Sources of Bias in Reasoning – Part 2

Practical and tribal reasons for “myside” thinking.

In the previous essay we started to explore Keith Stanovich’s book, The Bias That Divides Us: The Science and Politics of Myside Thinking, in which he discusses “myside bias,” namely our tendency to “evaluate evidence, generate evidence, and test hypotheses in a manner biased toward our own prior beliefs, opinions, and attitudes.”

There are additional, practical, reasons for myside bias, including those as mundane as “making life easier for us to bear.” As Stanovich writes:

Richard Foley (1991) describes the case of a person, a man, say, believing that his lover is faithful despite substantial evidence to the contrary. Because believing that the lover is faithful satisfies a number of his desires (that the relationship continue; that domestic living arrangements not be disrupted), it would not be surprising that, were you in such a situation, you may “find yourself insisting on higher standards of evidence, and as a result it may take unusually good evidence to convince you of infidelity” (Foley 1991, 375). Although, without knowing that there were goals or desires involved, an outside observer might view the criterion for belief as irrationally high, consideration of epistemic and instrumental goals would make the setting of a high epistemic criterion here seem rational.

Beyond wanting to simply make life easier for ourselves, myside bias can occur because we don’t want to offend the tribe with whom we’ve come to identify, either as a result of social bonds or evolutionary processes. As Paul Bloom writes in his book Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion:

[O]ther biases have causes that go deeper than empathy. We are constituted to favor our friends and family over strangers, to care more about members of our own group than people from different, perhaps opposing, groups. This fact about human nature is inevitable given our evolutionary history. Any creature that didn’t have special sentiments toward those that shared its genes and helped it in the past would get its ass kicked from a Darwinian perspective; it would falter relative to competitors with more parochial natures. This bias to favor those close to us is general -- it influences who we readily empathize with, but it also influences who we like, who we tend to care for, who we will affiliate with, who we will punish, and so on. Its scope is far broader than empathy.

As Stanovich puts it, regarding our socialization:

The social domain is one that often makes epistemic accuracy subordinate to instrumental rationality. Group cohesion often necessitates that group members hold beliefs that exhibit considerable inertia. Being a good group member almost by definition requires that the members display considerable myside bias when encountering ideas that contradict group beliefs. It is almost always the case, however, that the costs of the inaccuracies introduced into a particular member’s belief network by that myside bias are outweighed by the considerable benefits provided by group membership … Thus group identities are a key source of myside bias.

Just as sports fans often find themselves siding with the referees when they make a call in favor of their favorite team (even when the replay shows the referees clearly got it wrong) we all have a tendency to go along with what “our team tribe” thinks is best:

According to Kahan (2013, 2015), [identity protective cognition] arises when we have a defining commitment to an affinity group that holds certain beliefs as central to its social identity. The ebb and flow of the information that we are exposed to may contain evidence that undermines one of these central beliefs. If we accurately update our beliefs on the basis of this evidence, we may subject ourselves to sanctions from a group that defines our identity. Hence we will quite naturally have a myside bias toward the group’s central beliefs—adopting a high threshold for accommodating disconfirming information and a low threshold for assimilating confirming information … Many of our communications are not aimed at conveying information about what is true (Tetlock 2002). Instead, as signals to others and sometimes signals to ourselves, they are functional communications because, when sent to others, they bind us to a group that we value, and, when sent to ourselves, they serve motivational functions.

One such function is “virtue signaling,” whereby the point of something we say is not the truth of it, but that it communicates to others in our tribe that “we’re with them.” For example:

Nozick (1993) points to several antidrug measures that may fall in this category. In some cases, evidence has accumulated to indicate that an antidrug program does not reduce actual illegal drug use, but the program is continued because it has become the symbol of our concern for stopping such illegal use. In the present day, many actions signaling a concern for global warming have this logic (their immediate efficacy is less important than the meaning of the signal being sent by the signaler).

And just as the internet has dramatically expanded our ability to communicate to others (a good thing), it has also dramatically expanded our ability to virtue signal, leaving many to find false comfort in a vast population of fellow virtue signallers making few (if any) substantive arguments:

Many recent commentators have argued that the same kind of commons dilemma now surrounds the use of social media and the Internet in our society. As the Silicon Valley entrepreneur Roger McNamee (2019, 163) notes: “Most users really like Facebook. They really like Google. There is no other way to explain the huge number of daily users. Few had any awareness of a dark side, that Facebook and Google could be great for them but bad for society.”

We’ve all seen on social media how some people often virtue signal by announcing their views (or insulting others with different views) but in either case they’re not using argument. And when argument isn’t involved, emotion takes its place. And when emotion is directed in a biased manner it can skew feelings of empathy. Bloom cites this study involving European soccer fans to make the point:

Empathy is also influenced by the group to which the other individual belongs -- whether the person you are looking at or thinking about is one of Us or one of Them. One European study tested male soccer fans. The fan would receive a shock on the back of his hand and then watch another man receive the same shock. When the other man was described as a fan of the subject’s team, the empathic neural response -- the overlap in self-other pain -- was strong. But when the man was described as a fan of the opposing team, it wasn’t.

