Math’s Path – Part 4

Testing without fully understanding the test or why the test is being given.

In the last essay we looked at the stark partisan differences among people’s thresholds of risk during the COVID pandemic. This seems to be a new phenomenon.

The acceptance of relatively small risk by the vast majority of people (that is, those without special preexisting conditions significantly increasing their risk) used to be bipartisan. As Michael Barone has explained:

Vaclav Smil, 76, native of communist Czechoslovakia, University of Manitoba professor for four decades, has written 39 books on energy, technology, and demography. “Nobody,” says Bill Gates, who has read every one, “sees the big picture with as wide an aperture as Vaclav Smil.”

And Vaclav Smith has written that the extended lockdown approach to COVID-19 is far in excess of the approach taken during previous, more deadly, pandemics:

What I find strange is that the unfolding COVID-19 event has prompted relatively few references to the three latest pandemics, for which we do have good numbers …

Yet it is remarkable that these more virulent pandemics had such evanescent economic consequences. The United Nations’ World Economic and Social Surveys from the late 1950s contain no references to a pandemic or a virus. Nor did the pandemics leave any deep, traumatic traces in memories. Even if one very conservatively assumes that lasting memories start only at 10 years of age, then 350 million of the people who are alive today ought to remember the three previous pandemics, and a billion people ought to remember the last two. But I have yet to come across anybody who has vivid memories of the pandemics of 1957 or 1968. Countries did not resort to any mass-scale economic lockdowns, enforce any long-lasting school closures, ban sports events, or cut flight schedules deeply … Why were things so different back then? Was it because we had no fear-reinforcing 24/7 cable news, no Twitter, and no incessant and instant case-and-death tickers on all our electronic screens? Or is it we ourselves who have changed, by valuing recurrent but infrequent risks differently?

Indeed, as of January, 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control’s numbers, out of the more than 867,000 people who died “with” COVID-19 (and that’s not necessarily dying “of” COVID), only 1,150 were under age 18. But analyses showed that 1,282 children died from the H1N1 pandemic of 2009-2010, when Barack Obama was President and Joe Biden was Vice President. Yet relatively few people have even heard of H1N1, either back in 2009-2010, as it was happening, or today.

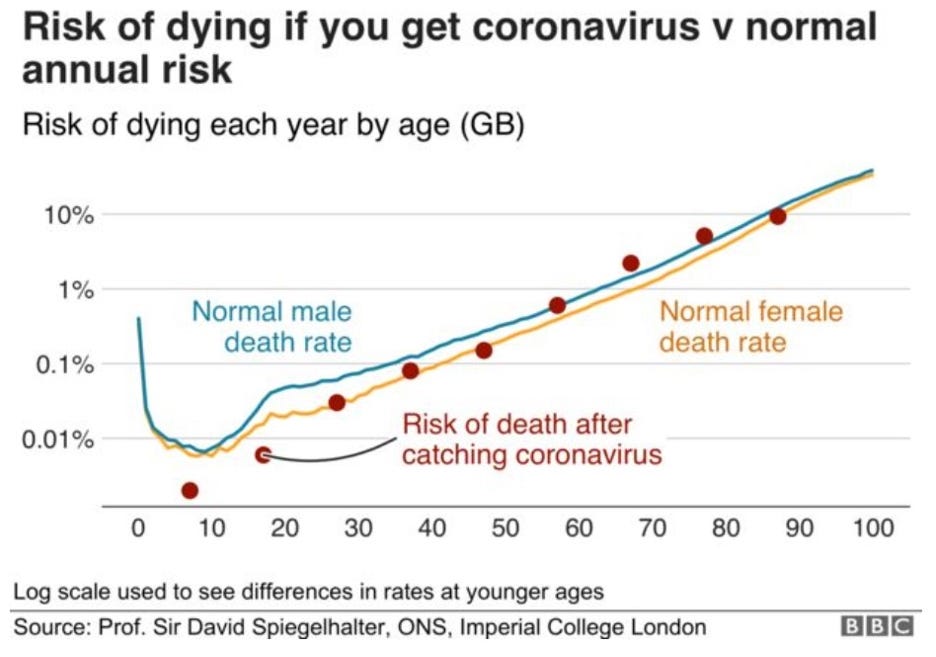

To get a better sense of risk exposure on the individual level, the BBC produced the following chart, which shows the general rise in the risk of mortality from COVID-19 (compared to the pre-COVID-19 baseline risk) by age.

As elaborated:

Those with pre-existing health conditions are most at risk. Deaths among under-65s with no illnesses are "remarkably uncommon", research shows. Perhaps the easiest way is to ask yourself to what extent you are worried about the thought of dying in the next 12 months. What is remarkable about coronavirus is that if we are infected our chances of dying seems to mirror our chance of dying anyway over the next year, certainly once we pass the age of 20. For example, an average person aged 40 has around a one-in-1,000 risk of not making it to their next birthday and an almost identical risk of not surviving a coronavirus infection. That means your risk of dying is effectively doubled from what it was if you are infected. And that is the average risk - for most individuals the risk is actually lower than that as most of the risk is held by those who are in poor health in each age group. So coronavirus is, in effect, taking any frailties and amplifying them. It is like packing an extra year's worth of risk into a short period of time. If your risk of dying was very low in the first place, it still remains very low. As for children, the risk of dying from other things - cancer and accidents are the biggest cause of fatalities - is greater than their chance of dying if they are infected with coronavirus. During the pandemic so far three under 15s have died. That compares to around 50 killed in road accidents every year.

