How Cancel Culture Works

Or, how an intransigent minority can easily bend the will of a majority initially inclined to be accommodating.

There’s a lot of talk about “cancel culture,” a phenomenon in which a group of people (usually a relatively small group of people) noisily complain about someone, and before you know it the media is reporting on the complaints and the target of the complaints is pressured to resign or otherwise recede from public view (or their employer’s pressured into firing them) simply to make the noisy complaints stop. I was recently reading Nassim Taleb’s book “Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life,” and something he wrote struck me as relevant to that cancel culture phenomenon.

Taleb uses the following example in which only a single person may insist on food that isn’t genetically modified (non-GMO), but soon the world they live in comes to cater exclusively to people who only want to eat non-GMO foods. It works through a process called “renormalization,” like this.

First, picture a world made of social units that are squares, but each square consists of four smaller squares. Taleb then walks through the following scenario:

[This figure] shows four boxes exhibiting what is called fractal self-similarity. Each box contains four smaller boxes. Each one of the four boxes will contain four boxes, and so all the way down, and all the way up until we reach a certain level. There are two shades: light for the majority choice, and dark for the minority one. Assume the smaller unit contains four people, a family of four. One of them is in the intransigent minority and eats only non-GMO food (which includes organic). The color of this box is dark, and the others light.

We “renormalize once” as we move up: the stubborn daughter manages to impose her rule on the four [her family] and the unit is now all dark, i.e., will opt for non-GMO.

Now, step three, you have the family going to a barbecue party attended by three other families. As they are known to only eat non-GMO, the guests will cook only organic.

The local grocery store, realizing the neighborhood is only non-GMO, switches to non-GMO to simplify life, which impacts the local wholesaler, and the system continues to “renormalize” …

This dynamic only happens when the majority inclined to be accommodating initially thinks it will make their life on net easier if they go along and cater to the demands of the smaller group. (Taleb says “Let us call such minority an intransigent group, and the majority a flexible one. And their relationship rests on an asymmetry in choices.”) Non-GMO foods may be a bit more expensive, and there may be fewer choices among non-GMO foods, but eating non-GMO foods when you might prefer GMO foods won’t kill you, and you’ll also avoid having to hear people insisting on non-GMO foods complain when they don’t get their way. So people cave to the smaller group’s preferences, even at the expense of the preferences of the larger group who, feeling an inclination to be accommodating, might not complain as much about life as the smaller group does.

It’s easy to see how this dynamic could work to pressure companies to cater to small groups of unreasonable complainers who say they’re somehow harmed when other people say things that offend them. For example, one person in a group might be offended if someone else uses the term “merit.” (Maybe someone who read “How to Be an Antiracist,” in which Ibram X. Kendi writes “The use of standardized tests to measure aptitude and intelligence is one of the most effective racist policies ever devised.”) And so people in that smaller group stop using that term. And so larger groups that include that group may stop using that term, and so on. Pretty soon nobody’s using the term “merit.” They may still live their life, or parts of it, based on principles of merit, but they won’t use the term around others to avoid offending them and incurring their ire.

The problem, of course, is that pretty soon, if people don’t talk about merit, they may slowly forget its value. Someone may occasionally speak up and remind people of its value, but because the norm of the group is not to speak of it, those people might be pressured to just keep quiet about it. And pretty soon everyone starts censoring themselves to avoid the hassle. And maybe they even internalize the false message that merit is a bad thing and stop acting on that principle in their own lives as well, or even working to get the government to impose policies in which merit is ignored and mediocrity is rewarded. And pretty soon we have something like (as described by Adrian Wooldridge in his book “The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World”):

Maximilien Robespierre and his fellow sans-culottes wanted to take an axe to hierarchy in all its dimensions, including superior knowledge. The Constituent Assembly, which sat from 1789 to 1791, rejected the idea of using examinations to determine selection into the officer corps on the grounds that it would create a “new aristocracy.”

Yup, that was the French Revolution.

As Taleb reminds us, “Let us conjecture that the formation of moral values in society doesn’t come from the evolution of the consensus. No, it is the most intolerant person who imposes virtue on others precisely because of that intolerance. The same can apply to civil rights.”

And as Taleb further reminds us, “people fear being labeled racists so much that they lose their logical faculties.”

