The Protestant Work Ethic – Part 2

How American today (although perhaps not tomorrow) uniquely exhibits the Protestant work ethic.

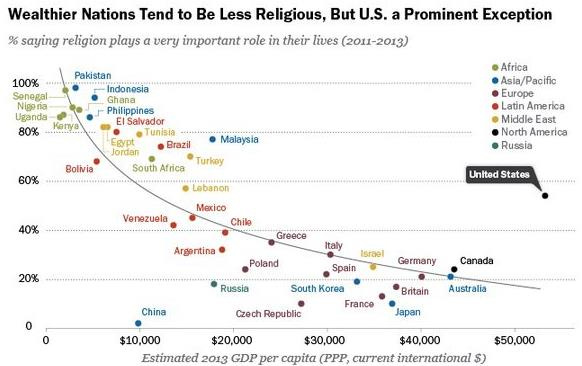

Today, the United States is an international outlier in that it remains a very religious country, while also being the wealthiest.

The concept of individualism and the importance of self-improvement was inculcated in American culture through the so-called “Protestant work ethic.” Economist Robert Barro and Rachel McCleary explain, in their book The Wealth of Religions: The Political Economy of Believing and Belonging, how the Protestant religion came to promote work and economic growth:

Martin Luther, the leader of the Protestant Reformation starting in 1517, stressed that a sinner was saved by faith alone, not by works. “Good works,” in Luther’s theology, consisted of performing one’s work through faith. Daily, ordinary work if performed with faith was good: “A good work [is] when a man works at his trade, walks, stands, eats, drinks, sleeps, and does all kinds of works for the nourishment of his body and for the common welfare, and … God is well pleased with them” (Hart 1995, p. 36). Luther’s understanding was that daily activities performed with the proper attitude and motivation were good works. Luther’s contemporary, John Calvin, held a similar view to Luther’s, that ordinary, daily activities were to be performed by faith: “God sets more value on the pious management of a household, when the head of it, discarding all avarice, ambition, and other lusts of the flesh, makes it his purpose to serve God in some particular vocation” (Calvin [1541] 1845, 4, XIII, p. 16) … Should we choose not to work, we become indolent, giving into bodily urges and physical pleasures, becoming restless, mentally unfocused, and lacking in discipline, and thereby engaging in “folly and rashness.” Although Luther and Calvin agreed with this view, their theologies diverged on the practical implications of work. Whereas Luther viewed work (one’s calling) as maintaining political stability and socioeconomic order, Calvin argued that work gave each person “stability and order” (Ernst Troeltsch [1931] 1992, pp. 641– 650). Thus, in contrast to Luther, mobility and the pursuit of a better position were acceptable in Calvin’s thinking, if done for the right reasons. The idea of improving the quality of one’s circumstances through work, including changing professions if necessary, was part of God’s calling and the godly society. Consistent with this reasoning, Calvin was instrumental in introducing the textile industry in Geneva to employ the poor and idle (p. 642). Economic prosperity and moral rectitude were intertwined with profits from that labor as blessings from God … Calvin argued that God demands of each person a lifetime of good works that are performed according to a morality derived from revealed theology. Only by living a morally good life in this world could one relieve the psychological uncertainty called “salvation anxiety,” never knowing whether one will be saved. Contrary to the Catholic ascetic view that allowed for the continual cycle of “sin, repentance, atonement, release, and sin again,” Calvinist Protestantism required faith and daily moral conduct as the means of assuaging salvation anxiety … Salvation anxiety explains the convergence of religiously driven motivation and economic productivity. A person can never have epistemological certainty that he is saved but can gain confidence and counteract “feelings of religious anxiety” through achievements in this world (Weber [1904– 1905] 1930, p. 67). Only through the daily exercise of self- discipline and methodical hard labor could an individual find some psychological peace … Salvation anxiety motivates people to be productive, but more importantly, to be successful in their labors. Weber also cites the ideas of John Wesley, the founder of Methodism in England in the mid- 1700s. Wesley (1978, pp. 124– 136) famously urged his congregants in 1760 to “gain all you can, save all you can, give all you can.” Thus, his first two precepts support the pursuit of material success in this life.

