The Many Devastating Effects of Slavery – Part 1

How black slavery enriched relatively few Southern whites and helped impoverish all the rest.

Nikole Hannah Jones, creator of the 1619 Project, wrote an article in the New York Times Magazine entitled “What Is Owed,” in which she says her framing of American history demands that certain national policies be enacted, and “At the center of those policies must be reparations.” According to Hannah Jones, “Reparations would go to any person who has documentation that he or she identified as a black person for at least 10 years before the beginning of any reparations process and can trace at least one ancestor back to American slavery,” and “critically, reparations must include individual cash payments to descendants of the enslaved in order to close the wealth gap.” She writes further, “Financial restitution cannot end racism, of course, but it can certainly mitigate racism’s most devastating effects.”

The “wealth gap” refers to existing disparities between aggregate wealth among Americans grouped by race. But slavery, when is was legal in America, itself created a wealth gap that had a disparate impact on free Southern whites, constituting another devastating effect of slavery.

Slavery was an evil institution that had many, many devastating effects beyond the inherent horror of slavery as experienced by slaves themselves. Poor whites in the South suffered, too, at the time, in that their wages plummeted in the face of competition from slaves.

William Julius Wilson, in his book “The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American Institutions, Third Edition,” describes the broader context of American slavery in the South:

Throughout the period of legal servitude, the ownership of slaves was a privilege enjoyed by only a small percentage of free families in the South. Of the 1,156,000 free southern families in 1860, only 385,000 (roughly one-fourth) owned slaves.

And among the large majority of whites who didn’t own slaves was a large majority of those who were the victims of lynching. As Wilson describes:

Lynching, which typified the informal violence of the antebellum South, seldom involved blacks. [Eugene D.] Genovese estimates that less than 10 percent of the more than three hundred lynching victims between 1840 and 1860 were black.

Slavery also had a significant impact on the life prospects of poor whites in that slavery dramatically drove down their wages:

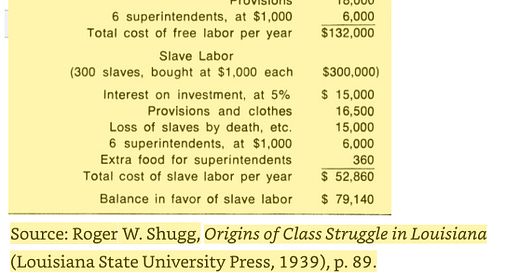

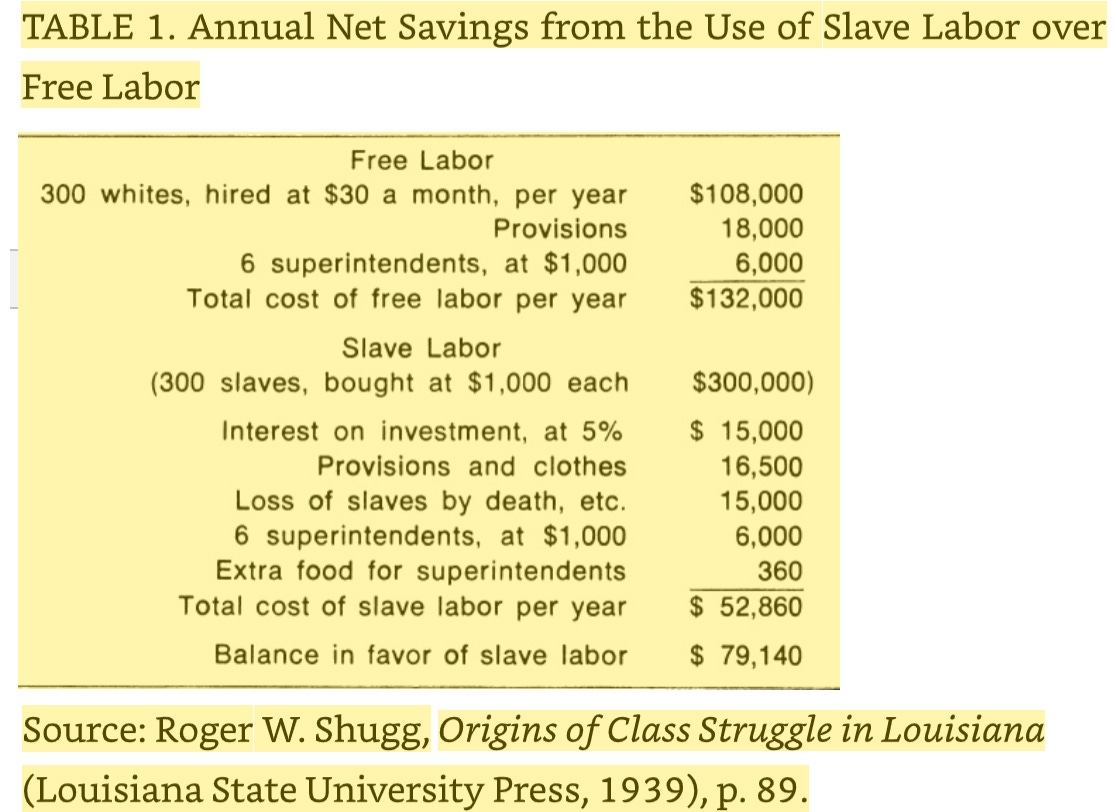

A split labor market along racial lines developed early in the history of the United States as a result of the institutionalization of slavery: split in the sense that slave labor was considered cheaper than free white labor. Aside from the fact that, unlike slaves, white laborers could strike and press for increased wages, thereby narrowing the difference between production cost and profit, the planter and business classes believed that in most situations slave labor was simply a less expensive investment. For example, a Louisiana state senate committee for the construction of canals, levees, and plank roads calculated in 1853 that the state would save $79,140 a year if three hundred slave carpenters and mechanics were used in favor of three hundred white laborers. The figures in Table 1 indicate that if slaves were bought at $1,000 a head, the annual savings on slave labor would actually pay for the original cost in less than four years.

As Bernard Mandel writes in Labor: Free and Slave, “Consequently, in 1853, [the State of] Louisiana abandoned the system of hiring free labor and purchased one hundred slaves … and an equivalent number of workers had to search elsewhere for employment at slave-labor standards.” (At p. 33.)

As Mandel explains:

Since the number of white laborers was generally small outside a few towns, the price of wage labor was determined by the price of slave labor, which was less than the minimum necessary to maintain the workers and his family (for the slave did not have that responsibility). Consequently, the wages of the workmen constantly tended to fall to the level of the price commanded for the hire of slaves, and probably reached that point most of the time … Not only did the laborers have to meet the price of slave labor, but they also had to produce as much as slaves to hold their own in the struggle for existence, and consequently had to deliver a long day’s labor … In the self-sufficient economy of the plantations there was no place for hired labor. The master had to find employment for his slaves throughout the year, for an idle slave was an unprofitable and dangerous one, and there were generally some who were physically incapable of the grueling field tasks. Such men were often trained as skilled craftsmen: carpenters, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, bricklayers. General Marion had called attention to this situation long before when he noted that “the people of Carolina form two classes – the rich and the poor. The poor are generally very poor, because, not being necessary to the rich, who have slaves to do all their work, they get no employment from them.” (At pp. 31-32.)

Mandel quotes a Montgomery, Alabama, mechanic who said the competition with slave labor “like the encroachment of Pharaoh’s plagues, … has extended its conquest throughout the land, and consumes all the sources of the poor man’s living.”

Wilson also emphasizes that slaves didn’t just perform manual labor. As he describes:

Slaves were trained in virtually every branch of skilled and unskilled labor. Those who were not needed on the plantation at a particular time were hired out to firms for construction work and numerous other semiskilled and unskilled jobs. The more frequent the contact between black slaves and white workers in the labor market, the more the wages of white workers were depressed to the level of the price required for the hire of slaves. Bernard Mandel, in his impressive book Labor: Free and Slave, stated that:

“… The ten-hour movement never achieved the dimensions that it did in the North, and had little possibility of success in those circumstances. When the journeymen bricklayers of Louisville were struggling for the ten-hour system, they met an insuperable obstacle in the fact that they were replaceable by slaves, so they had to work as many hours as the slaves or abandon their trade. The stonecutters were able to win the ten-hour day because no slaves were employed in that occupation. But when the carpenters and painters called a strike for shorter hours, it was broken by the employment of slaves on their jobs; some strikers went back to work on the old terms, and others, disgusted and demoralized, emigrated from the state.”

