Increased Societal Complexity and Diminishing Marginal Returns – Part 5

The path to reform through the middle ground of states.

In previous essays we looked at the problems caused by societies based on top-down power structures such as our, which is increasingly dominated by the federal government, down to the local level.

What might be the path to reform? Whatever path there is, it’s not very clear. Whereas science can discover new and more efficient sources of energy, there isn’t much science can do to further improve the efficiency of human organizational enterprises, which will always contain within them the elements of human fallibility and incentives toward bureaucracy, especially in the government sector. As Tainter writes in his 1988 book The Collapse of Complex Societies:

Economists base their beliefs on the principle of infinite substitutability. The basis of this principle is that by allocating resources to R&D, alternatives can be found to energy and raw materials in short supply. So as wood, for example, has grown expensive, it has been replaced in many uses by masonry, plastics, and other materials. One problem with the principle of infinite substitutability is that it does not apply, in any simple fashion, to investments in organizational complexity. Sociopolitical organization, as we know, is a major arena of declining marginal returns, and one for which no substitute product can be developed. Economies of scale and advances in information-processing technology do help lower organizational costs, but ultimately these too are subject to diminishing returns.

As Tainter points out, trends toward collapse can be reversed by simply retreating to methods that increase, rather than decrease, marginal returns:

To the extent that collapse is due to declining marginal returns on investment in complexity, it is an economizing process. It occurs when it becomes necessary to restore the marginal return on organizational investment to a more favorable level. To a population that is receiving little return on the cost of supporting complexity, the loss of that complexity brings economic, and perhaps administrative, gains.

But when even local governments have become part of the federal bureaucracy’s relentless march toward diminishing marginal returns, reversing that march will prove exceedingly difficult.

Yet maybe people can begin to march halfway back from the brink of the federal government, and come to rest at least half the distance toward local government, to the state level, which is where James Madison hoped the center of government gravity would be all along. The United States is the longest-surviving constitutional republic in part because its constitution’s primary author, James Madison, closely studied the causes of the collapse of previous grand civilizations. The Federalist Papers, co-authored by Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, and written as an authoritative defense of the proposed Constitution, are replete with references to the lessons of history as told through the rise and fall of ancient Rome and other once-dominant empires. And one of the lessons Madison took from that history was that partisan factions could most easily come to dominate smaller geographic regions (such as localities), making the ideal center of any political arrangement the geographically larger states that would have the most power under the Constitution, just below a federal government with strictly limited powers. As Madison wrote in Federalist Paper Number 10:

By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community. There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction: the one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects … By what means is this object attainable? Evidently by one of two only. Either the existence of the same passion or interest in a majority at the same time must be prevented, or the majority, having such coexistent passion or interest, must be rendered, by their number and local situation, unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression … [T]he greater number of citizens and extent of territory which may be brought within the compass of republican than of democratic government [is] principally which renders factious combinations less to be dreaded … The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression. Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other … [D]oes the increased variety of parties comprised within the Union [of States], increase this security. Does it, in fine, consist in the greater obstacles opposed to the concert and accomplishment of the secret wishes of an unjust and interested majority? Here, again, the extent of the Union [of States] gives it the most palpable advantage.

The tendency of smaller geographic regions to fall victims to control by factions reflects the modern understanding of “groupthink,” which municipal governmental bodies are particularly prone toward. As the New England Complex Systems Institute, in its “An Introduction to Complex Systems Science and Its Applications,” states:

We began by considering idealized hierarchies with only vertical connections, but lateral connections provide another mechanism for enabling larger-scale behaviors. For instance, cities can interact with one another (rather than interacting only with their state and national governments) in order to copy good policies and learn from each other’s mistakes … Overly strong connections [however] lead to herd-like behaviors with insufficient smaller-scale variation, such as groupthink …”

In the book Making Things Work: Solving Complex Problems in a Complex World, Yaneer Bar-yan of the Institute presents a simple model (much like Nassim Taleb’s example of “renormalization” described in a previous essay) of how a sort of “groupthink” works:

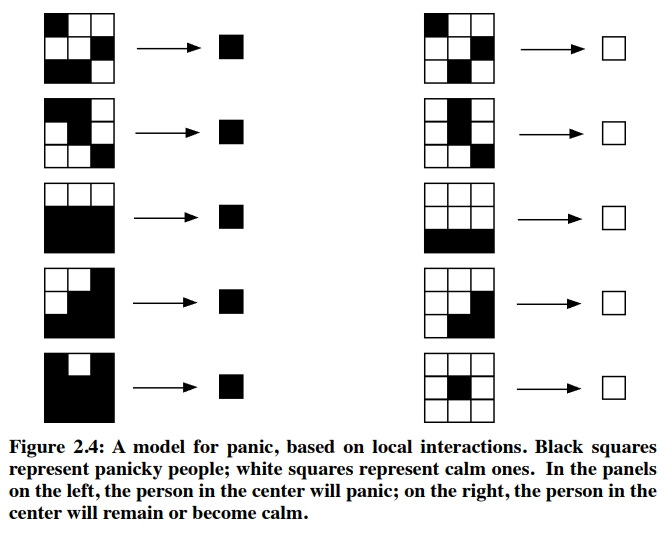

We could also use a model … to think about the spread of panic throughout a room. Consider people sitting in a crowded auditorium. They are aware of the people immediately surrounding them, in the same row and in the rows in front of and behind them. If there are enough people panicking around an individual, he will tend to panic, too, even if he was calm … Each 3x3 panel show the panicky people as black squares and the non-panicky as black squares and the non-panicky people as white squares. If four of the people (count also the middle one) are panicky, then a few moments later the middle one will become panicky. If there are three or fewer, then he doesn’t panic. Even if he himself was initially panicky, he calms down.

As you can see from the figure below, even a room with a majority of calm people can turn into a room of panicky people provided there are enough panicky people adjacent to enough initially calm people.

(As the authors note, “Sometimes behaviors feed on each other and grow to involve many people, and sometimes they don’t. Understanding exactly what leads to the difference can be quite hard, but it definitely has to do with the interactions between people, the conditions under which the people are interacting with each other, and the triggering influence (if any).” This is yet another example of how calculus, and its measurements of rate of change among various factors, can be helpful, even in explaining panic.)

When localities succumb to groupthink, state legislatures, with their exposure to a wider diversity of constituent views, can step in to help balance a policy. Consistent with that Madisonian view, forty of the fifty U.S. states apply some form of the principle known as Dillon's Rule (a concept attributed to John Forrest Dillon, the author of an influential treatise on the power of states over local governments) under which local governments may only exercise powers the individual states expressly grant to them.

The advantage of citizens’ potential resort to state governments in the face of dominant partisan factions in smaller urban and suburban local governments played out recently in Virginia (one of the states governed under the Dillon Rule), where certain local schools boards, dominated by members of one political party in the northern part of the state, refused to ease requirements that kids wear masks in public schools (even as the evidence for the efficacy of those masks to mitigate the spread of disease was weak). In that case, the state legislature overrode the decision of the local school boards by statute, as discussed in a previous essay. As that episode demonstrates, perhaps, just as Madison envisioned, state governments -- as opposed to the local and federal governments -- are the greatest hope for reversing trends toward increased bureaucracy and its diminishing (or negative) marginal returns today.

To see why, we might look again to the researchers at the New England Complex Systems Institute, who describe why the federal top-down approach risks more harm than good in today’s complex society. As they write in “An Introduction to Complex Systems Science and Its Applications”:

To help us think about a hierarchy, it is useful to focus on an idealized hierarchy … In an ideal hierarchy, people only communicate up and down the hierarchy. If you want to do something with someone in the office next door to you, you must first talk to your boss and your boss will then tell your neighbor what to do. If your boss does not supervise your neighbor (or if you want to do something with the person down the hall), your boss must talk to his boss, who in turn will talk to the boss of the person down the hall, who will tell him what to do. Of course, the bosses don’t need to wait for someone in the ranks to suggest an action, they might just decide to tell a bunch of people what to do … We’ve arrived at an important conclusion. Since the large-scale behaviors are communicated through the CEO [or the President, or the head of a federal agency], there is a limit to their complexity – the large-scale behaviors cannot be more complex than the CEO. This complexity is large, as large as a single human being, but it is limited.

The authors go on to describe the limits of adaptability in top-down hierarchies (such as those subject to federal control) compared to hybrid hierarchies (such as a federal system in which states have independent authority), in which some authoritative action is allowed between those lower down the chain on command.

I’ll conclude this series of essays with a comparison made by Yaneer Bar-yan in his book Making Things Work:

Comparing these pictures illustrates the combined issues of complexity and scale in two successful organisms. The legs of a wolf are designed for the largest scale action: moving the animal as a whole. The structure of a person gives up some of the ability to run fast. Only two of the four limbs are for moving the entire organism. The arms and hands are designed for finer scale, higher complexity, manipulations. If the environment requires larger scale motion/action the wolf is better suited for that environment. If the environment requires a finer scale higher complexity manipulation, the person is better suited. This figure therefore demonstrates two key ideas: 1) there is a trade-off between complexity and scale, and 2) the success of the organism/organization depends on both complexity and scale.

The question is: in our complex society today, would we do better under a structure run more by wolves, or by individual human beings?

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5.