Columbus (and Columbus Day) from a Distance

Gauging impact from a time distance, away from contemporary politics.

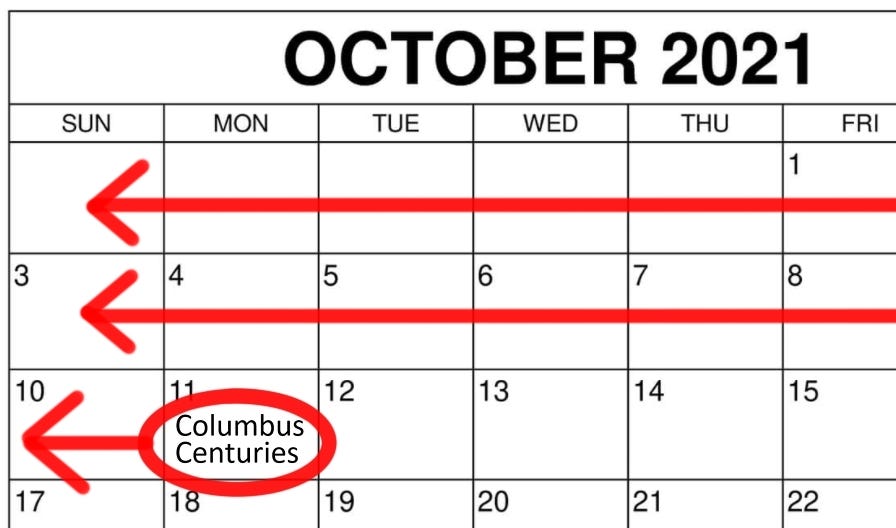

Columbus Day has become dominated by contemporary ideological arguments. So it may be best to consider Columbus’ impact a week or so after Columbus Day, to get a little distance from the politics of the day itself. That’s appropriate, since a full appreciation of Columbus’ impact on the world involves an appreciation of the vast global changes his efforts spurred over many centuries.

Columbus sailed west in large part because, at the time, Islamic rulers in the East had cut off European trade to Asia, thereby incentivizing Europeans to seek trade routes to Asia by traveling in the other direction, around the world. As described by historian Timothy Winegard in his great book “The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator”:

From its epicenter in Turkey, the Islamic Ottoman Empire expanded across the Middle East, the Balkans, and eastern Europe during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and closed the Silk Road to Christian traders and European access to the Asian market … [T]he great powers of Europe sought to reopen this crucial commercial lifeline by circumventing the increasingly vast and combative Ottoman Empire. After six years of pestering the monarchies of Europe for funding, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain finally relented and agreed to back the first voyage of … Cristobal Colon (as Columbus was known in 1492) to reestablish trade with the Far East.

When Columbus and his relatively small crew encountered already inhabited lands, of course, they were in no position to dictate anything to the overwhelmingly larger numbers of indigenous populations they found in the Americas. So Columbus and his crew mostly traded and bartered for things, including slaves that had originally been enslaved by the indigenous populations themselves. Spanish explorers who followed soon after Columbus even rescued many of the local tribes from another warlike, vicious, and cannibalistic tribe called the Caribs. (While some have disputed Columbus’ own description of the Carib tribe, its existence seems to have been confirmed recently by researchers studying skulls in the region.) As Martin Dugard describes in his book “The Last Voyage of Columbus:”

[Alonso de] Ojeda … led his men into battle against the Carib Indians. Although their armor was hot to the touch and made them sweat profusely in the equatorial sun, it protected the Spanish from the spears and arrows tipped with sharpened tortoiseshells that were fired in their direction. Ojeda suffered only one casualty that summer. The Caribs were infamous, even to the Spanish, who knew of them from Columbus’s voyages. As one Spanish observer wrote: “They travel 150 leagues to make war in their canoes, which are small fustas hewn out of a single tree. These people raid the other islands and carry off all the women they can take, especially the young and beautiful, whom they keep as servants and concubines. They had carried off so many that in fifty houses we found no males and more than twenty of the captives were girls. These women say they are treated with a cruelty that seems incredible. The Caribs eat the male children they have by them, and only bring up the children of their own women. And as for the men they are able to capture, they bring those who are alive home to be slaughtered and eat those who are dead on the spot. They say that human flesh is so good there is nothing like it in the world.” By defeating the Caribs in battle, the Spaniards temporarily ended that threat. The other local tribes showed their overwhelming gratitude with an outpouring of warmth and generosity, and Ojeda took advantage of this appreciation by sending twenty-seven of his men into the jungle to search for gold. It was a journey they would never forget. For nine days those men lived an elaborate tropical fantasy. They encountered nothing but friendly tribes, all beside themselves with joy that the Caribs had been vanquished. Each evening these tribes assembled elaborate feasts, complete with games and tribal dancing. At the end of the night, a wife or daughter was sent to sleep with each man. It was with deep regret—and no gold—that they returned to the boredom and austerity of shipboard life.

