In this series of essays, we’ll look at some general statistics regarding religion and culture.

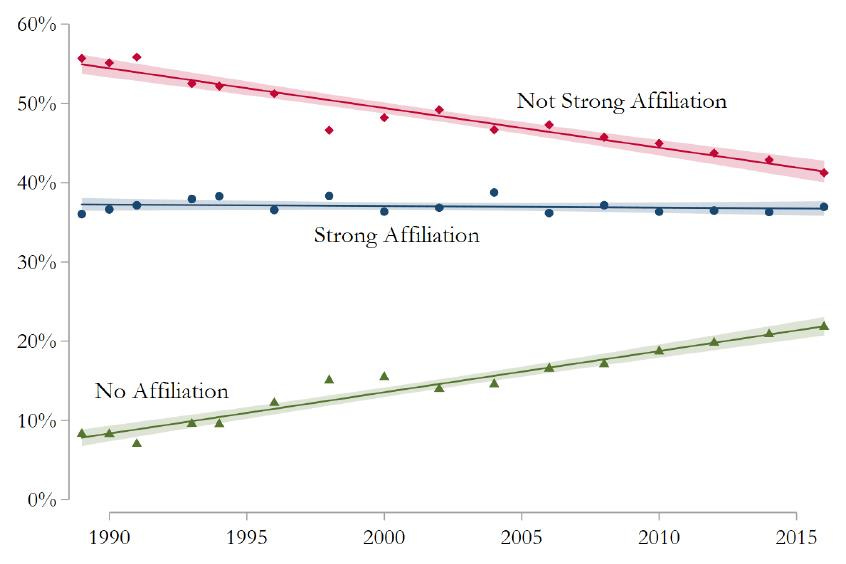

While there has been an increase in the percentage of Americans without religious affiliations or with weak affiliations, the percentage of Americans with strong religious affiliations and who pray multiple times a day has tended to remain steady in recent decades.

Religiosity is also generally associated with better health. A 2019 study found that attendance at religious services (at least once a week) shows a strong and consistent association with life and health expectancy. Researchers at the Mayo Clinic have also concluded, “Most studies have shown that religious involvement and spirituality are associated with better health outcomes, including greater longevity, coping skills, and health-related quality of life (even during terminal illness) and less anxiety, depression, and suicide. Several studies have shown that addressing the spiritual needs of the patient may enhance recovery from illness.”

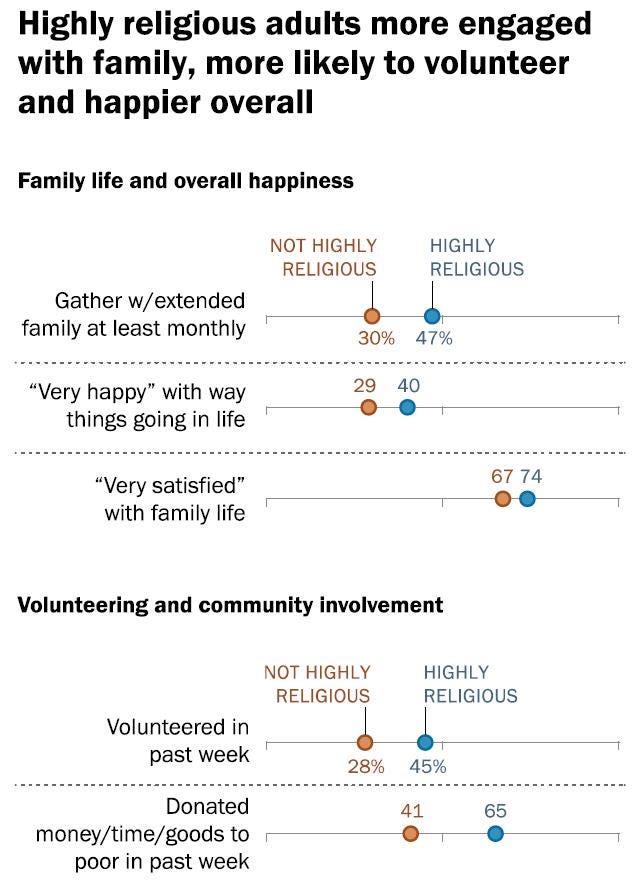

A 2016 Pew survey found that highly religious people are more engaged with family, more likely to volunteer, and happier overall.

