Thanksgiving Week -- So You Think Your Life is Tough? Check Out Life in Early America – Part 1

Crippling physical labor and cooking in ashes.

In a previous post, I discussed the benefits of the Stoic worldview, and quoted William B. Irvine’s A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy. In that book, Irvine reminds us the study of history should make us all feel good about the time we live in today, because things are so much better than they used to be. As he writes:

[W]e can do some historical research to see how our ancestors lived. We will quickly discover that we are living in what to them would have been a dream world—that we tend to take for granted things that our ancestors had to live without, including antibiotics, air conditioning, toilet paper, cell phones, television, windows, eyeglasses, and fresh fruit in January.

That tendency to take progress for granted has sometimes been called “the Tocqueville effect” -- a phenomenon in which, as the standard of living gets much better, people’s expectations for yet further improvement rise even faster, such that people become dissatisfied with the pace of progress even while it’s improved dramatically. (It’s called “the Tocqueville effect” after the French observer Alexis de Tocqueville, who wrote the following in his 1856 book The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856), discussing the French Revolution: “The regime which is destroyed by a revolution is almost always an improvement on its immediate predecessor, and experience teaches that the most critical moment for bad governments is the one which witnesses their first steps toward reform.”)

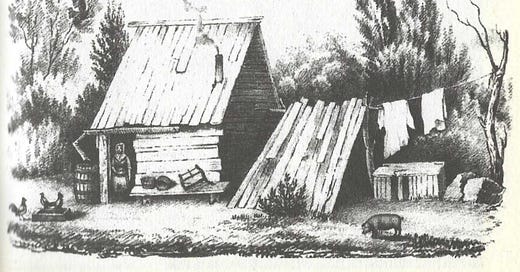

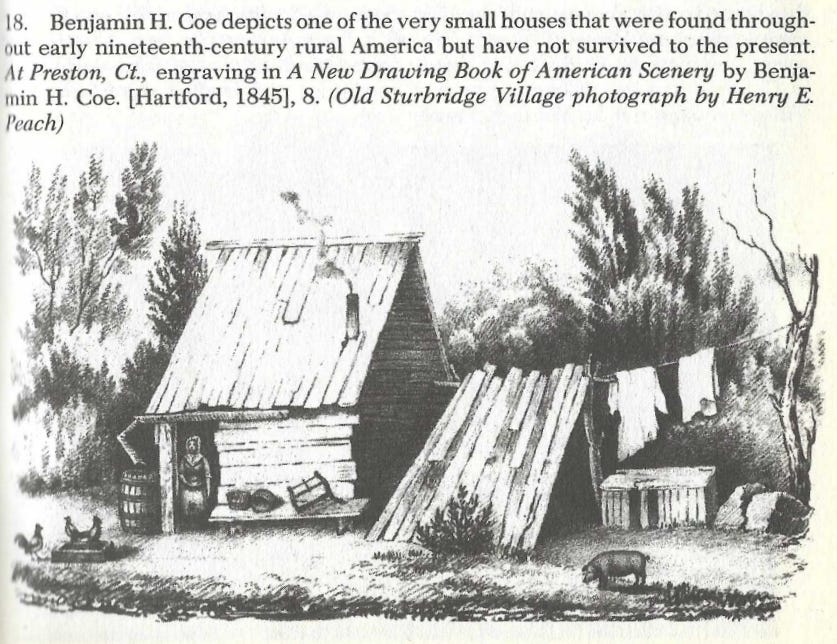

To counter that “Tocqueville effect,” I occasionally revisit Jack Larkin’s excellent book “The Reshaping of Everyday Life: 1790-1840 (Everyday Life in America),” a remarkable portrait of living conditions for the typical person in early America.

You probably don’t feel sufficiently thankful for what you have today. So let’s check out what life was like just a couple hundred years ago.

Muscle Motors

Today, if you want to get something done you’re likely to search the internet for a service that will get the job done for you. But in early America, you’d ask yourself “Am I, or my animals, or my slaves, physically strong enough to do that?” As Larkin writes:

In the agricultural world of 1800, centuries-old limits on the tools and motive power of work held fast. Muscle power, with some assistance from falling water, determined what could and could not be done. On American farms and plantations, horses and oxen hauled loads, pulled plows and harrows and turned cider mills and cotton gins … Southerners used oxen, horses and a few mules, as well as the “flocks of slaves passing over the land with hoes” that observers noted on plantation fields. Waterwheels drove small-scale mills for grinding grain, sawing timber and fulling handwoven woolen cloth. Almost everything else fell to human effort—felling trees, hauling wood and water, digging stones, hoeing weeds, picking cotton, mowing hay, harvesting grain, husking corn, churning butter, pressing cheese. Where streams were too sluggish, or mills had not yet been built, women and children pounded corn in “hominy blocks” or ground grain in hand mills, and teams of men pit sawed lumber by hand.

