Regarding the genesis of “tough on crime” policies, it's important to note that such policies in the 1990’s were promoted primarily by black residents living in high-crime urban areas, and their representatives. In Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America, Professor James Foreman writes extensively about the support for aggressive law enforcement in the black community to combat largely black-on-black crime. As Foreman writes:

I have tried to recover a portion of African American social, political, and intellectual history—a story that gets ignored or elided when we fail to appreciate the role that blacks have played in shaping criminal justice policy over the past forty years. African Americans performed this role as citizens, voters, mayors, legislators, prosecutors, police officers, police chiefs, corrections officials, and community activists. Their influence grew as a result of black progress in attaining political power, especially after the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. And to a significant extent, the new black leaders and their constituents supported tough-on-crime measures. To understand why, we must start with a profound social fact: in the years preceding and during our punishment binge, black communities were devastated by historically unprecedented levels of crime and violence …

African Americans have always viewed the protection of black lives as a civil rights issue, whether the threat comes from police officers or street criminals. Far from ignoring the issue of crime by blacks against other blacks, African American officials and their constituents have been consumed by it …

When [Eric] Holder [as chief prosecutor in Washington. D.C. in the 1990’s] told the audience at the Arlington Sheraton that 94 percent of black homicide victims were slain by black assailants, he was simply putting a number on a problem his audience knew well. A range of black voices—and not just from law enforcement—agreed with Holder that safety was a civil rights issue. “If we’re not safe within our homes, if we’re not safe within our person, then every other civil right just doesn’t matter,” said Wade Henderson, the head of the NAACP’s Washington office. In such times, when Holder asked other blacks to help him respond to black America’s “group suicide,” few would say no. That the call for pretext policing came from Eric Holder, a highly respected African American prosecutor, was also crucial. Black federal prosecutors are viewed with tremendous respect in majority-black communities …

[Eric] Holder’s standing lent him similar credibility when he spoke to black audiences about Operation Ceasefire [an aggressive policing program he administered as top prosecutor in Washington, D.C. in the 1990’s]. “I’m not going to be naïve about it,” he told an audience at a community meeting on upper Georgia Avenue. “The people who will be stopped will be young black males, overwhelmingly.” But, as he had done in his King Day speech, Holder argued that such concerns were outweighed by the need to protect blacks from crime. He took a similar tack when celebrating the first anniversary of Operation Ceasefire with officers from the city’s gun squads, which had seized 768 guns and $250,000 in cash and had made 2,300 arrests. Holder acknowledged that most of the arrestees were black. But he had no regrets, he told the assembled officers, and neither should they. “Young black males are 1 percent of the nation’s population but account for 18 percent of the nation’s homicides,” he said. “You all are saving lives, not just getting guns off the street.” Holder’s approach was embraced by the black police chiefs who were running departments in several major cities by the late 1990s. In response to allegations that police were engaged in racial profiling, Bernard Parks, the African American police chief in Los Angeles, said that racial disparities resulted from the choices of criminals, not police bias. “It’s not the fault of the police when they stop minority males or put them in jail,” said Parks. “It’s the fault of the minority males for committing the crime. In my mind it is not a great revelation that if officers are looking for criminal activity, they’re going to look at the kind of people who are listed on crime reports.” Charles Ramsey, who became D.C.’s police chief in 1998, agreed. “Not to say that [racial profiling] doesn’t happen, but it’s clearly not as serious or widespread as the publicity suggests,” Ramsey said. “I get so tired of hearing that ‘Driving While Black’ stuff. It’s just used to the point where it has no meaning. I drive while black—I’m black. I sleep while black too. It’s victimology.’”

These crimes aren’t imagined by residents. They were real. Going back to the 1970’s, William Julius Wilson refuted the notion that higher black incarceration rates were the result of racism, writing in The Truly Disadvantaged that:

if a higher rate of black incarceration is accounted for by a higher rate of arrests, the question moves back a step: is the racial disproportionality in United States prisons largely the result of black bias in arrest? Recent research in criminology demonstrates consistent relationships between the distribution of crimes by race as reported in the arrest statistics of the Uniform Crime Reports and the distribution based on reports by victims of assault, robbery, and rape (where contact with the offender was direct). “While these results are certainly short of definitive evidence that there is not bias in arrests,” observes [Alfred] Blumstein, “they do strongly suggest that the arrest process, whose demographics we can observe, is reasonably representative of the crime process for at least these serious crime types.”

As UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh writes:

As best we can tell,

· blacks appear to commit violent crimes at a substantially higher rate per capita than do whites;

· there seems to be little aggregate disparity between the rate at which blacks commit violent crimes (especially when one focuses on crimes where the victims say they reported the crimes to the police) and the rate at which blacks are arrested for crimes; and

· the black-on-black crime rate is especially high.

Of course, it’s always hard to measure what the actual crime rate is for any group (whether for purposes of claiming that the rates are similar or that they are different). Still, the most reliable data, to my knowledge, is generally the National Crime Victimization Survey, and the U.S. Justice Department Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that are based on that survey. Indeed, the link in the quoted sentence from the article goes to a source that relies on such data.

Because the NCVS surveys a large group of people about their experiences with crime victimization, it is not based on what is reported to the police and what the police do with it. (The Uniform Crime Reports is based on data from police departments, and is thus generally a less reliable measure of actual crime.) Naturally, there are possible sources of bias in victim reports. But the NCVS seems to be the best data we have, and I know of no better source that yields other results. (If you do know, please let me know.)

Here, then, is the data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics' Race and Ethnicity of Violent Crime Offenders and Arrestees, 2018, with regard to "rape/sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault":

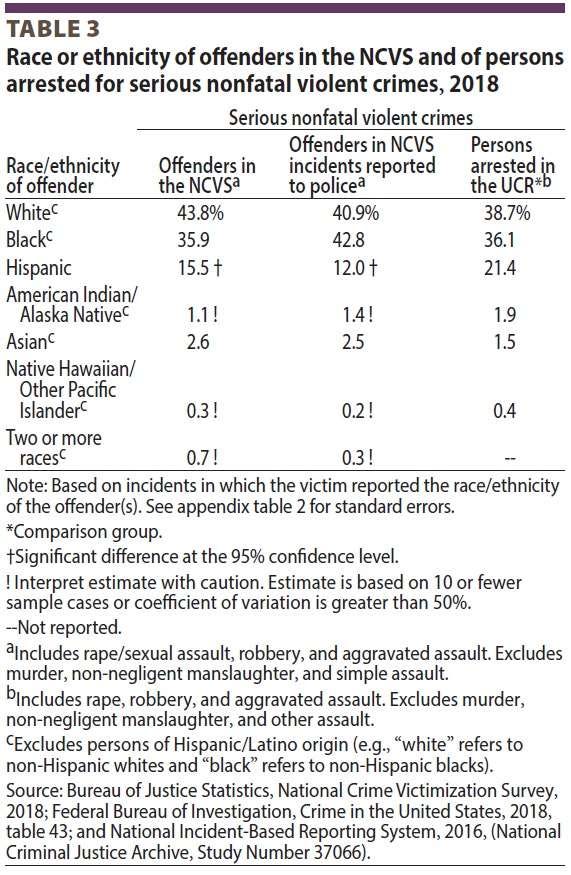

And here is the data for serious nonfatal violent crimes, which excludes simple assaults, and thus focuses on "rape/sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault":

Blacks, which here means non-Hispanic blacks, were 12.5% of the U.S. population, and non-Hispanic whites were 60.4%. It thus appears from this data that the black per capita violent crime rate is roughly 2.3 to 2.8 times the rate for the country as a whole, while the white per capita violent crime rate is roughly 0.7 to 0.9 times the rate for the country as a whole.

It also appears that the arrest rates for violent crime are roughly comparable to the rates of offending, especially if one takes into account those offenses reported to the police (which is a choice of the victims, not of police departments). And the great bulk of such violent crime is intraracial.

