In this essay, we’ll examine the effects of education on economic inequality.

In a previous essay series, we explored the largely disproportionate benefits received by women generally compared to men in education. Now, as Phil Gramm, Robert Ekelund, and John Early write in their book The Myth of American Inequality: How Government Biases Policy Debate, we can also see how those disproportions are reflected in measures of economic inequality:

The natural progression of economic development from human muscle power to animal power, to machine power, to knowledge power not only created more jobs requiring more education but also made education a greater differentiator in earning power, which, in turn, has increased the inequality of earned income … Beginning in the 1960s, women’s share of new college degrees started to grow more rapidly, surpassed the number granted to men in 1982, and reached 57.2 percent of the total by the turn of the millennium. It has stayed roughly at that level for almost twenty years. The proportions of masters and doctorate degrees earned by women have followed a similar pattern. By 1987, women earned 50.4 percent of master’s degrees, and that percentage hit 60.3 percent in 2007, where it stabilized. Doctorates earned by women (including advanced professional degrees in medicine and law) reached 50.1 percent in 2005 and continued to climb to 53.8 percent by 2017, the last year for which data are available … Numerous social and economic studies have shown that in addition to causing work effort in lower-income households to plummet, greater transfer payments have weakened the formation of two-income households.40 As a result, two-earner households have become a smaller proportion of the bottom two quintiles, and the inequality of earned income has increased. At the middle and upper end of the income distribution, as more women entered the labor market, they created greater household earnings by expanding the number of two-earner households … Highly educated women and men tend to marry or form households with those possessing similar levels of education who earn similar incomes. As a result, the rise in college graduates also has led to a sharp increase in the number of households with two highly educated people, sometimes called “super two-earner households.” This increased concentration of earning power is one of the reasons for the growth in earned-income inequality … By 2017, 29.5 percent of all households were headed by two college graduates, and 74.2 percent of all college graduates were in two-graduate households. The incidence of the super two-earner households had exploded from only one in twenty households to almost one in three. This greater concentration of college-educated couples in super two-earner households alone accounted for 8.1 percent of the increase in the inequality of earned household income from 1967 to 2017. When political activists denounce the rise in earned-income inequality, they are neglecting the fact that a significant portion of the phenomenon they decry has arisen from the individual efforts of women and their greater participation in the economy.

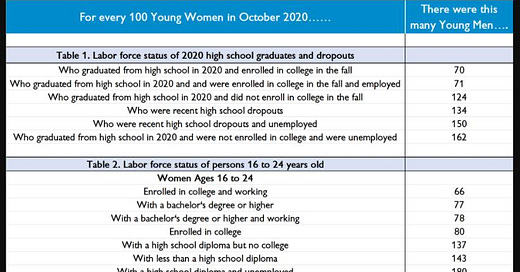

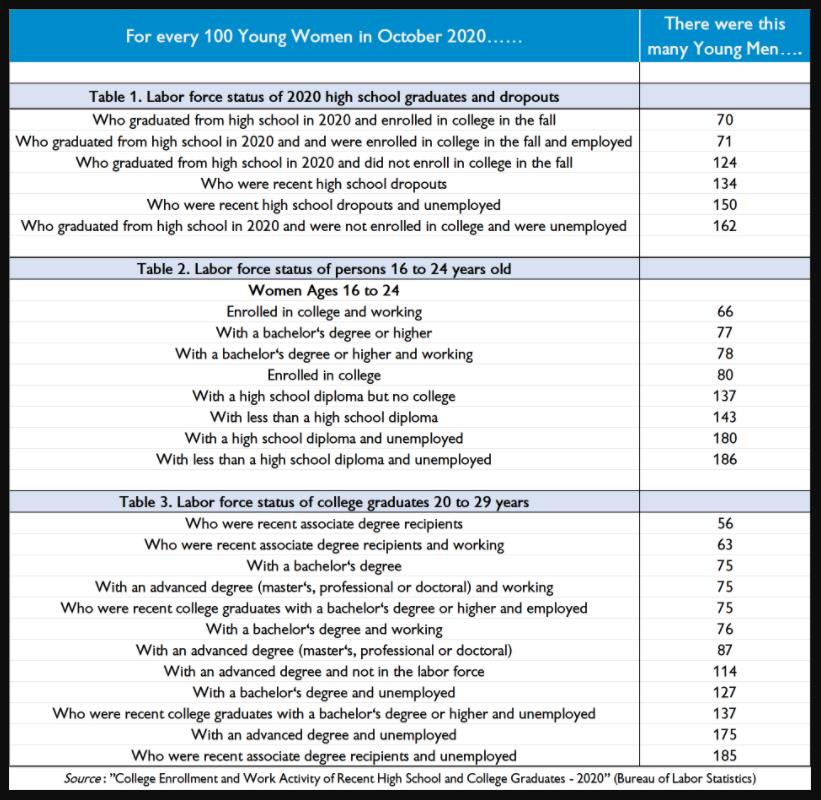

Mark Perry of the American Enterprise Institute points to the following Bureau of Labor Statistics annual report on “College Enrollment and Work Activity of Recent High School and College Graduates – 2020” based on data as of October 2020.

