Increased Societal Complexity and Diminishing Marginal Returns – Part 3

Signs of ancient Rome in Alexandria, Virginia.

I live in Alexandria, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, D.C. It’s home to many people who work for the federal government, and for various interest groups that rely on the federal government to implement the programs they lobby for. It’s geographically close to the nation’s capital, and in that sense it may be unique. But as we’ll soon see, every locality in America today, if not geographically close to Washington, D.C., has become similarly financially and regulatorily entwined with the federal government, and in that sense Alexandria is much like every other urban or suburban locality nationwide.

So what are some of the signs of decline shared by ancient Rome then and Alexandria, Virginia, today?

Debasing the Currency

Corrupt Roman officials significantly debased the currency. As Tainter writes in his 1988 book The Collapse of Complex Societies:

When extraordinary expenses arose the supply of coinage was frequently insufficient. To counter this problem, [Emperor] Nero began in 64 A.D. a policy that subsequent emperors found increasingly irresistible. He debased the silver denarius, raising the content of base metal to ten percent. He also reduced somewhat the size of both the denarius and the gold aureus (a coin initially worth 25 denarii) … Serious stress surges, in the form of barbarian incursions, began to affect the Empire in the mid second century A.D., and increasingly thereafter. Unable to bear the cost of meeting these challenges out of yearly productivity, the emperors adopted a strategy of artificially inflating the value of their yearly budgets by debasing the currency. This shifted the cost of current crises to future taxpayers. Such a strategy assumes that the future will experience no equivalent crisis. When this assumption proved grossly in error, the existence of the Empire was imperiled. By debasing the currency, increasing taxes, and imposing stringent regulations on the lives of individuals, the Empire was, for a time, able to survive. It did so, however, by vastly increasing its own costliness, and in so doing decreased the marginal return it could offer its population. These costs drained the Empire’s peasantry so thoroughly that population could not recover from outbreaks of plague, producing lands were abandoned, and the ability of the State to support itself deteriorated. As a result, the barbarian incursions of the late fourth and fifth centuries were increasingly successful and devastating. The advantage of empire declined so precipitously that many peasants were apathetic about the dissolution of Roman rule, while some actively joined the invaders. In being unable to maintain an acceptable return on investment in complexity, the Roman Empire lost both its legitimacy and its survivability.

Local officials can’t debase the currency directly, but they can hide the costs of the city bureaucracy from taxpayers, foisting those costs on them at some indeterminate point in the future. In 2012, for example, the City of Alexandria was relying on current and future taxpayers to pay city employee pension and post-employment healthcare obligations to the tune of $138 million and $84 million (respectively) as of 2007, according to the City’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, which lists them as “Unfunded Actuarial Accrued Liability” (UAAL) (see Exhibit XVI at pages 111-113). These were expenses that should have been recognized and recorded in prior years’ budgets and income statements. As a result, the entire $222 million is having to be paid by taxpayers after the fact and in contravention of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles for “accrual accounting,” which requires a “matching of income and expenses.”

The City hid OPEB [Other Post-Employment Benefits] expenses until June, 2007, after which the Governmental Accounting Standards Board began recommending that it at least be reported. (And note that private sector employers haven’t been allowed to use such accounting practices themselves to account for pension obligations since enactment of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974.)

Local politicians would have us believe these unfunded liabilities are all attributable to the Great Recession of 2008. But as can be seen from these numbers in 2007, the root causes had been there for many years and reflect systemic failures in accounting for changes in annual pension multipliers and COLA (cost-of-living) adjustments, overly optimistic assumptions about investment returns, outdated mortality tables, and chronic underfunding of annual contributions.

Sadly, accounting gimmicks like these have fooled many people for a very long time, and with the direction math education is going at the local level, they may fool many more people into the future, just as they fooled the ancient Romans. Tainter describes how a decline in math education led to accelerated civilizational decline in ancient Rome:

The [Roman] Empire … emerged at the turn of the fourth century A.D. as a very different entity. This is a period for which comparatively little documentation exists, but that in itself may be symptomatic. Literacy and mathematical training apparently declined during the third century. This resulted not only in the unsatisfactory documentation of the period with which historians must deal, but must also have affected the Imperial government. As fewer people could read or count, the quality and quantity of information reaching the government during this critical time would have declined. In Egypt after 250 A.D. census registration came to a halt … The major emphasis of what education remained was rhetoric, and that was not really relevant to the needs of the government. There was at the same time an increase in mysticism, and knowledge by revelation.

