Sources of Bias in Reasoning – Part 4

How “common enemy identity politics” subverts the goal of mutual understanding.

This essay continues our examination of what Keith Stanovich, in his book The Bias That Divides Us: The Science and Politics of Myside Thinking, calls “myside bias,” namely our tendency to “evaluate evidence, generate evidence, and test hypotheses in a manner biased toward our own prior beliefs, opinions, and attitudes.” The last essay concluded with the thought that just as we might realize that “depersonalizing” our beliefs is necessary to help us all arrive at more universal truths, an essentially personalizing intellectual movement has come to predominate on college campuses, one that Stanovich calls “common enemy identity politics.” That’s the subject of the current essay.

In her book Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations, Amy Chua describes the liberal vision of yesteryear:

Fifty years ago, the rhetoric of pro–civil rights, Great Society liberals was, in its dominant voices, expressly group transcending, framed in the language of national unity and equal opportunity. Introducing the bill that eventually became the Civil Rights Act of 1964, John F. Kennedy famously said: “This is one country. It has become one country because all of us and all the people who came here had an equal chance to develop their talents. We cannot say to ten percent of the population that you can’t have that right; that your children cannot have the chance to develop whatever talents they have.” In his most famous speech, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed: “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable Rights of Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” While more radical black power movements, led by activists like Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and the Nation of Islam’s Elijah Muhammad, espoused a more overtly racial, pro-black, or even antiwhite agenda, King’s ideals—the ideals that captured the imagination and hearts of the public and led to real change—transcended group divides and called for an America in which skin color didn’t matter. Leading liberal philosophical movements of that era were similarly group blind and universalist in character. John Rawls’s enormously influential A Theory of Justice, published in 1971, called on people to imagine themselves in an “original position,” behind a “veil of ignorance,” in which they could decide on their society’s basic principles without regard to “race, gender, religious affiliation, [or] wealth.” At roughly the same time, the idea of universal human rights proliferated, advancing the dignity of every individual as the foundation of a just international order. As Will Kymlicka would later point out, the international human rights movement deliberately elevated individual rights as opposed to group rights: “Rather than protecting vulnerable groups directly, through special rights for the members of designated groups, cultural minorities would be protected indirectly, by guaranteeing basic civil and political rights to all individuals regardless of group membership.”

But as Stanovich writes, while that vision still exists among many today, it exists mainly outside formerly “liberal” institutions:

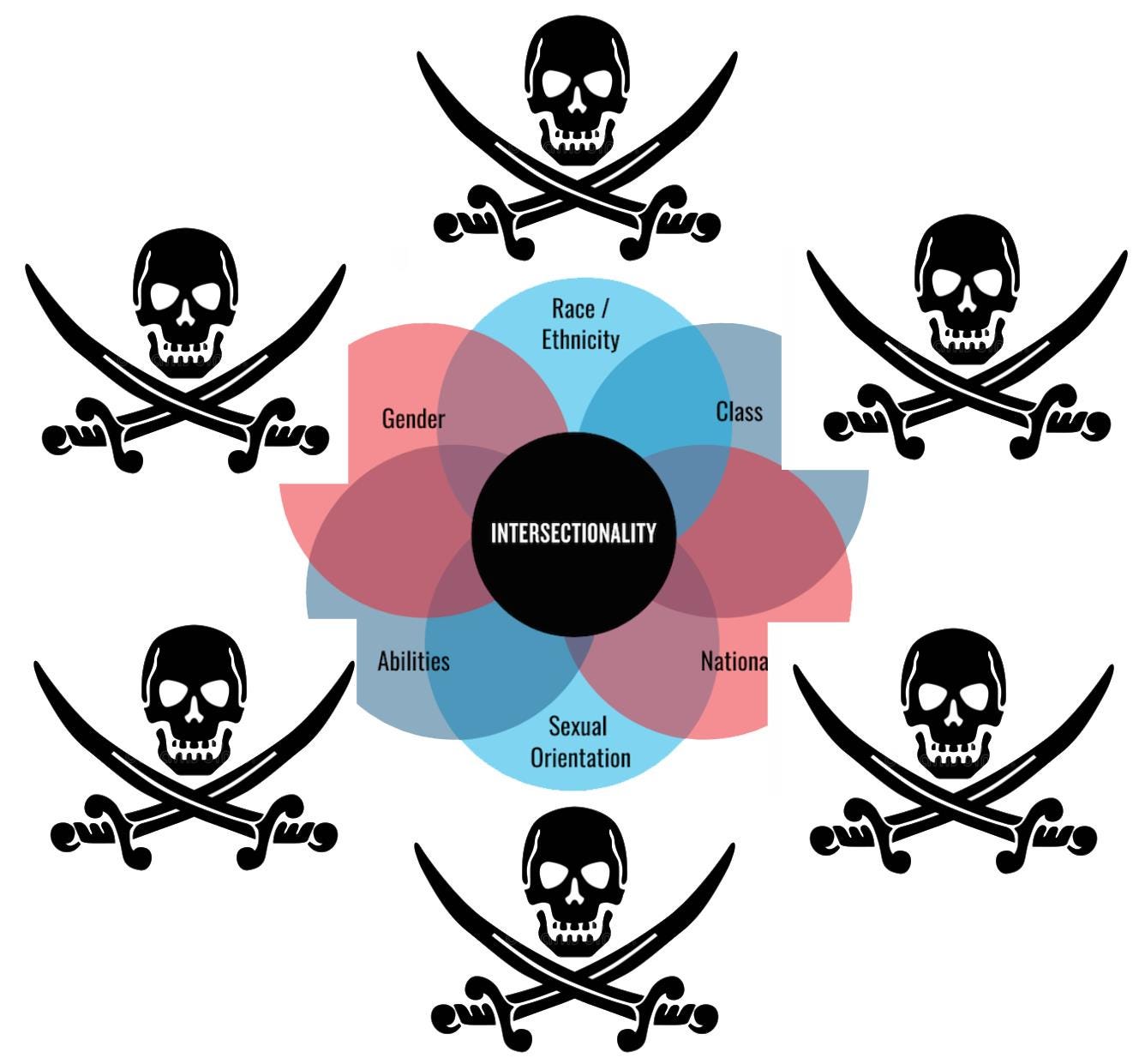

If we are to understand the toxic role that identity politics plays in cultural and political discourse, we need to focus on the version of it that specifically poisons intellectual debate—the version that has turned university campuses from lively forums of contending ideas into encampments of groupthink. Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt (2018) do us a service by clearly differentiating two kinds of identity politics: the “common-humanity” kind and the “common-enemy” kind. Common-humanity identity politics, the kind practiced by Martin Luther King Jr., emphasizes a universalistic common ground we all should aspire to, but points out that certain groups are being denied the dignity and rights that all of us should have under a universalistic conception of society. Common-humanity identity politics presents no problem for reasoned debate in the university communications commons. We would not have a crisis in academia if this were the version of identity politics that had gained currency there … [T]he rampant myside bias that seeks to stifle intellectual debate on university campuses would not be fueled by an identity politics of the kind promoted by Martin Luther King Jr. It is, however, fueled by the common-enemy identity politics … Common-enemy identity politics views society as composed of massive social forces working on very large demographic categories of people. These forces are largely power relations that make people “privileged” (defined as “having the power to dominate”) or “oppressed,” depending upon the conjunction of their demographic characteristics (race, gender, sexual orientation, and so on). Completely unlike common-humanity group politics, where no one has to lose if common rights are granted to a group previously left out, the common-enemy power politics is strictly zero sum, specifically intended to reduce the power of the privileged and redistribute it to designated “victim groups.” Certain demographic categories and combinations of such categories are deemed to include greater victims than others (the result has been characterized by many different authors as the “oppression Olympics”; see Chua 2018; Lilla 2017). The members of these victim groups are all oppressed, to varying degrees, depending upon their demographic status profile, by the same common enemy (the white, heterosexual male). Instead of seeking social and cultural integration for particular victim groups, common-enemy identity politics wants to give priority to certain groups, especially in the contexts of politics and argumentation. Our focus will be on argumentation because the nonuniversality of common-enemy identity politics has the effect of magnifying myside bias and shutting down intellectual discussion.

So strange is the modern inversion of the “liberal” view that Stanovich points to survey research analyses by Zach Goldberg (2019), who “found that ‘white liberals recently became the only demographic group in America to display a pro–out-group bias—meaning that among all the different groups surveyed, white liberals were the only one that expressed a preference for other racial and ethnic communities above their own.’” White liberals as a group are now unique in being biased in favor of other races, based solely on raw skin color.

As I discussed in a previous essay, this sort of common enemy identity politics has significant detrimental effects on young people’s well-being, by inculcating within them a false notion that they have little power over their own lives (when they do have such power) and that they are instead living at the mercy of vague, external forces. But common enemy identity politics also reinforces people’s tendency to adopt myside reasoning. As Stanovich writes:

Common-enemy identity politics thus inflates myside bias in two ways. By encouraging people to view every issue through an identity lens, it creates the tendency to turn simple beliefs about testable propositions into full-blown convictions (distal beliefs) that are then projected onto new evidence. Although our identity is central to our narrative about ourselves, and many of our convictions will be centered around our identities, that doesn’t mean that every issue we encounter is relevant to our identities. Most of us know the difference and do not always treat a simple testable proposition as if it were a conviction. But identity politics (from now on, it will be clear that I am talking about the common-enemy version) encourages its adherents to see power relationships operating everywhere, and thus to enlarge the class of opinions that are treated as convictions. Then it deems the convictions of those from designated victim groups as something they can win an actual intellectual argument with by asserting their “official” victim status when disagreement comes their way. Students thus get used to framing all arguments from the standpoint of their respective identity groups (or combinations of groups). In universities, professors always know what is coming when they hear “Speaking as an X”—the framing of the argument as it looks from a particular demographic category. This stratagem, from the professor’s standpoint, sets a classroom discussion back a mile—immediately subverting the cognitive styles that the professor has been trying to develop all term (of reliance on logic and empirical evidence; use of operationalized terms; use of triangulated perspectives). Common-enemy identity politics has a particular method of valuing and devaluing arguments. That method is not at all based on the logical or empirical content of the argument; rather, it is based on the position of the source of the argument in the oppression hierarchy … By this reasoning, your arguments count for more if you have earned a higher medal in the victim Olympics … The critical feature of common-enemy identity politics that makes it strikingly different from the common-humanity identity politics of Martin Luther King Jr. is its mission: it intends not to restore equality, but to invert power relations.