Specifically, the data in the chart above show that:

Compared to young women, young men were less likely to graduate from high school, more likely to drop out of high school, less likely to enroll in college after high school and more likely to be unemployed. For example, for every 100 females who graduated from high school last year and enrolled in college in the fall of 2020, there were only 70 young men. For every 100 young women who were recently dropped out of high school, there were 134 young men; Compared to women ages 16 to 24, men in that age group were less likely to be enrolled in college, far less likely to have earned a bachelor’s degree or higher, and far less likely to be employed with a college degree. Compared to young women in that age group, young men were far more likely to have less than a high school diploma, much less likely to attend college after high school and more likely to be unemployed with or without a high school diploma. For example, for every 100 young women ages 16-22 who were enrolled in college and working last fall, there were only 66 young men; Compared to females ages 20-29 years old who recently earned an associate’s degree or hold a bachelor’s or advanced degree (master’s, professional or doctoral), their male counterparts were far less likely to have recently earned an associate’s degree, less likely to hold a bachelor’s or advanced (master’s, professional or doctoral) college degree and far less likely to have a college degree (bachelor’s degree or higher) and be employed. Young men ages 20-29 who were recent associate degree recipients, recent college graduates with a bachelor’s degree or higher, and those who with a bachelor’s or advanced degree were far more likely to have those degrees and be unemployed than their female counterparts. For example, for every 100 women who were recent associate degree recipients, there were only 56 men. For every 100 women with an advanced degree who were unemployed, there were 175 men.

The authors of The Myth of American Inequality add that:

The significant gender differences favoring young women for a variety of educational outcomes detailed above provide additional empirical evidence that it is men who are increasingly struggling to finish high school and attend and graduate from college. Actually, men have been increasingly underrepresented and “marginalized” in higher education for 40 years going back to the early 1980s. And young women are more likely than their male counterparts to be working after earning a college degree. College-educated young men with any degree (associate’s, bachelors, or advanced) are more likely than female college graduates to be either unemployed or not in the labor force … It is young men, more than young women, who are at-risk and facing serious educational and work-related challenges, which show up later in large gender disparities for a variety of measures of (a) behavioral and mental health outcomes, (b) alcoholism, drug addiction, and drug overdoses, (c) suicide, murder, violent crimes, and incarceration, and (d) homelessness.

The authors of The Myth of American Inequality also explore the role of occupational choice in economic inequality (a topic touched on in a previous essay):

Occupational choice was the most important factor determining the differences in hourly earnings among individuals with the same level of education in 2017 … Differences in education on average accounted for about 30 percent of the difference in earned income from work. Occupational choice within an educational level added another 7 percent and experience accounted for about 2 percent … Among full-time workers who worked less than 40 hours per week, women earned 4 cents more than men. Among part-time workers, women made 6 cents more. So the only place where an actual “pay gap” existed was for those working 40 or more hours per week. For those working fewer hours, women made more. Just as more experience creates pay inequality in the population generally, experience accounts for a significant part of the gender pay gap. Women, on average, have worked fewer years than men of the same age. Women between the ages of forty-three and fifty-one, on average, had nearly three fewer years of work experience compared with men of the same age, giving men 13 percent more experience and adding another 5 cents to the pay gap. The time lost from work for child rearing also explains why, on average, women who have not married had only a 9-cent pay gap, married women had a 22-cent gap, and those who were widowed, divorced, or separated had an 18-cent gap. As in other group comparisons, occupational choices also affect relative earnings. Women work at almost every type of job, but they are still more likely to work in occupations that on average pay less. Of course, it would be equally true that men, on average, work in the occupations that pay more. Women are, as a matter of fact, less likely to hold jobs in areas such as commission sales and finance that have greater financial risk of periods with lower earnings, although in the long run the pay may be higher.54 Similarly, there are fewer women in jobs that entail greater physical danger and offer significant premium pay. Men are nine times more likely to hold a job with known physical risks, seventeen times more likely to hold jobs exposing them to fumes, eight times more likely to work in extreme weather, and almost five times more likely to hold jobs exposing them to high levels of noise. As a result, men have twelve times the workplace fatality rate of women and 50 percent more workplace injuries … For those occupational choices that required a postsecondary education, the choice of college major had a significant effect. A Georgetown University study found that only one of the ten top-earning college majors had a majority of women as graduates. More women than men selected nine of the ten lowest-earning majors. And two economists from the University of Michigan found that in addition to selecting courses that specifically prepare them for higher-paying occupations, men were more likely to make course selections that were associated with higher pay, with an effect large enough to account for about 1.5 cents of the pay gap. Hours worked, experience, selection of occupations, and educational choices explain all but 1.5 cents of the 17-cent gender pay gap.

As the authors summarize these educational effects:

[A]n additional 11.7 percent increase in earned-income inequality can be explained by the increased disparities in educational attainment. Finally, between 1967 and 2017, the premium in earnings received for having a college degree nearly doubled … [A]dding the higher college premium explains about a 5.2 percent increase in earned-income inequality … In short, earned-income inequality has risen because some people have been induced to work less by the availability of greater government transfer payments, while others have worked more to promote their households’ well-being. An increasing proportion of Americans have achieved higher levels of education, and the value of that education has grown. Women have entered the labor force in greater numbers, dramatically increasing the number of two-earner households in the top 60 percent of households. And highly educated high achievers have tended to marry or otherwise form households with each other. Those who are the most vocal critics of our economic system for its growth in earned-income inequality in postwar America are also often the most committed advocates of expanding the very transfer payments to low-income Americans that have been the largest cause of the growth in earned-income inequality. They also have been the biggest promoters of the public education system that has left so many behind and the greatest critics of education reforms, such as school choice, that enable more children to raise their future earnings.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine other research that adds yet more context to the discussion of economic inequality.