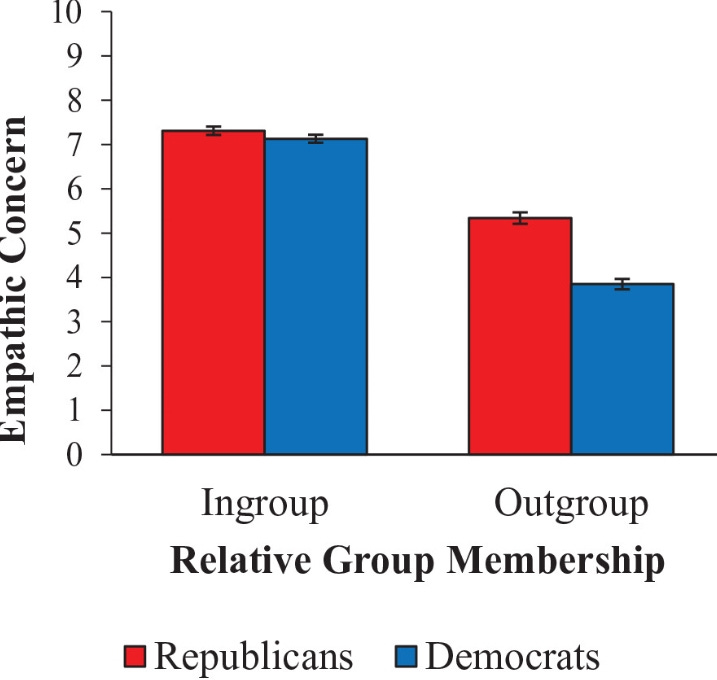

Some research has also shown that empathy can lead to such significant associations with the “in-group” a person sympathizes with that aggression results against the out-group, even without actual provocation or injustice. And researchers have found that people who score high on the empathy scale are more likely to support efforts by protesters to silence a speaker from the opposing political party and that they are also more likely to be amused by reports that the protesters injured a supporter of the speaker. The researchers found that “While those at the lower end of the empathic concern scale do not distinguish between the two types of speakers, those at the higher end are significantly more likely to want to stop the speech when the speaker is from the opposite party. More specifically, for an individual who is one standard deviation above the mean of empathic concern, the desire for censorship increases from 3.22 (on the five-point scale) to 3.77 … These findings then fit with our expectations that dispositional empathy serves to exacerbate partisan bias.”

As Bloom writes, when bias creeps in, we can’t even trust that our feelings of empathy are keeping us “moral.” As Bloom writes:

[R]eactions to others, including our empathic reactions, reflect prior bias, preference, and judgment. This shows that it can’t be that empathy simply makes us moral. It has to be more complicated than that because whether or not you feel empathy depends on prior decisions about who to worry about, who counts, who matters -- and these are moral choices.

Indeed, a 2025 study found that across all four studies conducted, participants consistently showed lower empathy for political outgroup members than for ingroup or neutral targets. However, this bias was not symmetrical. Liberals exhibited significantly less empathy for conservatives than conservatives showed for liberals. In Study 1, this asymmetry was driven by liberals’ stronger negative judgments of conservatives’ morality and likability. Conservatives’ empathic responses remained relatively stable regardless of the target’s political affiliation. The researchers “found a consistent asymmetry in this empathy bias. In each of our four studies (and in aggregate across studies) conservatives showed more empathy for liberals than liberals showed for conservatives.”

Social media, the traffic of which is often driven by dramatic visuals and images of specific people and events, can also obscure the “big picture.” As Bloom writes:

If our concern is driven by thoughts of the suffering of specific individuals, then it sets up a perverse situation in which the suffering of one can matter more than the suffering of a thousand. To get a sense of the innumerate nature of our feelings, imagine reading that two hundred people just died in an earthquake in a remote country. How do you feel? Now imagine that you just discovered that the actual number of deaths was two thousand. Do you now feel ten times worse? Do you feel any worse? I doubt it. Indeed, one individual can matter more than a hundred because a single individual can evoke feelings in a way that a multitude cannot. Stalin has been quoted as saying, “One death is a tragedy; one million is a statistic.” And Mother Teresa once said, “If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.”

When such feelings motivate public policy positions, the result may feel good to individuals, but it can be a disaster for society as a whole. As Stanovich writes, a “tragedy of the science communications commons” is demonstrated by:

(Kahan 2013; Kahan, Peters, et al. 2012; Kahan et al. 2017) [who show] the conundrum that results from a society full of people gaining utility from rationally processing evidence with a myside bias, but ultimately losing more than they gain because society overall would be better off if public policy were objective and based on what was actually true. When everyone processes with a myside bias, the result is a society that cannot converge on the truth.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at evidence regarding the very origins of our convictions.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5.

"As Bloom writes, when bias creeps in, we can’t even trust that our feelings of empathy are keeping us 'moral.'"

IMO, people often conflate 'empathy' with the voice of their conscience, which voice they tacitly assume is infallible.

But one's conscience is not one's moral guide. It is rather one's co-conspirator.

"If our concern is driven by thoughts of the suffering of specific individuals, then it sets up a perverse situation in which the suffering of one can matter more than the suffering of a thousand."

Yes. This is an observation that I've seen attributed to Stalin: "One death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic."