Increased Societal Complexity and Diminishing Marginal Returns – Part 2

The basics on analyzing today’s complex systems.

In the last essay we looked at an analysis of why civilizations throughout history have collapsed. That analysis, in Joseph Tainter’s 1988 book The Collapse of Complex Societies, concluded civilizational collapse was due to the inevitable growth of a bureaucratic over-complexity that came to produce only increasingly diminishing marginal returns for a citizenry that had been sapped of its resources in order to support that ever-growing bureaucratic complexity. In this essay we’ll look at more of the work of the New England Complex Systems Institute, and how it seeks to tease out the essential causes of various problems from today’s vast complex of potential causes.

The Institute published a useful summary of its approach to examining complex systems in a paper titled “An Introduction to Complex Systems Science and Its Applications.” Recognizing that mathematical analysis can unify our understanding of patterns wherever they appear, in both nature and human organization, they set out their approach, as follows:

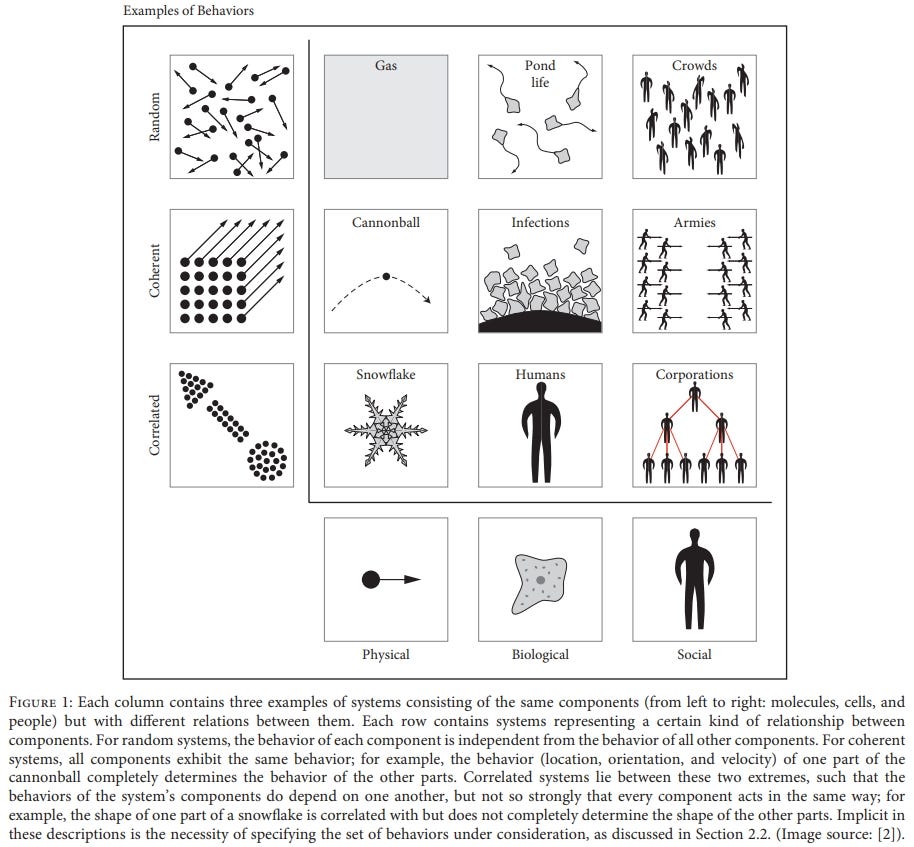

[F]rameworks exist for understanding particular components or aspects of systems, the standard assumptions that underlie most quantitative studies often do not hold for systems as a whole, resulting in a mischaracterization of the causes and consequences of large-scale behavior … [W]hile most scientific disciplines tend to focus on the components themselves, complex systems science focuses on how the components within a system are related to one another. For instance, while most academic disciplines would group the systems in Figure 1 by column, complex systems science groups them by row.

In the book Making Things Work: Solving Complex Problems in a Complex World, Yaneer Bar-yan of the Institute points out that “Indeed, one of the main difficulties in answering questions or solving problems – any kind of problem – is that we think the problem is in the parts, when it really in the relationships between them.” In essence, that is the sort of problem amenable to solutions found through calculus (discussed in a previous essay), which analyzes how, when one or more factors change, other factors change as a result, and how even more factors might change as a result of those interactions.