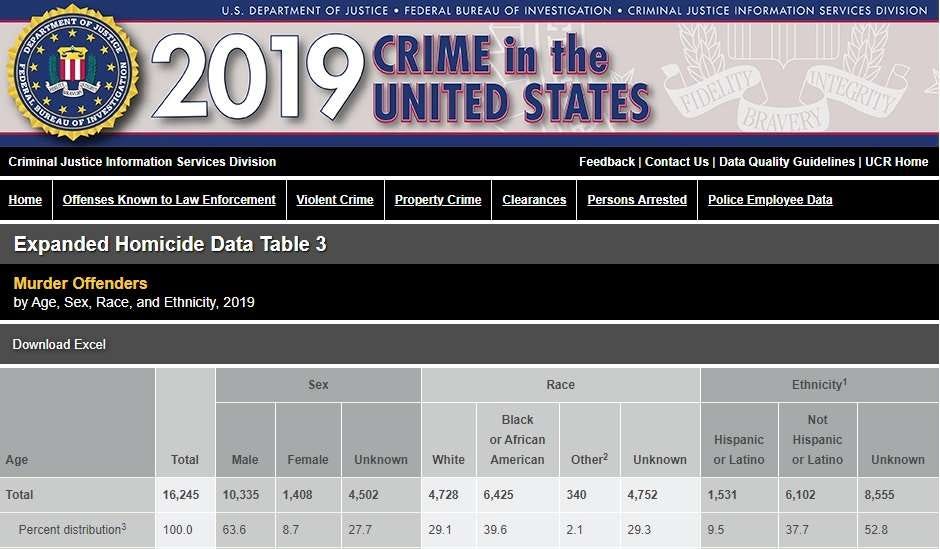

The disparity is even more striking for murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, which the NCVS doesn't measure (since the crime victim can't respond to the survey), and which thus relies on the police department reports in the UCR:

When the race of the offender was known, 55.9 percent were Black or African American, 41.1 percent were White, and 3.0 percent were of other races.

Here is the more specific data:

Many homicides are unsolved, and of course there is the risk of race-based investigation and enforcement. But again this is the best data we have, and it's consistent with victim demographics—it's clear that blacks are disproportionately likely to be murder victims—and the broadly accepted view that the overwhelming majority of homicide is intraracial.

Now naturally this reflects just aggregate statistics; the great majority of people in all racial groups don't commit violent crimes, and even the aggregate data may differ from place to place. Moreover, this doesn't tell us about property crimes (other than robbery, which is classified as a violent crime), because it's so hard to approximate the true rates of offense commission there: Most such property crimes are unwitnessed, so it's hard to gather survey data. And again, I'd love to hear any other data that might shed a different light on the violent crime statistics as well.

Still, the best data that I know of suggests that

· black-on-black violent crime is not a myth;

· blacks and whites generally commit violent crimes at substantially disparate rates (and, for homicides, sharply disparate rates); and

· as best we can tell, the disparity in arrest rates for violent crimes is pretty close to the disparity in crimes that are committed, and especially crimes that the victims report to the police.

As Charles Murray writes in his book Facing Reality:

The New York database of shootings is also useful as a counterweight to much of the rhetoric from the Black Lives Matter movement. Of course they matter, no matter what the race of the shooters in the New York database may be. That is my final point for this discussion. Many African lives have been taken by violence, but of the 1,906 African deaths in the New York shootings database for which the race of the perpetrator is known, 89 percent were killed by Africans. Ten percent were killed by Latins. Just 0.6 percent were killed by Europeans. Of the 7,858 Africans who were wounded in shootings, 90 percent were shot by Africans, 9 percent by Latins, and 0.4 percent by Europeans.

Regarding inter-racial violence generally, Heather MacDonald points out that:

whites are the overwhelming target of interracial violence. Between 2012 and 2015, blacks committed 85.5 percent of all black-white interracial violent victimizations (excluding interracial homicide, which is also disproportionately black-on-white). That works out to 540,360 felonious assaults on whites. Whites committed 14.4 percent of all interracial violent victimization, or 91,470 felonious assaults on blacks. Blacks are less than 13 percent of the national population.

This hasn’t always been the case. As Thomas Sowell writes in his book Discrimination and Disparities, “the black-white difference in homicide rates in various Northern communities during the first half of the nineteenth century was much smaller than it would become a century later.” Steven Pinker, in his book The Better Angels of Our Nature, also notes that:

In the northeastern cities, in New England, in the Midwest, and in Virginia, blacks and whites killed at similar rates throughout the first half of the 19th century. Then a gap opened up, and it widened even further in the 20th century, when homicides among African Americans skyrocketed, going from three times the white rate in New York in the 1850s to almost thirteen times the white rate a century later.

Interestingly, as certain urban governments have moved to reduce police presences in major cities, black gun ownership rates have gone up. As the Wall Street Journal reports in 2023, citing a survey by NBC News:

Twenty-four percent of black voters were in gun households in 2019. Today it’s 41%, up 17 points. Over the same period, the number for white voters rose three points, to 56% from 53%. Could this increase in black ownership be related to self-defense concerns amid the runup in urban crime? The survey doesn’t delve into the reasons, but it’s a reasonable guess. The NBC survey includes 1,000 registered voters, and the margin of error is plus or minus 3.1 points. But it fits other evidence, and the trend is hard to miss. The Second Amendment protects Americans who want to own firearms for self-defense, and lately millions more people have availed themselves of that right.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll look at data on police treatment of blacks.