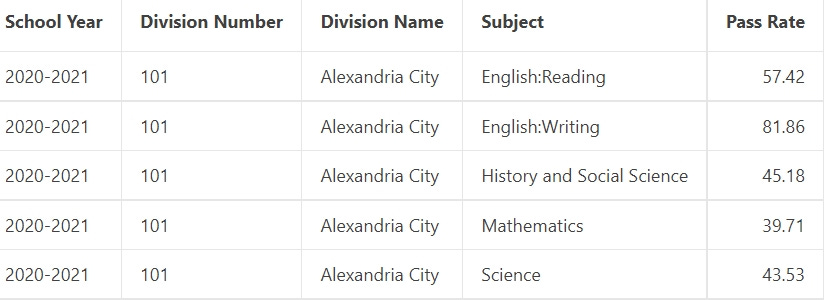

As I described in a previous essay, public school students in the state of Virginia, where I live, recently suffered severe learning losses in math. As researchers have pointed out, of the states they studied, Virginia had one of the highest shares of school district-time spent in fully virtual learning during the COVID pandemic, and the largest losses in math learning, registering a 31.9 percentage point decline in performance on the standardized math test. In the City of Alexandria, the Standards of Learning pass rate on the mathematics test for the 2020-21 school year was only 39.71 percent.

At the same time, even as the City receives more and more money from the state and federal governments, it’s collecting more taxes from its citizens. Every year, slightly more people move to the Washington, D.C. metro area to work for the federal government or entities associated with it somehow, primarily through government contracts or lobbying. As a result, the value of real estate has gone up (consistently beating national trends, even through recessions).

And since localities raise most of their taxes in property taxes, the City of Alexandria and other suburbs of the nation’s capital have continued to collect larger and larger amounts of money from property owners even if real estate tax rates (the percent of real estate value assessments the localities take in taxes every year) haven’t fluctuated much. And so simply by being close to the nation’s capital, its suburbs end up collecting more and more money every year, far exceeding population growth. As was reported in 2021, “The City of Alexandria reduced its real estate tax rate for residences by 2 cents to $1.11 per $100 of assessed value … However, thanks to a significant increase in the assessed value of homes, most residential property owners will be paying more in real estate taxes in the coming year … Alexandria city residents will [also] pay much more in stormwater fees as the City of Alexandria significantly increases funding to deal with increasingly frequent floods. Earlier this spring, city council approved increasing stormwater fees from $140 to $280 per year for single-family homes (less for condos and townhomes), with more increases possible in the future.” And such an increase was enacted by the city council in September, 2022.

The Alexandria City Council unanimously adopted a Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 General Fund Operating Budget of $770.7 million. The City’s population as of 2022 was 161,000, meaning the City alone spends about $4,790 for every man, woman, and child in the city.

Throwing Money at People

There was a large welfare state in the Roman Empire before its demise. As Tainter writes:

At all times the major expense was the military, although the Roman dole was not inconsequential. Julius Caesar found 320,000 beneficiaries, nearly one citizen in three. He reduced this to 150,000, but the figure rose again. From Augustus to Claudius (41-54 A.D.) approximately 200,000 heads of families received free wheat … During some of the darkest times, [Roman Emperor] Aurelian (270-5) felt compelled to increase the expense of the Roman dole, issuing loaves of bread rather than wheat flour, and offering pork, salt, and wine at reduced prices. In the decade before Aurelian, Alexandria and other Egyptian cities had been added to the dole.

The Roman observer Suetonius describes Nero’s program of throwing money to random people at the Coliseum: “[Nero] gave many entertainments of different kinds … Every day all kinds of presents were thrown to the people; these included a thousand birds of every kind each day, various kinds of food, tickets for grain, clothing, gold, silver, precious stones, pearls, paintings, slaves, beasts of burden, and even trained wild animals; finally, ships, blocks of houses, and farms.”

Recently, the City of Alexandria initiated a “Guaranteed Income Program” that will:

provide monthly recurring cash payments of $500 to 150 randomly selected residents for 24 months. The cash payment is unconditional, with no work requirement and no restrictions on how it is to be spent.

