Why Different Skin Colors? – Part 2

The cultural evolution of racist concepts based on skin color.

In the last essay we looked at how biological evolution produced different skin colors. In this essay, we’ll look at how ideological evolution (the evolution of ideas) produced racist views based on skin color.

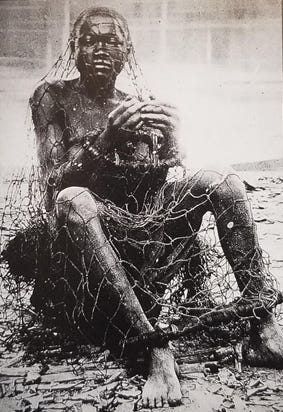

It starts with the horrific slave trade that developed in Africa.

Slavery was widespread in Africa because tropical temperatures bred insects that targeted animals, inhibiting animal domestication for use in transporting goods and cultivating crops. So in Africa, human slaves were used instead. As David S. Landes describes in his book The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor:

In the case of African trypanosomiasis, the vector is the tsetse fly, a nasty little insect that would dry up and die without frequent sucks of mammal blood. Even today, with powerful drugs available, the density of these insects makes large areas of tropical Africa uninhabitable by cattle and hostile to humans. In the past, before the advent of scientific tropical medicine and pharmacology, the entire economy was distorted by this scourge: animal husbandry and transport were impossible; only goods of high value and low volume could be moved, and then only by human porters. Needless to say, volunteers for this work were not forthcoming. The solution was found in slavery, its own kind of habit-forming plague, exposing much of the continent to unending raids and insecurity. All of these factors discouraged intertribal commerce and communication and made urban life, with its dependence on food from outside, just about unviable. The effect was to slow the exchanges that drive cultural and technological development.

As Basil Davidson, in his book The African Slave Trade, explains:

For their part, the [African] coastal chiefs were not slow in understanding where their own commercial interest lay. They in turn endeavored to win a monopoly on the landward side of the [slave] trade … whence most of the captives must come. [The African coastal chiefs] also fought each other as the Europeans did, sought alliance with this or that European nation, stormed their rivals, enslaved them, sold them off; or were themselves seized and sold … In this the manners of Africa were no different from those of Europe … [Europe’s] colonial years [in Africa] were always humiliating, often harsh … But they were relatively few: less than a third of the duration of the major period of the slave trade. They barely spanned three lifetimes … [For Africa,] it was obviously an impoverishment to send away the very men and women who would otherwise produce wealth at home. In exporting slaves, Africans exported their own capital without any possible return in interest or in the enlargement of their economic system … In the face of ever more pervasive demand for slaves, local [African] industries dwindled or collapsed. Where the only produce that was readily marketable was the producer himself (or herself), handicrafts and cottage industries could not thrive, let alone expand.

So entrenched was the slave trade in the African economy, as Davidson reminds, African rulers implored Britain not to abolish the slave trade: “Astonished at Britain’s sudden opposition to a trade she had done so much to call into being and extend, African chiefs and rulers at first tried to dissuade their partner from this momentous step.”

And slavery also continued, and continues, long after it was abolished in the Americas. As James Walvin writes in his book A Short History of Slavery:

By 1888, slavery had been swept away across the Americas. The same could not be said for Africa, however. Indeed, at the very point when Americans shed their appetite for black slaves, there may have been more slaves in Africa than ever before, more even than had been shipped across the Atlantic in the entire history of Atlantic slavery.

Despite some modern obsessions with race, many people remain unaware of this history, and its significance. For example, Henry Louis Gates Jr., the chair of Harvard’s Department of African and African American Studies, has asked the founder of the “1619 Project” to acknowledge this history and to directly address the role played by African warlords who kidnapped blacks for the slave trade. “Talk about the African world and the slave trade,” Gates urged Nikole Hanna-Jones (at the 1:42:00 minute mark), “This is something black people don't want to talk about. But … 90 percent of the Africans who ended up here were the victims of imperial wars – wars between imperial states in Africa – when Africans were capturing Africans and selling them to Europeans along the coast. There has got to be full disclosure. And we’ve got to talk about that.”

As described in Paul E. Lovejoy’s book Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa (Third Edition), between 1400 and into the Twentieth Century, Islamic powers came to control large portions of Africa that bordered the Muslim Ottoman Empire. Islam itself was founded by a slave-owner, and subsequent interpretations of Islam by Muslim elites were used to justify the enslavement of infidels (non-believers in Islam), which then produced the large majority of slaves in Africa, which in turn became the source of slaves for the transatlantic slave trade to America and the Middle East. As Lovejoy writes:

By the eighth, ninth, and tenth centuries, the Islamic world had become the heir to this long tradition of slavery, continuing the pattern of incorporating black slaves from Africa into the societies north of the Sahara and along the shores of the Indian Ocean. The Muslim states of this period interpreted the ancient tradition of slavery in accordance with their new religion, but many uses for slaves were the same as before – slaves were used in the military, administration, and domestic service … Enslavement was justified on the basis of religion, and those who were not Muslims were legally enslaveable … [For example, noted Islamic scholar] Ahmad Baba’s legal interpretation was based on earlier scholarly opinions; hence [his] book also chronicles attitudes toward slavery over many centuries: “[T]he reason for slavery is non-belief and the … non-believers are like other kafir whether they are Christians, Jews, Persians, Berbers, or any others who stick to non-belief and do not embrace Islam … This means that there is no difference between all the kafir in this respect. Whoever is captured in a condition of non-belief, it is legal to own him, whosoever he may be, but not he who was converted to Islam voluntarily, from the start …”

The demand for slaves in Muslim territories in the Middle East was so great it was the major source of profits in trading between Europe and the Middle East throughout the Early and High Middle Ages, and Muslim powers enslaved blacks and whites alike. Indeed, as the BBC reports, “The term slave has its origins in the word slav. The slavs, who inhabited a large part of Eastern Europe, were taken as slaves by the Muslims of Spain during the ninth century AD.” And according to Robert C. Davis in his book Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800:

between 1530 and 1780 there were almost certainly a million and quite possibly as many as a million and a quarter white, European Christians enslaved by the Muslims of the Barbary Coast … In fact, even a tentative slave count in Barbary inevitably begs a host of new questions. To begin with, the estimates arrived at here make it clear that for most of the first two centuries of the modern era, nearly as many Europeans were taken forcibly to Barbary and worked or sold as slaves as were West Africans hauled off to labor on plantations in the Americas.

In 1801, when the Muslim Ottoman provinces of Northern Africa authorized ships to capture and enslave Americans at sea, President Jefferson sent the Marines to stop them.

Starting in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the slave trade came to be dominated by Muslim African slave ports. And it’s from the Muslim slave trade in Africa that racist views based on skin color began to emerge.

As described by historian James Walvin in A Short History of Slavery, “The Islamic tradition of enslavement … meant that, in the very years when slavery was in sharp decline elsewhere in Europe, slavery was confirmed as an unquestioned feature of Iberian life [Iberia constitutes the land between Spain and Portugal],” which ultimately made its way to the Caribbean and South America through the discoveries of Christopher Columbus on behalf of Spain. Walvin continues, “In time, it came to be assumed that black Africans were natural slaves, though this had not been the case initially ... Arabs/Muslims began to think of black Africans as ideally suited for slavery. Gradually, a distinct racial prejudice emerged.”

As James Sweet has chronicled in “The Iberian Roots of American Racist Thought,” the racism that came to characterize American slavery derives from the cultural and religious history of Islamic slave practices, as Islamic attitudes about blacks and slavery spread to Spain, Europe generally, and then America. As Sweet writes:

The racist ideologies of fifteenth-century Iberia grew out of the development of African slavery in the Islamic world as far back as the eighth century. From 711 until their expulsion in 1492, Muslims controlled a significant portion of the Iberian peninsula. At its height, the Muslim world extended east to China. Wide-ranging Islamic influence had profound effects on the thinking of Iberians and, in many respects, charted the course of emerging racial hierarchies. By the ninth century, Muslims were making distinctions between black and white slaves. These invidious distinctions are best reflected in the two Arabic words for slave. The word ‘abd (plural ‘abid), the traditional word for slave, embodied its legal meaning, but in the popular dialect, European slaves came to be called mamluks. The white mamluk commanded a higher price than the black ‘abd because he could bring a substantial Christian ransom or be exchanged for a Muslim captive. The differing treatment of white and black slaves reflected their relative worth. The mamluk was viewed as an investment to protect, whereas the ‘abd’s value was based on his labor as an expendable means of production … This early distinction, which identified blacks as subordinate Others, was not limited to slaves. Free blacks were also known as ‘abid. For the emancipated slave, ‘abd no longer carried its legal stigma, but the color distinction was no less pernicious. Opportunities for free blacks were limited to such lowly occupations as butchers and bath attendants. Thus even in freedom the black African performed the tasks of a social and ethnic inferior … As reflected in Arabic linguistic constructions, religious assumptions, and literary records [,] blacks, regardless of their legal status, were always viewed as morally and culturally inferior. The Muslim world expected blacks to be slaves.

Muslim religious scholars used the story of Canaan’s children in the Bible to justify black slavery. As Sweet continues:

Despite the absence of any characterization of Canaan’s children according to color, race, or ethnicity in the biblical version … [a] tenth-century Persian historian, Tabari, presented a typically racial response. In what is considered the major Arabic historical work of the period, Tabari wrote:

“Ham begot all blacks and people with crinkly hair. Yafit [Japheth] all who have broad faces and small eyes (that is, the Turkic peoples) and Sam [also called ‘Shem’ or ‘Sem,’ the mythical ancestor of the ‘Semites’] all who have beautiful faces and beautiful hair (that is, the Arabs and Persians); Noah put a curse on Ham, according to which the hair of his descendants would not extend over their ears and they would be enslaved wherever they were encountered.”