Like Joseph Tainter, the Institute describes how complex systems face the problem in which, as a system becomes larger, it becomes less adaptable to new circumstances:

The intuition that complex systems require order is not unfounded: for there to be complexity at larger scales, there must be behaviors involving the coordination of many smaller-scale components. This coordination suppresses complexity at smaller scales because the behaviors of the smaller-scale components are now limited by the interdependencies between them … Thus, for any system, there is a fundamental tradeoff between the number of behaviors a system can have and the scale of those behaviors … The fundamental tradeoff is evident in the fact that if [a] factory wants to be able to churn out many copies of a single type of good in a short amount of time, it will have to coordinate all of its workers (perhaps having them work on an assembly line), thereby reducing their individual freedom to make many different kinds of goods. The factory’s production would then have low complexity but at a large scale (e.g., churning out many identical Model-T Fords—“Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black”). On the other hand, if the factory’s employees work independently, they will be able to create many different types of products, but none at scale … Thus, a very efficient system will, due to its necessarily lower complexity, not be as adaptable to unforeseen variations within itself or its environment, while a very adaptable system, designed to handle all sorts of shocks, will necessarily have to sacrifice some larger-scale behaviors. The Soviets thought they could have their cake and eat it, too: they originally believed that their economy would outperform capitalist ones because capitalist economies have so much waste related to multiple businesses competing to do the same thing. It would be far more efficient to coordinate all economic production. But in creating such large-scale economic structures, lower-scale complexity was sacrificed, resulting in a nonadaptive system.

They ask, “When, then, is complexity at a particular scale desirable?” And they answer that

to be effective, a system must match (or exceed) the complexity of the environmental behaviors to which it must differentially react at all scales for which these behaviors occur … Problems arise not from too much or too little complexity (at any scale) per se but rather from mismatches between the complexities of a task to be performed and the complexities of the system performing that task … The failure of command economies provides a stark example: the allocation of resources and labor is too complex a problem for any one person or group of people to understand. Markets allocate resources via a more networked system: decisions regarding how to allocate resources are made without any individual making them, just as decisions are made in the human brain without any neuron making them.

As they continue:

The question thus becomes: how do we design systems that exceed the complexity of the decisionmakers within them? … While uncertainty makes most systems weaker, some systems benefit from uncertainty and variability … [O]ur psychologies are strengthened by exposure to adversity, provided the adversity is not too severe … Competitive market economies provide another example of how systems can thrive on uncertainty. Due to our ignorance of which will succeed, many potential innovations and businesses must be created and improved upon in parallel, the successful ones expanding and the unsuccessful ones failing. The successful among these can then be improved upon in the same manner—with many approaches being applied at once—and so on … In order to thrive in uncertainty and exceed the complexity of individual decision-making, systems can incorporate evolutionary processes so that they, even if very limited at first, will naturally improve over time. The first step is to allow for enough variation in the system, so that the system can explore the space of possibilities. Since a large amount of variation means a lot of complexity and complexity trades off with scale, such variation must occur at smaller scales (in both space and time). For example, in the case of governance, enabling each city to experiment independently allows for many plans to be tried out in parallel and to be iterated upon … However, even when armed with all the proper information and tools, human understanding of most complex systems will inevitably fall short, with unpredictability being the best prediction. To confront this reality, we must design systems that are robust to the ignorance of their designers and that, like evolution, are strengthened rather than weakened by unpredictability.

The more ideal governing situation the researchers at the Institute describe — a situation in which power is distributed more horizontally rather than vertically — would do much to alleviate the problem Joseph Tainter flagged for collapsing civilizations, discussed in the previous essay: namely, when power is distributed vertically in a complex society, the increasingly complex bureaucracy created leads to the need to take more and more resources from the citizenry, but yields increasingly diminishing (and even negative) marginal returns for those citizens. But when power is distributed more horizontally, more efficiencies will arise and fewer resources will have to be spent on ever-larger bureaucracies that have to supervise ever-larger jurisdictions.

The Roman Empire was a particularly top-down operation, and its trajectory is instructive for other countries operating under a vertical distribution of power. As Joseph Tainter writes in The Collapse of Complex Societies, “The Roman Empire is the prime example of collapse; it is the one case above all others that inspires fascination to this day. A vast empire with supreme military power and seemingly unlimited resources, its vulnerability has always carried the message that civilizations are fleeting things.”