That local cash giveaway program is being funded entirely by federal taxpayers. As the City of Alexandria states, “On July 6, 2021, the Alexandria City Council approved the use of $3 million of the City’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) allocation for the Department of Community and Human Services to design and pilot a Guaranteed Income Program … Through the passage of ARPA, the City has received a $59.6 million allocation that will be disbursed in two equal tranches through December 30, 2024.” The City even touts the program as having “No work or citizenship requirements.”

Just six months into the program, city officials are spinning it as relieving people’s mental health, while allowing single parents to work less. As reported by a local paper:

A single father with three children in the program was able to quit his second job, Mullen [Economic Mobility Program Officer Julie Mullen] said, and spent more time at home with his children without being as worried about making ends’ meet. “The general sense is that the mental load is lighter,” Mullen said. “Especially for single parents, we know that group, especially in Alexandria, is under a lot of strain.” … “The cost of living is astronomical,” Mullen said. “These are not problems easily solved by getting a better job… we’re really dealing with a bigger systemic problem.”

But an interim report on this program was issued after a year of the program, with poor results. In a vaguely-worded report, the evaluators could only manage to say ARISE participants “may have” improved their financial stability, and “may have” enabled participants to work fewer hours and focus on other responsibilities. The report goes on to say:

Eligible recipients were to receive $500 cash in GI [guaranteed income] payments monthly for two years, followed by five additional months of payments. ARISE began as a 24-month (2-year) pilot and DCHS obtained funding to extend it 5 months, through June 2025 ... This interim brief reports how GI participants are faring during the first year of the pilot period compared with a similar group of Alexandria residents who were not offered and did not receive the monthly cash payment … In addition, the study’s small analytic sample (N=394) means that, for statistical reasons, the GI would need to have very large impacts through 12 months for us to be able to detect them … This brief offers suggestive quantitative evidence, combined with rich interview data. However, we interviewed only a subset of active ARISE participants and no members of the control group.

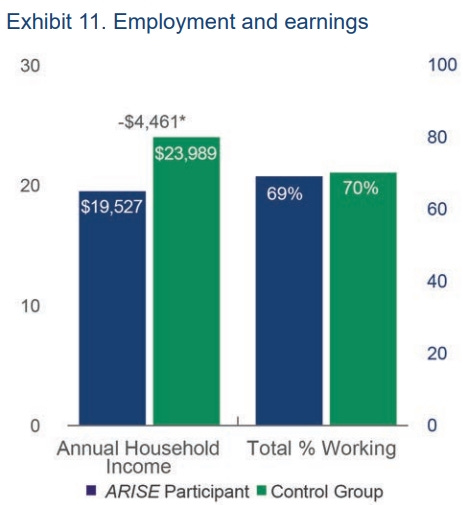

The results showed participants who received the guaranteed income experienced very small improvements in “peaceful and stable home environments compared to the control group,” while they ended up working less:

[Participants] are doing better on some financial measures than the control group even though some participants reduced their paid work hours to pursue other commitments … [T]here was a statistically significant difference in annual household income of nearly -$4,500 for ARISE participants compared with the control group.

So, according to these results, $6,000 in extra taxpayer-paid guaranteed income over the course of a year led to $4,481 less in work-related income from work.

The report notes these losses of work-related income even though efforts were made to reduce the negative results of the so-called “benefits cliff”:

DCHS [Department of Community and Human Services] obtained waivers to protect benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Women, Infants, and Children, Medicaid, Child Care Subsidy Program, and means-tested city programs.

While intended to give people a leg up, other studies have shown such programs just tend to cut the legs out from under potential future workers. Researchers who investigated the long-term effect of cash assistance for beneficiaries and their children by following up, after four decades, with participants in the Seattle-Denver Income Maintenance Experiment (families in this randomized experiment received thousands of dollars per year in extra government benefits for three or five years in the 1970’s) found evidence of significant negative effects on adults decades after the experiment ended. On average, participation in the program decreased the probability that participants worked in a given year by 3.3 percentage points, and decreased average annual earnings by $1,800. Participants in the program were also 6.3 percentage points (20% of the mean) more likely to apply for disability benefits. These effects for adults are large relative to the cash assistance received: for every $1 in additional income received, discounted lifetime earnings were $4.50 lower.