In Muslim cosmology, the sub-Saharan African emerged as the son of Ham, destined to perpetual servitude. The Hamitic curse provided a justification for the increasing debasement of sub-Saharan Africans. Muslim vilification of blacks was constantly being refined as blackness and slavery came to be regarded as synonymous. Muslims came to view slavery as the condition that best suited sub-Saharan Africans. It had been an integral part of Islamic society since the religion’s beginnings. Even the Prophet Mohammed was a slaveholder, and Muslim teaching associated slavery with nonbelief, making the heathen condition an excuse for enslavement. The black pagans of sub-Saharan Africa were the most vulnerable to Muslim conquest and enslavement for several reasons. First, Islamic law prohibited the enslavement of freeborn Muslims. Moreover, no Christian or Jew living under the protection of an Islamic government could be legally enslaved. Sources of servile labor had to be found outside of those countries living peacefully under Islamic rule. Until the late Middle Ages, captives were taken from north of the Mediterranean and south of the Sahara. When European political stability and military organization began to provide a formidable threat to Muslim dominance, after the eleventh century, the ethnically fragmented nations of Africa were a more inviting target for human exploitation. Blackness quickly became a metaphor for servitude, and the curse of Ham legitimized the continued subjugation of black Africans. Over time, Iberian Christians became acquainted with the Muslim system of black slavery and adopted the same sets of symbols and myths, with additional arguments. Not only were blacks not Christians, but they were the Muslims’ servants, the heathen’s heathen, doubly cursed by their status as nonbelievers and by their servile condition. The blackness of the sub-Saharan Africans contrasted more sharply with white Iberians than it did with tawny-colored Muslims, who constituted the majority of the Muslim population in Iberia and North Africa. The invidious perception of difference, expressed in language that suggested black inferiority, became refined and sharpened by Muslims, Jews, and Christians of Iberian origin.

These views predated, and subsequently informed, the racist views of prominent Western European commentators to follow. As Sweet continues:

[T]he similarities in the evolution of slavery and the perceptions of black Africans in Muslim Spain and Christian Spain were great indeed … Representatives of the church not only invoked the Hamitic curse when attempting to justify African slavery, but they also recognized that their Muslim enemies treated blacks as inferior Others. Therefore, blacks were viewed as inferior to the Muslim infidel and were accorded very few Christian rights by the Catholic Church … By the fifteenth century, many Iberian Christians had internalized the racist attitudes of the Muslims and were applying them to the increasing flow of African slaves to their part of the world … By the time of the Columbian encounter [Columbus’ voyage to the New World], race had evolved into an independent and deeply etched element of the Iberian consciousness, not simply a manifestation of more fundamental social and cultural relationships. Race, and especially skin color, defined the contours of power relationships. As a result of centuries of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish inscription in the social order, racial stratification attained its own independent logic, deeply woven into the social and cultural fabric of fifteenth-century Iberia. The legacy of Iberian racism would endure in the Americas. Iberian racism was a necessary precondition for the system of human bondage that would develop in the Americas during the sixteenth century and beyond … The virulence of racism increased as economic imperatives fueled Africans’ debasement, but the origins of racism preceded the emergence of capitalism by centuries. Biological assumptions that were familiar to a nineteenth-century Cuban slaveowner would have been recognizable to his fifteenth-century Spanish counterpart. The rhetoric of debasement knew no national or chronological boundaries. The racist attitudes that existed in tenth-century Andalusia are in many respects prominent in the American mind today, a stark expression of their longevity, a continuing reminder of the civilized West’s failures, and a stain on its conscience.

As Bernard Lewis has further described in his book Race and Slavery in the Middle East, “Inevitably, the large-scale importation of African slaves influenced Arab (and therefore Muslim) attitudes to the peoples of darker skin whom most Arabs and Muslims encountered only in this way,” and as historian David Brion Davis explains in his book Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World, “The Arabs and other Muslim converts were the first people to make use of literally millions of blacks from sub-Saharan Africa and to begin associating black Africans with the lowliest forms of bondage … racial stereotypes were transmitted, along with black slavery itself.”

Racist views have roots that are long and deep, extending from the place whence all humanity originated, and racist ideologies will likely continue to pop up here and there like stubborn weeds, with new, mutated versions of the sorting of people based on race appearing. (President Biden’s head of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, Kristen Clarke, while in college at Harvard, wrote in the Harvard newspaper that “Melanin endows Blacks with greater mental, physical and spiritual abilities.”)

But if more people come to understand both the true origins of different skin colors, and the roots of false racist ideologies, we can hope skin color will become more a scientific teaching moment on evolution, and less an endless excuse for treating people differently.