Herman Schluter perceived the effect of slavery on white labor in much the same way by observing that, whereas in 1852 the wages of free laborers in the cotton mills of Tennessee barely amounted to 50 cents a day for males and $1.25 a week for females, in Lowell, Massachusetts, the wages were 80 cents a day and $2.00 a week for men and women cotton-mill workers respectively. And Philip Foner informs us that competition with slave labor reduced wages for southern white workers to the lowest in the nation. “The daily wages in 1860 for day laborers in the North was about $1.11, whereas in most southern states it was between 77 and 90 cents. The daily wage for carpenters in the North for the same year was about $2, while in many states in the South it did not exceed $1.56. While operatives in Georgia cotton factories were earning $7.39 a month, workers in textile mills in Massachusetts doing the same work were getting $14.74.”

Robert William Fogel, the winner of the 1993 Nobel Prize in Economics, in his book Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery, described much the same economic dynamic, in which competition with slaves cut across all manner of occupations:

To a surprising extent, slaves held the top managerial posts. Within the agricultural sector, about 7.0 percent of the men held managerial posts and 11.9 percent were skilled craftsmen (blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, etc.). Another 7.4 percent were engaged in semi-skilled and domestic or quasi-domestic jobs: teamsters, coachmen, gardeners, stewards, and house servants … Laborers accounted for 73 percent of the male slaves in the labor force in 1850, but in 1870 only 49 percent of all males in the labor force were laborers. While slavery clearly limited the opportunities of bondsmen to acquire skills, the fact remains that over 25 percent of of males were managers, professionals, craftsmen, and semiskilled workers. (At pp. 39-40.)

Fogel continues:

The belief that slaves on plantations were mainly occupied in picking or raising cotton is also without foundation in fact. This popular misconception is partly attributable to the widely cited, but badly misinterpreted, statement of the U.S. Census for 1850 that the 2,800,000 slaves in the agricultural sector were distributed among farms producing the great southern staples:

Cotton 73 percent

Tobacco 14 percent

Sugar 6 percent

Rice 5 percent

Hemp 2 percent

Although this distribution of the farm population of slaves is roughly correct, it does not follow that the 2,000,000 slaves on cotton plantations (0.73 * 2,800,000) spent all of their labor time in raising and picking cotton. In the first place, approximately one third of the slaves on cotton plantations were children under ten who were generally exempt from regular labor tasks. Of the remaining 1,400,000 slaves, about 20 percent were (as previously noted) artisans, semiskilled workers, or domestics who were not engaged in field tasks. Moreover, not all of the labor time of the remaining 1,150,000 field hands was spent in producing cotton. Even on farms in which cotton was the primary market crop, most of the labor time of slaves was devoted to other activities than the growing of cotton. (At pp. 41-42.)

Besides being underbid for skilled jobs, when white laborers could get unskilled work it was often of the most dangerous sort. As Mandel explains:

[O]n dangerous jobs, the slaveholder wanted protection from the premature liquidation of his investment. One planter explained the employment of Irishmen on a dangerous job with the remark that “It’s dangerous work, and a negro’s life is too valuable to be risked at it. If a negro dies, it’s a considerable loss, you know.” And in unloading cotton bales, the slaves often worked on deck while the Irishmen stopped the bales as they slid onto the wharf. “The n—s are worth too much to be risked here; if the Paddies are knocked overboard, or get their backs broke, nobody loses anything.”

Regarding per capita income generally, Fogel provides a table (at p. 247) showing that “in both 1840 and 1860 per capita income in the North was higher than in the South. In 1840 the South had an average income which was only 69 percent that of the North’s. In 1860 southern per capita income was still only 73 percent as high as in the North.”

Indeed, as pointed out by historian Timothy Winegard, Abraham Lincoln himself had long recognized that slavery made everyone poorer:

While Lincoln repeatedly assured the slave states that he would not abolish the institution where it already existed, he was also adamant that slavery could not spread west into new states and territories. Poor white farmers, like his own father, needed an opportunity to make a decent living farming food crops on “free soil” detached from the no-win wage competition with unpaid slave labor. The simple economics of slavery impoverished all spectrums of American society, slaves and freemen alike.