A July, 2022 study by Harvard researchers involved a randomized trial conducted from July 2020 to May 2021, in which the researchers assigned 2,073 low-income participants to receive a one-time unconditional cash transfer of either $500 or $2,000. 3,170 people with similar financial, demographic and socioeconomic characteristics served as a control group. As reported in the Wall Street Journal:

Participants earned an average of about $950 a month and had $530 in unearned income (e.g., food stamps). About 80% had children, and 55% were unemployed. Over 15 weeks they were surveyed about their physical, mental and financial well-being. Forty-three percent also agreed to allow researchers to observe their bank balances and financial transactions … The top-line result: Handouts increased spending for a few weeks—on average $26 a day in the $500 group and $82 a day in the $2,000 group—but had no observable positive effect on any individual outcome. Bank overdraft fees, late-payment fees and cash advances were as common among cash recipients as in the control group. Handout recipients fared worse on most survey outcomes. They reported less earned income and liquidity … These findings contradicted the predictions of 477 social scientists and policy makers the researchers surveyed.

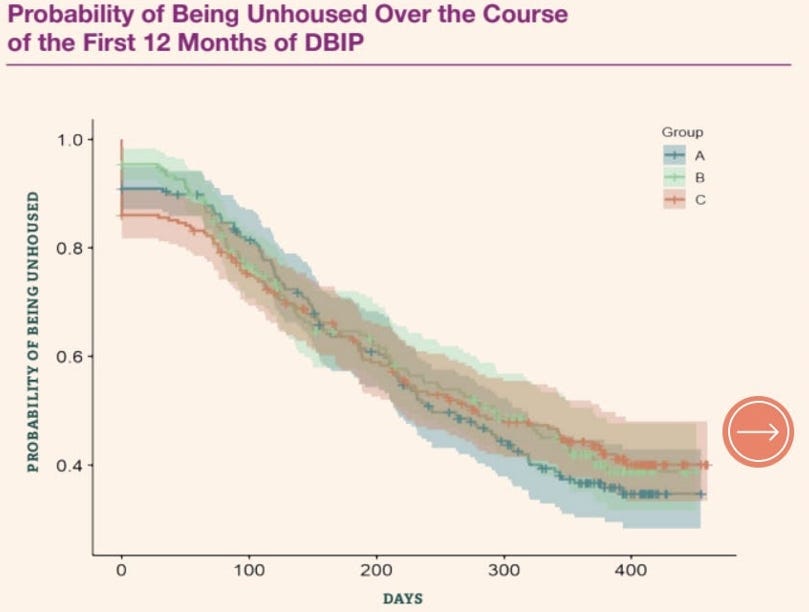

A multi-million dollar study of the recent Denver experiment with UBI showed it had no significant benefits compared to the status quo. As reported in the Free Press:

Denver launched a large and important study, spending $9 million to test out Universal Basic Income with 800 unhoused people. Now we have the outcomes. One group of people got $1,000 a month. A second group got an initial payment of $6,500 then 11 monthly payments of $500, for a total of $12,000 over 12 months. And a third group, the control, was given just $50 a month and social services. Turns out, UBI is no better than normal government services.

The researchers who put this study together were so obsessed with it showing the success of UBI that they announced the results like this: “All payment groups showed significant improvements in housing outcomes, including a remarkable increase in home rent and ownership, and decrease in nights spent unsheltered.” But friends, if your control group (i.e., the fifty bucks a month group) has the same outcome as the Universal Basic Income group (the $1,000 a month folks), that means your UBI intervention didn’t work. Anyway, it’s worth reading the report.

(In sum, the project gave $1000 a month to help reduce homelessness, and the apparent effect on homelessness, relative to the control group, was slim to none.)

And following the most extensive randomized control trial to date to examine the effects of a guaranteed minimum income, the researchers concluded as follows:

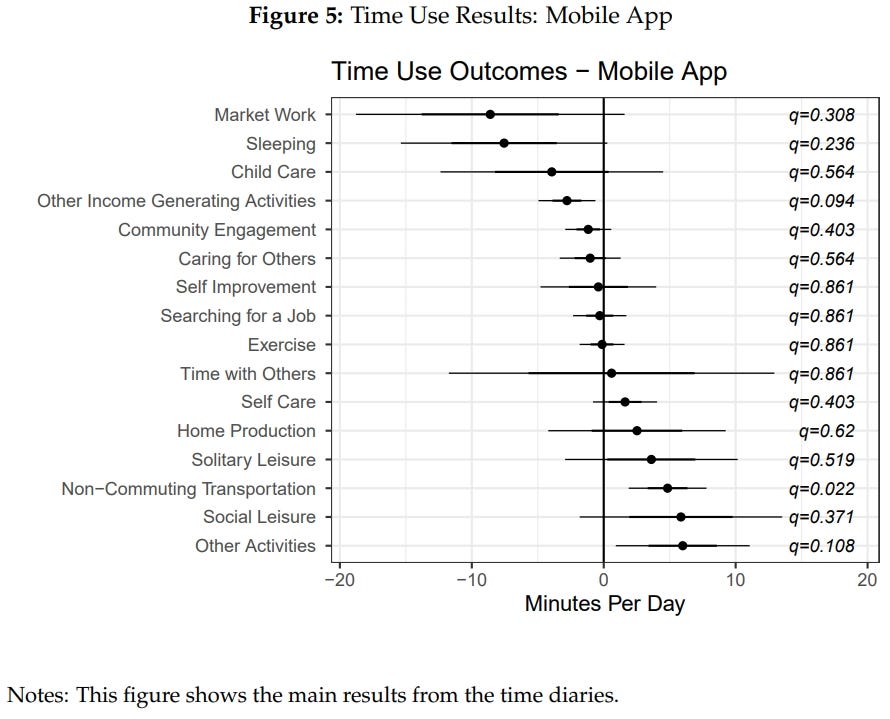

We study the causal impacts of income on a rich array of employment outcomes, leveraging an experiment in which 1,000 low-income individuals were randomized into receiving $1,000 per month unconditionally for three years, with a control group of 2,000 participants receiving $50/ month. We gather detailed survey data, administrative records, and data from a custom mobile phone app. The transfer caused total individual income to fall by about $1,500/year relative to the control group, excluding the transfers. The program resulted in a 2.0 percentage point decrease in labor market participation for participants and a 1.3-1.4 hour per week reduction in labor hours, with participants’ partners reducing their hours worked by a comparable amount. The transfer generated the largest increases in time spent on leisure, as well as smaller increases in time spent in other activities such as transportation and finances … We observe no significant effects on investments in human capital, though younger participants may pursue more formal education. Overall, our results suggest a moderate labor supply effect that does not appear offset by other productive activities … we do find that the transfer we study generated significant reductions in individual and household market earnings. The reductions in individual labor supply we observe are smaller than what has been documented in some settings (e.g., Golosov et al., 2023), but larger than what has been observed in others (e.g., Imbens, Ru[1]bin and Sacerdote, 2001; Cesarini et al., 2017). The spillovers onto other household members–who also reduced their labor supply in response to the transfer–implies the total amount of work withdrawn from the market is fairly substantial. Further, we do not find evidence of the type of job quality or human capital improvements that advocates have hoped might accompany the provision of greater resources, and our confidence intervals allow us to rule out even very small effects of the transfer on these outcomes … [P]articipants in our study reduced their labor supply because they placed a high value, at the margin, on additional leisure.

Recipients of the free extra income reported reducing their time spent on market work and other income generating activities, and increasing their time spent on leisure.

And more than a dozen researchers published the results of a large study in May, 2025 and found:

To study the causal role of income on children’s development, the Baby’s First Years randomized control trial provided families with monthly unconditional cash transfers. One thousand racially and ethnically diverse mothers with incomes below the U.S. federal poverty line were recruited from postpartum wards in 2018-19, and randomized to receive either $333/month or$20/month for the first several years of their children’s lives. After the first four years of the intervention (n=891), we find no statistically significant impacts of the cash transfers on four preregistered primary outcomes (language, executive function, social-emotional problems, and high-frequency brain activity) nor on three secondary outcomes (visual processing/spatial perception, pre-literacy, maternal reports of developmental diagnoses).

A good video by Kite and Key discussing this study’s findings can be found here.

Other researchers have concluded as follows:

The Baby’s First Years study recruited 1,000 low-income mothers of newborns. Shortly after giving birth, mothers were randomized to receive a monthly unconditional cash transfer of either $333 or $20 per month. Follow-up data were collected from mothers approximately 12, 24, and 36 months after the birth of their child. Results: Although the intervention produced a moderate increase in household income and reduced poverty, we observe no detectable improvements in mothers’ subjective reports of economic hardship or the quality of play with their infants, and some small, although mostly non-significant, increases in parental psychological distress and declines in the quality of mothers’ relationships … Conclusion: We find little support for the hypothesis that material hardship, maternal well-being, or family relationships are positively affected by a moderate unconditional cash transfer among families with young children.