It’s easy to dismiss claims that anything today can significantly parallel what happened in ancient Rome -- a far-away place that existed a couple thousand years ago -- amidst the exponential increase in knowledge that has occurred since then. But as Tainter points out, the very existence of advanced, complex societies is a relatively recent phenomenon, and ancient Rome and America today are framed in the same recent segment of human history:

The citizens of modern complex societies usually do not realize that we are an anomaly of history. Throughout the several million years that recognizable humans are known to have lived, the common political unit was the small, autonomous community, acting independently, and largely self-sufficient. Robert Carneiro has estimated that 99.8 percent of human history has been dominated by these autonomous local communities. It has only been within the last 6000 years that something unusual has emerged: the hierarchical, organized, interdependent states that are the major reference for our contemporary political experience.

And as George Maher describes in his book Pugnare: Economic Success and Failure, we have no reason to think human nature itself has changed all that much in the last 2,000 years:

I learned about this world [the Roman Empire] at school. I had learned about a world of armies, of emperors, and of invading barbarians who had come in and destroyed this world. That history had been a succession of dates of battles I never could keep in my head, which I memorized the night before the exam and forgot the day after. Those dates were difficult numbers for me to remember because I could see no pattern to them. Why should this have happened then and not earlier or not at all? There was, however, a pattern to these numbers which would emerge over time … [T]he people the barbarians encountered were not rich and powerful; they were not the politicians, noblemen, shopkeepers and traders who had lived prosperous and peaceful lives here. Long before these barbarian men had entered this city, it had destroyed itself, and most of those prosperous people had left and the markets were quiet … There was poverty in this city for two hundred years before the barbarians came. A city [Rome] that once had overwhelmed the world with its power and wealth had been reduced, depopulated, and weakened. This it had done to itself … Aside from the science, the world of Rome was in many ways as good as ours, and the people who lived then were much the same as the people who live now. People have not changed in the last two thousand years or indeed in the last hundred thousand years. There were the same angry and contented people, those with ambition, those content to keep things as they are, those with hope and those without … We can look at where things went well for them, and badly, and learn from that. Perhaps some of the things we dread are not so bad after all. And, perhaps, some of the things we think of as harmless are what should bother us most.

Also, as Robin Hanson writes:

To those who see just how much better is a civilized life, one of the most terrifying things one can learn from history is that pretty much all past civilizations fell [and] internal decay contributed a lot to most of those falls. And often internal decay was the main direct cause. Often population declined, often due cultural decay.

Indeed, James Madison, our most prominent constitutional Founding Father, was a keen student of human nature who incorporated principles of human psychology into his understanding of what the Constitution should require. As Madison wrote in Federalist Paper Number 51, drawing on his study of history:

[W]hat is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

Recognizing that while technology may separate us from past civilizations, human nature doesn’t, many people have written about the similarities between ancient Rome prior to its collapse and the modern America federal government -- including strains on private resources, ever-increasing government debt, and ever-expanding government commitments to welfare and entitlement programs that reduce incentives for productive work.

But the problem of diminishing marginal returns that follows from ever-increasing bureaucratization is so pervasive in America today that it has seeped well down to the local level, where one might expect it to be more easily perceived. However -- perhaps in part because people are increasingly looking down at their smart phones and perusing the latest “hot takes” on national news -- few people are aware of the sort of ancient Rome-style decline that infects the local government all around them.

In the next essay, we’ll look at the surprising parallels between the causes of the fall of ancient Rome due to diminishing marginal returns, and the kinds of diminishing marginal returns we see today, even down at the local municipal level.

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5.

I've sent these essays to our local very small town selectman - a Republican who no matter is still eager to give the people "what they want" - daycare, battered women's shelter, senior center, visitor center, etc. etc....the bureaucracy grows, it never ends. And in our small town life gets very complicated. No one seems to operate with an idea or theory of how to govern. There's really no leadership to speak of but rather managers. It's always taking the path of least resistance so you can remain in office. Bread & Circuses. It's very disheartening. No one really cares and in the end we all die....

Paul, I have been reading your Substack for some time now. Your work is different, academically sound, insightful and well written. I see that sometimes I am the only "like". I cannot figure that out, but wanted you to know that at least this voracious reader appreciates what you are doing. I hope your readership continues to grow. The product deserves it.