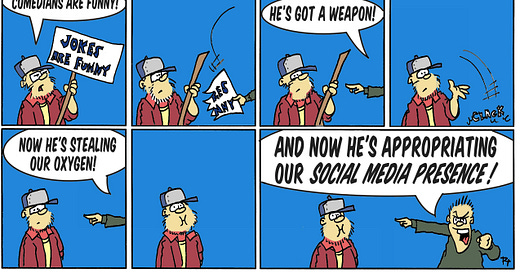

(The above cartoon relates to this incident, which turns out to be super-relevant to today’s Part 2 essay on the philosophy of Stoicism.)

Following up on Part 1 of my essay on Stoicism (a philosophy that says it makes little sense to get upset about things you can’t control, like what other people say), it’s worth pointing out that getting mad for no good reason isn’t just a waste of time. It can make you prone to falsity as well.

Researchers have found that anger actually makes people more susceptible to misinformation than people in a more neutral emotional state. The same researchers also found that study participants who were angry tended to be more confident in the accuracy of their memories. But among those participants, increased confidence was actually associated with decreased accuracy. In contrast, among those in a neutral emotional state (the more Stoic among them), increased confidence was associated with increased accuracy. So keeping your emotions in check not only makes you calmer. It also tends to make you more accurate in your understanding of the world.

The Stoic mindset also comes in handy when dealing with politics, a field rife with emotion that could otherwise draw people down the road to anger (and inaccuracy). As William B. Irvine writes in his book A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy:

Now that we understand the technique of internalizing our goals, we are in a position to explain what would otherwise seem like paradoxical behavior on the part of Stoics. Although they value tranquility, they feel duty-bound to be active participants in the society in which they live. But such participation clearly puts their tranquility in jeopardy. One suspects, for example, that Cato would have enjoyed a far more tranquil life if he did not feel compelled to fight the rise to power of Julius Caesar—if he instead had spent his days, say, in a library, reading the Stoics. I would like to suggest, though, that Cato and the other Stoics found a way to retain their tranquility despite their involvement with the world around them: They internalized their goals. Their goal was not to change the world, but to do their best to bring about certain changes. Even if their efforts proved to be ineffectual, they could nevertheless rest easy knowing that they had accomplished their goal: They had done what they could do. A practicing Stoic will keep the trichotomy of control firmly in mind as he goes about his daily affairs. He will perform a kind of triage in which he sorts the elements of his life into three categories: those over which he has complete control, those over which he has no control at all, and those over which he has some but not complete control. The things in the second category—those over which he has no control at all—he will set aside as not worth worrying about. In doing this, he will spare himself a great deal of needless anxiety. He will instead concern himself with things over which he has complete control and things over which he has some but not complete control.

As I found out while I was a counsel to the House Judiciary Committee, there is much in politics beyond one’s control. Members of Congress have some concerns motivated not by principle alone, but also by the demands of their constituents in 435 separate congressional districts. Members of Congress may have implicit or explicit commitments to other Members or donors beyond your knowledge as a staff person on the committee — and they may have many other incentives, based on influences you couldn’t possibly be aware of. In that sense, politics is like a weather system, and it often makes as little sense to get upset about the political position of one Member or another as it does to get upset when it rains. While working for Congress, I was fond of the phrase “Embrace the chaos.”

Despite the unfortunate popular association of Stoicism with cold-heartedness and a lack of emotion, that’s not an accurate description of the philosophy as developed by its practitioners. For example, it’s not that I’m not passionate about ideas (I am). But many circumstances are outside the realm of ideas, and inside the realm of the weather (and should be treated accordingly). As Irvine explains:

It isn’t, as those ignorant of the true nature of Stoicism commonly believe, that we will stop experiencing emotion. We will instead find ourselves experiencing fewer negative emotions. We will also find that we are spending less time than we used to wishing things could be different and more time enjoying things as they are. We will find, more generally, that we are experiencing a degree of tranquility that our life previously lacked.

As Booker T. Washington wrote, “The persons who accomplish the most in this world … are those who are constantly seeing and appreciating the bright side as well as the dark side of life.”

Unfortunately today, proponents of “identity politics” who see a world full of “systemic oppression” are encouraging more people, especially young people, to see themselves as helpless victims. Irvine speaks to them when he writes:

Many of us have been persuaded that happiness is something that someone else, a therapist or a politician, must confer on us. Stoicism rejects this notion. It teaches us that we are very much responsible for our happiness as well as our unhappiness. It also teaches us that it is only when we assume responsibility for our happiness that we will have a reasonable chance of gaining it. This, to be sure, is a message that many people, having been indoctrinated by therapists and politicians, don’t want to hear.

Researchers have studied people with what they call a “Tendency for Interpersonal Victimhood” (TIV), which is defined as “an ongoing feeling that the self is a victim.” Those researchers ran several studies assessing TIV, which is a world view that’s the very opposite of Stoicism in many ways. The researchers concluded:

[Our studies] indicated that the TIV scale is best conceptualized as a hierarchical model with four method factors, representing the four dimensions of TIV; i.e., the need for recognition, moral elitism, lack of empathy, and rumination [which refers to a focus of attention on the symptoms of one’s distress, and its possible causes and consequences rather than its possible solutions] … Behaviorally, high-TIV individuals were less willing to forgive others after an offense, and more likely to seek revenge rather than avoidance and behave in a revengeful manner … The clinical literature on victimhood may explain how moral elitism, lack of empathy and the desire for revenge can manifest simultaneously among high-TIV individuals, and thus enable them to feel morally superior even though they exhibit aggression … From a motivational point of view, TIV seems to offer anxiously attached individuals an effective framework for their insecure relations that involve gaining others’ attention, recognition, and compassion, and at the same time experiencing and expressing negative feelings.

What does that all mean in layman’s terms? As the study was described in Psychology Today:

The researchers developed a Victim Signaling Scale, ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = always. It asks how often people engage in certain activities. These include: “Disclosed that I don’t feel accepted in society because of my identity.” And “Expressed how people like me are underrepresented in the media and leadership.” They found that Victim Signaling scores highly correlated with dark triad scores (r = .35). [“Dark triad scores” are a pretty well-studied cluster of socially aversive traits (namely narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy).] This association held after controlling for gender, ethnicity, income, and other factors that might make people vulnerable to mistreatment. Participants also completed a questionnaire that measured Virtue Signaling. They rated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements about moral traits like being fair, compassionate, and honest. A sample statement is “I often buy products that communicate the fact that I have these characteristics.” They also found that Virtue Signaling was significantly correlated with dark triad scores (r = .18). They replicated this association in a follow-up study. This time they used a different, more robust, dark triad scale. They then found a stronger correlation between the dark triad traits and victim signaling (r = .52). The researchers also found that victim signaling negatively correlated (r = -.38) with Honesty-Humility. This is a personality measure of sincerity, fairness, greed avoidance, and modesty. This suggests that victim signalers may be greedier and less honest than those who do not signal victimhood. Beyond measuring responses to questionnaires, they also had participants play a game. Basically, it was a coin flip game in which participants could win money if they won. Researchers rigged the game so that participants could easily cheat. Participants could claim they won even if they didn’t, and thus obtain more money. Victim signalers were more likely to cheat in this game. The researchers again found that these results held after controlling for ethnicity, gender, income, and other factors. Regardless of personal characteristics, those who scored higher on dark triad traits were more likely to be victim signalers. And may be more likely to deceive others for material gain. The researchers then ran a study testing whether people who score highly on victim signaling were more likely to exaggerate reports of mistreatment from a colleague to gain an advantage over them. Participants were told to imagine they worked with another intern. And that they were competing to land a job. Participants were told, “You keep noticing little things about the way the intern talks to you. You get the feeling the other intern may have no respect for your suggestions at all. To your face, the intern is friendly, but something feels off to you.” Then participants engaged in the feedback performance of the intern. Then they completed the Victim Signaling scale. Victim signalers were more likely to exaggerate the negative qualities of their competitor. They were more likely to agree that the intern “Made demeaning or derogatory remarks,” or “Put you down in front of coworkers.” Nothing in the description of their colleague indicated that they performed these actions. But victim signalers were more likely to report that they did. As the authors note, real victims exist … Still, alongside victims, there are social predators among us. In whatever milieu they find themselves in, they will enact the strategies that maximize the rewards of material resources … Today, those with dark triad traits might find that the best way to extract rewards is by making a public spectacle of their victimhood and virtue.

Yikes. Perhaps best to try avoiding such people when possible in one’s personal life. As Irvine writes:

Besides advising us to avoid people with vices, Seneca advises us to avoid people who are simply whiny, “who are melancholy and bewail everything, who find pleasure in every opportunity for complaint.” He justifies this avoidance by observing that a companion “who is always upset and bemoans everything is a foe to tranquility.”

Perhaps it should be no surprise that people who tend toward victimhood aren’t big fans of free markets, either, since free markets require people to get along long enough to work together freely. And it seems people only got around to getting better at controlling their own emotions when free markets became the dominant mode of production. As John Kasson writes in “Rudeness and Civility: Manners in Nineteenth-Century Urban America”:

As Norbert Elias first observed a half century ago, a rising standard of emotional control is one of the most striking, if hitherto neglected, historical developments in modern northern European (and later, American) society. Before the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, extremes of jubilant laughter, passionate weeping, and violent rage were indulged with a freedom that in later centuries would not be permitted even to children.

Then, once free markets developed and people had to work together, things changed. According to Kasson, “Emerging out of a complex intersection of causes … there appeared in the eighteenth century a decisive shift in notions of appropriate behavior, including a new stress upon emotional control that was profoundly extended in the course of the nineteenth century with the development of an urban-industrial capitalist society.” And so The Illustrated Manners Book proclaimed in 1855: “Command yourself; the man who is liable to fits of passion; who cannot control his temper, but is subject to ungovernable excitements of any kind, is always in danger. The first element of a gentlemanly dignity is self-control … This quality is to be acquired when it is wanting; and it may be, to an extraordinary degree, by a steady effort to bear up against small annoyances.” That quality seems to be increasingly sparse today, especially in places largely insulated from free markets (say, colleges and universities) and interpersonal contact (like social media).

So the next time you’re tempted to make a petty ad hominem attack on social media or elsewhere, channel instead the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, who said: “The happiness of your life depends on the quality of your thoughts.”

Finally, a good video on why you shouldn’t care what other people think can be found here, at the Daily Stoic.

Links to other essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; How to Teach How to Think