At a forum on school safety hosted by our local school system, the superintendent of schools was asked the question (at the 53:58-minute mark) “What is being done to hold students accountable who engage in very violent behavior?”

To that question, the superintendent responded (at the 55:05-minute mark):

I think we have to be mindful that when we think of violence and how we define violence, we look at our discipline in regard to the infractions and the behaviors that occur with it. So we just have to be mindful when we use the word violence because we are talking about students who have experienced challenges, who’ve returned to school, and maybe their families are in crisis. There are a number of things that often go on as to why children may have behaviors or experience challenges in school. So I just want us to be mindful when we use that word violence because it’s a very harsh word and it’s a very emotional word because we want what’s best for all of our students.

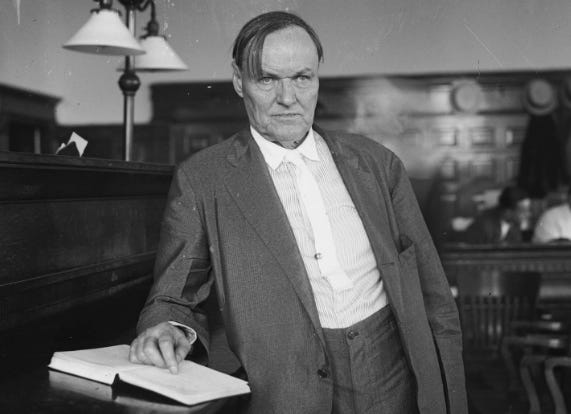

The answer’s focus on the “number of things that often go on as to why children may have behaviors or experience challenges in school” recalls a closing argument made in one of the nation’s most famous murder trials by Clarence Darrow, a lawyer of the early Twentieth Century who was also a leading member of the American Civil Liberties Union. In that trial, Darrow defended two kids from a capital charge for their murder of another child. In his closing argument on behalf of his clients, Darrow also focused on all the things that might contribute to the cause of a child’s violence in an effort to persuade the court that their moral blame should be reduced. To what extent should we find these arguments convincing? That’s the subject of this series of essays.

Darrow’s twelve-hour summary defense of the violence of his clients has been called the finest speech of his career for its defense of “transformative justice” (which includes concepts like “restorative practices”) as an alternative to punishment for violence. So let’s look closely at Darrow’s argument from 1924.

Darrow addressed the court, saying “I want to give some attention to this cold-blooded murder, your Honor. Was it a cold-blooded murder?”

He then went on to detail what he saw as the more relevant larger context of the violence:

[I]t was the senseless act of immature and diseased children, as it was; a senseless act of children, wandering around in the dark and moved by some emotion, that we still perhaps have not the knowledge or the insight into life to thoroughly understand.

He urged the judge to put himself in the position of the two boys who committed the violent act. He said:

Now, your Honor, you have been a boy; I have been a boy. And we have known other boys. The best way to understand somebody else is to put yourself in his place. Was their act one of deliberation, of intellect, or were they driven by some force … Why did they kill little Bobby Franks? … They killed him because they were made that way. Because somewhere in the infinite processes that go to the making up of the boy or the man something slipped, and those unfortunate lads sit here hated, despised, outcasts, with the community shouting for their blood.

He spoke to those related to the victim of the violence:

I know that any mother might be the mother of a little Bobby Franks [the victim of the violence], who left his home and went to his school, and who never came back. I know that any mother might be the mother of Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold [the perpetrators of the violence], just the same. The trouble is this, that if she is the mother of a Nathan Leopold or of a Richard Loeb, she has to ask herself the question: “How came my children to be what they are? From what ancestry did they get this strain? How far removed was the poison that destroyed their lives? Was I the bearer of the seed that brings them to death?” Any mother might be the mother of any of them. But these two are the victims.

Darrow then recited a poem expressing the situation of a child growing up in unfortunate circumstances:

I remember a little poem that gives the soliloquy of a boy about to be hanged, a soliloquy such as these boys might make:

The night my father got me

His mind was not on me;

He did not plague his fancy

To muse if I should be

The son you see.

The day my mother bore me

She was a fool and glad,

For all the pain I cost her,

That she had borne the lad

That borne she had.

My father and my mother

Out of the light they lie;

The warrant would not find them.

And here, 'tis only I

Shall hang so high.

O let not man remember

The soul that God forgot.

But fetch the county sheriff

And noose me in a knot,

And I will rot.

And so the game is ended,

That should not have begun.

My father and my mother

They had a likely son,

And I have none.

And so Darrow moves from the soft emotion of a poem to the hard logic of philosophical reasoning:

I do not know what it was that made these boys do this mad act, but I do know there is a reason for it. I know they did not beget themselves. I know that any one of an infinite number of causes reaching back to the beginning might be working out in these boys' minds, whom you are asked to hang in malice and in hatred and injustice, because someone in the past has sinned against them … [W]hen your are pitying the father and the mother of poor Bobby Franks [the victim], what about the fathers and mothers of these two unfortunate boys, and what about the unfortunate boys themselves, and what about all the fathers and all the mothers and all the boys and all the girls who tread a dangerous maze in darkness from birth to death? Do you think you can cure it by hanging these two? Do you think you can cure the hatreds and the maladjustments of the world by hanging them? You simply show your ignorance and your hate when you say it.

Darrow brings the causal chain down to the cellular level:

Aye, who knew the father and mother and the grandparents and the infinite number of people back of him? Who knew the origin of every cell that went into the body, who could understand the structure, and how it acted? Who could tell how the emotions that sway the human being affected that particular frail piece of clay? It means more than that. It means that you must appraise every influence that moves them, the civilization where they live, and all society which enters into the making of the child or the man!

Darrow then says his logic is already understood by all “intelligent people”:

[I]ntelligent people now know that every human being is the product of the endless heredity back of him and the infinite environment around him. He is made as he is and he is the sport of all that goes before him and is applied to him … This boy [the perpetrator] needed more of home, more love, more directing. He needed to have his emotions awakened. He needed guiding hands along the serious road that youth must travel. Had these been given him, he would not be here today.

Are you convinced now that Darrow (and the school superintendent) are right? Whether you are or not at this point, Darrow went on to say a lot more. He continued the logic of the school superintendent’s essential thesis and, as we’ll see in the next essay, the final links in that chain of reasoning may surprise you.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6.

Many of us think Darrow started this slippery slope...but he was an amazing orator. Looking forward to the next installment!