Thanksgiving Week -- So You Think Your Life is Tough? Check Out Life in Early America – Part 2

It kind of sucked to be rich. And fossil fuels saved the whales.

Following up on our first essay on why you should be more thankful than you are, let’s look at how much it sucked to be rich not too long ago.

When only the rich could afford the most horrific medical care imaginable.

In early America, the irony was that the more money you had, the much worse your health care. That’s because the most sophisticated medicine, as it was understood at the time, involved techniques that today seem more suited to torture chambers.

Many people are familiar with the colonial practice of having leeches suck blood out of patients in the hopes of removing harmful elements from the body. But did you know there was a more common remedy called “purging”? As Larkin writes in his book The Reshaping of Everyday Life: 1790-1840:

“[P]urging” [was] administering massive doses of cathartics, or powerful laxatives. Almost as frequent was “puking,” or dosing heavily with emetics to induce copious vomiting. Other drugs produced different forms of fluid emission like salivation, sweating or frequent urination. Blood, pus, vomit, feces, sweat or urine were the tangible evidence that the dose had “operated.”

In one recorded case, when the leeches treatment didn’t seem to work, a Dr. Isaac Rand

felt compelled to “shave the head and bathe it with ether … blister the whole head, and keep up the discharge with the vesicating ointment; blister the nape of the neck, the temples, and behind the ears …” … Rand was one of a substantial number of American physicians who practiced “heroic medicine,” intervening as vigorously as possible to deplete their patients’ overstimulated systems … Under heroic treatment many patients suffered presumably well-intentioned but sometimes astonishingly severe and protracted assaults on their bodies.

And that was all done without anesthesia.

Cities spread disease faster then, too.

Wealthier people tended to live in the cities, but that’s where disease spread the most. As Larkin writes:

Cities in the United States, as elsewhere in the world, were more dangerous places to live than the countryside. Diseases spread more rapidly among close-packed city populations, and sheer numbers allowed illnesses to become endemic which would have burned themselves out in smaller communities. Because dwellings were crowded onto small sites, privies and wells for drinking water were usually sited dangerously close together. Under such conditions city dwellers were at high risk for intestinal diseases like typhoid and cholera which were transmitted through flies and fecal matter … Endemic in the tropics, the yellow-fever virus was transmitted by the bite of the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which was carried on shipboard from West Indian and South American ports in buckets and other water containers. Sometimes called the “black vomit,” the disease produced a telltale jaundice and killed by destroying the liver and kidneys. “Confined almost exclusively to the seaport towns and cities,” as the Philadelphia physician William Currie observed, yellow fever also produced great fear because it was exceedingly deadly, killing up to one-half of its victims. The single most devastating American epidemic of the early national years was the onslaught of yellow fever that killed one out of every ten Philadelphians in 1793. During the summer and fall of that year Philadelphia, then both the capital and the largest metropolis of the United States, was a ghastly place, paralyzed with fear and with the gravediggers’ cry “bring out your dead” ringing in its streets. “Acquaintances and friends,” recalled the publisher Matthew Carey, “avoided each other in the streets…A person with crape or any appearance of mourning was shunned like a leper.” The visitation left some Americans with a sense of imminent doom and others with the fear that urban epidemics might make city living impossible.

Poor lighting.

Today, we live with light available everywhere, at all times. Our phones even have flashlights in them. But back in the day, light at night glimmered like gold, and was just as valuable. As Larkin writes:

At night, the meagerness of light available from candles or oil lamps drew people close together or sent them to bed … And “sevenfold worse in its way even than washing day,” [Harriet Beecher] Stowe thought, was that annually recurring winter’s day when women worked from “day-dawn” to late at night dipping strings into melted beef tallow to make the year’s supply of candles.

Then, around 1798, there was a revolution in home lighting:

A far more dramatic improvement in illumination came with the development of the Argand lamp in 1798 and its successor, the “astral lamp.” Expensive to buy and burning highly refined and costly sperm oil—the precious commodity for which the whale ship Pequod’s crew hunted in Moby Dick—each was equivalent to about ten candlepower, far more than the total lighting most households could produce. They were rare and splendid objects to ordinary folk.

As Steven Johnson describes in his book “How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World”:

In a 1751 letter, Ben Franklin described how much he enjoyed the way the new candles “afford a clear white Light; may be held in the Hand, even in hot Weather, without softening; that their Drops do not make Grease Spots like those from common Candles; that they last much longer, and need little or no Snuffing.” Spermaceti light quickly became an expensive habit for the well-to-do. George Washington estimated that he spent $15,000 a year in today’s currency burning spermaceti candles.

Spermaceti oil was expensive because of all the effort that had to go into obtaining it, including catching the whale in the first place. If you think your job is bad, think about what it was like to be the person (often a smaller child) who had to extract the sperm oil from inside the stinking, festering head of its carcass. Here’s Johnson again:

Extracting the spermaceti was almost as difficult as harpooning the whale itself. A hole would be carved in the side of the whale’s head, and men would crawl into the cavity above the brain—spending days inside the rotting carcass, scraping spermaceti out of the brain of the beast. It’s remarkable to think that only two hundred years ago, this was the reality of artificial light: if your great-great-great-grandfather wanted to read his book after dark, some poor soul had to crawl around in a whale’s head for an afternoon.