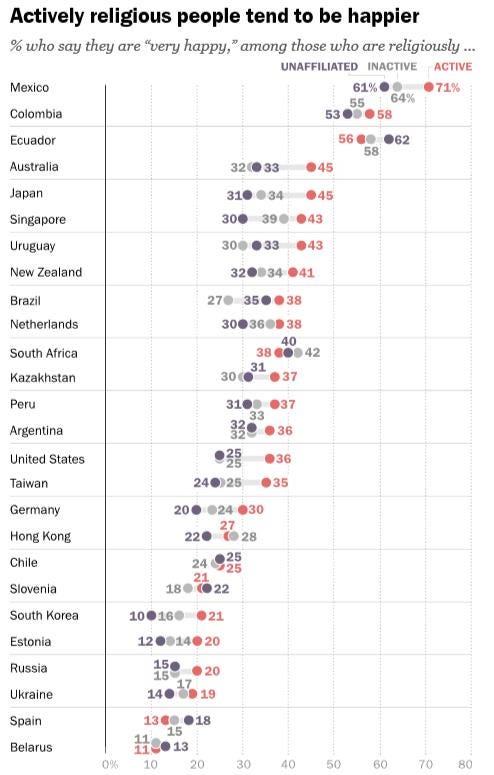

A literature survey in The Science of Subjective Well-Being found that “In survey after survey, actively religious people have reported markedly greater happiness and somewhat greater life satisfaction than their irreligious counterparts.” And as Tyler VanderWeele at the Harvard School of Public Health writes:

A major 2022 systematic review in the Journal of the American Medical Association documented 215 studies, each with sample sizes over 1,000 participants, using longitudinal data to evaluate the relationship between religion and health. The evidence from meta-analyses, large longitudinal studies (including from Harvard’s own Nurses’ Health Study), and handbooks providing more extensive documentation, suggests that weekly religious service attendance is longitudinally associated with lower mortality risk, lower depression, less suicide, better cardiovascular disease survival, better health behaviors, and greater marital stability, happiness, and purpose in life. Whether religion is a cause or just a correlate for such improvements has been an important consideration in these studies, which control for baseline health and adjust also for numerous other social, economic, and behavioral confounding variables. They are robust in sensitivity analysis, and they obtain large effect estimates—results that provide strong evidence for attendance being a cause. The number and quality of studies supporting these conclusions has steadily grown and the evidence base is now very compelling. Religion should not be neglected as a social determinant of health.

Actively religious people around the world tend to be happier.

Researchers have found that religiosity among adolescents dramatically decreases their incidence of depression:

Depression is the leading cause of illness and disability in adolescence. Many studies show a correlation between religiosity and mental health, yet the question remains whether the relationship is causal. We exploit within-school variation in adolescents’ peers to deal with selection into religiosity. We find robust effects of religiosity on depression that are stronger for the most depressed. These effects are not driven by the school social context; depression spreads among close friends rather than through broader peer groups that affect religiosity. Exploration of mechanisms suggests that religiosity buffers against stressors in ways that school activities and friendships do not … [A] one standard deviation increase in religiosity decreases the probability of being depressed by 11 percent. By comparison, increasing mother’s education from no high school degree to a high school degree or more only decreases the probability of being depressed by about 5 percent.

As Harvard professor Robert Putnam describes the positive effects of religion on young people:

In addition to philanthropy and good works, religious involvement among youth themselves is associated with a wide range of positive outcomes, both academic and nonacademic. Compared to their unchurched peers, youth who are involved in a religious organization take tougher courses, get higher grades and test scores, and are less likely to drop out of high school. Controlling for many other characteristics of the child, her family, and her schooling, a child whose parents attend church regularly is 40 to 50 percent more likely to go on to college than a matched child of nonattenders. Churchgoing kids have better relations with their parents and other adults, have more friendships with high-performing peers, are more involved in sports and other extracurricular activities, are less prone to substance abuse (drugs, alcohol, and smoking), risky behavior (like not wearing seat belts), and delinquency (shoplifting, misbehaving in school, and being suspended or expelled). As with mentoring, religious involvement—when it happens—makes a bigger difference in the lives of poor kids than rich kids, in part because affluent youth are more exposed to other positive influences.

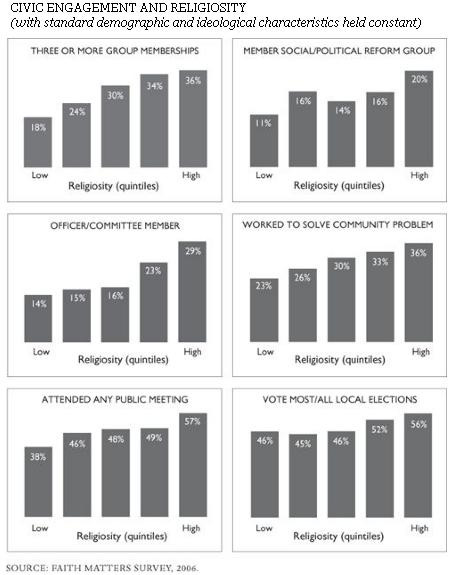

Religiosity is also associated with more civic engagement.

Researchers have found that “disbelievers (vs. believers) are less inclined to endorse moral values that serve group cohesion (the binding moral foundations),” namely the Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity moral foundations that protect the integrity of the group.

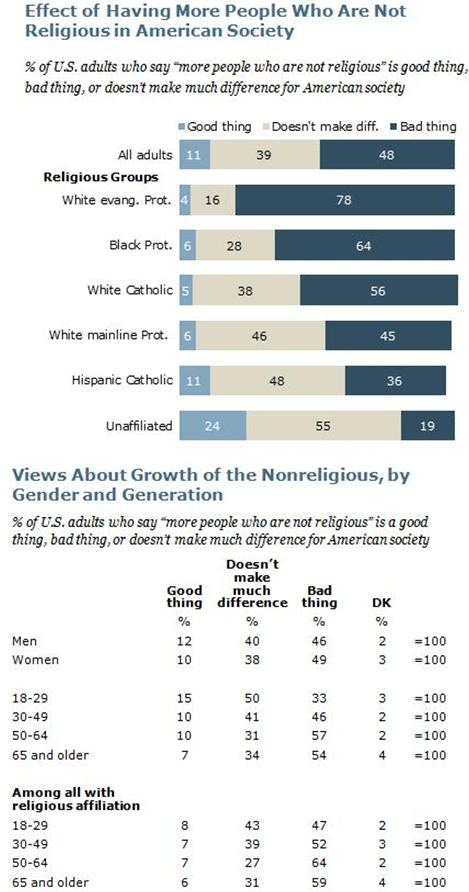

Even among people who are unaffiliated with a religion, only 24 percent say “more people who are not religious” is a good thing. Among other groups, a majority or a plurality say “more people who are not religious” is a bad thing.

