Continuing our exploration of data on religion and culture, there are many indications that while religiosity may be decreasing among the population, the relatively greater propensity of the religious to get married and have children may end up boosting religiosity in the long run.

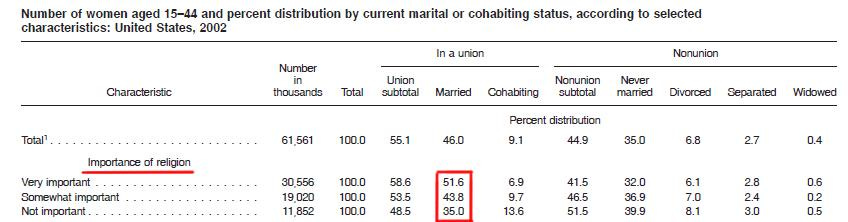

The more religious one is, the more likely one is to be married.

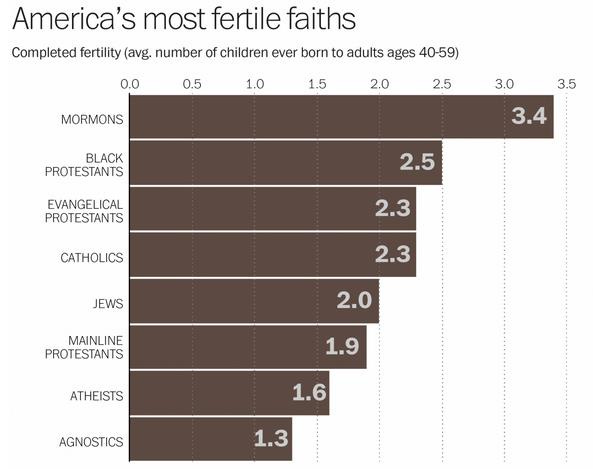

And the more religious one is, the more likely one is to have children:

In their international comparisons of fertility rates, Pipa Norris and Ronald Inglehart find modern-day societies that are more religious have more children than secular societies, even when countries are matched on national income and education levels. Moreover, when fertility rates are plotted over time within the same country, we find the same story: as religiosity declines in a society over the years (reflecting the secularization trend that has occurred in much of Western and Eastern Europe in the second half of the twentieth century), so do fertility rates. Despite strong government incentives in welfare-state countries such as France and Germany to combat low fertility rates, it is hard to find counterexamples. Michael Blume explains: “Although we looked hard at all available data and case studies back to early Greece and India, we still have not been able to identify a single case of any non-religious population retaining more than two births per woman for just a century. Wherever religious communities dissolved, demographic decline followed suit.”

A Pew survey shows how much more fertile various religious denominations are compared to the non-religious.

Worldwide, Muslims have the highest birth rates.

A 2018 literature review found that several components of religious involvement (self-control and the desrire for socialization) reduce the likelihood of criminal behavior and significantly decrease binge drinking, marijuana use, and dependence on hard drugs over time. And these effects are also shown among people who are already drug offenders. Religion also has a deterrent effect on crime.

Religion is also positively associated with self-control generally, with researchers stating “there is strong evidence for our proposition that religion is positively related to self-control as well as to traits such as Agreeableness and Conscientiousness that are considered by many theorists to be the basic personality substrates of self-control … There is also substantial evidence that religious parents tend to have children with high self-control.”