But thanks to innovation and modern science, things soon improved for everyone – even the whales -- due to the discovery of how fossil fuels could be used for lighting. As Michael Shellenberger writes in “Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All”:

Rising demand for whale oil led entrepreneurs to look for alternatives. One of them was named Samuel Kier. In 1849, a doctor prescribed Kier’s wife “American Medicinal Oil,” petroleum, to treat an illness. His idea wasn’t new. The Iroquois had used petroleum as an insect repellent, salve, and tonic for hundreds of years. When his wife felt better, Kier recognized a business opportunity. He launched his own brand, “Kier’s Petroleum, or Rock Oil,” and sold bottles for fifty cents through a sales force traveling through the region by wagon. Kier was ambitious and sought other uses for his product. A chemist recommended distilling it and using it as lighting fluid. Kier’s contribution to the emerging petroleum revolution was the creation of the first industrial-scale refinery in downtown Pittsburgh. A group of New York investors believed Kier had created a major business opportunity. They hired an itinerant and disabled engineer with good expertise in salt drilling to poke around in Pennsylvania for petroleum. In 1859, the man, Edwin Drake, drilled and hit a gusher of oil near Titusville, Pennsylvania. The discovery of the Drake Well led to widespread production of petroleum-based kerosene, which rapidly took over the market for lighting fluids in the United States, thus saving whales, which were no longer needed for their oil. At its peak, whaling produced 600,000 barrels of whale oil annually. The petroleum industry achieved that level less than three years after Drake’s oil strike. In a single day, one Pennsylvania well produced as much oil as it took a whaling voyage three or four years to obtain, a dramatic example of petroleum’s high power density. In 1861, two years after Drake’s oil strike, Vanity Fair magazine published a cartoon showing sperm whales standing on their fins and dressed in tuxedos and ball gowns, toasting one another with champagne at a fine celebration. The caption read, “Grand ball given by the whales to celebrate the discovery of the oil wells in Pennsylvania.” While whalers over-hunted whales, historians conclude that “there is no evidence that American whaling contracted because of a serious shortage of whales.” The creation of a substitute with a much higher power density was sufficient. This is an important lesson since it means we need not wait for inferior products, environmentally and otherwise, to run out before replacing them.

While we’re on the subject of progress in lighting, let’s carry that story forward, to help us appreciate even more the times in which we live now. Another great example of how the ingenuity spurred by the Industrial Revolution dramatically improved our lives is the light bulb. When William Nordhaus traced the history of lighting during the past two centuries, he concluded that we vastly understated its impact on our standard of living. George Washington calculated that it cost him more than $1,000 each year in today’s dollars to burn a spermaceti candle for five hours a night. Nordhaus (who won the Nobel Prize in economics) looked at the average wage of workers through the years and calculated how much time a worker would have to work to pay for one hour of lighting used at the time to read a book at night for one hour. The following chart summarizes his findings.

And here’s his chart showing the dramatic fall in the price of light, and the labor required for the average person to pay for it, over time.

Another great graphical illustration of the great reduction in the cost of lighting can be found here.

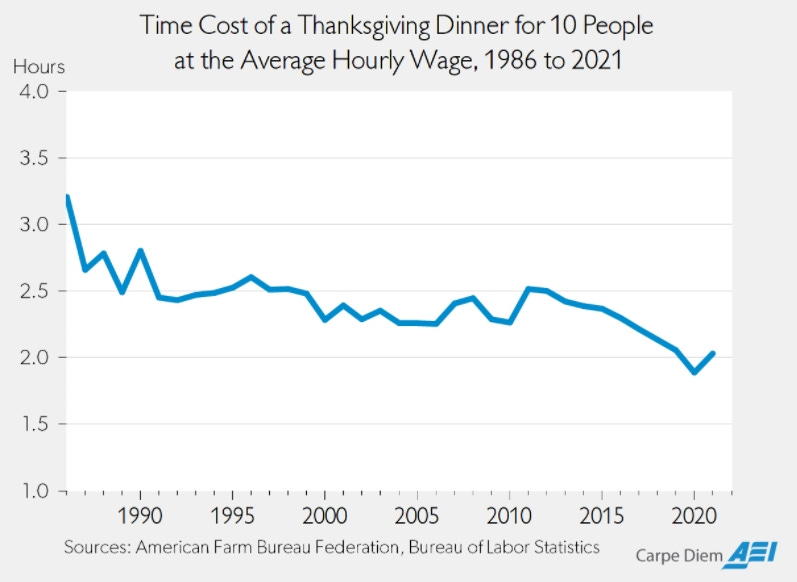

Dramatic decreases in the price of energy, and food production, has also led to a dramatic decrease in the time cost of preparing a traditional Thanksgiving dinner, not just compared to 200 years ago, but even over the last thirty years. As Mark Perry explains:

The fact that a family in America can celebrate Thanksgiving with a classic turkey feast for ten people for just over $5 per person and at a “time cost” of only two hours of work at the average hourly wage for one person means that we really have a lot to be thankful for on Thanksgiving: an abundance of cheap, affordable food despite the challenges of the pandemic, supply chain issues, and rising energy prices. The average American earns enough money by the time of his or her morning coffee break working on just one day to be able to afford the cost of a traditional Thanksgiving meal for ten.

Yet another reason to have been thankful on Thanksgiving!

In the next and final essay in this series we’ll explore even more reasons why you should be so thankful you’re living today instead of yesterday.

Thanks for all your posts. I find them both interesting and enlightening.