In 2018, majorities of students polled said they supported both free speech and “inclusion and diversity.” When asked which was more important, 53 percent said inclusion and diversity and only 46 percent said free speech. Among men, 61 percent favored free speech. But only 35 percent of women did so.

As Michael Barone has written, “That number is of particular concern, because women are now a majority of college and university students. They appear to be a preponderance of the campus administrators who enforce schools’ speech and sexual assault codes, at a time when administrators outnumber teachers in higher education.”

In 2016, among college freshmen, there was the largest gender gap in self-reported liberalism to date (a 12.2 percentage point difference between the number of women reporting being “liberal or far left” compared to men).

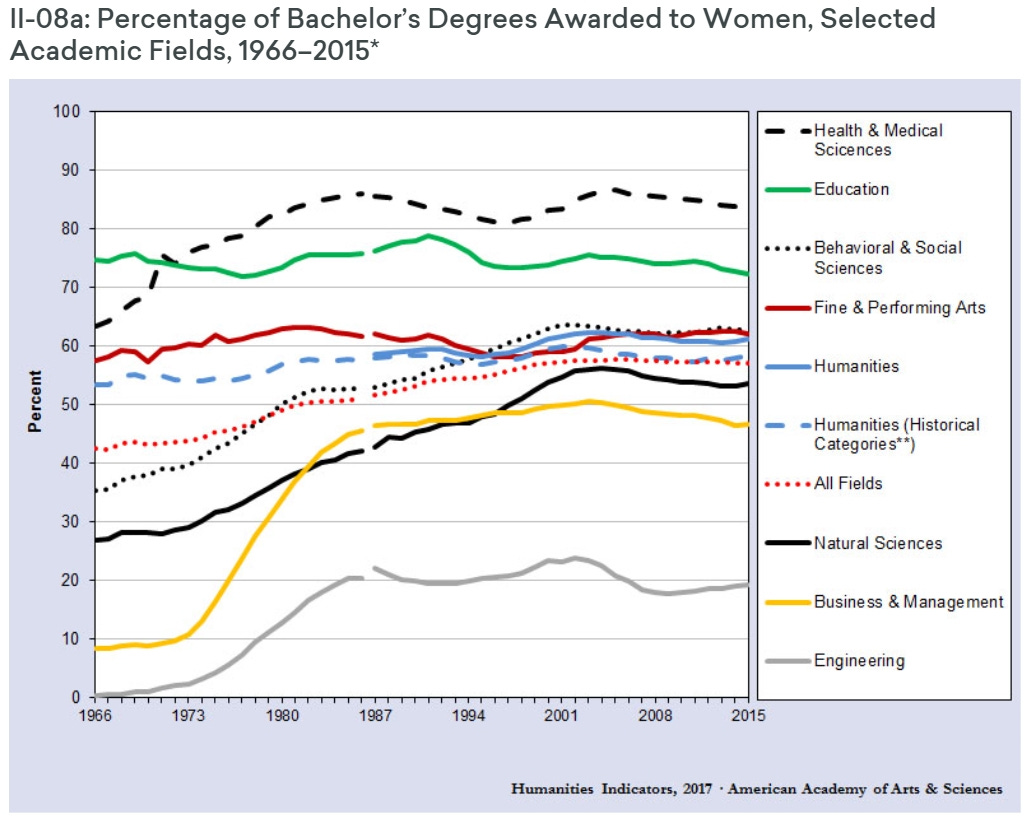

Women also overwhelmingly constitute majors in “Ethnic, Gender, and Cultural Studies,” in that almost 80% of bachelor’s degrees in such studies are awarded to women.

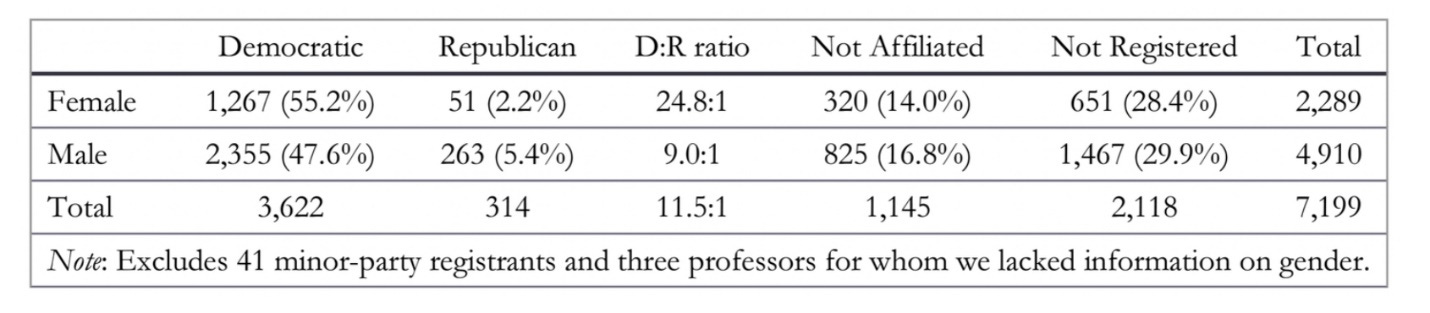

And among academics, “while 10% of male academics are Republicans, less than 4% of female academics are.”

Eric Kaufmann in his report for the Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology compiled data from several different surveys of graduate students and academics and found that women were more likely to support dismissal campaigns, more likely to discriminate against conservatives, and more likely to support diversity quotas for reading lists.

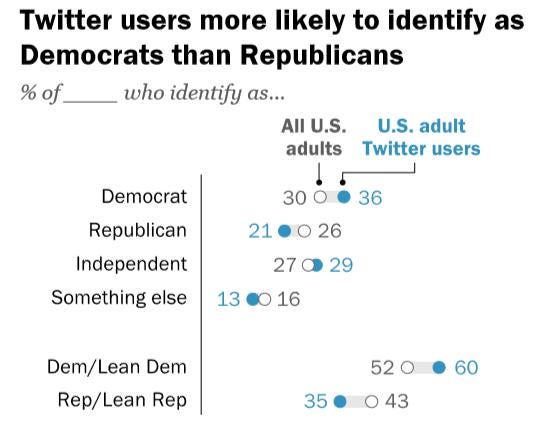

Twitter users are largely Democrat or Democrat-leaning, and the most frequent tweeters are women who tweet about politics.

As Professor Glenn Reynolds summarizes the evidence that the use of social media to transmit information is associated with more harm than good in his book The Social Media Upheaval:

According to a study by computer scientists at Columbia University and the French National Institute, 59 percent of people who share a link on social media don’t read the underlying story … As Caitlin Dewey reported in The Washington Post: “Worse, the study finds that these sort of blind peer-to-peer shares are really important in determining what news gets circulated and what just fades off the public radar. So your thoughtless retweets, and those of your friends, are actually shaping our shared political and cultural agendas.” … Commenting on this study in Forbes, Jayson DeMers writes: “The circulation of headlines in this way leads to an echo chamber effect. Users are more likely to share headlines that adhere to their pre-existing conceptions, rather than challenging them, and as a result, publishers try to post more headlines along those lines. Social groups regurgitate the same types of posts and content over and over again, leading to a kind of information stagnation. This is one of the most powerful negative repercussions of the blind sharing effect. This trend also makes it easier for journalists and content publishers to manipulate their audiences—whether they intend to or not. In a headline, one small word change can make a big difference, and even if you report all the real facts in the body of your article, the way you shape a headline can completely transform how users interpret your presentation of information. This is a dangerous and powerful tool.” … According to a 2017 Pew study, 67 percent of Americans get at least some of their news from social media … In his work The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, Nicholas Carr wrote that prior centuries’ technological change had worked to encourage people to think longer and harder than in the past. The rise of printed books, which could present arguments and marshal facts on a scale previously unknown, actually changed how people thought and argued. “The arguments in books became longer and clearer, as well as more complex and more challenging, as writers strived self-consciously to refine their ideas and their logic … The advances in book technology changed the personal experience of reading and writing. They also had social consequences.” The widespread process of deep, attentive reading, Carr writes, changed people and changed society. “The literary mind,” he writes, “once confined to the cloisters of the monastery and the towers of the university had become the general mind … The words in books didn’t just strengthen people’s ability to think abstractly, they enriched people’s experience of the physical world, the world outside the books.” All that has changed, he writes, in the Internet age, a claim that seems surely to be stronger today than a decade ago. “Dozens of studies by psychologists, neurobiologists, educators and Web designers point to the same conclusion: When we go online, we enter an environment that promotes cursory reading, hurried and distracted thinking, and superficial learning. It’s possible to think deeply while surfing the Net, just as it’s possible to think shallowly while reading a book, but that’s not the type of thinking the technology encourages and rewards.

Researchers found that when people heard a human voice articulate contrary political views, they were less likely to demonize those articulating them, indicating reading posts on social media rather than hearing them verbally articulated by a human being may be exaggerating political polarization. As the researchers wrote:

We predicted that beyond conveying the contents of a person’s mind, a person’s speech also conveys mental capacity, such that hearing a person explain his or her beliefs makes the person seem more mentally capable -- and therefore seem to possess more uniquely human mental traits -- than reading the same content. We expected this effect to emerge when people are perceived as relatively mindless, such as when they disagree with the evaluator’s own beliefs. Three experiments involving polarizing attitudinal issues and political opinions supported these hypotheses. A fourth experiment identified paralinguistic cues in the human voice that convey basic mental capacities. These results suggest that the medium through which people communicate may systematically influence the impressions they form of each other. The tendency to denigrate the minds of the opposition may be tempered by giving them, quite literally, a voice.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at gender imbalances in higher education.