Increased Societal Complexity and Diminishing Marginal Returns – Part 4

Why might local officials be acting like ancient Roman Emperors?

In the previous essay we examined how the actions of local government officials resemble those of ancient Roman Emperors before the fall of the Roman Empire in that they are tending to oversee fiscal schemes that hide costs from taxpayers, enact welfare programs that simply throw money at random people, and neglect basic local functions like the provision of sound infrastructure. In this essay, we’ll look at why that might have come to be.

As Joseph Tainter described in his 1988 book The Collapse of Complex Societies, governmental bureaucracy has become so vast that it’s draining the energy from its citizenry. And it’s also draining energy from local government. In fact, the federal government has grown so large that it’s become routine for local governments to look to and rely on the federal government to solve local problems, leading local government to be so focused on federal largess that they neglect local issues themselves.

As Tainter writes, “a governing body that provides goods or services has coercive authority therein. The threat of withholding benefits can be a powerful inducement to compliance.” Offering benefits can also induce acquiescence to that governing body. And the federal government has provided vastly more money to localities in the form of grants-in-aid, as the chart below shows (in billions of dollars per year).

As a result, there’s been a dramatic growth in the number of state, and especially local, government employees, who have increasingly come to administer federal programs by proxy in cooperation with federal government employees.

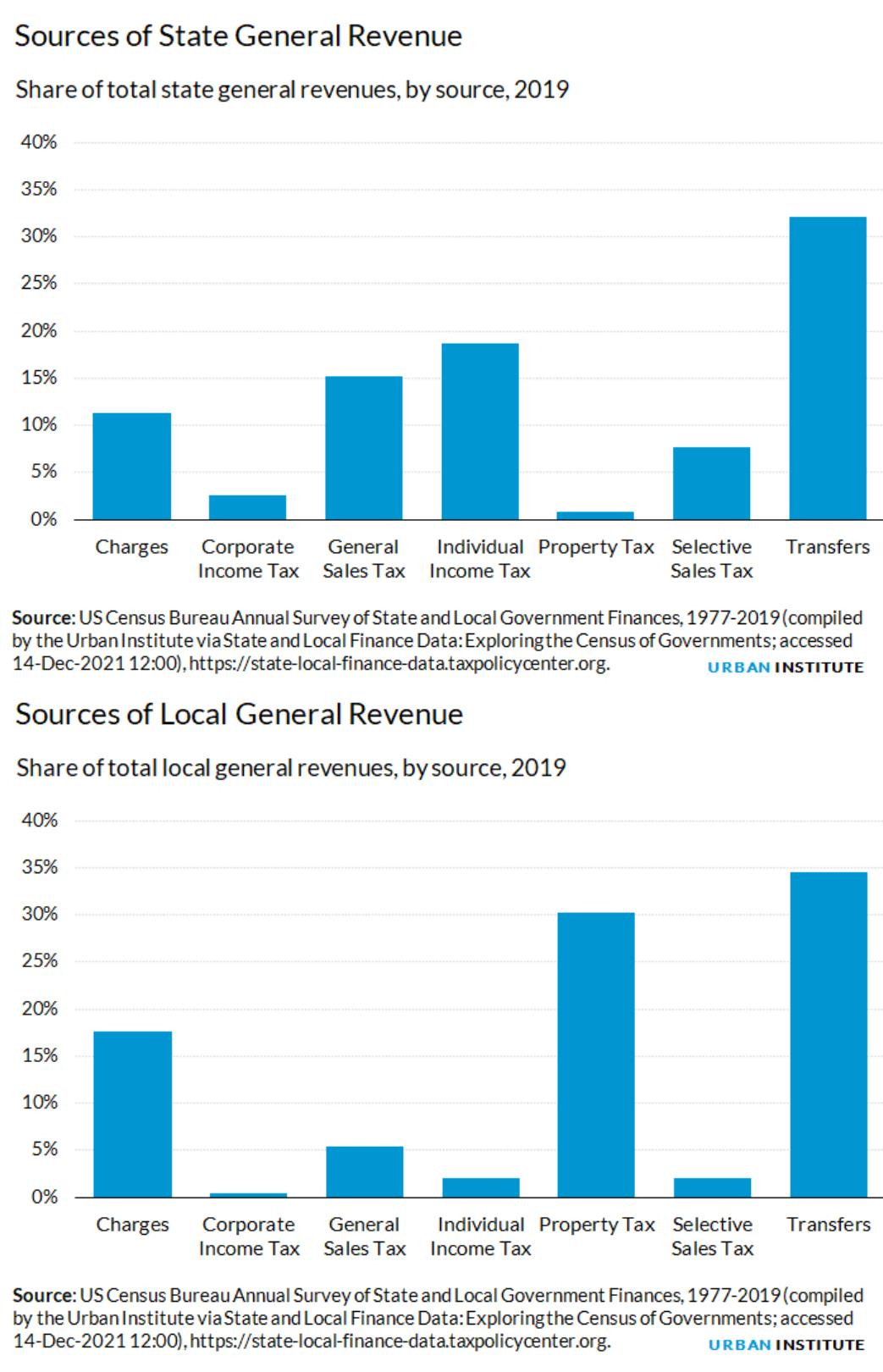

As of 2019 (before the massive COVID-related influx of federal dollars to the state and local level), state government received about 35% of their revenues from the federal government, and local governments in turn received about 35% of their revenues from the state or federal government.