And yet another study from November, 2024, researchers gave $500 a month to a group of California households and compared them to a control group who received no money. The households that received the money ended up only $100 richer and actually purchased more cigarettes. They found that UBI had no positive effect on psychological or financial well-being, and didn’t even improve food security. The researchers concluded:

The transfer caused total individual income excluding the transfers to fall by about $2,000/year relative to the control group and a 3.9 percentage point decrease in labor market participation. Participants reduced their work hours as a result of the transfers by 1-2 hours/week and participants’ partners reduced their work hours by a comparable amount. Among other categories of time use, the greatest increase generated by the transfer was in time spent on leisure. Despite asking detailed questions about amenities, we find no impact on quality of employment, and our confidence intervals can rule out even small improvements. We observe no significant effects on investments in human capital …

And in July, 2025, the New York Times reported on yet another study showing no benefits for children resulting from cash assistance:

[A] rigorous experiment, in a more direct test, found that years of monthly payments did nothing to boost children’s well-being, a result that defied researchers’ predictions and could weaken the case for income guarantees. After four years of payments, children whose parents received $333 a month from the experiment fared no better than similar children without that help, the study found. They were no more likely to develop language skills, avoid behavioral problems or developmental delays, demonstrate executive function or exhibit brain activity associated with cognitive development.

And “Alexandria’s Recurring Income for Success and Equity” program is being pushed even as state and federal welfare programs are already being applied to people whose condition of being “in poverty” isn’t what it used to be (and when previous proposals for providing those of low income with cash payments were conditioned on eliminating the rest of the welfare system):

Government welfare checks are said to go to people “in poverty,” but to provide more context to this situation it’s worth assessing what it actually means for someone to be living “in poverty” under official government definitions of the term. To that end, it’s useful to keep in mind that even 15 years ago a large majority of those “in poverty,” according to the Census Bureau, had cable or satellite television, a DVD player, and a video game system, along with cars, microwave ovens, air conditioning, and cell phones. Advancing technology has generally allowed the same types of consumer goods (such as microwaves, air conditioning, personal digital devices, computers, and cell phones) to be readily available to the rich and poor alike. Over the last ten years, Americans generally have come to spend 8 percent more time watching television, and 5 percent less time working.

As the Wall Street Journal writes regarding yet another study of the issue:

Researchers with the nonprofit OpenResearch and several universities ran a randomized controlled trial to test the impact of a cash transfer on lower-income, working-age Americans. One group received $1,000 every month for three years—$36,000 total—no strings attached. The other were paid $50 a month to participate as a control group. OpenResearch says the study showed that “parents improved their parenting practices and made meaningful investments in their children and themselves.” But drill down, and the findings are uninspiring. Those who received the $1,000 payments did report better parenting behavior in surveys, though they may have been more inclined to say this because they were receiving free money. They also spent more money on their children. On the other hand, they reported that their children experienced more developmental difficulties and stress than the control group. The authors suggest that parents receiving cash might simply have been more attentive to their children’ problems than those in the control group. Notably, while the transfer payments reduced parents’ self-reported stress levels during the first year of the study, the “effects were short-lived and dissipated by the second year,” the researchers write. The handouts also “did not have a meaningful effect on most educational outcomes measured in school administrative records,” including attendance, disciplinary actions or repeating a grade. Illinois children whose parents received free cash had worse grades, though this negative effect was not statistically significant after researchers adjusted for other variables. The payments also did not “affect characteristics of the home environment, child food security, exposure to homelessness, or parental satisfaction.” … The researchers reported last year that the cash transfers increased healthcare utilization, including hospital and emergency care, but this produced no measurable effects on physical health outcomes. A study of Oregon’s Medicaid expansion in 2008 came to a similar conclusion. Recipients also worked less, equivalent to roughly eight fewer days in the previous year. Yet OpenResearch touts that “average household income was roughly $6,100 higher for recipients than control participants, including the transfer amount” and payments “increased agency to work fewer hours or reduce the number of jobs held.” In other words, the payments led people to work less. The results mesh with other evidence that a guaranteed annual income isn’t the path to upward mobility. It might even make that mobility less likely. Increasing the incentives to work and become less dependent on government is a better way to help the poor rise.

