Data on Discrimination Against Women – Part 2

College major preferences and STEM fields, as they relate to gender.

In this essay, we’ll look at data on college major preferences and the various scientific fields, as they relate to gender.

College Majors and Graduate Studies

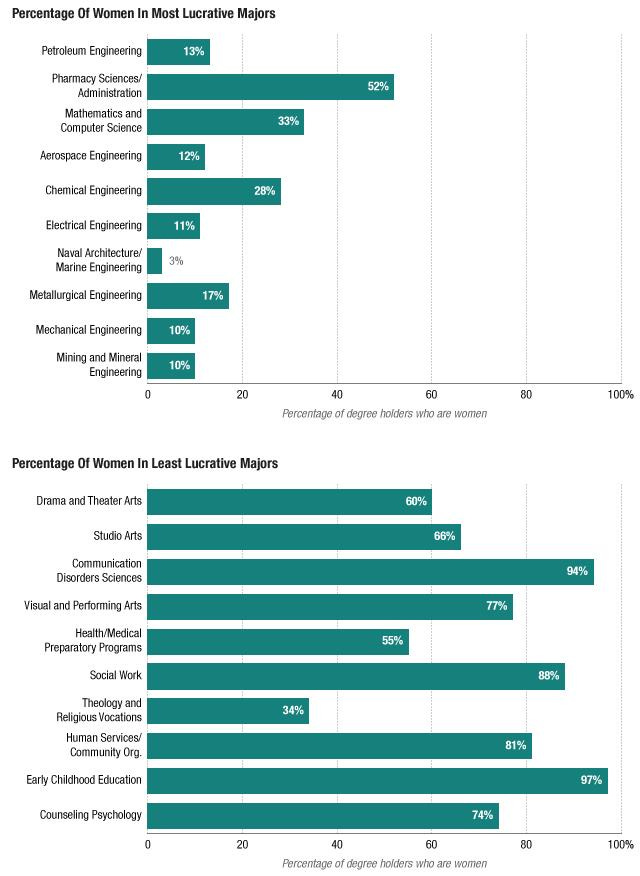

As was described in a previous essay, there are stark gender gaps favoring girls in K-12 education, and also large disparities in favor of women college and graduate school attendance. But while women attend college at much greater rates than men, women also tend to choose the least lucrative majors in college.

