Scattered Entries

Today’s essay is a collection of shorter thoughts on varied subjects …

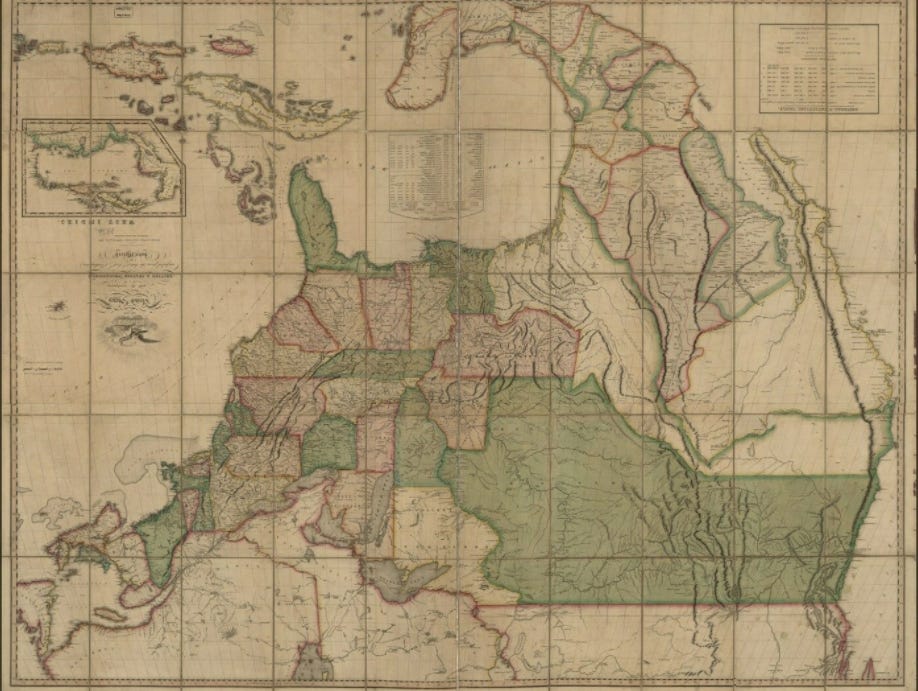

(Note: image above is intentionally upside down, showing how Mexican and American immigration situations were reversed in the early 1800’s.)

How Mexico Addressed Its Own Immigration Crisis in the Early 1800’s

I posted a previous essay on the wage-depressing effects of illegal immigration, and I want to make an additional comment here on how Mexico addressed its own immigration problem back in the early 1800’s -- when it was Americans who were flooding over Mexico’s northern border. These Americans were known as Texians because they settled in Coahuila y Texas, a part of Mexico established by the Mexican Constitution of 1824. At first these American settlers were welcomed on the theory that they’d boost Mexico’s economy, but then Mexican authorities started to change their minds about the benefits of this mass migration.

In his book “The Texas Revolution and the U.S.-Mexican War: A Concise History,” Paul Calore writes:

With all the attention [America] was giving to this desolate corner of Mexico it didn’t take long before government officials in Mexico City became quite concerned over the large influx of Americans coming into Mexico. Ironically, what was once considered a good way to improve the economy and the well-being of the country, especially in Coahuila y Texas, was now viewed with much trepidation. Their paranoia and suspicion led them to believe that one day the United States might attempt a hostile takeover to acquire northern Mexico … To buttress their argument, they claimed the Texians consistently refused to assimilate into the Mexican culture, continued their old customs, built their own schools, spoke their own language, and traded mostly with the United States, behavior that only exacerbated the bitter enmity between the Texians and the Mexicans. (“Texian” was the term generally used from 1821 to 1836 to identify an Anglo-American settler in the Texas colonies.) The more the Texians demonstrated their ability to be self-sufficient, politically stable, and culturally independent from the rest of the state, the more attention the colonies attracted from the Mexican government. Furthermore, the government suspected the Texians were becoming increasingly reluctant to give up their American citizenship to live in Mexico. In fact, the concern over the growing population of Anglos in the settlements and their apparent autonomy was now coming to a head. The mounting frustration over a growing population of Anglos and their apparent lack of assimilation forced the new president to take direct action. As a consequence, Pres. Anastasio Bustamante ordered Gen. Manuel de Mier y Terán to review the various Mexican colonization laws that were instituted from 1823 to 1825. Terán’s final report resulted in a series of some 18 new laws or articles issued on April 6, 1830, that were principally aimed at the settlers living in Coahuila y Texas … By the end of October of 1835 the Texians had become an enormous irritant to Santa Anna. Once welcomed with open arms as citizens of the homeland, they were now considered outside agitators that had to be quickly dealt with … Santa Anna was also reminded that the Texians had made a total mockery of the Mexican law against slavery and about their arrogant insistence to remain autonomous, their obvious unwillingness to assimilate, and their total disrespect for the law prohibiting illegal conventions … Besides the total lack of respect for the Mexican culture, the growing population of Americans in Texas also weighed heavily on Santa Anna’s mind.

