Are you one of those people who gets really upset about what other people say? Would you like to train yourself to react differently? If so, the practical philosophy of Stoicism is for you!

A while back, the term Stoicism was Greek to me. And it is Greek – ancient Greek. It’s a philosophy that was popularized by people with names like Seneca, and later the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, and it gets its name from the Greek word for a painted porch, which is where early adherents of Stoicism gathered to talk about it. But it’s origins aside, it’s a practical philosophy based more on real-world human psychology than ethereal theoretical musings.

The gist of the Stoic philosophy is that you should focus only on the things you can control, and not be bothered by the things you can’t control. Makes sense, right? Why get upset when it rains? Your getting upset won’t change the weather. Focus instead on finding an umbrella -- and also be thankful it isn’t flooding. When you focus on what you can control, you get to devote more energy toward solving a problem instead of suffering under distracting emotional angst -- and you get to give yourself the space to appreciate what you have.

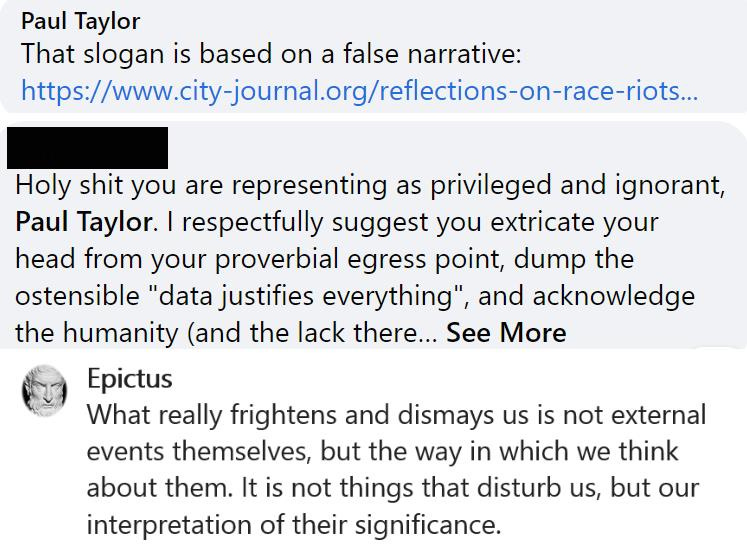

In their excellent book “The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure,” Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt describe how the Stoic philosophy can help anyone who might be overly sensitive to what other people say or do. They open one of their book chapters with the following quote from the Stoic philosopher Epictetus, who lived between the first and second centuries: “What really frightens and dismays us is not external events themselves, but the way in which we think about them. It is not things that disturb us, but our interpretation of their significance.” Lukianoff and Haidt go on to write:

We opened this chapter with a quotation from the Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus, but we could just as easily have quoted Buddha (“Our life is the creation of our mind”) or Shakespeare (“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so”) or Milton (“The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven”) … The more ways your identity can be threatened by casual daily interactions, the more valuable it will be to cultivate the Stoic [] ability to not be emotionally reactive, to not let others control your mind and your cortisol levels [the body’s main stress hormone]. The Stoics understood that words don’t cause stress directly; they can only provoke stress and suffering in a person who has interpreted those words as posing a threat.

Christianity as a way of life was influenced by the philosophy of Stoicism. The apostle Paul met with Stoics during his stay in Athens, reported in Acts 17:16–18, and in his letters, Paul drew from his knowledge of Stoic philosophy, using Stoic terms and metaphors to assist his new Gentile converts in their understanding of Christianity. For example, below are comparisons of the teachings of Seneca, a prominent Stoic who lived contemporaneously with Jesus, and Jesus himself.

“It is a petty and sorry person who will bite back when he is bitten.” -- Seneca

“If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also.” -- Jesus

“You look at the pimples of others when you yourselves are covered with a mass of sores.” -- Seneca

“And why do you look at the speck in your brother’s eye, but do not consider the plank in your own eye?” -- Jesus

“If my wealth should melt away it would deprive me of nothing but itself, but if yours were to depart you would be stunned and feel you were deprived of what makes you yourself. With me, wealth has a certain place; in your case it has the highest place. In short, I own my wealth, your wealth owns you.”-- Seneca

“Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and decay destroy, and thieves break in and steal … No one can serve two masters. He will either hate one and love the other, or be devoted to one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon.” -- Jesus

“It’s in keeping with Nature to show our friends affection and to celebrate their advancement, as if it were our very own.” -- Seneca

“Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself” -- Jesus

And consider William B. Irvine’s observation in his book A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy, that:

The Stoics are not alone in harnessing the power of negative visualization. Consider, for example, those individuals who say grace before a meal. Some presumably say it because they are simply in the habit of doing so. Others might say it because they fear that God will punish them if they don’t. But understood properly, saying grace—and for that matter, offering any prayer of thanks—is a form of negative visualization. Before eating a meal, those saying grace pause for a moment to reflect on the fact that this food might not have been available to them, in which case they would have gone hungry. And even if the food were available, they might not have been able to share it with the people now at their dinner table. Said with these thoughts in mind, grace has the ability to transform an ordinary meal into a cause for celebration.