Protestantism and its teachings have had far-reaching effects. Samuel P. Huntington, in his book Who Are We? The Challenges to America’s National Identity, wrote (as of 2005) of how America today stands out internationally for carrying on that “work ethic” culture:

Their Protestant culture has made Americans the most individualistic people in the world. In Geert Hofstede's comparative analysis of 116,000 employees of IBM in 39 countries, the mean individualism index was 51. Americans, however, were far above that mean, ranking first with an index of 91, followed by Australia, Britain, Canada, the Netherlands, and New Zealand. Eight of the ten countries with the highest individualism indices were Protestant. A survey of cadets in military academies in 14 countries produced comparable results, with those from the United States, Canada, and Denmark ranking highest in individualism. The 1995-97 World Values Survey asked people in 48 countries whether individuals or the state should be primarily responsible for their welfare. Americans (with Swedes) came in close seconds to Swiss in emphasizing individual responsibility. In a survey of 15,000 managers in several countries, the Americans scored the highest on individualism, Japanese the lowest, with Canadians, British, Germans, and French between them in that order. The authors of the study concluded: “American managers are by far the strongest individualists in our national samples. They are also more inner-directed. Americans believe you should 'make up your mind' and 'do your own thing' rather than allow yourself to be influenced too much by other people and the external flow of events.”

As Huntington described the essence of the “Protestant work ethic”:

The work ethic is a central feature of the Protestant culture, and from the beginning America’s religion has been the religion of work. In other societies, heredity, class, social status, ethnicity, and family are the principal sources of status and legitimacy. In America, work is. In different ways both aristocratic and socialist societies tend to demean and discourage work. Bourgeois societies promote work. America, the quintessential bourgeois society, glorifies work. When asked “What do you do?” almost no American dares answer “Nothing.” As Judith Shklas has pointed out, throughout American history social standing has depended on working and earning money by working. Employment is the source of self-assurance and independence. “Be industrious and FREE,” as Benjamin Franklin put it … “The addiction to work,” [Judith] Shklar comments, “that this [attitude] induced was noted by every visitor to the United States in the first half of the nineteeth century.” In the America of the 1830s, the Swiss-German Philip Schaff observed, prayer and work were linked together and idleness was sinful. The Frenchman Michel Chevalier, who also visited America in the 1830s, commented “The manners and customs are those of a working, busy society. A man who has no profession and – which is nearly the same thing – who is not married enjoys little consideration; he who is an active and useful member of soeicty, who contributed his share to augment the national wealth and increase the numbers of the population, he only is looked upon with respect and favor. The American is brought up with the idea that he will have some particular occupation and that if he is active and intelligent he will make his fortune. He has no conception of living without a profession, even when his family is rich. The habits of life are those of an exclusively working people.”

So ingrained was this work ethic, that it became a central argument against the institution of slavery in the 1800’s:

The right to labor and to the rewards of labor was part of the 19th-century arguments against slavery, and the central right espoused by the new Republican Party was the “right to labor productively, to pursue one’s vocation and reap its rewards.”

In popular culture, the work ethic was embodied in the “self-made man” (a term first used by Congressman Henry Clay in a Senate debate in 1832):

The concept of the “self-made man” is a distinctive product of the American environment and culture. In the 1990s Americans remained people of work. They worked longer hours and took shorter vacations than people in other industrialized democracies. The hours of work in other industrialized societies were decreasing. In America, if anything, they were increasing. Among industrialized countries the average hours a worker worked in 1997 were: America-1,966, Japan-1,889, Australia-1,867, New Zealand-1,838, Britain-1,731, France-1,656, Sweden —1,582, Germany-1,560, Norway-1,399. On average, Americans worked 350 more hours per year than Europeans. In 1999, 60 percent of American teenagers worked, three times the average of other industrialized countries … Americans have not only worked more than other peoples, but they have found satisfaction in and identified themselves with their work more than others have. In a 1990 International Values Survey of ten countries, 87 percent of Americans reported that they took a great deal of pride in their work, with only the British reporting a comparable number. In most countries, less than 30 percent of workers expressed that view. Americans have consistently believed that hard work is the key to individual success. In the early 1990s, some 80 percent of Americans said that to be an American it is necessary to subscribe to the work ethic. Ninety percent of Americans said they would work harder if necessary for the success of their organization and 67 percent said they would not welcome social change that would lead to less emphasis on hard work. In their attitudes Americans see society as divided between people who are productive and people who are not. This work ethic has, of course, shaped American policies on employment and welfare. Dependence on what are often referred to as “government handouts” carries a stigma unmatched in other industrialized democracies. In the late 1990s, unemployment benefits were paid for five years in Britain and Germany, two years in France, one year in Japan, and six months in the United States.

Since Huntington wrote those words in 2005, things have changed. Today, surveys conducted in 2022 showed that many more people were reporting having lowered career ambitions and a lower sense of the importance of work in their lives than the contrary:

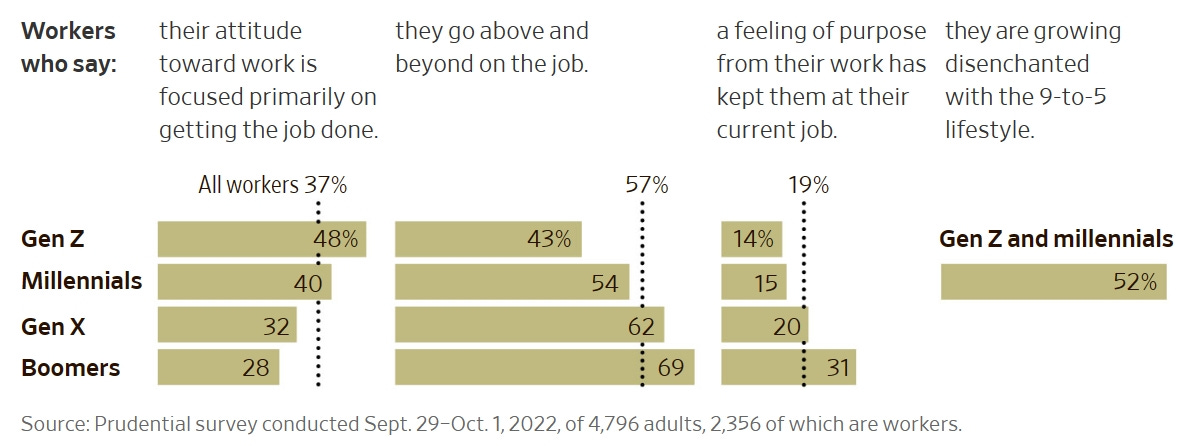

And other surveys showed the youngest generation are disproportionately focused on just “getting the job done” rather than going “above and beyond on the job”:

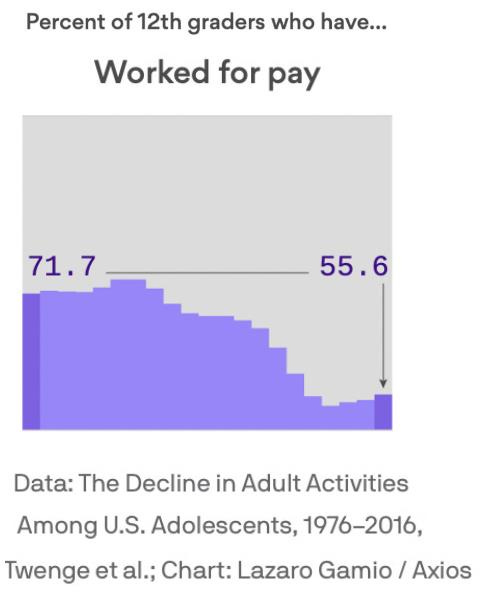

And another study of changes in young people’s behavior found that while 72 percent of 12th graders had worked for pay in the late 1970’s, only 56 percent had done so in 2016.

This concludes our series of essays on the Protestant work ethic.

This discussion was a fascinating insight to me. I have lived in many countries around the world and was always the hardest working soul in all of them. When giving the work/life balance speech in medical school these days, I am the only one left saying "Medicine is a calling: your work is your life. Other things you work in around the edges -- there are plenty of them so do not cry me crocodile tears." But these days residents walk out in the middle of a procedure if their shift is up. If the patient dies...oh well...someone else's problem. The loss of this work ethic will likely be the end of American hegemony and perhaps the end of America -- certainly the end of America as we know it. Who knew I could trace it all to those Puritans with feathers to tickle the sleepers...?