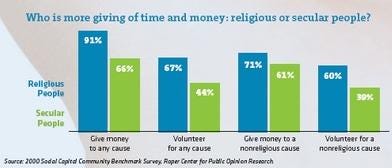

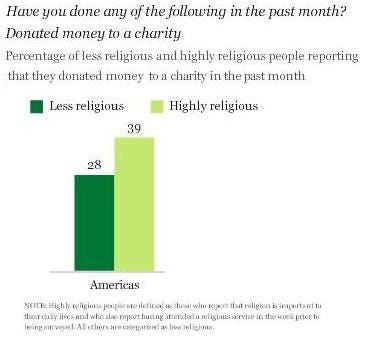

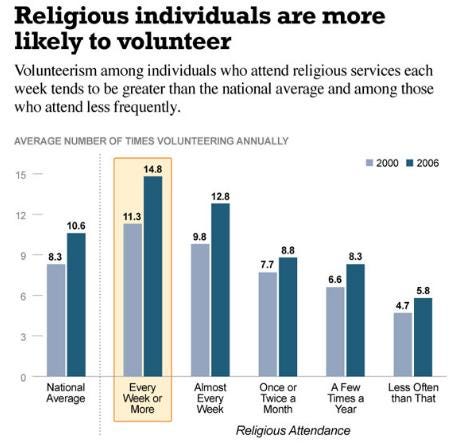

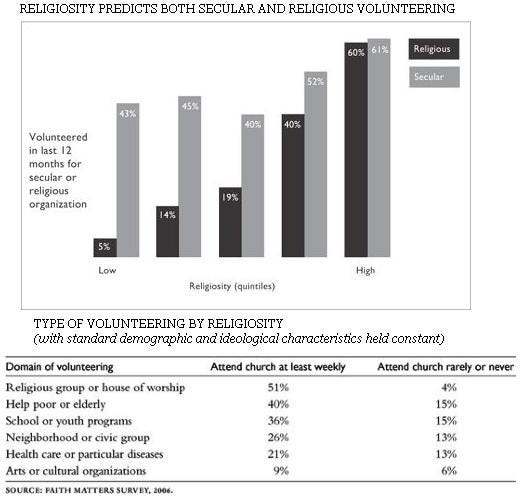

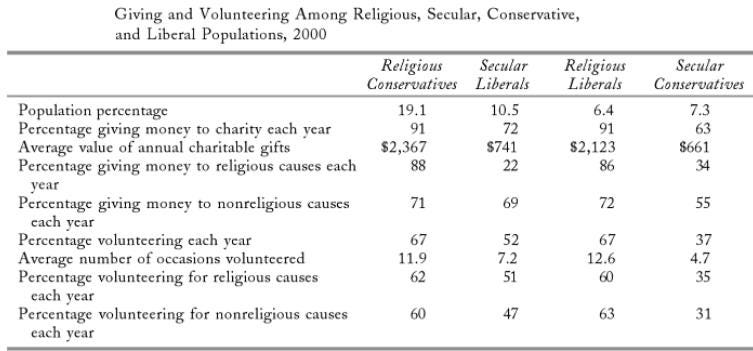

Other research also shows that it is religious people who are most likely to give to charities and volunteer.

Religiosity is associated with more volunteering for both religious and secular causes.

Along a variety of charitable dimensions, religious people tend to be significantly more charitable (including being more likely to donate blood, food, or money, and to express empathy for the less fortunate) than non-religious people.