Taleb calls this dynamic “That Greatest Asymmetry,” namely:

the minority rule by which a small segment of the population inflicts its preferences on the general population … It suffices for an intransigent minority—a certain type of intransigent minority … to reach a minutely small level, say 3 or 4 percent of the total population, for the entire population to have to submit to their preferences. Further, an optical illusion comes with the dominance of the minority: a naive observer (who looks at the standard average) would be under the impression that the choices and preferences are those of the majority. If it seems absurd, it is because our scientific intuitions aren’t calibrated for this.

Taleb recounts various examples of this dynamic in real life:

“The kosher population represents less than three tenths of a percent of the residents of the United States. Yet, it appears that almost all drinks are kosher. Why? Simply because going full kosher allows the producers, grocers, and restaurants to not have to distinguish between kosher and nonkosher for liquids, with special markers, separate aisles, separate inventories, different stocking sub-facilities. And the simple rule that changes the total is as follows: A kosher (or halal) eater will never eat nonkosher (or nonhalal) food, but a nonkosher eater isn’t banned from eating kosher.”

“Another example: do not think that the spread of automatic shifting cars is necessarily due to a majority preference; it could just be because those who can drive manual shifts can always drive automatic, but the reverse is not true.”

“All it takes is, say, a 3 percent minority, for “Merry Christmas” to become ‘Happy Holidays.’”

I’d add to this list a dynamic that works in Congress as a sort of “government expansion culture,” in the following way. Democrats generally support spending lots more money on everything. Republicans generally support either spending no more money or some more money, but not as much as Democrats want to spend. Because on net even Republicans are willing to go along with spending at least some more money (to avoid appearing mean), the result is that, even if there’s a “bipartisan” compromise on spending, the government will still always end up spending more money.

As I’ve written previously, people should develop the skill of not letting things other people say bother them, if only to improve their own well-being. But there will always be unreasonably sensitive people. And generally, the small intransigent groups of unreasonably sensitive people probably haven’t gotten any more numerous today than they were in the past. The difference today, however, is that the intransigent small groups have gained the ability to promulgate their intransigent views much more widely, thanks to social media. As researchers Michael Bang Petersen and Alexander Bor reported recently in the Washington Post:

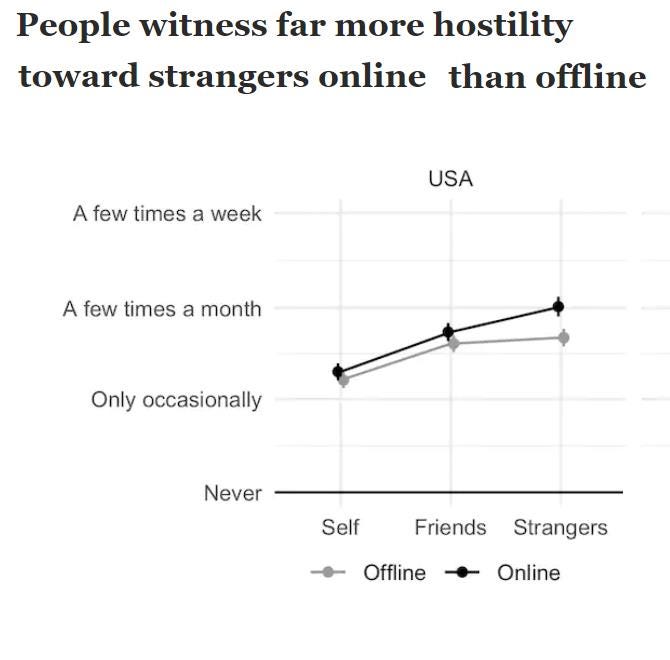

The big difference between online and offline discussions is that we witness a lot more acts of hostility online, not so much against ourselves or our friends, but against strangers (see figure). Our surveys asked Danes and Americans in 2019 how often they are offended and how often they witness offenses against their friends and against strangers, offline and online. In other words, the Internet doesn’t stir up hostility. Instead it creates and facilitates what we call “connectivity” among groups with shared politics, and between trolls and their victims. It allows individuals who are predisposed to be hostile to accomplish their goals more effectively.

So it’s not that people have gotten significantly more hostile, just that those doing the complaining can now propagate their complaints more widely – they can broadcast them “far and whine.” And being able to do that, they can rapidly make the whole world their neighborhood (and replicate nationwide the effects of Taleb’s non-GMO example discussed earlier).

Taleb isn’t very optimistic. He writes, “Yes, an intolerant minority can control and destroy democracy. Actually, it will eventually destroy our world.” But I doubt that’s true. Maybe all it would take to make things better would be for another minority of people to simply understand the perverse results of this dynamic, and explain it to others. That, and some courage.

Thank you. Another good explanation!