Researchers have found that religious liberty often precedes economic liberty, as follows:

This paper studies the relationship between religious liberty and economic freedom. First, three new facts emerge: (a) religious liberty has increased since 1960, but has slipped substantially over the past decade; (b) the countries that experienced the largest declines in religious liberty tend to have greater economic freedom, especially property rights; (c) changes in religious liberty are associated with changes in the allocation of time to religious activities. Second, using a combination of vector autoregressions and dynamic panel methods, improvements in religious liberty tend to precede economic freedom. Finally, increases in religious liberty have a wide array of spillovers that are important determinants of economic freedom and explain the direction of causality. Countries cannot have long-run economic prosperity and freedom without actively allowing for and promoting religious liberty … While there is a large literature on the importance of institutions for economic growth and development, there has been almost no discussion of the role of religious liberty … Since it is now clear that religious liberty matters, how does it relate with economic freedom? Theoretically, religious liberty could be a prerequisite for at least two reasons. First, the freedom to choose what to believe is a prerequisite for assigning meaning to our actions. Second, religious liberty provides a foundation for other freedoms to emerge, such as property and contracting rights … [T]his paper investigates whether increases in economic freedom precede religious liberty, or whether it is the other way around. The results suggest that religious liberty is not only a much stronger predictor of economic freedom than the other way around, but also that lagged increases in economic freedom do not show up as increases in religious freedom, but they do the other way around.

In a previous essay series, we examined historian Larry Siedentop’s book Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism. While describing the vast cultural impact monasticism had on Western European society early on, he writes:

The way of life associated with the monks also had another important, if unintended, consequence. It rehabilitated “work”– separating work from its association with a servile status, from the stain of ancient slavery. Work acquired a new dignity, becoming even a requirement of self-respect. Basil of Caesarea urged that “we must not use the ideal of piety as an excuse for idleness or a means of escaping toil.” After all, idleness opened the door to “demons,” to images, fancies and appetites, which undermined the construction of a morally upright will. And it was to such a will that the monks sought to subordinate themselves. Personal salvation was understood as a laborious, lifetime quest. It was not a matter of momentary ecstasy or sudden initiation … Gradually work was assimilated to prayer. It became almost a form of prayer. St Basil of Caesarea (c. 330–c. 378), who gave Eastern monasticism its Rule, did not see any conflict between the two. For “it is God’s will that we should nourish the hungry, give the thirsty to drink, and clothe the naked.” Such a reconciliation of the claims of conscience with an emphasis on social obligations was to shape the future of monasticism, Western as well as Eastern.

Joseph Henriech, in his book The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous, describes how the work culture of monks spread throughout neighboring communities, and then throughout Western Europe:

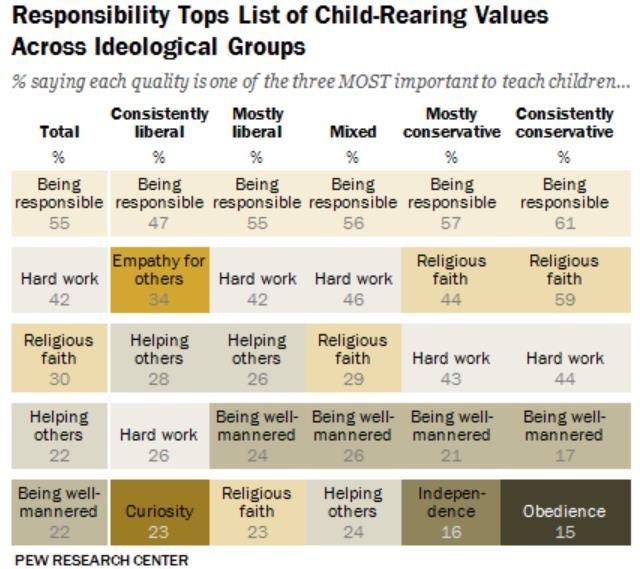

Accompanying the spread of clock-time psychology in Europe [following the introduction of public clocks that helped businesses keep time], an expanding middle class began working longer and harder. This Industrious Revolution, as the economic historian Jan de Vries calls it, can be tracked back to at least 1650 or so, beyond which the trail of direct evidence peters out. I suspect that this rising industriousness was part of a longer-term trend. People’s time psychology was slowly coevolving with a stronger work ethic and greater self-regulation from at least the late Middle Ages through the Industrial Revolution. Clues to these psychological changes can be seen in the spread of mechanical clocks, greater use of the sandglass, rising concerns about punctuality, and the success of the Cistercian Order, with its spiritual emphasis on manual labor, hard work, and self-discipline. And, of course, these concerns and commitments lie at the heart of many Protestant faiths. Ben Franklin was, for example, the son of pious Puritans who lived among Quakers … One key question is: What motivated people to work longer? … Recall that, in addition to their emphasis on self-discipline, self-denial, and hard work, the Cistercians sought out the simplicity and serenity of remote rural areas. The monks accepted non-literate peasants into their order as lay brothers, and these men took vows of chastity and obedience. The monks also employed a range of servants, laborers, and skilled workers. Small communities, often with shops and artisans, sometimes clustered around the outskirts of monasteries. Together, these members, employees, and other contacts threaded social and economic connections that stretched out into the surrounding communities to create communication lines for the transmission of Cistercian values, habits, practices, and know-how. Figure 11.2 [below] shows the distribution of Cistercian monasteries during the Middle Ages. Ninety percent had been founded by 1300. To assess whether the Cistercian presence influenced people’s work ethic after 1300, we can use contemporary survey data (2008–2010) from over 30,000 people spread around 242 European regions. The survey asked whether “hard work” is an important trait for children to learn. To link this survey measure to the Cistercians, Thomas Anderson, Jeanet Bentzen, and their colleagues calculated the density of Cistercian houses per square kilometer for each region outlined in Figure 11.2. Then, they connected everyone in the survey to the region where they grew up. The results show that the higher the density of Cistercian monasteries in a region during the Middle Ages, the more likely a person from that region today is to say that “hard work” is important for children to learn. This only compares people living within the same modern countries and holds after statistically accounting for various regional and individual differences, including people’s education and marital status. The psychological emphasis on “hard work” also manifests in contemporary economic data: regions that experienced a greater Cistercian presence during the Middle Ages are economically more productive in the 21st century and show lower rates of unemployment. Interestingly, the effect of a historical Cistercian presence in a region operates most strongly on Catholics compared to Protestants. That is, Catholics who grew up in regions that had been historically thick with Cistercians are much more likely to endorse the importance of “hard work” for children compared to Catholics from other regions. This makes sense, since the later diffusion of Protestant communities, whose members also often amplified the value of hard work, would have obscured the earlier influences of the Cistercians.

About a thousand years later in America, when asked which qualities are the most important to teach children, those who were “consistently conservative” answered “being responsible” and “hard work” more often than the average American. Those who were “consistently liberal” answered “being responsible” and “hard work” less often than the average American.

When the greater propensity of the more religious in America to get married and have children (as explored in the previous series of essays on Data on Religion and Culture) is added to their prioritizing the encouragement of their children to work hard, the religious may indeed inherit the Earth, or at least America.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how America today (although perhaps not tomorrow) uniquely exhibits the Protestant work ethic.