Physical labor was so demanding, it twisted men into the shape of plows: “The great physical demands of unmechanized agriculture gave men a distinctively ponderous gait and posture. Despite their strength and endurance, farmers were ‘heavy, awkward and slouching in movement,’ and walked with a ‘slow inclination from side to side.’” So however exhausted you might be at the end of any given day today, at least you haven’t been crushed into deformity.

Peloton exercise bike? Try a foot wheel.

Back then, women didn’t ride exercise bikes in their spare time. Their days were dominated by pumping foot wheels: “In most farm households the ‘buzz of the foot wheel,’ the smaller foot-powered spinning wheel that produced tow and linen thread … were a persistent background music” that could be heard from long distances.

Cooking

Upset the exact cookware you need is in the dirty dishwasher, so you have to use something similar but not quite right? Well back in early America, unless you were rich, you might have just a single dish-kettle and have to resort to baking your bread directly “in the ashes” to make a form of barbecue bread. And there were no salt shakers or tea bags. As Larkin writes, “Salt, sugar, spices and coffee had to be taken in bulk form, ground and pounded. Housewives hauled water, killed chickens, set their children to search for eggs in the barnyard and harvested vegetables from the garden or the root cellar.” You didn’t get it off the shelf. You pulled it from the earth.

Washing clothes

Are you as amused as I am when people today complain “I did laundry all day”? Because … they didn’t do the laundry all day. The washing machine did the laundry all day. They put the dirty clothes in the machine, and moved the clean clothes to the dryer, but the machine did the work. Back in early America, however:

On washing days … women woke up “long before sunrise,” as Ellen Rollins remembered, to scrub and pound clothes, plunging their arms up to the elbows in tubs of near-boiling water and homemade soft soap. After repeated washing and rinsing, they emerged in the afternoon with “bleached, par-boiled fingers” to spread their laundry out to dry.

Today, the machine does the work, and the people just do the complaining, at least where people have washing machines. Many don’t around the world. So to get an even greater appreciation of the magic that is the washing machine, watch Hans Rosling’s wonderful lecture, which ends with this immortal ode: “And what we said, my mother and me [after she got her first washing machine], was ‘Thank you, industrialization!’ ‘Thank you, steel mill!’ ‘Thank you, power station!’ ‘And thank you, chemical processing industry that gave us time to read books!’”

No free lunch, and no free favors.

Back then, most people had to work so hard for what they had in early America that it was assumed that work would be done for others in return for any favors they did for you:

Economic life was deeply, inextricably entangled in social life. Visits and economic transactions were usually indistinguishable. In Western and Southern settlements, “changing,” or the “borrowing system,” as the people of Illinois called it, often worked with oral accounting held in the memory. “I expect I shall have to do a turn of work for this,” said her new Ohio neighbors to the uncomprehending Frances Trollope when she loaned utensils or gave foodstuffs; “you may send for me when you want me.” She thought it an attempt to avoid saying “thank you” for neighborly kindness. But they were trying to involve her in their economic web, in which kindness was far less important than maintaining patterns of reciprocal obligation.

In fact, back then it may have been easier to repay someone else by performing work than to pay them in cash, since the currency was so confusing:

There was no national or state paper money, and in the years around 1800, money primarily meant specie—gold and silver coin. The actual coins which Americans used were usually not their own country’s currency at all. Before gold was discovered in California in 1849, the federal mint did not coin enough precious metal. A bewildering variety of foreign coins circulated: Dutch rix-dollars, Russian kopecks, as well as French and English specie. Most of the coins Americans used were the silver dollars, halves, quarters, eighths and sixteenths minted in Mexico and in the South American republics where silver was abundant. With the variegated coinage, the need to state final amounts in U.S. currency, and “the traditional but imaginary shillings,” as Underwood noted, “there was a rare confusion.”

As mysterious as the working of Bitcoin might be to some today, at least its value is easily quantified in a computerized ledger.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone, and in the next essay we’ll explore even more reasons to be thankful.