The Moon Race vs. Race

Hungary’s Numerus Clausus law of 1920, lessons from the Apollo Program, and current attempts to impose education quotas.

Recently, it’s become a trend to exclude Asian Americans from “minority” or “non-white” categories of race or ethnicity because Asian Americans as a group perform well when various outcomes are measured, compared to other people grouped by race, which puts the lie to arguments that America is a country dominated by “white privilege” to the exclusion of opportunities for others. For example, one American university’s list of freshmen admissions and enrollment explicitly lists as a category “Student of Color, minus Asians.”

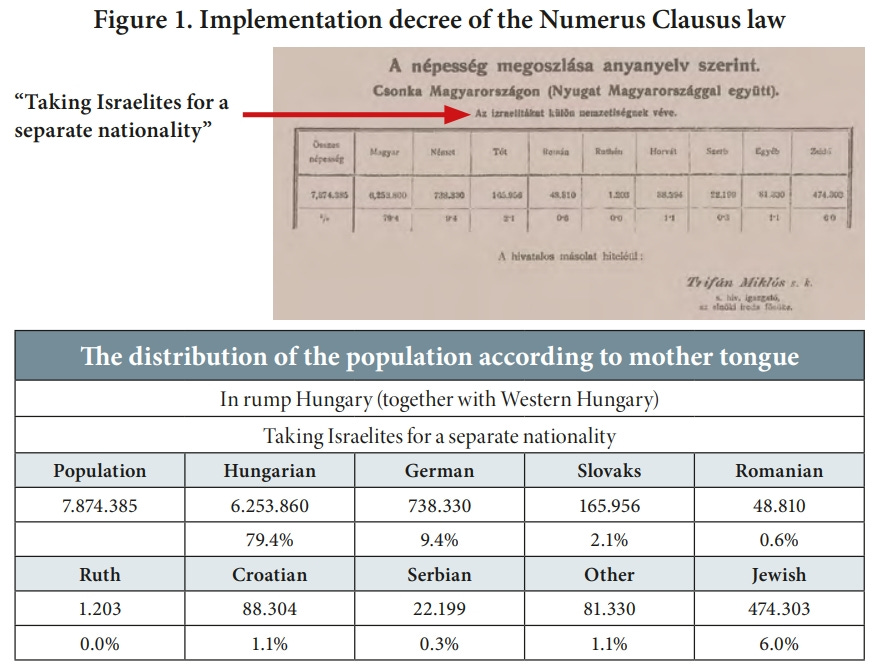

This is starkly politicized recategorization. And this singling out of a politically disfavored group of people based on race brings to mind the first law to target Jewish people for adverse treatment in modern Europe, the Numerus Clausus law. That law also created an arbitrary category for nefarious political purposes. As described by Maria Kovacs in her Simon Wiesenthal Lecture, that law, enacted in Hungary in 1920

listed the proportion of all linguistic nationalities, which was then used to determine the ceiling for admission of students belonging to those nationalities. But the decree created a new, special category for the Jews even though Jews were Hungarian speakers. To make sure that this more than dubious procedure is well understood by the university admission committees, the table contained a sub-heading which pointed out that “Jews are to be taken as a nationality.” So, for the purposes of university admissions, Jews were to be considered members of this newly constructed, so-called “nationality,” irrespective of the language they spoke. With this, the law created a unique rule for Jews, a rule that did not apply to any other Hungarian-speaking citizen of the country. In this way, at least as far as university admissions were concerned, the law effectively withdrew from the Jews their status as equal citizens.

As described by the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies:

Act XXV/1920, the so-called numerus clausus law, which was passed by the Hungarian National Assembly in September 1920, has the dubious merit of being the first antisemitic law of the post-First World War era … The law’s quota of six percent for Jewish students drastically reduced the previous high representation of Jews at university faculties. It also led to the flight of thousands of Hungarian Jewish students (the so-called NC exiles) to universities abroad, robbing the country of many future leading lights of Western academia. Despite the persistent obfuscations and myths surrounding it, historians agree that the law’s breach of the principle of equal citizenship paved the way for the openly discriminatory anti-Jewish laws enacted in Hungary in the late 1930s and, ultimately, the Hungarian Holocaust.

The creation of a new category of “Student of Color, minus Asians” is the same sort of “breach of the principle of equal citizenship” that can pave the way for even more discriminatory laws. It’s time to take this sort of thing as seriously as its past precedents portend.

Already, there are moves to limit participation by Asian students in advanced science and math program because it’s thought “too many” Asians (with demonstrated superior academic performance) are taking the place of others, in a way that results in student bodies that may not reflect the racial composition of society as a whole. But pitting the advancement of knowledge against “social justice” for a politically preferred racial group is not “social justice” at all. It’s a deeply flawed mission that aims for “social justice” at the price of human accomplishment, especially when that accomplishment will help improve the well-being of all people. Rising knowledge, like a rising tide, lifts all boats.

I was moved by that lesson while reading Charles Fishman’s book “One Giant Leap: The Impossible Mission That Flew Us to the Moon,” which describes a little-remembered “civil rights” protests that accompanied the Apollo program. The Apollo space program was the embodiment of humanity’s dedication to expanding knowledge in order to find new routes toward yet more knowledge. But it was not without contemporary controversy.