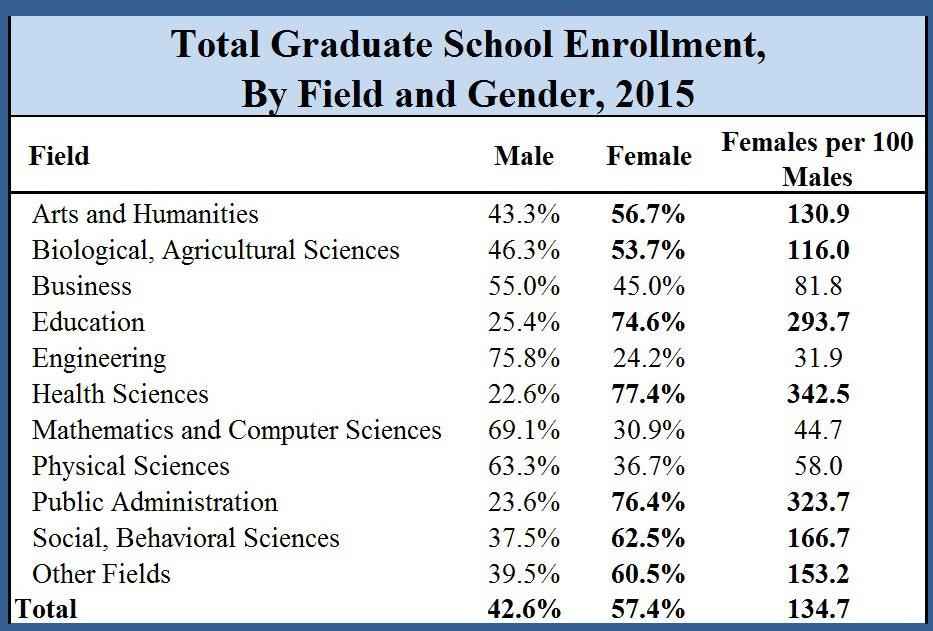

By field of study, women enrolled in graduate school outnumber men in 7 out of 11 graduate fields studied, with females being a minority share of graduate students in only Business (45% female), Engineering (24.2% female), Math and Computer Science (30.9% female), and Physical Sciences (36.7% female), which are also some of the most lucrative majors.

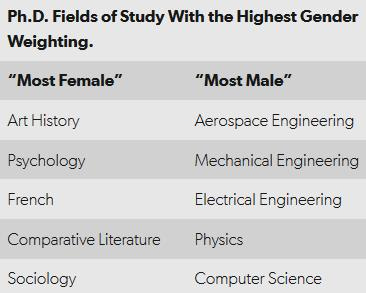

The most gender-imbalanced majors are as follows:

Women in STEM Fields

Overall, women obtain more degrees in STEM fields than do men, when the category of science fields is defined more comprehensively to include biology, medicine, and health.

Steven Pinker, in his book The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature, notes that

a set of studies conducted by the psychologists Wendy Williams and Stephen Ceci … analyzed a number of datasets on gender discrimination in interviewing and hiring professors and in grant and manuscript reviewing. Not only did they find little evidence for discrimination, but in new studies that used the gold standard for testing for prejudice—gatekeepers’ responses to fake résumés—they reported that “men and women faculty members from all four fields [biology, engineering, economics, and psychology] preferred female applicants 2:1 over identically qualified males”—a prejudice opposite in direction to the one that could explain female under-representation in STEM fields.

Researchers have also found that in countries where women are more free to study what they want, inherent gender differences in expressed preferences in fields of study are more prominent:

We investigated sex differences in 473,260 adolescents’ aspirations to work in things-oriented (e.g., mechanic), people-oriented (e.g., nurse), and STEM (e.g., mathematician) careers across 80 countries and economic regions using the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). We analyzed student career aspirations in combination with student achievement in mathematics, reading, and science, as well as parental occupations and family wealth. In each country and region, more boys than girls aspired to a things-oriented or STEM occupation and more girls than boys to a people-oriented occupation. These sex differences were larger in countries with a higher level of women’s empowerment. We explain this counter-intuitive finding through the indirect effect of wealth. Women’s empowerment is associated with relatively high levels of national wealth and this wealth allows more students to aspire to occupations they are intrinsically interested in. Implications for better understanding the sources of sex differences in career aspirations and associated policy are discussed.

The researchers:

found that countries with high levels of gender equality have some of the largest STEM gaps in secondary and tertiary education; we call this the educational-gender-equality paradox. For example, Finland excels in gender equality, its adolescent girls outperform boys in science literacy, and it ranks second in European educational performance. With these high levels of educational performance and overall gender equality, Finland is poised to close the STEM gender gap. Yet, paradoxically, Finland has one of the world’s largest gender gaps in college degrees in STEM fields, and Norway and Sweden (see those three countries on the chart [below]), also leading in gender-equality rankings, are not far behind (fewer than 25% of STEM graduates are women). We … show that this pattern extends throughout the world, whereby the graduation gap in STEM increases with increasing levels of gender equality.

As explained by one of the researchers:

when it comes to their relative strengths, in almost all the countries boys’ best subject was science, and girls’ was reading. That is, even if an average girl was as good as an average boy at science, she was still likely to be even better at reading. Across all countries, 24% of girls had science as their best subject, 25% of girls’ strength was math, and 51% excelled in reading. For boys, the percentages were 38% for science, 42% for math, and 20% for reading. And the more gender-equal the country, as measured by the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index, the larger this gap between boys and girls in having science as their best subject. The gap in reading “is related at least in part to girls’ advantages in basic language abilities and a generally greater interest in reading; they read more and thus practice more,” Geary told me. What’s more, the countries that minted the most female college graduates in fields like science, engineering, or math were also some of the least gender-equal countries. They posit that this is because the countries that empower women also empower them, indirectly, to pick whatever career they’d enjoy most and be best at.

