Before starting this essay, I’d like you to watch the following video. It shows a peg board that allows lots of tiny ball to drop down from the top, with each ball winding its way down the array of pegs until they each fall into a bin at the bottom of the board.

As you can see, when the balls fall down, most of them end up near the center of the array of bins at the bottom. That’s no surprise, because as the balls drop further down, they’re less likely to end up falling really far to the left or really far to the right. Most end up in the middle. That is, most of the balls on average fall a little bit to the left or right of each peg as they work their way down. Only a relatively fewer number of balls end up making consistently large jumps to either the left or the right, and those end up at the far ends of the bins at the bottom of the peg board.

Now, since most of the balls end up in the middle of the bins, and only a relatively few end up at the far ends of the bins, the resulting shape of the stacked balls is called a “Bell Curve,” because it’s shaped like a bell. And we find in life that lots of distributions of things fall into this “Bell Curve” shape. For example, if each ball represented a person, and each bin at the bottom represented each person’s height, then we’d find (as we do in real life) that a relatively few number of people are very short or very tall (the far ends of the bins) and most people are of average height (the large middle portion of the bins). Same thing with academic ability. If each ball represented a person, and each bin at the bottom represented each person’s intelligence (however measured), then we’d find (as we do in real life) that a relatively few number of people are not smart, a relatively few number of people are really smart (the far ends of the bins), and most people are of average smarts (the large middle portion of the bins).

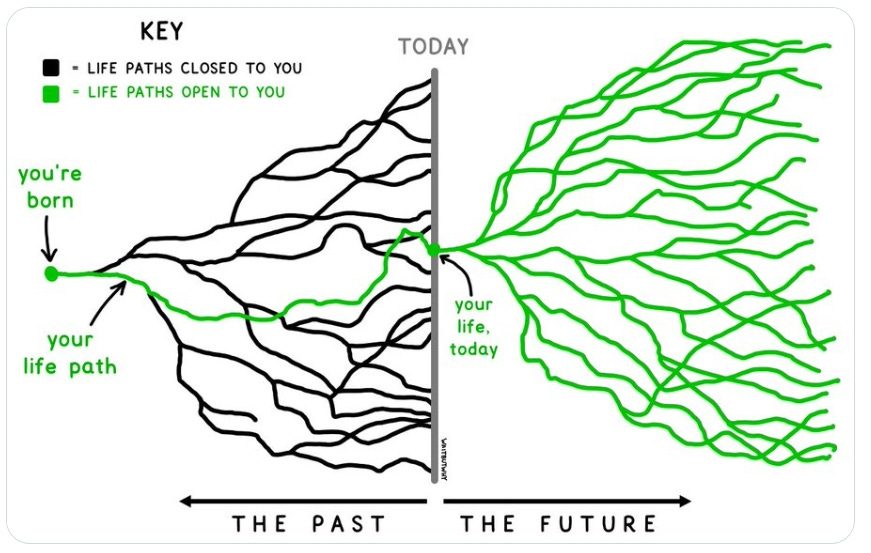

Life is like a giant peg board when it comes to people’s life choices as well. Indeed, one popular representation of the impact of one’s choices in life is this graphical meme, which is essentially the peg board turned on its side:

If you imagine you’re one of the falling balls, but one with free will, then you wouldn’t be a slave to gravity. You’d have the ability to make choices, and to shunt yourself to one side or the other of each peg, based on your choices, as you worked your way down. You don’t have total control of your life, so you couldn’t so easily move to the left or right of every peg (you might have various constraints on your ability to do so at each point), but generally you would have some ability to choose.