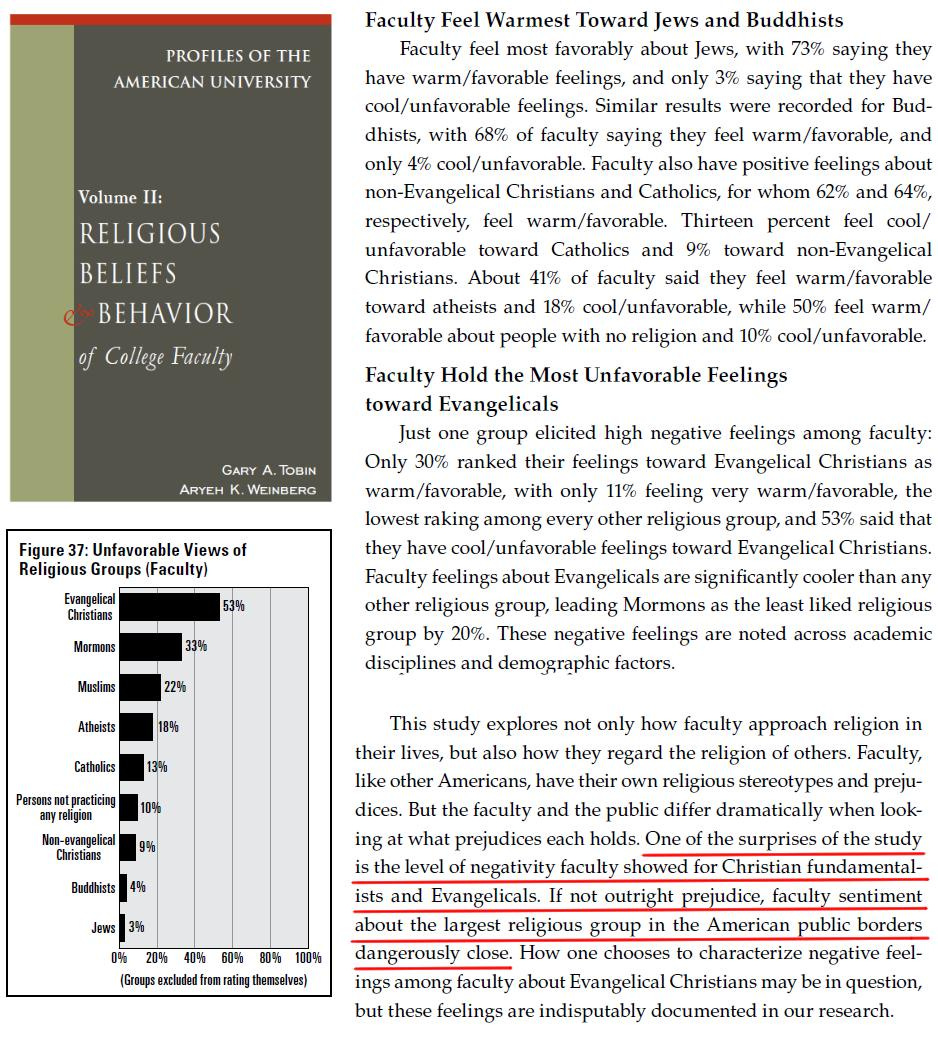

Yet, according to the President of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, evangelical Christian groups are among the most discriminated against on college campuses:

While it sometimes seems like there is no rhyme or reason to what can get a student group in trouble on campus, certain trends emerge over time—in particular, the fundamental misunderstanding of tolerance and freedom of association that is widely applied to evangelical Christian groups. If you told me twelve years ago that I, a liberal atheist, would devote a sizeable portion of my career to defending Christian groups, I might have been surprised. But almost from my first day at FIRE, I was shocked to realize how badly Christian groups are often treated. Whether I personally believe in God or not, I certainly believe in the right to follow the faith that you choose. When I talk about this issue, I often get a lot of pushback: surely the idea that evangelical Christians are disfavored on college campuses is just some kind of right-wing propaganda, and the examples that I cite are just weird flukes, people say. Given my experience, however, I was not at all surprised when a 2007 study of attitudes about religion among faculty performed by the Institute for Jewish and Community Research showed that evangelical Christians were the only group that a majority of faculty were comfortable to admit evoked strong negative feelings in them. The study also revealed that Jews and Buddhists were the two groups that faculty members felt the most positive about. They also reported positive feelings about Muslims but fairly negative about Mormons.

That survey conducted by the Institute for Jewish and Community Research showed that evangelical Christians were the only group that a majority of faculty were comfortable admitting evoked strong negative feelings in them:

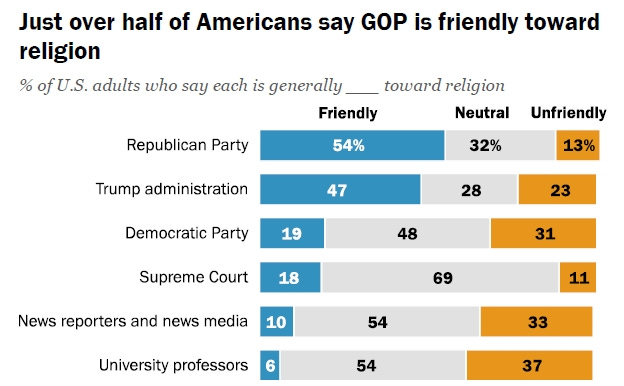

Politically, of the two major political parties, the media, and university professors, only the Republican Party is generally considered more friendly toward religion.

A November 2019 Pew survey found an even greater gap in the perceived friendliness of the political parties toward religion.