Sound familiar? The Mexican government thought too many Americans were coming to their country, refusing to assimilate to Mexican norms and culture, living in communities and interacting with institutions isolated from the rest of Mexican society, and refusing to speak Spanish. As Calore writes, the Mexican government responded by, yes, closing the border:

Another [Mexican] law prohibited any further immigration from the United States into Coahuila y Texas, an outrageous ruling that infuriated the Texians. The wording of this law was such that it prohibited the settlement of immigrants in any territory that was adjacent to their native country, an indirect reference to the United States and the Texas border.

But that approach didn’t work, at least in part because Mexico didn’t build any physical barriers to entry:

Even though [General] Bustamante had imposed a restriction on immigration from the United States, thousands still poured across the border. It was an edict the administration found difficult to enforce and as a result it was something the Mexicans lost complete control of. By conservative estimates, in 1834 the number of Anglos living in the region was at least four times as great as that of the native Mexicans. The Mexican president, extremely outraged over these developments, abruptly left the comforts of his hacienda in Veracruz and returned to Mexico City.

The only solution at that point was for the Mexican government to use its army to eject the illegal aliens:

After formally placing his vice president, Gen. Miguel Barragán, in charge of the executive department, Santa Anna was faced with the enormous task of piecing together an army he could depend upon to eject the Americans from Mexico once and for all. The remote northern provinces were once an area receiving scant attention; now it was about to receive the full wrath of the government’s interest. Santa Anna’s mind was made up. He was fed up with the Americans and was going to show these cocky and arrogant Texians who the real boss was. On December 5, 1835, Santa Anna and Gen. Vicente Filisola arrived in San Luis Potosí to begin organizing an all-out advance northward toward Béxar and the nearby mission called the Alamo.

That military adventure led to the independence of Texas, and later to its joining the United States. And the rest is history, which, some might say, is repeating itself in many ways today -- but now with the roles reversed.

Another Reason the Columbian Exchange was Awesome

In a previous essay I described the massive (and overwhelmingly beneficial) influence Columbus’ connecting the two hemispheres had on world progress. New research amplifies that conclusion by finding that the introduction of the potato worldwide led to a dramatic reduction in world conflict. The authors of the study, “The Long-run Effects of Agricultural Productivity on Conflict: 1400-1900,” write:

This paper provides evidence of the long-run effects of a permanent increase in agricultural productivity on conflict. We construct a newly digitized and geo-referenced dataset of battles in Europe, the Near East, and North Africa from 1400–1900 ce and examine variation in agricultural productivity due to the introduction of potatoes from the Americas to the Old World after the Columbian Exchange. We find that the introduction of potatoes led to a sizeable and permanent reduction in conflict … Potatoes are native to South America and came to the Eastern Hemisphere via Europe during the Columbian Exchange. Upon arrival in the 16th Century, they were initially seen as an exotic curiosity rather than an edible crop. One of the first accounts of potatoes being widely cultivated is from England in the 1690s, where potatoes were used as a supplement to bread. By the late-18th century, potatoes had become an important field crop in countries such as France, Austria, and Russia. Once Europeans began cultivating the potato, it spread fairly rapidly to other parts of the Western Hemisphere by European mariners who carried it to ports across Asia and Africa … Potatoes provide many more calories per acre of land than pre-existing staple crops such as wheat, rice or barley. They are also rich in micronutrients and lack only vitamins A and D. In fact, humans can have a healthy diet from consuming only potatoes, supplemented with only dairy, which contains the two vitamins not provided by potatoes. Potatoes are also more resistant to cold weather than existing staple crops. Thus, the availability of potatoes allowed Europeans to increase the productivity of existing agricultural land as well as to bring marginal pieces of land in colder climates into agricultural production … Our estimates show that the introduction of potatoes led to a significant reduction in the incidence of conflict. The finding is robust to the use of differently sized grid cells, different time periods, more or less flexible estimation strategies, and flexibly controlling for a host of observable grid-cell level characteristics. Hazard estimates indicate that the effects on conflict incidence are primarily due to a reduction in the probability of conflict onset rather than a decline in duration (i.e., the probability of conflict offset). We find no evidence that the estimated effects arise because potatoes provide insurance against cold winters.

