Race and the Police – Part 3

Data on police treatment of blacks.

In previous essays we examined the value of police in deterring crime and the black crime rate. In this essay we’ll examine the evidence that informs the answer to the question as to whether police unfairly target blacks for arrest.

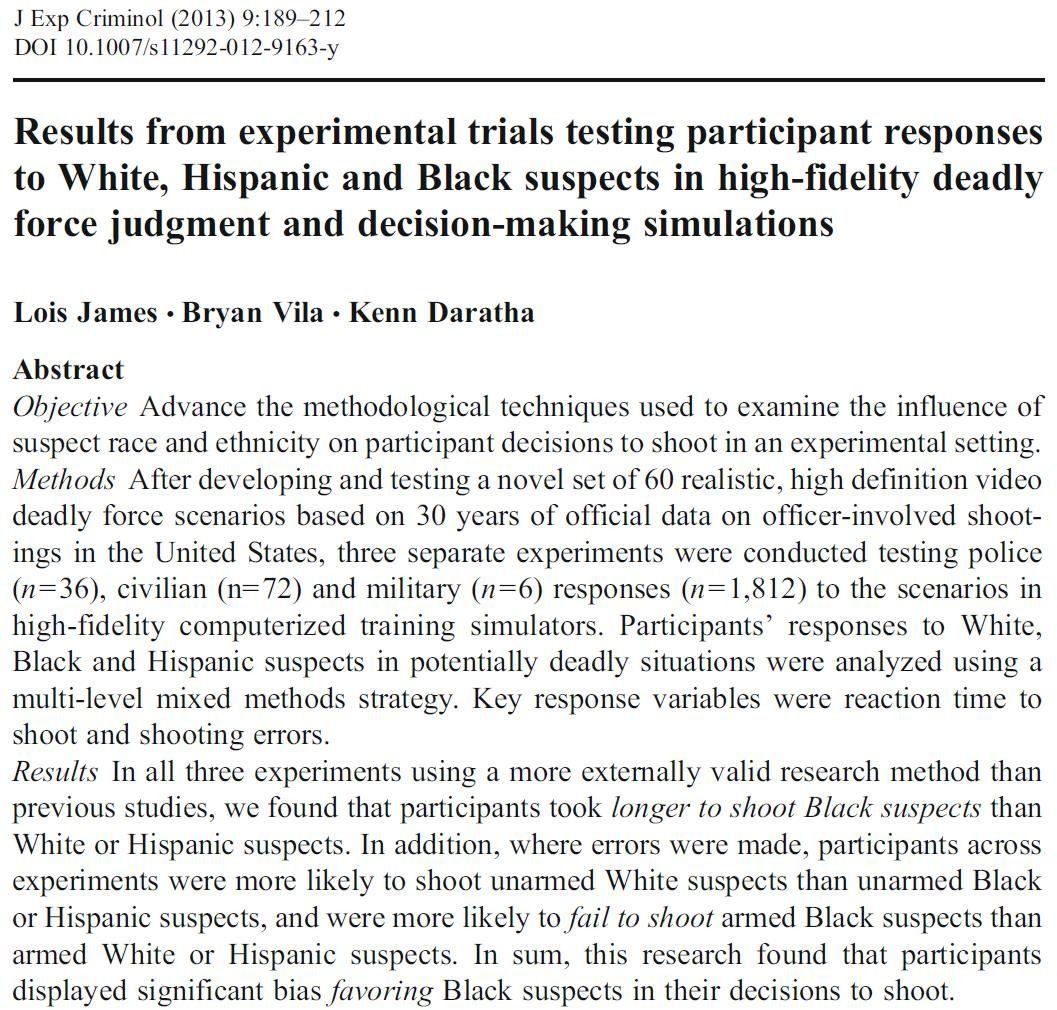

Regarding treatment by police, researchers have shown that police officers tested in simulators took longer to shoot black suspects than white or Hispanic suspects, displaying significant bias favoring black suspects in their decisions to shoot compared to white and Hispanic suspects. Follow-up studies have confirmed these results. Roland G. Fryer, Jr., of Harvard University, found that “On the most extreme use of force – officer-involved shootings – we find no racial differences in either the raw data or when contextual factors are taken into account.”

In one of the first studies to comprehensively examine not only the lethal use of force but also injuries inflicted by police that do not result in death, which are far more common than fatalities, it was found that police are also not any more likely to injure blacks or Hispanics than whites after they are stopped.

A study published in August 2019 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that the more frequently officers encounter violent suspects from any given racial group, the greater the chance that a member of that group will be fatally shot by a police officer and that there is “no significant evidence of antiblack disparity in the likelihood of being fatally shot by police.” That study found:

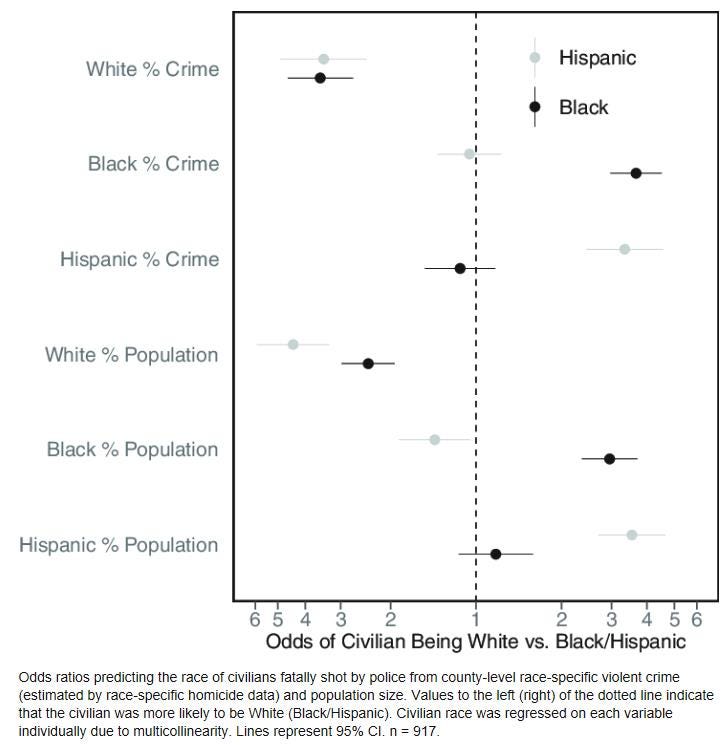

There is widespread concern about racial disparities in fatal officer-involved shootings and that these disparities reflect discrimination by White officers. Existing databases of fatal shootings lack information about officers, and past analytic approaches have made it difficult to assess the contributions of factors like crime. We create a comprehensive database of officers involved in fatal shootings during 2015 and predict victim race from civilian, officer, and county characteristics. We find no evidence of anti-Black or anti-Hispanic disparities across shootings, and White officers are not more likely to shoot minority civilians than non-White officers. Instead, race-specific crime strongly predicts civilian race. This suggests that increasing diversity among officers by itself is unlikely to reduce racial disparity in police shootings. … Despite extensive attention to racial disparities in police shootings, two problems have hindered progress on this issue. First, databases of fatal officer-involved shootings (FOIS) lack details about officers, making it difficult to test whether racial disparities vary by officer characteristics. Second, there are conflicting views on which benchmark should be used to determine racial disparities when the outcome is the rate at which members from racial groups are fatally shot. We address these issues by creating a database of FOIS that includes detailed officer information. We test racial disparities using an approach that sidesteps the benchmark debate by directly predicting the race of civilians fatally shot rather than comparing the rate at which racial groups are shot to some benchmark. We report three main findings: 1) As the proportion of Black or Hispanic officers in a FOIS increases, a person shot is more likely to be Black or Hispanic than White, a disparity explained by county demographics; 2) race-specific county-level violent crime strongly predicts the race of the civilian shot; and 3) although we find no overall evidence of anti-Black or anti-Hispanic disparities in fatal shootings, when focusing on different subtypes of shootings (e.g., unarmed shootings or “suicide by cop”), data are too uncertain to draw firm conclusions.