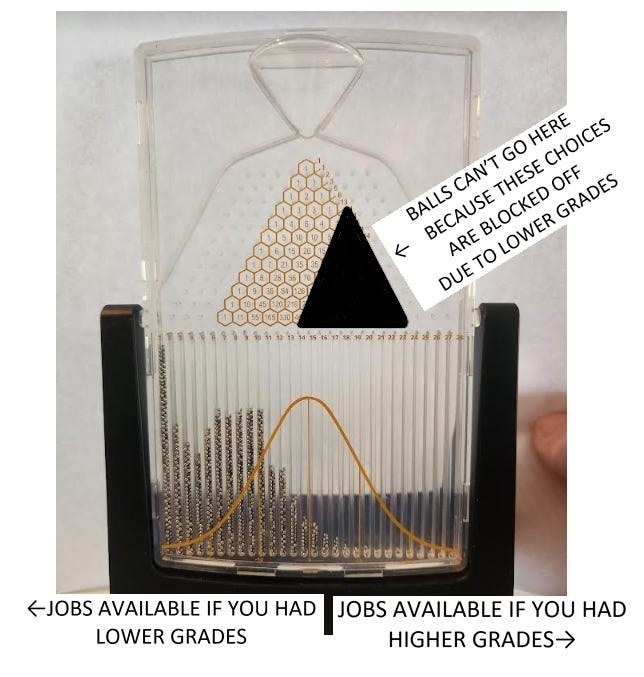

Now, there are some choices in life that would end up foreclosing a large number of options going forward (or downward if you’re on the peg board). For example, you might not do your homework, and get poor grades as a result, which would then limit your job opportunities going forward, and thereby block out from your reach a lot of the pegs from the board on the “needs to have had good grades for this job” side. As a result, you’d end up in one of the bins on the left side at the bottom, where all the job options are for people who didn’t have high grades.

Now, some people see the peg board of life as tilted one way or another, due to “systemic racism,” which deposits the victims of “systemic racism” on only one side of the array of distribution outcomes, like this:

That’s a generally false view of life, since racial disparities among a variety of outcomes are much better explained by things other than racism, but many people hold that view nevertheless.

The other explanation of where people end up on any given peg board of life relates largely to their life choices, and it might look something like this:

In real life, the paths of those balls can be shunted to one side or another based on real choices. If a student doesn’t study, and gets bad grades as a result of failing to demonstrate competence in many subjects, a whole host of paths down one side of the board (the paths that require competence in those subjects) will be foreclosed to them. And various paths will be foreclosed or opened based on thousands upon thousands of other decisions, all involving individual choice and agency.

When different people – including different people within different groups sorted by race – make different decisions, in disproportionate ways, then the balls representing the people who make those decisions are going to end up in disproportionate places on the curve. While a few people’s racist attitudes or behaviors could be closing or shortening some paths for some people, there are many, many other life paths that are the result of an individual’s choices, not external forces.

As Thomas Sowell points out in his book Discrimination and Disparities, it’s statistically inevitable that when you group people together in different ways, including by race, those groups aren’t going to have equal outcomes (as a group). For example, if you need to meet three criteria to achieve a certain outcome, and your chances of meeting all three of those criteria are 2/3 (or 66%), then your chance of achieving that outcome is 2/3 times 2/3 times 2/3, which equals to 8/27. But say one group – for reasons having nothing to do with racism -- has only a one-third chance of meeting one of those criteria instead of two-thirds. Then that group’s chance of achieving a given outcome would be 1/3 times 2/3 times 2/3, which equals 4/27. That’s half the odds of achieving the outcome simply because the odds of meeting one of the criteria dropped from 2/3 to 1/3.

As Sowell explains, “What does this little exercise in arithmetic mean in the real world? One conclusion is that we should not expect success to be evenly or randomly distributed among individuals, groups, institutions or nations in endeavors with multiple prerequisites.”

To increase all students’ chances of achieving success in the real world, schools might consider teaching basic techniques for self-regulation. One study employed a teaching technique with first graders called “mental contrasting,” in which one decides a goal they want to achieve, imagine what it would feel like to obtain that goal, imagine obstacles that might prevent one from achieving the goal, and make an implementation decision about how to achieve the goal. The researchers found that:

Children’s self-regulation abilities are key predictors of educational success and other life outcomes such as income and health. However, self-regulation is not a school subject, and knowledge about how to generate lasting improvements in self-regulation and academic achievements with easily scalable, low-cost interventions is still limited. Here we report the results of a randomized controlled field study that integrates a short self-regulation teaching unit based on the concept of mental contrasting with implementation intentions into the school curriculum of first graders. We demonstrate that the treatment increases children’s skills in terms of impulse control and self-regulation while also generating lasting improvements in academic skills such as reading and monitoring careless mistakes. Moreover, it has a substantial effect on children’s long-term school career by increasing the likelihood of enrolling in an advanced secondary school track three years later. Thus, self-regulation teaching can be integrated into the regular school curriculum at low cost, is easily scalable, and can substantially improve important abilities and children’s educational career path.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at something else that should also be more widely taught in schools to improve all students’ chances of success in life, something that has come to be called the “Success Sequence.”

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6.