Romantic interests apparently went both ways. Indeed, the interest local women showed in Columbus’ crew contributed to subsequent friction with the indigenous populations. As Dugard writes:

The teenagers who made up such a large part of the crews and who had left Spain as mere boys in May had become grown men by November. They sneaked off the ships at night to meet up with willing Indian women on shore, which only increased local hostility toward the Spanish … [In another instance,] Quibian [a local chief] sent word that Bartolomé [Columbus’ brother] must halt, warning them against entering the palace. “He did this to keep the Christians from seeing his wives,” Fernando theorized, “for the Indians are very jealous.” Columbus’s sailors had routinely sneaked away from the ship to have relations with Indian girls. Quibian’s outrage about that intercourse was a prime reason he wanted the Spanish dead.

Ultimately, it was the indigenous populations of the Americans who subsequently perished in vast numbers, but the cause wasn’t European violence, let alone false claims of “genocide.” The cause was the spread of disease in a time when the causes of disease, and the genetic susceptibility of certain previously unexposed populations to diseases new to them, wasn’t understood.

As Winegard writes in his book “The Mosquito”:

The mosquito has killed more people than any other cause of death in human history. Statistical extrapolation situates mosquito-inflicted deaths approaching half of all humans that have ever lived. In plain numbers, the mosquito has dispatched an estimated 52 billion people from a total of 108 billion throughout our relatively brief 200,000-year existence. Yet, the mosquito does not directly harm anyone. It is the toxic and highly evolved diseases she transmits that cause an endless barrage of desolation and death … Of the estimated 100 million indigenous inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere in 1492, a population of roughly 5 million remained by 1700. Over 20% of the world’s population had been erased. The mosquito, along with other diseases such as smallpox, was culpable of genocidal extermination.

So it just so happened that, as a result of much greater genetic resistance to certain diseases, “The exchange of disease was a one-way street—Old World to New World—with perhaps one exception.” (That one exception was syphilis. As Winegard continues, “The first European outbreak of the disease [syphilis] appears to have occurred in Naples, Italy, in 1494 shortly after the return of Columbus from his first voyage. Whether this is a connection, or a coincidence, is still hotly debated and is the subject of ongoing academic research. Within five years, the disease had slept its way across Europe, with each nation blaming its neighbor. In 1826, Pope Leo XII banned the condom because it prevented debauched people from acquiring syphilis, which he viewed as their necessary and divine punishment for their immorality and sexual transgressions.” Winegard also adds that Columbus “died in 1506 of ‘reactive arthritis,’ heart failure usually associated with syphilis.”)

Regarding the diseases Columbus and his followers unknowingly brought to the Americas, Winegard summarizes:

Spanish cruelty, known as the Black Legend [] did not play the main role in the cataclysmic demise of local populations. Across the Spanish dominion, malaria, smallpox, tuberculosis, and eventually yellow fever were the paramount killers. As a result, however, the mosquito, and the Spanish colonists to a much lesser extent, had wiped out the prospect of a substantial, self-reproducing [local] Taino labor force. As both Europeans and indigenous peoples succumbed to malaria and other diseases, alternative labor was needed to fuel the lucrative production of tobacco, sugar, coffee, and cocoa. The African slave trade [explored here in a previous Big Picture entry] was caught up in the whirlwinds of the Columbian Exchange … Yes, Europeans came, but they did not conquer indigenous peoples and the Americas by themselves. The Anopheles and Aedes mosquitoes came and conquered.

