at stake when the contagion of antiracism or racial equity infects their school and what it means for their child’s pursuit of agency. The pursuit of racial equity is far more likely to result in lowered standards, division, and mediocrity and worse for kids of all races. Achieving racial equity typically means one of two outcomes: (1) black students must equal the performance of white students, or (2) black success equals the percent representation in the population. Either formulation places a ceiling on possibilities for black students. Why would we do that? Why would we adopt purportedly antiracist agendas that actually plant the seeds of white superiority and black inferiority instead of eliminating them?

When you fail to focus on agency by instead focusing on equality of outcome based on racial demographics, you fail to focus on individual achievement, which is the key to educational success. When even local school boards are backsliding and focusing on equality of outcome, not equality before the law, who could blame younger people for rejecting Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision of a colorblind society and instead embracing treating people differently based on the color of their skin? As Darrow said of his young client Leopold, who was charged with murder:

If this boy is to blame for this, where did he get if? Is there any blame attached because somebody [else] took Nietzsche's philosophy seriously and fashioned his life on it? And there is no question in this case but that it is true. Then who is to blame? The university would be more to blame than he is. The scholars of the world would be more to blame than he is. The publishers of the world -- and Nietzsche's books are published by one of the biggest publishers in the world -- are more to blame than he.

Rowe, in his book Agency, elaborates on how the issue raised by Darrow resonates today:

As someone who has run public charter schools in low-income communities in the Bronx, I know how debilitating such a narrative [based on racially focused outcomes] can be for a student’s hopes and aspirations. If a teacher were to espouse such a philosophy in our classrooms, it would be grounds for termination. Rather than helping young students develop personal agency and an understanding of the behaviors most likely to propel them into success, this message will only teach what psychologists term learned helplessness … Imagine that instead of the message that “no matter what, you are disadvantaged,” young people of all races understood that nothing is predetermined in their lives and that they themselves have the greatest level of influence over their own futures … In many ways, what I have come to understand tracks with the conclusion of the British government’s recent Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities. Launched in the summer of 2020, the panel was asked to examine why racial disparities there persisted. As explained in the report’s opening statement, “As we met with people in round table discussions ... we were taken by the distinctions being drawn between causes that were external to the individual and those that could be influenced by the actions of the individual himself or herself. As our investigations proceeded, we increasingly felt that an unexplored approach to closing disparity gaps was to examine the extent individuals and their communities could help themselves through their own agency, rather than wait for invisible external forces to assemble to do the job.”

Regarding that subject, Shelby Steele gives his own very interesting take on the debilitating effects of failures to recognize agency at the 17:09 minute mark of this video here and at the 10:30 minute mark of this video here.

And 159 years earlier, former slave and civil rights leader Frederick Douglass said, “color should not be a criterion of rights, neither should it be a standard of duty. The whole duty of a man, belongs alike to white and black.” And even earlier Douglass said “It is evident that the white and black must fall or flourish together. In the light of this great truth, laws ought to be enacted, and institutions established — all distinctions, founded on complexion, ought to be repealed, repudiated, and forever abolished …”

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at how a failure to recognize agency in individual people can lead to one particularly viral meme that ignores it and promotes instead the notion of imposing equality of outcome regardless of individual choices and circumstance.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6.