Native Americans and North American History – Part 7

America’s emphasis on the agricultural improvement of land as a moral prerequisite to land ownership.

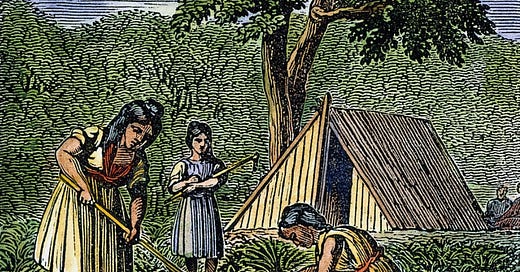

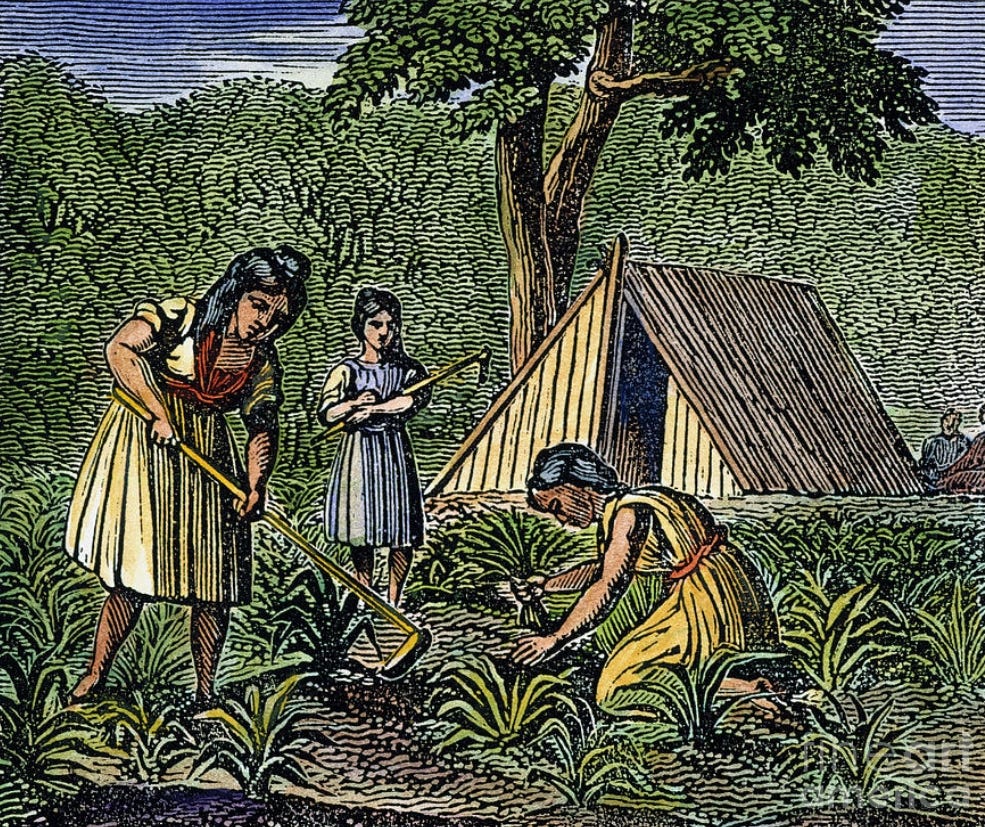

Native American gender roles affected how Americans came to see whether Native Americans were using their land for agriculture, or not, which in turn affected their perception of how much land Native Americans were entitled to, or not.

As Stuart Banner writes in his book How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier:

Indian agricultural techniques looked so different from the methods to which Americans were accustomed. The most glaring difference was that in most Indian communities farming was a task for women, not men. By the nineteenth century there was already a long Anglo-American tradition of criticizing Indian men as lazy and exploitative for this reason. When missionaries and others wishing to reform Indian life spoke of teaching the Indians to farm, what they often meant was teaching Indian men to farm. Within Indian communities, however, the social pressures to retain the traditional gendered division of labor could be very strong. It was often difficult for reformers to persuade Indian men to take up what they perceived as women’s work. And that was not the only difference between the two cultures in agricultural techniques. Traditional farming among the Cherokees, for example, did not employ plows or horses, or all the paraphernalia that went along with them. Cherokees were unaccustomed to farming in fields located far from towns, as Euro-Americans were. Indian tribes were learning to raise the animals Europeans had brought with them, animals like pigs and cattle that Euro-Americans instinctively interpreted as markers of a properly run farm. When reformers spoke of teaching the Indians to farm, they often meant teaching the Indians to farm differently -- in the Euro-American style. Many of the critics of traditional Indian agriculture were well intentioned. They were trying to help the Indians by making their farms more productive. But it could be easy for less-than-careful than careful observers of the Indians to conclude that they did not farm at all.