As John Ellis writes in A Short History of Relations Between Peoples: How the World Began to Move Beyond Tribalism:

It’s perfectly true that native populations were devastated by common diseases brought by contact with Europeans, because they had never been able to develop the immunity to those diseases that Europeans had. But a severe short-term medical crisis of this kind was inevitable. The long-term medical consequence of contact with the known world, however, would be quite another matter. Modern medicine has doubled the life-spans of the discovered peoples, and it has greatly improved their health and well-being.

Yet along with the tragic loss of huge numbers of indigenous people to disease, there came a stunning new exchange of foods from the Old World to the New World, and vice versa (in what became known as the Columbian Exchange), allowing for the growing of foods in new places all around the world that led to dramatic increases in population. The Columbian Exchange also brought better methods of farming to the Americas, and the introduction of bees for pollination, and a resulting explosion of food production. As Winegard writes:

On the eve of the Columbian Exchange and the imminent European onslaught, only 0.5% of the land east of the Mississippi River in the United States and Canada was under cultivation. For European countries, this figure ranged from 10 to 50%! … With the introduction of commercial agriculture and dam building, European settlers unwittingly created a toxic environment for themselves by establishing ideal mosquito-breeding habitats … [However,] [a]long with mosquitoes, English settlers also introduced honeybees to the Americas. Feral hordes quickly began the mass pollination of indigenous plants and also aided the bounty of European farms and orchards. Currently, 35% of foods consumed in the United States are derived from honeybee pollination.

As David Landes writes in The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor:

The Opening [between the Old and New Worlds] brought first an exchange— the so- called Columbian exchange— of the life forms of two biospheres. The Europeans found in the New World new peoples and animals, but above all, new plants— some nutritive (maize [Indian corn], cocoa [cacao], potato, sweet potato), some addictive and harmful (tobacco, coca), some industrially useful (new hardwoods, rubber). These products were adapted diversely into Old World contexts, some early, some late (rubber does not become important until the nineteenth century). The new foods altered diets around the world. Corn, for example, became a staple of Italian (polenta) and Balkan (mamaliga) cuisines; while potatoes became the main starch of Europe north of the Alps and Pyrenees, even replacing bread in some places (Ireland, Flanders). So important was the potato that some historians have seen it as the source and secret of the European population “explosion” of the nineteenth century. In return, Europe brought to the New World new plants— sugar, cereals; and new fauna— the horse, horned cattle, sheep, and new breeds of dog. Some of these served as weapons of conquest; or like the cattle and sheep, took over much of the land from its inhabitants.

And the Colombian Exchange also led to an exchange of spices. As Landes writes:

People of our day may wonder why pepper and other condiments were worth so much to Europeans of long ago. The reason lay in the problem of food preservation in a world of marginal subsistence. Food supply in the form of cereals barely sufficed, and it was not possible to devote large quantities of grain to animals during long winters, excepting of course breeding stock, draft animals, and horses. Hence the traditional autumnal slaughter. To keep this meat around the calendar, through hot and cold, in a world without artificial refrigeration, it was smoked, corned, spiced, and otherwise preserved; when cooked, the meat was heavily seasoned, the better to hide the taste and odor of spoilage. Hence the paradox that the cuisine of warmer countries is typically “hotter” than that of colder lands— there is more to hide. Condiments brought a further dividend. The people of that day could not know this, but the stronger spices worked to kill or weaken the bacteria and viruses that promoted and fed on decay. Tabasco and other hot sauces, for instance, will render infected oysters safer for human consumption; at least they kill microorganisms in the test tube. Spices, then, were not merely a luxury in medieval Europe but also a necessity, as their market value testified.

Landes also describes the importance of the Columbian exchange this way:

The Industrial Revolution made some countries richer and others (relatively) poorer; or more accurately, some countries made an industrial revolution and became rich; and others did not and stayed poor. This process of selection actually began much earlier, during the age of discovery. The Opening brought first an exchange— the so-called Columbian exchange— of the life forms of two biospheres. The Europeans found in the New World new peoples and animals, but above all, new plants— some nutritive (maize [Indian corn], cocoa [cacao], potato, sweet potato), some addictive and harmful (tobacco, coca), some industrially useful (new hardwoods, rubber). These products were adapted diversely into Old World contexts, some early, some late (rubber does not become important until the nineteenth century). The new foods altered diets around the world. Corn, for example, became a staple of Italian (polenta) and Balkan (mamaliga) cuisines; while potatoes became the main starch of Europe north of the Alps and Pyrenees, even replacing bread in some places (Ireland, Flanders). So important was the potato that some historians have seen it as the source and secret of the European population “explosion” of the nineteenth century. In return, Europe brought to the New World new plants— sugar, cereals; and new fauna— the horse, horned cattle, sheep, and new breeds of dog. Some of these served as weapons of conquest; or like the cattle and sheep, took over much of the land from its inhabitants. Worse yet by far, the Europeans and the black slaves they brought with them from Africa carried nasty, microscopic baggage: the viruses of smallpox, measles, and yellow fever; the protozoan parasite of malaria; the bacillus of diphtheria; the rickettsia of typhus; the spirochete of yaws; the bacterium of tuberculosis. To these pathogens, the residents of the Old World had grown diversely resistant. Centuries of exposure within Eurasia had selected human strains that stood up to such maladies. The Amerindians, on the other hand, died in huge numbers, in some places all of them, to the point where only the sparsity of survivors and some happy strains of resistance enabled a few to pull through. Why the Eurasian biosphere was so much more virulent than the American is hard to say. Greater population densities and frequency of contagion? The chance distribution of pathogens? Where were the Amerindian diseases? Only one has come down to us— syphilis, which the French called the Italian disease, the Germans the French disease, and so on as it made its way from seaports to the rest of Europe.

The means of reducing the incidence of malaria, too, came with the spread of the scientific method. As Winegard continues:

Quinine and malaria are a perfect example of this unprecedented union and cross-pollination of extremely different, previously isolated, and evolutionarily distinct worlds kick-started by the voyages of Columbus. Quinine [discovered by Spanish Jesuits in Peru to be an effective malaria suppressant] was a New World treatment for an Old World disease.

And with the indigenous populations’ having overwhelmingly succumbed to disease, it was the Spanish explorers and those who followed them who repopulated the region, such that today the vast majority of Mexicans have at least partial Spanish ancestry and Mexicans of full or predominant Spanish ancestry make up about half of the population. So along with the plant seeds spread around the world by the Columbian Exchange, Columbus also planted the human seeds of today’s Latin American populations. It’s not surprising, then, that the tallest sculpture in North America is a monument to Christopher Columbus, completed in 2016. And it’s in Puerto Rico.

And while the unintentional loss of indigenous people to disease was tragic, it’s also worth remembering that also tragic were the intentional sacrificial killings occurring in the Aztec Empire before Columbus arrived. As Nigel Davies writes in Human Sacrifice: In History and Today:

The greatest recorded sacrifice of all time took place in 1487, in the reign of Ahuitzotl [an Aztec ruler], to inaugurate the Great Temple. The Emperor, together with two allied rulers and his leading official, led the way, accompanied by throngs of priests; both they and the victims were dressed as gods. The captives, duly painted and feathered, had formed into interminable lines that stretched along the main causeways into the city … The sacrifice lasted four whole days. When Ahuitzotl and his royal colleagues wearied of gashing open the victims’ breasts, the priests took up the knives in their place … In terms of sheer numbers slain, the Mexicans were in the top league, but shared the distinction with others … [I]t will be recalled that in Agbomey, an average year claimed five hundred lives, rising to a thousand when a king died, in a town whose population was barely 20,000 … [T]he Aztecs had to slay some five thousand people in a normal year, rising to ten thousand under special circumstances, such as the dedication of a major temple or the death of a monarch … Aztec texts [] go out of their way to extol the role of human sacrifice. Scarcely a a folio of the religious codices is without its decapitated heads, skulls, skeletal figures and sacrificial knives, if not bodies, from which spurts “the beautiful blood “ (chalchiuheztli) of the gods’ victims …”

David Landes, in his book The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Are Some So Rich and Some So Poor, writes the following regarding the main reasons for the fall of the Aztec and Inca Empires:

[T]he Aztec empire collapsed for deeper reasons. The most important lay in the very nature of tributary empires, which differ from kingdoms and nations by their ethnic diversity and want of sympathetic cohesion. The we/ they division separates rulers from ruled and one member group from another; not members from outsiders. Such units are necessarily an expression of naked power. They rest on no deep loyalty; enjoy no real legitimacy; extort wealth by threat of pain. So, although they have the appearance of might, it is only appearance, and the replacement of one gang of tyrants by another is often welcomed by common folk who hope against hope that a change will relieve their oppression. In reality, the brilliance of these constructs is but glitter; their apparent hardness a brittle shell. Aztec terror took the form of the industrialization of blood sacrifice. This is a touchy subject, which anthropologists and ideologues of indigenista have preferred to avoid or ignore, if not to excuse. Yet one cannot understand the strengths and weaknesses of the Aztec empire, its rise and fall, without dealing with this hate- provoking practice. Human sacrifice for religious purposes was general to the area (including Mayan lands to the south) and reflected a belief that the sun god in particular needed human blood for nourishment. Unfed, he might not rise again. Other gods also needed offerings: of babies and children, for example, to ensure the fertility of crops or an abundance of rain; the tears of the victims were a promise of water. Such symbolic gestures (perceived as acts of consubstantial nourishment) needed few victims. Adult flesh came primarily from capture in battle, and the victim was presented and told to think of himself as a hero in a noble cause: this is what we were born to. Some scholars have pretended that these heart and blood donors did think of themselves that way, but it should be noted that they needed a dose of tranquilizer before they could be persuaded docilely to climb the steep steps to the altar. The Aztec innovation was the work of a member of the royal family, Tlacallel, kingmaker and adviser to a series of emperors. This prince of darkness thought to impose and substitute for other, milder gods the Aztec tribal god Huitzilopochtli, the hummingbird of the south, a bloodthirsty divinity all wings and claws; and behind those beating wings, to make of the sacrificial cult a weapon of intimidation. Where once the sacrifice touched a handful, Tlacallel instituted blood orgies that lasted days and brought hundreds, then thousands, of victims to the stone, their hearts ripped out while still beating, their blood spattered and sprinkled on the idols, their bodies rolled down the steps and butchered to furnish culinary delicacies to the Aztec aristocracy. This last practice embarrasses politically correct ethnologists, who see in such descriptions of cannibalism a justification for foreign contempt and oppression. (It was certainly that for the conquistadors, who were disgusted when their Mexican hosts showed hospitality by saucing their guests’ food with the blood of victims sacrificed right before their eyes.) Some have tried to argue that the whole business of cannibalism is a myth, a Spanish invention. Others, ready to concede the anthropophagy, have pointed to occasional Spanish lapses— as though measures of desperation are comparable to institutionalized behavior; or have tried to argue that this was the only way for the Aztecs (or at least the aristocracy, who had a quasi- monopoly of human flesh) to get enough protein in their diet. The best one can say for such nonsense, especially as applied to the privileged members of Aztec society, is that it shows imagination. Aztec ceremonies also created a supply problem: where to get enough victims. In war? But that meant incessant fighting. In the prisons or among the slaves? But that meant an intensification of oppression and potential instability. With the connivance of the rulers of allied/ subject peoples? This was the device of the so- called flower wars, where aristocratic collaborators from other nations watched behind flower screens as the Aztecs staged simulated war games and jousts designed to produce prisoners for sacrifice before the hidden eyes of their own chiefs. For all its seeming power and glory, then, the Aztec empire was a house of feathers. Detested for its tyranny and riven with dissension, it was already in breakup when the Spanish arrived. Such was the hatred that Cortes had no trouble finding allies, who gave him valuable intelligence and precious help with his transport. Without this he could never have brought his small force up from the coast, guns and all, over the sierra, and into the valley of Mexico. Noche trista, the Spanish called it, and yet it was a miraculous escape. The Mexicans, moreover, could not pursue their advantage and finish them off, in large part because they were tragically weakened by the most subtle and secret of the Spanish weapons, one the invaders did not even know they possessed. These were the Old World pathogens, invisible carriers of death to a population never exposed to these diseases. They had already done terrible work in the Caribbean. Now they laid hundreds of Aztec warriors low at the very moment of their victory. The conquest of the Inca empire was essentially similar: again, a far- flung tributary empire, centralized and ingenious in its administrative structures; but again, internal divisions and hatreds, setting Incas not only against subject tribes but against one another; and again, European disease as a silent partner of European conquest.

Certainly, Columbus was as “rough around the edges” as were most other people around the world at the time. But Columbus did all of us today the benefit of wholly uniting in trade (in both things and ideas) a planet with no edges at all.