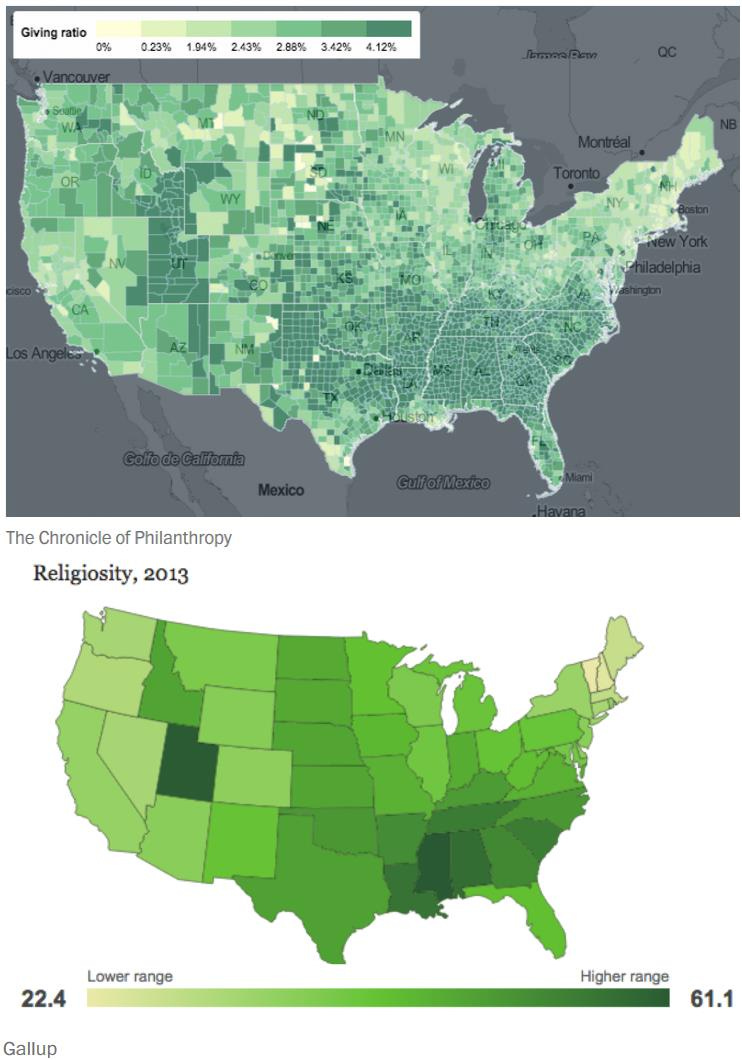

Regions of the country that are more religious also give more to charity. In the maps below, the darker the green, the more religious and the more charitable the area.

While religiosity is associated with more charitable giving, increased government spending is associated with less. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis determined that “a long-run negative relationship does exist between charitable giving and government spending,” as increasingly larger government benefit programs crowd out private charitable giving generally. As the federal government takes more of what people earn and claims more responsibility for more people’s well-being, religious people, along with all other people, have less to spend on private charities.

Higher tax rates also result in less charitable giving.

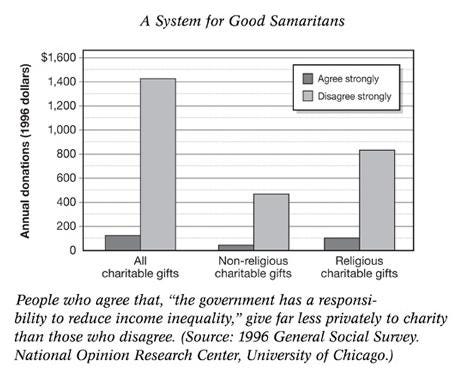

People (regardless of religion) who agree that “the government has a responsibility to reduce income inequality” give far less to private charity than those who disagree.

Religious people in America tend to support a smaller government providing fewer services.

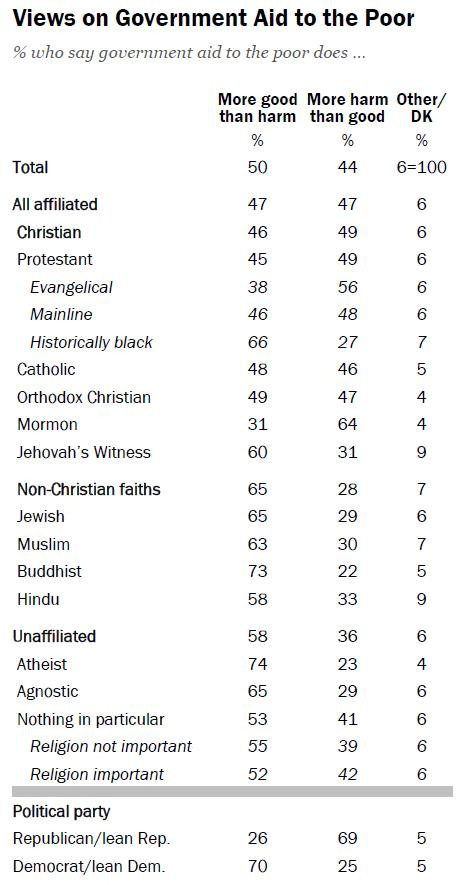

Religious people in America also tend to say that government aid to the poor does more harm than good.