This understanding – that inefficient agricultural techniques gave Native Americans a lesser moral right to the land – was exemplified by John Quincy Adams:

In 1802, for example, John Quincy Adams, just beginning his political career, spoke of Indian property rights in a speech commemorating the anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing at Plymouth. No colony had been kinder to the Indians than Plymouth, Adams declared. The Pilgrims had purchased land rather than seizing it. “At their hands the children of the desert” -- that is, the “Indians – “had no cause of complaint.” Purchasing the land had been an act of generosity, Adams reasoned, because the Indians owned only a tiny fraction of it. “Their cultivated fields; their constructed habitations; a space of ample sufficiency for their subsistence, and whatever they had annexed to themselves by personal labor, was undoubtedly, by the laws of nature, theirs,” Adams conceded, in a Lockean style. But such land accounted for a very small percentage of the territory the Pilgrims purchased. Most land, insisted Adams, had been used for hunting. And “what is the right of a huntsman to the forest of a thousand miles over which he has accidentally ranged in quest of prey?” To recognize the Indians as owners of all that land would authorize them to refuse to sell it, which would endow the Indians with resources disproportionate to their numbers. “Shall the liberal bounties of Providence to the race of man be monopolized by one of ten thousand for whom they were created?” Adams asked. “Shall the exuberant bosom of the common mother, amply adequate to the nourishment of millions, be claimed exclusively by a few hundreds of her offspring?”

If vast swaths of land were simply ceded to Native Americans, Adams thought, what we see and enjoy today as vast technological and industrial progress wouldn’t have occurred:

Even worse, recognizing Indian ownership threatened to choke off progress in the new United States, because economic growth and the spread of civilization depended on access to all that land. Adams painted a dark picture of the consequences. “Shall the lordly savage not only disdain the virtues and enjoyments of civilization himself, but shall he control the civilization of a world?” Adams asked. Shall he forbid the wilderness to blossom like a rose? Shall he forbid the oaks of the forest to fall before the axe of industry, and to rise again, transformed into the habitations of ease and elegance? Shall he doom an immense region of the globe to perpetual desolation, and to hear the howlings of the tiger and the wolf silence forever the voice of human gladness? Shall the fields and the valleys, which a beneficent God has formed to teem with the life of innumerable multitudes, be condemned to everlasting barrenness? Shall the mighty rivers, poured out by the hand of nature, as channels of communication between numerous nations, roll their waters in sullen silence and eternal solitude of the deep? Have hundreds of commodious harbors, a thousand leagues of coast, and a boundless ocean, been spread in the front of this land, and shall every purpose of utility to which they could apply be prohibited by the tenant of the woods? Of course not, Adams concluded. The Indians were accordingly not the owners of their hunting grounds, but only of the land they actually cultivated and built houses on.

While this perspective had prominent adherents in America, it never became the law. As Banner writes:

Adams’s view never became the law. The United States would always recognize the Indians as holding some kind of right in their hunting grounds, even if it was not full ownership. But the opinion expressed by Adams seems to have grown more common in the years around 1800. Tennessee governor John Sevier, referring to the Indians, declared in 1798 that “by the law of nations, it is agreed that no people shall be entitled to more land than they can cultivate.” President James Monroe’s annual message to Congress in 1817 included a similar assertion. “The hunter state can exist only in the vast uncultivated desert,” Monroe explained. “It yields to the more dense and compact form and greater force of civilized population, and of right it ought to yield, for the earth was given to mankind to support the greatest number of which it is capable, and no tribe or people have a right to withhold from the wants of others more than is necessary for their own support and comfort.”

Still, this understanding, over time, led to Native Americans’ being “removed” to places they might more effectively farm, with the meaning of “removed” being less ominous than it is today:

Today, remove is virtually always a transitive verb. We usually think of removing something or someone, normally by the application of force. Before the twentieth century, however, the word had a second, intransitive sense, a meaning that has nearly disappeared today. Remove was almost synonymous with move, but it had the specific connotation of a relocation from one place to another. Macbeth, to pick a famous example, declares that he will not fear defeat “till Birnam Wood remove to Dunsinane.” Benjamin Franklin entitled his 1784 essay on emigration to the United States Information to Those Who Would Remove to America. In Jane Austen’s Emma (1816), Emma hears that Frank Churchill and his aunt “were going to remove immediately to Richmond,” a place more suitable for them than London. In this sense of the word, the subject of the sentence was doing the removing of its own accord. It was not being compelled to remove by someone else. In the early nineteenth century, when American officials spoke of the Indians removing to the west, they normally had the verb’s intransitive sense in mind … Removal simply meant emigration. The word lacked the overtones of force it would later acquire.