Crumbling Infrastructure

Dilapidated infrastructure was one of the hallmark signs of a downswing in the Roman Empire. As Maher writes of the drainage improvements made under Emperor Claudius (who reigned from 41-54 A.D.):

Some distance outside Rome lay Fucine Lake, a large body of water with no adequate outlet; it had become a stagnant breeding place for malaria, and it frequently flooded neighboring land. A tunnel 5.6 kilometers long was built to drain this lake …” But then under Emperor Nero (who reigned from 54-68 A.D.) the funding of drainage infrastructure plummeted: “Throughout his reign, Nero lavished money on people and squandered the resources he controlled … [A]s time went on, he spent increasingly little on infrastructure.

So, too, in Alexandria today. In the City of Alexandria, the problem of flooding is caused by a long history of failure to install enough functioning underground stormwater containers to slow water flows across surfaces. As one article reports:

Between roads and small residential lots with little green space, urban areas have large amounts of impermeable surfaces, or surfaces that can’t absorb water. And because historically, urban areas weren’t designed for stormwater management, the older and denser the city, the more impermeable surface it tends to have. Alexandria is a good example. According to [Jess] Maines [chief of Alexandria’s stormwater management division], about 48 percent of the city’s land area is impervious surface; in its oldest part, historic Old Town, about 85 percent is.

The neglect of drainage in the city has been a long-running problem that required the Virginia state legislature to enact a law requiring Alexandria to fix or replace its antiquated sewer system by July 1, 2025. As the Washington Post reported in 2018:

The 200-year-old combined sewers in Old Town for decades have overflowed into the river whenever it rains, because the underground system can’t handle normal effluent from tubs, toilets and sinks as well as rainwater runoff. The overflow violates the federal Clean Water Act. Alexandria began to address the issue several years ago, knowing that a state deadline was approaching for fixing three of the four outfalls. But the city’s initial plan left the largest outflow untouched, until residents, environmentalists and downstream state legislators raised an outcry. The General Assembly then passed a bill that required the city to fix the sewers by 2025, despite local objections that the deadline was unrealistic.

The City of Alexandria has had to draw on both state funding for the sewage project and federal funds to begin solving its local drainage problems.

On July 8, 2022, the City of Alexandria issued a press release announcing a Virginia budget bill was enacted that included $40 million for the City’s Combined Sewer Overflow project and $50 million in American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding previously appropriated to the project.