Gavin Wright, in an article in the Spring 2022 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, writes that:

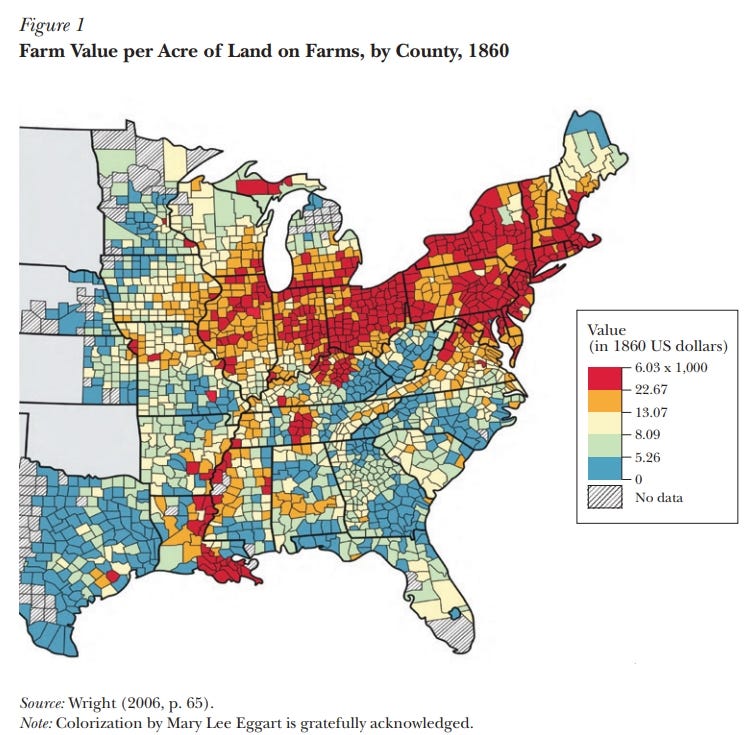

accounts of the sources of US economic growth in the nineteenth-century suggest that slavery and the shift of the slave-owning South to cotton production early in the century had relatively little effect on growth for the nation as a whole. The southern economy shared in the growth acceleration, expanding lands committed to cotton production and raising labor productivity in the process. But the deeper sources of long-run US economic growth were improvements in technology, internal transportation, finance, and education, and the slave-owning South lagged in all of these areas. A simple summary of these patterns might be this: Slavery enriched slaveowners, but impoverished the southern region and did little to boost the US economy as a whole … [T]he spatial pattern of farm value per acre shown in Figure 1 [shows] there is a stark North-South contrast in the value of farmland. More specifically, land values in the free states of the western migration of that time—like Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois—are much higher than the values of the southwestern states—like Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee—except for the most fertile riverine areas.