With that less menacing understanding of the term “remove,” Banner writes:

There were many white Americans who advocated removal because they genuinely believed it was in the best interests of the Indians … Everyone knew that the white population of the United States was constantly increasing and that white settlement was pushing steadily westward. Barring a dramatic change in the federal government’s Indian policy, the Indians’ future looked dismal. James Barbour, the secretary of war under President John Quincy Adams, was just one of many who recognized the looming catastrophe. “Shall we go on quietly in a course, which, judging from the past, threatens their extinction?” he asked in a thoughtful 1826 memorandum recommending removal. Or was there something the government could do to save the Indians? Many feared along with Barbour that there would soon be no Indians left unless the federal government protected them from extinction. The only way to do that, they argued, was to encourage the Indians to relocate far from white settlers. The annual report of the commissioner of Indian affairs was normally a dry statistical document, but in his report for 1828 Commissioner Thomas McKenney included an emotional appeal to Congress to act before it was too late. “What are humanity and justice in reference to this unfortunate race?” McKenney asked. Are these found to lie in a policy that would leave them to linger out a wretched and degraded existence, within districts of country already surrounded and pressed upon by a population whose anxiety and efforts to get rid of them are not less restless and persevering, than is the law of nature immutable, which has decreed, that, under such circumstances, if continued in, they must perish? Or does it not rather consist in withdrawing them from this certain destruction, and placing them, though even at this late hour, in a situation where, by the adoption of a suitable system for their security, preservation, and improvement, and at no matter what cost, they may be saved and blest? McKenney and others who were concerned about the fate of the Indians had motivations similar to those of the many people today who are concerned for endangered species of animals. Today it is widely believed that the government has a responsibility to protect animals from extinction, and that the best way to do that is to provide them a sanctuary where they will be safe from the noxious influences of civilization. In the early nineteenth century, long before there was common concern for the welfare of animals, many were worried about endangered human beings.

With many Native Americans unwilling to change their traditional ways of hunting, Banner writes:

It was only a matter of time before frontier state governments, answerable to white settlers bordering on Indian land, began ratcheting up the pressure on the non-selling tribes by threatening to make life considerably more difficult for Indians who refused to sell their land. That pressure, and the federal government’s response to it, gave rise to the series of events that has come to be remembered as “removal.” … It was this perceived need to keep Indians from interfering with white emigration that gave rise to the idea of confining the Indians to specified locations, but once the idea was in circulation, many suggested that it would benefit Indians as much as whites. As with some of the ostensibly humanitarian reasons offered for removal, some of the arguments in favor of confining the Indians to reservations were no doubt disingenuous. But whites were no more monolithic in their attitudes toward Indians in the 1840s and 1850s than they had been in earlier periods. As always, many were genuinely concerned with the Indians’ welfare. By the late 1850s, many such people were just as convinced as the most ardent Indian-haters of the desirability of moving Indians to reservations. Some argued that reservations would be the lesser of evils -- that the Indians would be killed unless they got out of the settlers’ way. “The border tribes are in danger of ultimate extinction,” [Luke] Lea [Commissioner of Indian Affairs] warned in 1850. “If they remain as they are, many years will not elapse before they will be overrun and exterminated.” The same weighing of alternatives had motivated the humanitarian support for removal back in the 1830s. In the 1850s, it suggested a form of internal removal, into areas where the Indians could be protected from the dangers of contact with whites. In 1856, when Commissioner of Indian Affairs George Manypenny looked back over a decade of growing western cities and expanding western railroads, he was apprehensive about the Indians’ future. They would be “blotted out of existence,” Manypenny predicted, “unless our great nation shall generously determine that the necessary provision shall at once be made, and appropriate steps be taken to designate suitable tracts or reservations of land, in proper localities, for permanent homes for, and provide the means to colonize, them thereon.” Proponents of moving the Indians to reservations could sincerely think of themselves as humanitarians, as people altruistically interested in the Indians’ well-being rather than their own … By the early 1850s, for all these reasons, federal Indian policy turned to the reservation. Virtually all Indian land cessions from then on resulted in the designation of a circumscribed area in which the selling tribe was to live … The federal government no longer simply purchased land from the Indians, as settlers had done since the early 1600s. Now land transactions typically had two components, a cession from the Indians to the United States and the delineation of a reservation for the Indians. Many of the reservations were created by treaty …”

The desire for designated national parks that would preserve natural areas from the influence of both Native American and settlers alike also motivated Native American removal polices:

Between the 1850s and 1880s, the federal government acquired Indian land at unprecedented speed. By 1870 all the land in Iowa, Minnesota, Texas, and Kansas had either been ceded to the government or designated as a reservation. By 1880 the same was true of Idaho, Washington, Utah, Oregon, Nevada, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Colorado; by 1886 it was also true of Montana, Arizona, and New Mexico. It had taken whites 250 years to purchase the eastern half of the United States, but they needed less than 40 years for the western half … At the same time, whites’ growing interest in experiencing uninhabited “natural” landscapes caused the federal government to acquire even more Indian land, to be set aside as national parks once the Indians had been expelled.

Complete list of essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10.