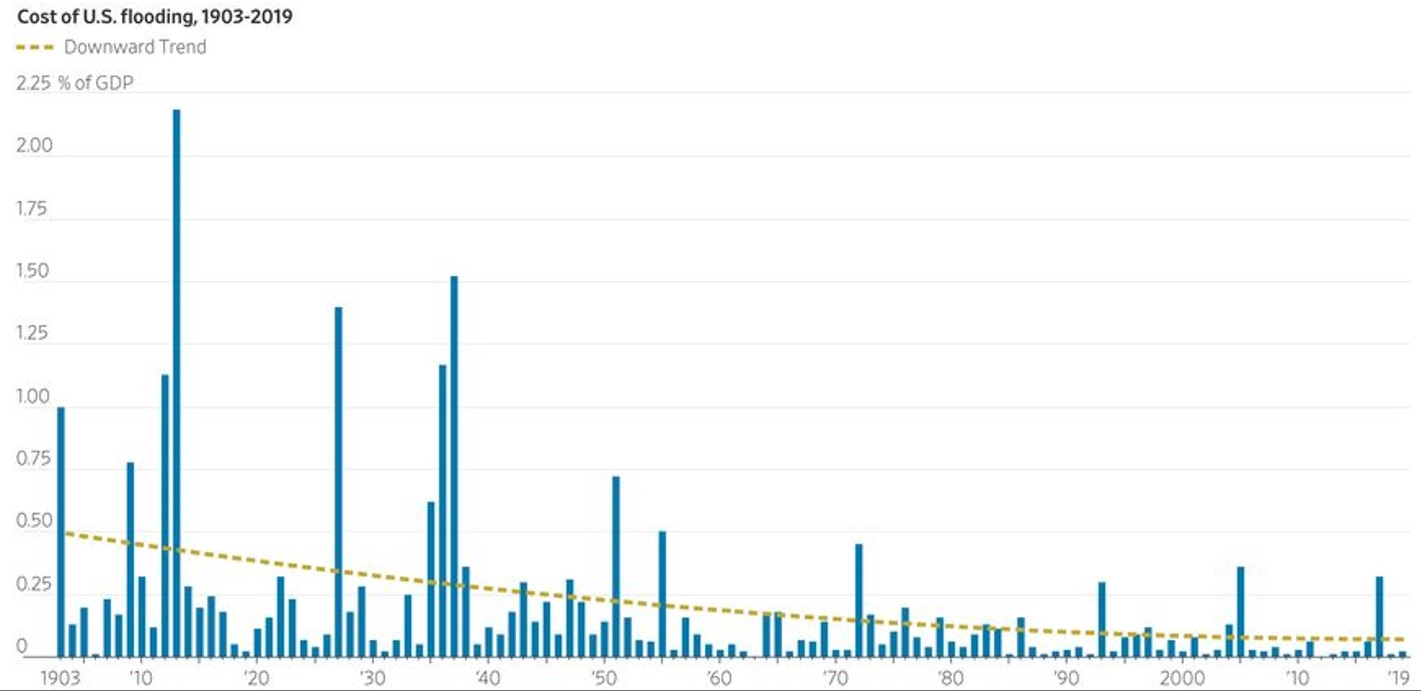

Despite this history of local infrastructure neglect followed by state bailouts, defenders of the status quo in local government blame “climate change” for increased flooding (see the previous essay series on climate change here). In September, 2022, the Alexandria City Council even set aside “$1.85 million in FY 2023 Contingent Reserve funding … for climate change initiatives for the creation of an ‘Office of Climate Action’ within the City Manager's Office.” But as Bjorn Lomborg writes in the Wall Street Journal, thanks to mitigation measures employed in the rest of the country, “the relative toll that floods take on the U.S.—in property and lives—has decreased over time. Flooding costs as a share of gross domestic product declined almost 10-fold since 1903 to 0.05% of GDP.”

The City Manager Model of Local Government

Another interesting aspect of some municipal governments is that many of them, such as the one in Alexandria, Virginia, are generally run by an unelected official called the City Manager, who puts together the base city budget the city council votes to approve. City Managers are hired in cities governed by what’s called a “weak mayor” system, in which the mayor and city council have much less practical responsibility over the city budget and other local affairs.

Here are the approximate salaries of these officials in Alexandria, Virginia:

City Manager Salary: $288,000

Mayor salary: $41,600

City Council Member Salary: $37,500

The mayor and city council members can propose additions to, and deletions from, the budget submitted by the City Manager, but in the City of Alexandria, those fiscal contributions of the mayor and city council are quite small. For example, for 2022, the total city budget was $770,700,000. The mayor and city council contributed $3,028,685 to the budget that year through amendments ($2,329,909 of which came from their voting to eliminate library late fees ($70,000), eliminate local bus fares ($1,470,000), and to eliminate police officers in public school buildings and replace them with “mental health” professionals ($789,000) who will presumably err on the side of declaring more teens as having mental disorders to justify their services).

So the total contributions of the elected city officials to the city budget (through public votes) is only about 0.4%, with the City Manager contributing 99.6% of the city budget. Based on their contributions to the city budget, then, the mayor and city council might warrant salaries of about $1,152, but they get about 33 times that much. (This year, for the 2023 budget, the mayor and city council contributed through their amendments to the City Manager’s budget an additional $8.5 million in increased taxes and spending, which also amounts to only about 0.5% of the City Manager’s original proposed budget of around $1.5 billion.) And in an update for 2024: as a local newspaper reports, “The Alexandria City Council voted unanimously to increase the salaries for the next Council during a public hearing on June 15 [2024]. Both Alexandria’s next mayor as well as the six members of City Council will each receive raises of $30,500,” which amounts to an 81% pay raise.

Anyway, back to our story. So why might small town mayors (like our Mayor, Justin Wilson) be acting like Emperor Nero? That will be the subject of the next and last essay in this series.

[Author's note: Many thanks to reader Doby Fleeman for his contributions to the municipal finance portions of this essay.]

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5.

Paul, Fascinating. I am increasingly enjoying your perspective on almost any subject you choose. Thanks for improving my day/life.

The USA is suffering from decadence and it’s not clear what the cure is. No leadership or discipline.