Stoicism was studied in various ways by many American Founding Fathers as well. George Washington was so fond of a play about the Roman Stoic Cato that he had the play performed for the troops at Valley Forge. Carl J. Richard examines the influence of Stoicism on central Founders in his book “The Founders and the Classics: Greece, Rome, and the American Enlightenment,” writing that

the founders perceived the nature and purpose of wisdom in Stoic terms. Even George Washington, unphilosophical by nature, imbibed Stoicism at an early age. The Fairfaxes, whom Washington considered his second family, read Marcus Aurelius and the other Stoics. At the age of seventeen, Washington read [an] English translation of Seneca’s principle dialogues. As Samuel Eliot Morison noted: “The mere chapter headings are the moral axioms that Washington followed through life.”

The works of Seneca were next to Thomas Jefferson’s bed when he died. And as Carl Richard writes, “In 1819 [Jefferson] declared: “Epictetus and Epicurus give laws for governing ourselves, Jesus a supplement of the duties and charities we owe to others.”

The economist Adam Smith, who also influenced the Founders, was himself influenced by the writings of the Stoic Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius.

I’ve found, especially on social media, that people who don’t generally share the Stoic philosophy tend to advocate for more government control over lots of things. As comedian John Cleese has said, “If you can’t control your own emotions, you’re forced to control other people’s behavior. That’s why the touchiest, most oversensitive and easily upset must not set the standard for the rest of us.”

When you can’t control negative emotions you feel when someone says or does something you don’t like, you’ll tend to resort to demanding that other people (or the government) stop whatever it is that upsets you. Wouldn’t it be much better to just not get upset in the first place?

And if you need a distraction from anger, just look at the wonderful things around you. Or watch this video about how humans come into being, or go here or here to see how much things have improved over just the last couple hundred years.

Or, if you’re a “people person,” think of how these advances have led to the growth in human population such that half of all human experience has occurred after 1309, and 15 percent of all human experience ever is happening right now.

Now, some people don’t like that there are more people on the planet. (Not me, I’m a people person.) But in a broader context, as one philosopher has written, if happiness is a good thing -- and in fact, most public policy is premised in some way on reducing unhappiness on net -- then the existence of more people who can experience more happiness on net must be a good thing:

Most people live lives that are, on net, happy. For them to never exist, then, would be to deny them that happiness. And because I think we have a moral duty to maximize the amount of happiness in the world, that means that we all have an obligation to make the world as populated as can be.

In that sense, people who raise generally happy and productive children are perhaps performing the greatest public service.

And if you’re the kind of person who’s a kid at heart, having kids allows you to experience that child-like wonder of the world all over again, this time through your kids’ eyes. As Irvine writes in A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy:

One reason children are capable of joy is because they take almost nothing for granted. To them, the world is wonderfully new and surprising. Not only that, but they aren’t yet sure how the world works: Perhaps the things they have today will mysteriously vanish tomorrow. It is hard for them to take something for granted when they can’t even count on its continued existence. But as children grow older, they grow jaded. By the time they are teenagers, they are likely to take almost everything and everyone around them for granted. They might grumble about having to live the life they are living, in the home they happen to inhabit, with the parents and siblings they happen to have. And in a frightening number of cases, these children grow up to be adults who are not only unable to take delight in the world around them but seem proud of this inability. They will, at the drop of a hat, provide you with a long list of things about themselves and their life that they dislike and wish they could change, were it possible to do so, including their spouse, their children, their house, their job, their car, their age, their bank balance, their weight, the color of their hair, and the shape of their navel. Ask them what they appreciate about the world—ask them what, if anything, they are satisfied with—and they might, after some thought, reluctantly name a thing or two.

So if you’re one of those grumbling types, you might consider taking a trip back to your own childhood, through your own kids if you have them. As Irvine writes, “Parents do lots of things for their children, but Stoic parents—and, I suspect, good parents in general—don’t think of parenting as a burdensome task requiring endless sacrifice; instead, they think about how wonderful it is that they have children and can make a positive difference in [their] lives.”

Links to other essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; How to Teach How to Think