People in countries with larger welfare states are less religious, as they tend to look to the state rather than to a higher power (or to other people who may be inspired by a higher power) for support and stability. Western countries with the largest welfare states tend to be those with the fewest religious people. Researchers have found that:

Churches historically have provided social welfare. As governments gradually assume many of these welfare functions, individuals with elastic preferences for spiritual goods will reduce their level of participation since the desired welfare goods can be obtained from secular sources. Cross-national data on welfare spending and religious participation show a strong negative relationship between these two variables after controlling for other aspects of modernization … It is quite apparent that there is a strong [negative] statistical relationship between state social welfare spending and religious participation and religiosity. Countries with higher levels of per capita welfare have a proclivity for less religious participation and tend to have higher percentages of non-religious individuals. People living in countries with high social welfare spending per capita even have less of a tendency to take comfort in religion, perhaps knowing that the state is there to help them in times of crisis … [T]here is likely a substitution effect for some individuals between state-provided services and religious services.

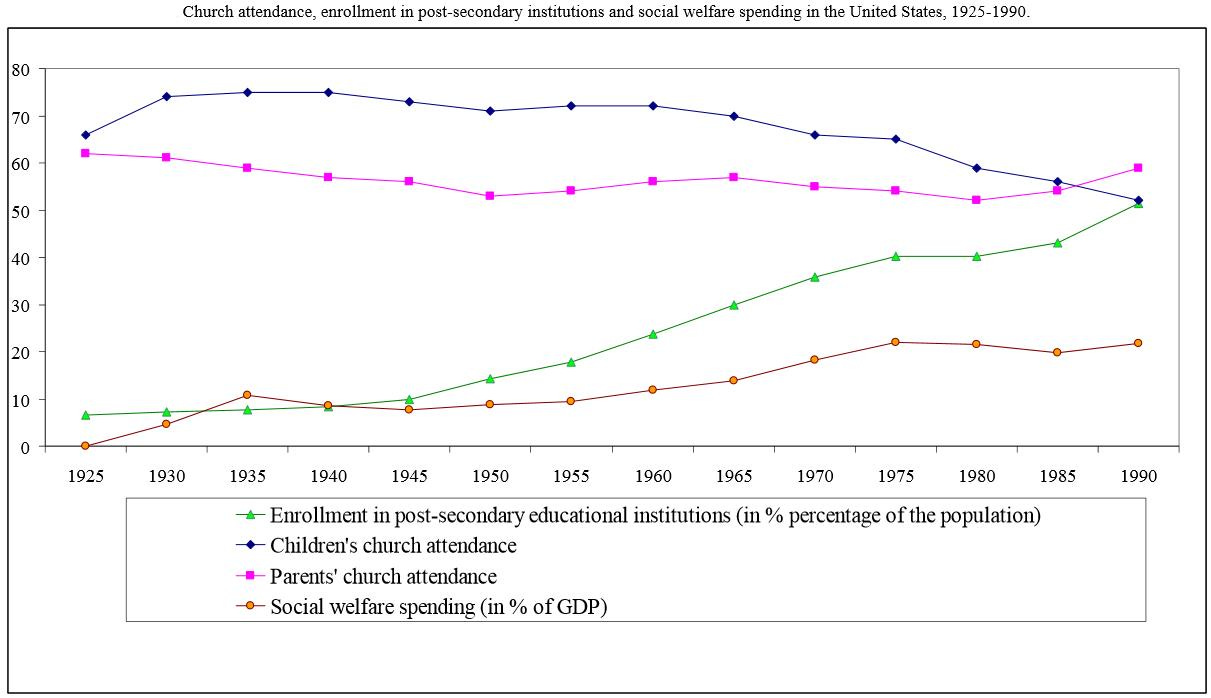

In the United States, church attendance has gone down while government benefits spending has gone up.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore data indicating the religious may inherit the Earth (demographically speaking).