Indeed, as I’ve written previously:

[Ibram X.] Kendi … maintains “The most threatening racist movement is not the alt right’s unlikely drive for a White ethnostate but the regular American’s drive for a ‘race-neutral’ one.” In Kendi’s perverse view, celebrating Martin Luther King Jr’s colorblind vision for America is a more threatening concept than white supremacy. How to explain the appeal of this perverse view among many of America’s elites? It starts with understanding that it is Kendi’s view, not “the regular American’s drive for ‘race-neutrality,” that is rooted in racist appeal. As Andrew Sullivan said recently in an interview, Kendi and [Robin] DiAngelo’s new form of racism appeals to the very same tribal sense to which older forms of racism appeal: “[Wokeness is] also much more conducive to human nature to see people in terms of groups rather than individuals … We are essentially tribal. And so what wokeness appeals to, in the way that the far right also appeals, it appeals to tribalism, and tribalism in its crudest sense of being able to identify people instantly as a member of your tribe or another tribe … So of course it’s likely to be more successful when you combine it with a form of moral rightousness as well. To tell people you can be tribalists and moral at the same time is an incredibly attractive way of life. To be able to see a white male and know instantly that person is part of the problem, before you even talk to them, is hugely rewarding … Liberalism, the achievement of seeing the individual independently of his or her group, is hard. It’s counter-intuitive, and so it’s always on the defensive in many ways. And whether it’s a sort of tribal right-wing racism or whether it’s a tribal left-wing neo-racism, they both come more naturally to humans than liberal discipline.”

Stanovich writes that

identity politics turns testable propositions into convictions by making virtually everything of sociocultural substance about an adherent’s identity. Because, if it is about your identity, it is always going to be a conviction, and this will magnify the myside bias you display in just about anything you talk about … [W]hat students should be learning at the university is how to decouple arguments from irrelevant contexts and irrelevant personal characteristics. A good university education teaches students to make these decoupled stances a natural habit. Instead, identity politics turns back the clock some 100 years on our notion of the purpose of a university education and specifically encourages students to take stances that assign unchangeable demographic characteristics additional weight in the intellectual fray … “The students who invoke this idea,” [Anthony] Kronman (2019, 115) notes, “didn’t invent it themselves. They are following the lead of the faculty, who ought to know better—who turned Socrates on his head by inviting their students to defer to the power of private experience rather than working to judge it in a disinterested light.”

Common enemy identity politics is especially harmful when taught in college, because it subverts the fundamental mission of universities, which is to encourage students to seek truth, not to automatically affirm their preexisting notions of identity:

Miserly cognitive processing arose for sound evolutionary reasons of computational efficiency, but that same efficiency will guarantee that perspective switching (to avoid myside bias) will not be the default processing action because, as we have known for some time, it is cognitively demanding to process information from the perspective of another person (Gilbert, Pelham, and Krull 1988; Taber and Lodge 2006). Thus we must practice the perspective switching needed to avoid myside bias until it becomes habitual. But identity politics prevents this from happening by locking in an automatized group perspective, by contextualizing based on preapproved group stances, and by viewing perspective switching through decoupling as a sellout to the hegemonic patriarchy … As a monistic ideology (Tetlock 1986), where all values come from a single perspective, identity politics entangles many testable propositions with identity-based convictions. It fosters myside bias by reversing Kahan’s (2016) prescription—by transforming positions on policy-relevant facts into badges of group-based convictions. One of the most depressing social trends of the last few decades has been universities becoming proponents of identity politics—a doctrine that attacks the heart of their intellectual mission.

As Stanovich writes, “If myside bias is the fire that has set ablaze the public communications commons in our society, then identity politics is the gasoline that will turn a containable fire into an epic conflagration.”

So how did a culture that came to embrace Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision of a colorblind society that evaluated people and policies independently of their immutable characteristics come to adopt a diametrically opposed vision, namely one that evaluates people and policies explicitly on the basis of race and other immutable characteristics, within a couple generations? It could not have been due to any sort of logical, syllogistic reasoning. Instead, it was influenced by cultural elites who lead universities and political parties. And as we will explore in the next essay, such elite institutions are particularly subject to myside bias.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5.