Native Americans and North American History – Part 5

Written contracts and fraud on both sides.

As we continue to explore how Native Americans lost their land through Stuart Banner’s book How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, Banner describes the many opportunities for misunderstandings among English settlers and Native Americans:

[D]ifferences in the way members of the two cultures understood land transactions were most likely exacerbated by differences in how they understood the significance of writing. The English practice had long been to memorialize an agreement in writing, and to think of the writing as the best evidence of what the parties had agreed to. The Indians lacked writing. Theirs was an oral culture, in which events were often remembered in the form of stories. In the early transactions the Indians would have had no reason to suppose that in the event of a future dispute the English would privilege the written contract over the memories of the participants, or that oral promises on the part of the English were less likely to be fulfilled than written promises. Many of the early English settlers could not read or write either, to be sure, but they at least had a sense of the way their own culture treated written documents. This difference may have added to the mismatch between English and Indian interpretations of early sales.

Some of these issues may have been ameliorated over time by experience, and increased literacy among Native Americans:

[O]ne might reasonably suspect that a single misunderstood transaction would have been enough to drive the point home, not just for the tribe caught by surprise but also for other tribes even at a great distance. The news of what the English meant by a sale most likely reached many areas in advance of the English themselves. In the earliest purchases in any location the Indians were probably victims of cross-cultural misunderstanding, but it is unlikely that the tribes in any given area could have been misled repeatedly … In some places, repeated contact between the English and the Indians brought Indian property practices closer to English practices. Missionaries spread literacy along with Christianity. By the early eighteenth century the percentage of literate speakers of the Massachusett language may have been higher than the percentage of settlers who could read or write English. Indians in the area around Boston began conveying land to one another with written contracts. Written records began as confirmations of earlier oral agreements, but they seem eventually to have been executed at the same time as oral agreements to convey land, just like written contracts among the English.

Still, fraud occurred, but it occurred on both sides:

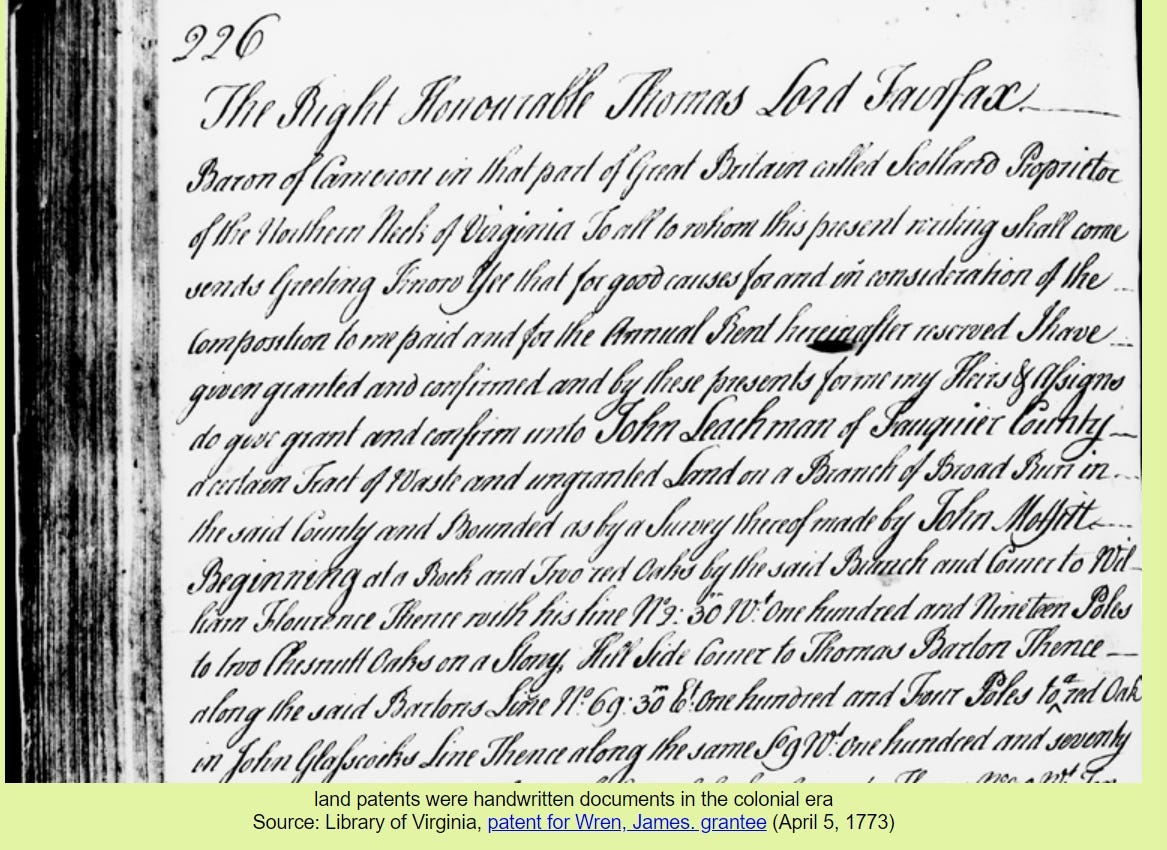

Fraud could take many shapes. In several cases English purchasers told the Indians they wished to buy parcels of a given size but then, without alerting the Indians, inserted in the deeds descriptions of parcels much larger. As one duped seller complained, “when a Small parcel of Land is bought of us a Large Quantity is taken instead.” Cadwallader Golden, surveyor general of New York in the 1730s (and later governor), reported that such deception was possible because “the Indians have been perswaded to sign these Deeds without having them interpreted by persons sufficiently Skill’d in the English and Indian languages.” Devious purchasers could also slip misdescriptions of the land past Indian sellers, Golden explained, by drafting deeds to express boundaries not in terms of natural landmarks but “by points or Degrees of the Compass pass & by English Measures which are absolutely unknown to the Indians.” By the middle of the eighteenth century, as a result of this pattern of fraud, New York and Virginia (and perhaps other colonies as well) required that land purchased from Indians be first surveyed by a government surveyor in the presence of the selling tribe.

Native Americans committed fraud as well. As Banner writes:

[T]he largest share of Indian losses from land sales may have been attributable to a different kind of problem. There was no clear answer to a question that in most markets is easily answered: Who had the right to sell? The Indians did not sell land before the English arrived, so they had no reason to develop rules or customs governing exactly who had the authority to enter into a land sale. Suddenly confronted with offers to purchase land, the Indians had to improvise such principles on the fly … Did an individual have the authority to sell the parcel he had the exclusive right to cultivate? Did he need the permission of the tribe before selling his parcel? Could the leader of a tribe sell his tribe’s land? Did he need the permission of the tribe as a whole? The permission of all the individual tribe members whose property rights would be affected? The prospect of selling land gave rise to some urgent questions of internal tribal organization, questions that had never come up before … There was considerable disagreement within individual tribes as to exactly who had the authority to sell. “Some lands have been bought by the proprietor or his agents from Indians who had not a right to sell,” the Delaware chief Teedyuscung told Pennsylvania governor William Denny in 1757. Teedyuscung’s complaint was a common one -- that individual Indians had sold tribal land without the consent of the tribe.

Incentives for fraud among Native Americans included the following:

An individual tribe member, confronted with an offer to purchase land, might have had a personal incentive to sell even where the good of the tribe would not be advanced by selling. Had the Indians been able to prevent unauthorized land sales, tribes could have held out for higher prices. Instead, individual tribe members, knowing that their authority to sell land might be called into question by the tribe, and aware that fellow tribe members might simultaneously be trying to sell the very same land, had every incentive to accept purchase offers quickly, and were thus more likely than tribes as a whole to sell at low prices. Although it is impossible to quantify the losses the Indians suffered from this problem, a simple model of the purchasing process suggests that the losses could easily have amounted to a significant part of the value of the land sold.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore how coming to treat Native American tribes as sovereign entities affected their loss of land.

Complete list of essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4; Part 5; Part 6; Part 7; Part 8; Part 9; Part 10.

Thanks, Dr. K! Very much appreciated!

Paul, I have learned more history in an area about which I clearly knew too little from your pieces than I ever expected. This is a great series on a topic that should have more exposure than it gets. Many thanks for doing this.