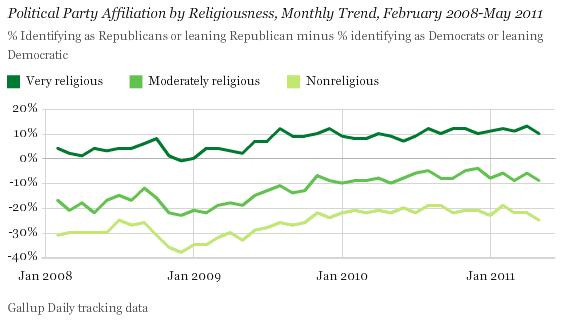

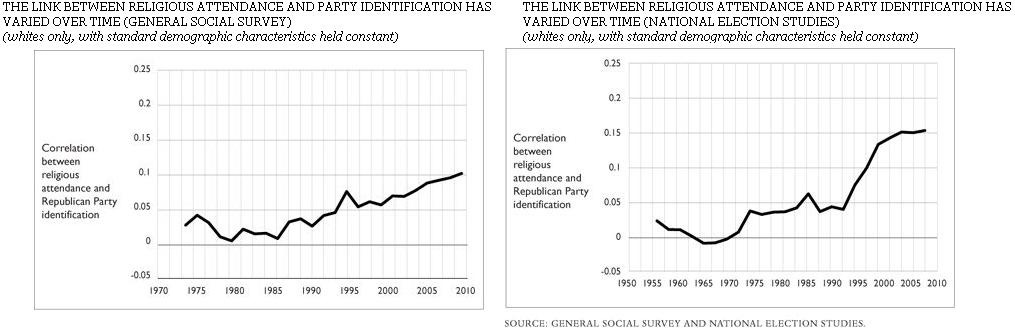

And those who are most religious tend to identify most with the Republican Party.

The most prominent religious groups in America and their political affiliations as a group are listed below.

There is a growing religious gap between the two major political parties. A 2019 survey by Gallup finds that membership in religious congregations is plummeting. Only half (50%) of the public report that they are a member of a house of worship -- church, synagogue or mosque. Just five years earlier, nearly six in ten (59%) Americans said they were a member of a religious congregation. The drop marks the first time in the history of Gallup’s polling, which stretches back to 1938, that fewer than a majority of the public reported belonging to a religious congregation. The disparity in church membership between Democrats and Republicans is stark. In the late 1990’s, more than seven in ten Democrats (71%) and Republicans (77%) said they belonged to a congregation. More recently, fewer than half (48%) of Democrats are members of a church, synagogue or mosque while 69% of Republicans are.

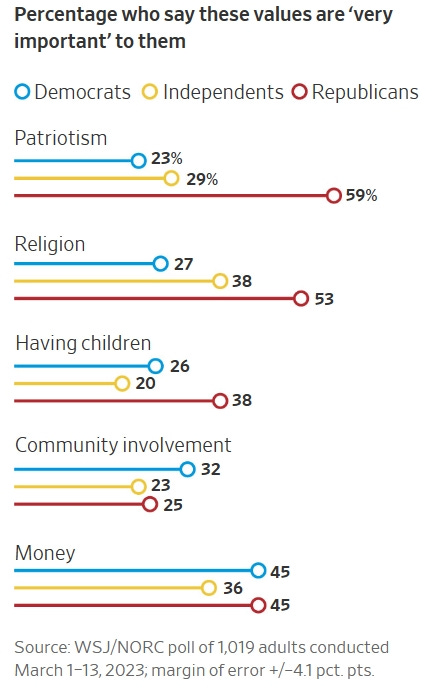

A March, 2023, survey conducted by the Wall Street Journal and the University of Chicago found falling support generally for the values of “patriotism,” “religion,” and “having children,” but also that people who politically identified as Republicans were much more likely to support those values than Democrats or Independents.

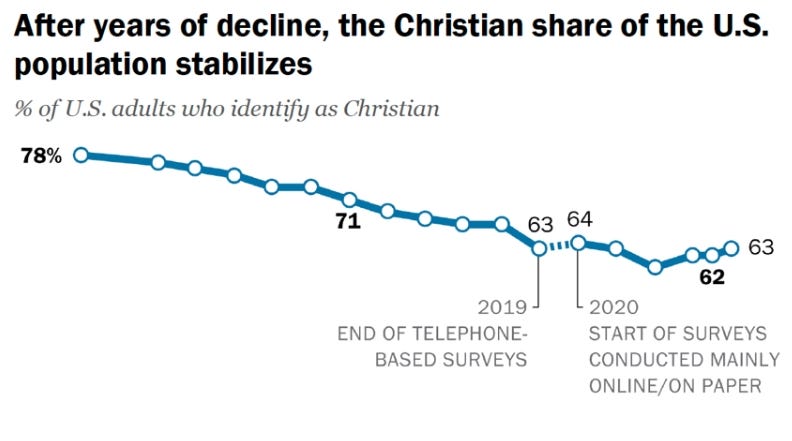

As of 2024, the Pew Researcg Center found that the decline of Christianity in the U.S. had slowed, and may have even leveled off.

In the next series of essays, we’ll examine the concept that has been dubbed the “Puritan work ethic” and its impact on industriousness over time.

And here I thought it was the meek. Love learning something every time I read what you have written. Continuing thanks.