The federal government does have the constitutional authority to condition states’ and localities’ receipt of federal funds on following federal rules. As Joseph Hoffman writes:

Regarding the taxing and spending clause [of the Constitution], Article I, Section 8 states: “The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States …” … The taxing and spending clause provides that federal tax money can be spent for the “general welfare of the United States.” Today, that has become one of the broadest— and most important—sources of federal authority in the entire Constitution … The lead case on the subject is South Dakota v. Dole, which was decided in 1987. The case involved a constitutional challenge to the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984. South Dakota sued Elizabeth Dole, the secretary of transportation. The state argued that the federal statute was a thinly disguised attempt by the federal government to mandate a national drinking age. South Dakota stated that the law exceeded the enumerated powers of the federal government and was incompatible with the broad power of the states to regulate alcohol under the Twenty-First Amendment. In response, the feds argued that although the Twenty First Amendment authorized state regulation of alcohol, it didn’t explicitly prohibit Congress from enacting additional regulations. In Dole, the US Supreme Court decided that there was no need to resolve difficult questions about the scope and meaning of the Twenty-First Amendment. Instead, the court held that Congress had the authority to enact the challenged statute because it was a legitimate exercise of the taxing and spending power. Citing the Butler decision from 1936, the court explained that the taxing and spending power is not limited to the list of federal powers otherwise enumerated in the Constitution. Simultaneously, the court articulated four restrictions on the federal government’s taxing and spending power: The power must be exercised by Congress for the “general welfare”; the federal statute must clearly define the choice presented to the states so that they can decide whether they want to accept the conditions placed on the federal funding; the federal government must act in pursuit of a federal interest in a national project or program; and the federal statute can’t violate any specific prohibitions contained in the Constitution. The court found that all four of these requirements were satisfied by the challenged federal statute in Dole.

The 2022 approved budget for the City of Alexandria consisted of over 11% federal funds and about 8% state funds.

As has been reported:

In April 2020, [the City of Alexandria] projected a budget shortfall of up to $100 million as businesses shut down and workers lost their jobs, eliminating key revenue from sales, tourism and income taxes … But a year later, those dire budget projections still haven’t become a reality … Thanks to generous federal relief funds, a rebound in consumer spending and stock market gains, state and local governments that had predicted economic calamity are now finding themselves flush with cash.

When local municipalities become beholden to federal funding, and the federal strings attached to that funding, they devote fewer resources to addressing unique local problems, with potentially calamitous results. The New England Complex Systems Institute, in its article “An Introduction to Complex Systems Science and Its Applications,” makes the following analogy:

One danger of interdependencies is that they may make systems appear more stable in the short term by reducing the extent of small-scale fluctuations, while actually increasing the probability of catastrophic failure … As a thought experiment, imagine 100 ladders, each with a 1/10 probability of falling. If the ladders are independent from one another, the probability that all of them fall is astronomically low (literally so: there is about a 10 [to the 20th power] times higher chance of randomly selecting a particular atom out of all of the atoms in the known universe). If we tie all the ladders together, we will have made them safer, in the sense that the probability of any individual ladder falling will be much smaller, but we will have also created a nonnegligible chance that all of the ladders might fall down together.

The strings attached to federal funding streams are the ropes tying those ladders together. And as the researchers at the Institute point out, in a

system with a high degree of complexity, the potential positive impact of a change is generally much smaller than its potential negative impact … This phenomenon is a consequence of the fact that, by definition, a high degree of complexity implies that there are many system configurations that will not work for every one configuration that will … A tightly controlled (top-heavy) hierarchy is not well suited to environments in which there is a lot of variation in the systems with which the lower levels of the hierarchy must interact … For example, centralizing too much power within the US governance system at the federal (as opposed to the local or state) level would not allow for sufficient smaller-scale complexity to match the variation among locales.

Today, the federal government is the most top-down of all the top-down entities in America, and now it largely controls even local-level decision-making through its funding streams, creating an exponentially large mismatch between local needs and federal policy. And as Joseph Tainter reminds us in his book The Collapse of Complex Societies, when such mismatches become significant enough, societies can collapse.

Of course, no one expects anything like the particular collapse of the Roman Empire here in America any time soon. The situation today worldwide is significantly different than it was two thousand years ago. As Tainter writes, “The occurrence of declining marginal returns, then, need not always lead to collapse: it will do so only where there is a power vacuum. In other cases, it’s more likely to be a source of political and military weakness, leading to slow disintegration and/or change of regime.” In other words, with so many national powers around the world today, anything approaching collapse by one nation will simply be met by its domination or absorption by one of the other competing powers. As Tainter summarizes:

There are no power vacuums left today. Every nation is linked to, and influenced by, the major powers, and most are strongly linked with one power bloc or the other … Collapse today is neither an option nor an immediate threat. Any nation vulnerable to collapse will have to pursue one of three options: (1) absorption by a neighbor or some larger state; (2) economic support by a dominant power, or by an international financing agency; or (3) payment by the support population of whatever costs are needed to continue complexity, however detrimental the marginal return. A nation today can no longer unilaterally collapse, for if any national government disintegrates its population and territory will be absorbed by some other.

Still, the longer governments continue to deliver only diminishing marginal returns to their citizens, the more likely they’ll come to be absorbed by other governments that have more to offer. That’s not an invasion by barbarians, but still a situation best avoided.

How best to avoid that situation? That’s the subject of the next essay in this series.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5.

I learn something from every essay you write. I don't often find that. Once again, many thanks.