(Although political pressures led the authors of this study to “retract” the article, they did not deny their original conclusions or statistical approach.) As Jason Riley writes of the study:

why should anyone be surprised that young black men are far more likely than their white peers to be shot by police when young black men commit homicides at nearly 10 times the rate of white and Hispanic young men combined? “One of our clearest results is that violent crime rates strongly predict the race of the person fatally shot,” write the [study] authors. Moreover, “reducing race-specific violent crime should be an effective way to reduce fatal shootings of Black and Hispanic adults.” More minority cops might help law enforcement build trust in certain communities, but the “data suggest that increasing racial diversity would not meaningfully reduce racial disparity in fatal shootings.” Minority officers are no less likely to draw their weapons on minority suspects.

As reported in the Wall Street Journal, the 2021 report from the nonpartisan Bureau of Justice Statistics found no evidence at all of systemic racism in policing:

In a report released days before Mr. Biden’s inauguration, the Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Statistics examined whether people of different races were arrested to a degree that was disproportionate to their involvement in crime. The report concluded that there was no statistically significant difference by race between how likely people were to commit serious violent crimes and how likely they were to be arrested. In other words, the data suggested that police officers and sheriff’s deputies focus on criminals’ actions, not their race.

The BJS report did not take cops’ word for who commits crimes. Rather, it relied on victims’ own accounts of who committed crimes against them, as reported through BJS’s National Crime Victimization Survey.

The NCVS, which dates to the Nixon administration, is the nation’s largest crime survey. Its results are based on about 250,000 interviews annually with U.S. residents, who are asked whether they were victims of crime within the past six months. In addition, the NCVS gathers data on who actually commits crimes—according to the victims—thereby providing an independent source of data not reliant upon police records.

The new BJS report took victims’ responses on the 2018 NCVS and compared them with arrest rates by police, supplied by the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program. It found that for nonfatal violent crimes that victims said were reported to police, whites accounted for 48% of offenders and 46% of arrestees. Blacks accounted for 35% of offenders and 33% of arrestees. Asians accounted for 2% of offenders and 1% of arrestees. None of these differences between the percentage of offenders and the percentage of arrestees of a given race were statistically significant. (The data is limited to nonfatal crimes because murder victims cannot identify their assailants.)

Those statistics exclude Hispanics. The White House Office of Management and Budget classifies Hispanics as an ethnic rather than a racial group. Hispanics made up 13% of offenders and 18% of arrestees, a statistically significant difference. But because about 10% of victims were unable to determine whether their assailants were Hispanic or not, it is likely that victims classified some Hispanic offenders as white, or perhaps black, rather than Hispanic.

When removing simple assault, which generally isn’t prosecuted as a felony, and focusing solely on the more serious nonfatal crimes reported to police (rape or sexual assault, robbery and aggravated assault), whites made up 41% of offenders and 39% of arrestees. Blacks made up 43% of offenders and 36% of arrestees. Asians made up 2.5% of offenders and 1.5% of arrestees. Again, none of these differences between offenders and arrestees by race were statistically significant. Hispanics accounted for 12% of offenders and 21% of arrestees, which was statistically significant. But again, “victims not knowing the ethnicity of their assailants, even if they knew their race,” to quote the BJS report, “may have resulted in some underestimates of Hispanic offenders’ involvement in violent crime.”

These statistics don’t indicate that police officers are never racist. Individual officers, like people in any profession, run the gamut from laudable to deplorable. But what they do show is that Mr. Biden’s claim of “systemic racism” in American police forces is contrary to the best data we have on the subject.