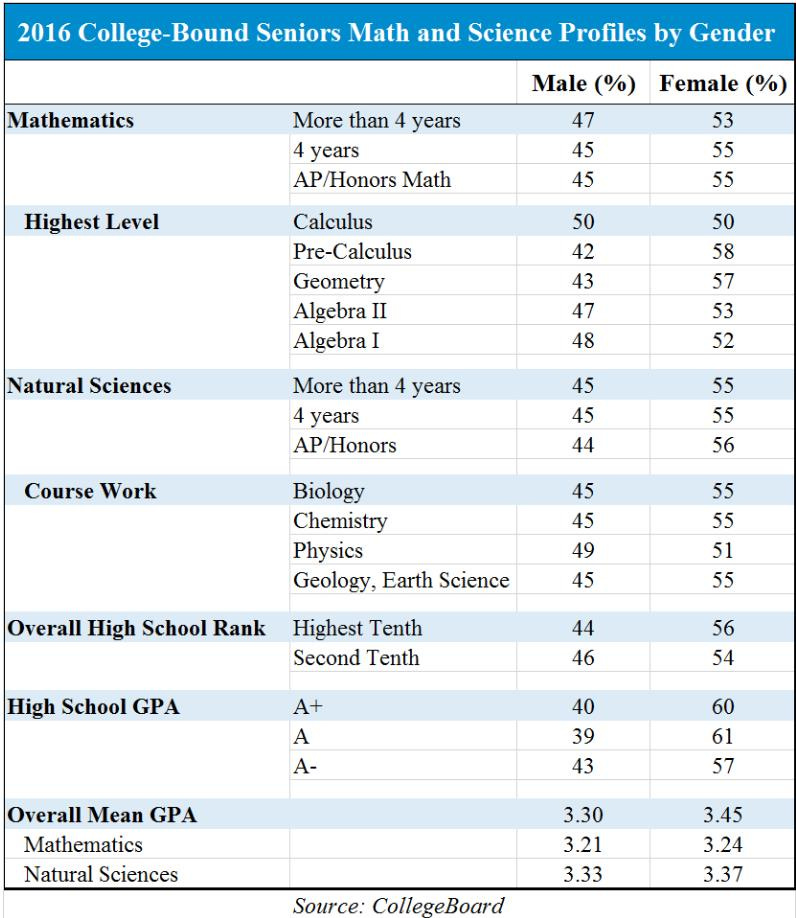

As the chart below shows, at the high school level, girls take more math and science classes than boys, they take more AP and honors classes than boys, they earn higher grade point averages overall, and in math and science courses, and they are far more likely to graduate in the top 10% (and top 20%) of their high school classes.

However, as Mark Perry explains, high school boys have consistently outperformed their female counterparts on the Math SAT test for the last 50 years going back to the 1960’s, and that

Further, for perfect scores (800 points) or near-perfect scores (750 to 790 points) high school boy in 2015 (most recent year available) outnumbered girls by a ratio of almost 2-to-1, providing evidence that there are a lot more boys than girls at the very highest levels of math aptitude. This could be one reason that females are under-represented for some STEM degrees and careers (with notable exceptions like biology, nursing science, zoology, pharmacy and veterinary medicine), especially the most quantitative fields like chemistry, mechanical engineering, and computer science.

Thanks for this. I will save it in my archives for future reference when debating these related issues.

Is there any theory for the obvious confusing conflict with the college-bound math and science outcomes and the SAT outcomes? That does not make much sense to me. I do see with the political left a movement to eliminate SAT in college admissions.