Fishman writes:

It was a common critique in the 1960s, and it still is today: that somehow, by devoting time, money, and energy to space travel, we must of necessity neglect other things. If we go to space, we can’t have good schools or accessible health care or clean water or a strong spirit of community. It’s like saying art museums cause poverty.

The book cites an article that describes a civil rights protest that occurred at the Kennedy Space Center as the countdown had already begun for the first successful flight to the moon. As Roger D. Launius writes in that Space Policy article entitled “Managing the unmanageable: Apollo, space age management and American social problems”:

At the time of Apollo 11 the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, successor to Martin Luther King as head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, protested against the launch to call attention to the plight of the poor of the USA. He and 500 marchers of the Poor People’s Campaign arrived at the Kennedy Space Center to contest the meaning of the Moon launch. The protesters held an all-night vigil as the countdown proceeded and then made a march with two mule-drawn wagons as a reminder that, while the nation spent significant money on the Apollo program, poverty ravaged many Americans’ lives. As Hosea Williams said at the time, ‘‘We do not oppose the Moon shot. Our purpose is to protest America’s inability to choose human priorities.”

Thomas Paine, the head of NASA at the time, described the event as follows:

We were coatless, standing under a cloudy sky, with distant thunder rumbling, and a very light mist of rain occasionally falling. After a good deal of chanting, oratory and lining up, the group marched slowly toward us, singing ‘‘We Shall Overcome’’. In the lead were several mules being led by the Rev. Abernathy, Hosea Williams and other leading members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The leaders came up to us and halted, facing Julian [Scheer] and myself, while the remainder of the group walked around and surrounded us. One fifth of the population lacks adequate food, clothing, shelter and medical care, [Rev. Abernathy] said. The money for the space program, he stated, should be spent to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, tend the sick, and house the shelterless.

Launius then describes what happened next:

Abernathy said that he had three requests for NASA, that ten families of his group be allowed to view the launch, that NASA “support the movement to combat the nation’s poverty, hunger and other social problems” and that NASA’s technical people work “to tackle the problem of hunger.” Paine responded with one of the best answers ever crafted in such a setting. He invited Abernathy and a busload of his supporters to view the Apollo 11 launch from the VIP site with other dignitaries. Paine commented on how hard it was to apply NASA’s scientific and technological knowledge to the problems of society.

“I stated that if we could solve the problems of poverty in the United States by not pushing the button to launch men to the moon tomorrow then we would not push that button’’. He added: I said that the great technological advances of NASA were child’s play compared to the tremendously difficult human problems with which he and his people were concerned. I said that he should regard the space program, however, as an encouraging demonstration of what the American people could accomplish when they had vision, leadership and adequate resources of competent people and money to overcome obstacles. I said I hoped that he would hitch his wagons to our rocket, using the space program as a spur to the nation to tackle problems boldly in other areas, and using NASA’s space successes as a yardstick by which progress in other areas should be measured. I said that although I could not promise early results, I would certainly do everything in my own personal power to help him in his fight for better conditions for all Americans, and that his request that science and engineering assist in this task was a sound one which, in the long run, would indeed help. Paine then asked Abernathy, when he held a prayer meeting later that day with his protestors, that they “pray for the safety of our astronauts.” As Paine recalled, “He responded with emotion that they would certainly pray for the safety and success of the astronauts, and that as Americans they were as proud of our space achievements as anybody in the country.”

It’s time to return to that spirit of progress, and be equally proud of academic accomplishments regardless of race.

That’s not just a principle, but also a policy that’s helped demonstrate the advantages of systems of government that reward merit and thereby encourage human flourishing. As Fishman writes:

Apollo was not a waste of money. We spent a lot of money, by any measure, but we got our money’s worth. We taught ourselves to fly in space, and that turned out to be just as hard as the people who had to do it thought it would be. The science the astronauts did, the science the astronauts enabled Earthside scientists to do, completely remade our understanding of the formation of the Moon and its composition and geology, and by extension, it changed our understanding of the early years of the Earth and the relationship between the Moon and the Earth. Apollo also accomplished that mission which John F. Kennedy first set for it: it powered America into the leading role in space. It took most of the decade, in fact, but it turned out that democratic capitalism could not be overmatched, even in space … But it was not, in fact, simply two nations racing for the Moon. The Soviets had made it “a test of the system,” as Kennedy put it. Which system had the resources and the skill and the grit to get to the Moon—communism or democracy? The landing of the Eagle on the Moon, the moments when Armstrong and Aldrin stepped off the ladder onto the gray lunar ground—those represented a soaring accomplishment of human ingenuity. The moment when they unfurled the American flag, for all the complexity of America’s role in the world, that underscored that it was also an achievement of human freedom. The American flag meant something very different from the Soviet flag. Instead of the triumph of tyranny, it was just the opposite: going to the Moon is forever the symbol of what freedom can accomplish, of how far human aspiration can take you.

The freedom to pursue knowledge advances human aspiration. Promoting human aspiration encourages achievement. And incentivizing achievement motivates everyone to pursue their own opportunities, which is the measure of how far human aspiration can take us.