Yet rhetoric to the contrary in the media and among politicians has led many Americans to opinions on the subject at odds with reality. As Douglas Murray writes in his book War on the West:

Actual public understanding of the issue turned out to be wildly, provably, out of sync with reality. For instance, when US citizens were polled and asked how many unarmed black Americans they believed had been shot by police in 2019, the numbers were off by several orders of magnitude. Twenty-two percent of people who identified as “very liberal” said they thought the police shot at least ten thousand unarmed black men in a year. Among self-identified liberals, fully 40 percent thought the figure was between one thousand and ten thousand. The actual figure was somewhere around ten. By proportion of the population, unarmed black Americans were slightly more likely to be shot by the police than unarmed white Americans. But as figures compiled by the Washington Post Police Shootings database confirm, in the years before the death of George Floyd, more police officers were killed by black Americans than unarmed black Americans were killed by the police ... [I]t is worth pointing out a potentially unpopular but nevertheless crucial fact about this origin story. Which is that there is still no evidence that the killing of George Floyd was a racist murder. At the trial of Derek Chauvin, no evidence was produced to suggest that it was a racist murder. If there had been any such evidence—that Chauvin harbored deep animus against black Americans and set out that May morning hoping to murder a black person—then the prosecution chose to make no such evidence available at Chauvin’s trial.

Presenting context like the following tends to be avoided by the news media. Zac Kreigman, formerly of Thompson Reuters, was made to leave that news service for pointing out that:

Statistics from the most complete database of police shootings (compiled by The Washington Post) indicate that, over the last five years, police have fatally shot 39 percent more unarmed whites than blacks. Because there are roughly six times as many white Americans as black Americans, that figure should be closer to 600 percent, BLM activists (and their allies in legacy media) insist. The fact that it’s not—that there’s more than a 500-percentage point gap between reality and expectation—is, they say, evidence of the bias of police departments across the United States. But it’s more complicated than that. Police are authorized to use lethal force only when they believe a suspect poses a grave danger of harming others. So, when it comes to measuring cops’ racial attitudes, it’s important that we compare apples and apples: Black suspects who pose a grave danger and white suspects who do the same. Unfortunately, we don’t have reliable data on the racial makeup of dangerous suspects, but we do have a good proxy: The number of people in each group who murder police officers. According to calculations (published by Patrick Frey, Deputy District Attorney for Los Angeles County) based on FBI data, black Americans account for 37 percent of those who murder police officers, and 34 percent of the unarmed suspects killed by police. Meanwhile, whites make up 42.7 percent of cop killers and 42 percent of the unarmed suspects shot by police—meaning whites are killed by police at a 7 percent higher rate than blacks. If you broaden the analysis to include armed suspects, the gap is even wider, with whites shot at a 70 percent higher rate than blacks. Other experts in the field concur that, in relation to the number of police officers murdered, whites are shot disproportionately … On an average year, 18 unarmed black people and 26 unarmed white people are shot by police. By contrast, roughly 10,000 black people are murdered annually by criminals in their own neighborhoods.

Finally, a 2023 meta-analysis of over 50 studies on the issue of policing and racial bias concluded there was no evidence of systemic bias, with the authors of the study writing:

It is widely reported that the US criminal justice system is systematically biased in regard to criminal adjudication based on race and class. Specifically, there is concern that Black and Latino defendants as well as poorer defendants receive harsher sentences than Whites or Asians or wealthier defendants. We tested this in a meta-analytic review of 51 studies including 120 effect sizes. Several databases in psychology, criminal justice and medicine were searched for relevant articles. Overall results suggested that neither class nor race biases for criminal adjudications for either violent or property crimes could be reliably detected … Studies with citation bias produced higher effect sizes than did studies without citation bias suggesting that researcher expectancy effects may be driving some outcomes in this field, resulting in an overestimation of true effects. Taken together, these results do not support beliefs that the US criminal justice system is systemically biased at current. Negativity bias and the overinterpretation of statistically significant “noise” from large sample studies appear to have allowed the perception or bias to be maintained among scholars, despite a weak evidentiary base. Suggestions for improvement in this field are offered. Narratives of “systemic racism” as relates to the criminal justice system do not appear to be a constructive framework from which to understand this nuanced issue.

That concludes this series of essays on race and the police. In the next series of essays, we’ll examine data regarding discrimination against women.