New 1619 Project Book

We visited historic Jamestown over the Thanksgiving break, and while I was in the giftshop I came across a new book titled The 1619 Project: Born on the Water, co-authored by the creator of the 1619 Project, Nikole Hanna-Jones. It’s a short children’s story about a girl who researches her family history and how her ancestors were enslaved. It contains this page:

Some people in Africa were enslaved directly by white people, but that was the exception. As mentioned in a previous essay, Henry Louis Gates Jr., the chair of Harvard’s Department of African and African American Studies, once directly urged Hannah Jones to acknowledge the dominant role of the black African warlords who kidnapped other blacks for the slave trade. “Talk about the African world and the slave trade,” Gates urged Hanna-Jones (at the 1:42 minute mark), “This is something black people don’t want to talk about. But … 90 percent of the Africans who ended up here were the victims of imperial wars – wars between imperial states in Africa – when Africans were capturing Africans and selling them to Europeans along the coast. This has got to be full disclosure. And we’ve got to talk about that.”

Perhaps that will happen in Hannah-Jones’ next book.

Guns on the Defensive

Lots of people are worried about the large number of privately held guns in America today that are used in the commission of crimes. But much less remarked upon is the apparently large number of times guns are used to protect innocent people from criminals. As researcher John Lott writes:

While Americans know that guns take many innocent lives every year, many don’t know that firearms also save them … [N]early 1,000 instances [were] reported by the media so far this year in which gun owners have stopped mass shootings and other murderous acts, saving countless lives. And crime experts say such high-profile cases represent only a small fraction of the instances in which guns are used defensively … Americans who look only at the daily headlines would be surprised to learn that, according to academic estimates, defensive gun uses — including instances when guns are simply shown to deter a crime — are four to five times more common than gun crimes, and far more frequent than the roughly 20,000 murders or fewer each year, with or without a gun … The U.S. Department of Justice’s National Crime Victimization Survey indicates that around 100,000 defensive gun uses occur each year -- an estimate that, though it may seem like a lot, is actually much lower than 17 other surveys. They find between 760,000 defensive handgun uses and 3.6 million defensive uses of any type of gun per year, with an average of about 2 million. The difference between these surveys arises from the screening questions. The National Crime Victimization Survey first asks a person if they have been a victim of a crime. Only respondents who answer “yes” are asked if they have ever used a gun defensively. In contrast, the other surveys screen respondents by asking if they have been threatened with violence. That produces more self-acknowledged defensive gun users, since someone who successfully brandished a gun is less likely to self-characterize as a crime victim. Survey data indicate that in 95% of cases when people use guns defensively, they merely show the gun to make the criminal back off. Such defensive gun uses rarely make the news, though a few do.

And the large number of privately held guns in America has a larger geopolitical benefit to America as well. As Tim Marshall writes in Prisoners of Geography:

[A]nyone stupid enough to contemplate invading America would soon reflect on the fact that it contains hundreds of millions of guns, which are available to a population that takes its life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness very seriously. In addition to the formidable U.S. armed forces, there is the National Guard, state police, and, as we’ve seen recently, an urban police force that can quickly resemble a military unit. In the event of an invasion, every U.S. Folsom, Fairfax and Farmerville would quickly resemble an Iraqi Fallujah.