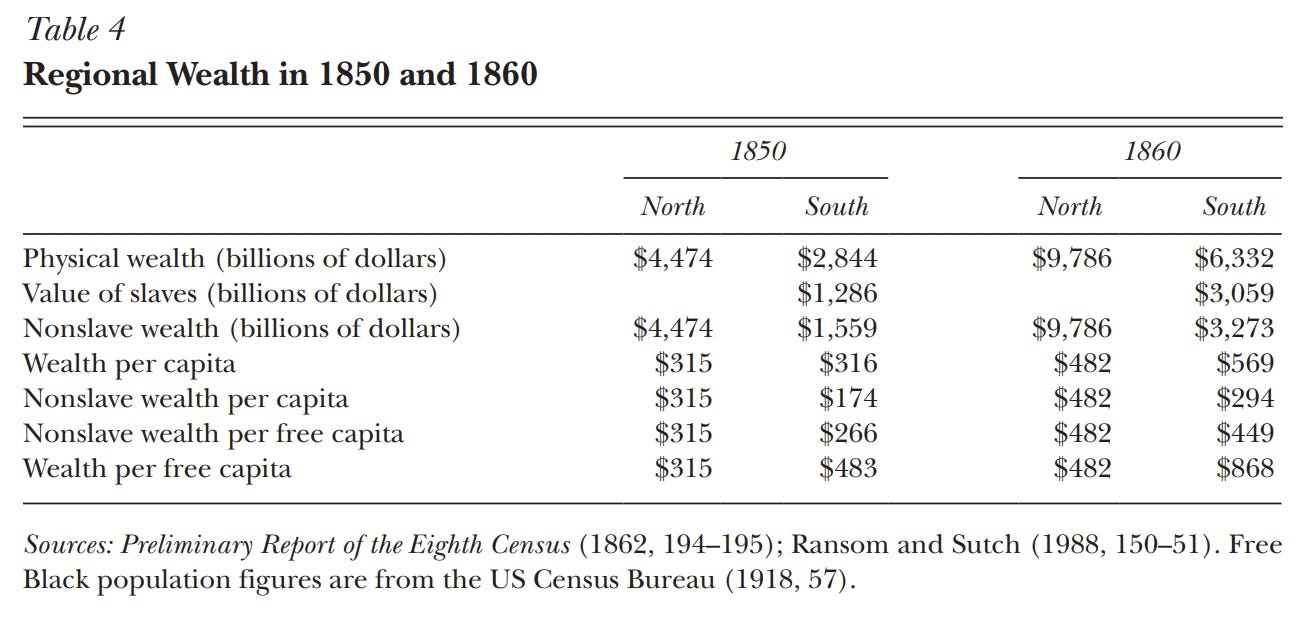

Table 4 reports total and per capita levels of real and personal property from the censuses of 1850 and 1860, building on estimates of slave values constructed by Ransom and Sutch (1988). It is immediately apparent that the question of regional wealth accumulation turns on the treatment of slave values, which accounted for nearly half of all tangible southern wealth in 1860. If slave values are included, the South was the wealthiest region per capita; if only the free population is counted (about two-thirds of the total), the southern advantage was immense, more than 50 percent in 1850, 80 percent in 1860. But if instead we only consider nonhuman wealth, as we would for a modern economy, the North had the advantage, by 80 percent in 1850 and 64 percent in 1860. The northern regional edge prevailed even for the free population alone, though these differences were smaller …

Neither slavery nor cotton were instrumental in the American growth acceleration of the nineteenth century. By contrast, political independence from Great Britain was a critical background factor, by allowing domestic financial institutions and capital markets to emerge, and by liberating state and local entities to sponsor “internal improvements” and other forms of social capital formation. Political independence also allowed the northern US states to abolish slavery, essentially the first abolitions in modern history. Exclusion of slavery under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, in areas where the institution of slavery had many supporters and might well have flourished, was vital for the country’s growth trajectory … The incentives associated with this property, however, led slaveholders to eschew or neglect activities that fostered growth. As owners of scarce, valuable labor, they approved the closing of the African slave trade and discouraged recruitment of free settlers or workers. Because the value of their human property was independent of local development, they did not form local and regional coalitions to promote transportation and towns, as occurred in the free states. For similar reasons, slave-owners saw little benefit to educating the free population of the South and were positively fearful at the prospect of educating slaves. These policies or non-policies were clearly unfavorable for long-run development. The adverse consequences were already visible before the US Civil War. The slave South did not offer attractive, growing markets for farm products, middle-class consumer goods, or new technologies comparable to those emerging from the family farms and cities of the northern states.

The history discussed here is offered to add necessary context to any debates surrounding reparations for slavery. If, as Hannah Jones writes, reparations is necessary to “close the wealth gap” and “mitigate racism’s most devastating effects,” consideration must be given to the diminished wealth slavery imposed on many Southern whites as well, whose suppressed wages on account of slavery gave their own progeny less to work with in the centuries ahead.

(A study on black economic progress after slavery found that any effects of slavery, between 1940 and 2023, were mediated by location, such that by 2023 comparative disparities in black economic progress are explained by the fact that the South during and following the slavery era suffered economically, affecting blacks and whites alike: white Southerners, along with black Southerners, earn less than whites in other parts of the country as well.)

The next essay will explore the dire effects of slavery on the economy of the South as a whole, and on Africa, providing further context regarding slavery’s aggregate negative impact on wealth and progress throughout the world.