And as explained in the Wall Street Journal:

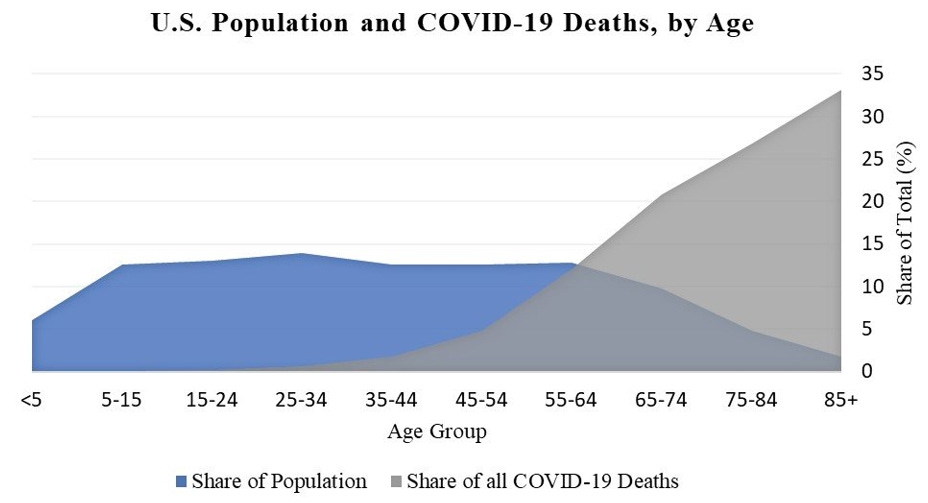

This virus disproportionately harms older Americans. It is estimated that upward of 50% of deaths have been in nursing homes. Roughly 30% have been people over 65 not in nursing homes, and the other 20% is everyone else, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. That means roughly 3% of all nursing-home residents have died of Covid-19, versus 0.06% of people over 65 not in nursing homes and 0.01% of the rest of the population. If we separated the generally healthy population under 65 from the medically vulnerable under 65 the numbers would be even more stark. This set of facts about who is most vulnerable must inform our approach to reopening.

The following chart illustrates the distribution of COVID-19 deaths by age compared to the age distribution of all Americans. While just 16.4 percent of the population is aged 65 or older, they represent 80.7 percent of the COVID-19 fatalities.

Yet many people have become obsessed not only with the risks associated with COVID, but also with the perceived need for testing even asymptomatic younger people for COVID -- even as its strains grow weaker and its impact on the young remains exceedingly small.

Michael Brooks, in his book The Art of More: How Mathematics Created Civilization, addresses the importance of math in evaluating the effectiveness of COVID testing as follows:

A similar problem has arisen in testing populations for Covid-19 in the recent viral pandemic. In an imperfect world, a test that is “99 per cent accurate” sounds close enough to perfect, doesn’t it? So, we should surely use it to test everyone, whether or not they have symptoms? … But that’s potentially a very bad judgement call. Let’s say one person in every thousand actually has Covid-19, and we’re testing 1,000 people. A test with 99 per cent accuracy will give the right answer to 99 per cent of people who are sick, and to 99 per cent of those who are healthy. That means it will give a positive result to 1 per cent of the remaining 999 people who don’t have Covid. That’s a whopping 9.99 people … And that’s with all the information. When you don’t actually know the prevalence of Covid-19 in the population, you don’t know how many false positives you’re getting.

And some antigen tests administered at schools are giving false negatives, with one study concluding “Based on viral load and transmissions confirmed through epidemiological investigation, most Omicron [variant] cases were infectious for several days before being detectable by rapid antigen tests.” In some places, including where I live, there’s a bit of a panic over testing for COVID that’s causing parents to sign their kids up for free weekly testing programs at school, regardless of whether the kids have any symptoms -- and the kids who’ve been signed up are waiting in lines for tests, missing recess and half of their classes that follow recess. (And math also tells us those “free” COVID tests aren’t actually free; they’re paid by the insurance companies, which, as noted in the Wall Street Journal, “will inevitably pass the costs on to policyholders through either higher premiums or reduced benefits … [T]he $1,140 per month for testing at my daughter’s preschool … would add up to $13,860 [annually] —a sum that comes close to the $14,974 average yearly expenditure per student in California public schools.”)

And this all at a time when it’s being realized that the emphasis on “case counts” amid the now-predominant Omicron strain is misguided. Here’s the Associated Press: “case numbers seem to yield a less useful picture of the pandemic amid the spread of omicron, which is causing lots of infections but so far does not appear to be as severe in its effects.”

The Associated Press also reports that:

The [AP] has recently told its editors and reporters to avoid emphasizing case counts in stories about the disease … Hospitalization and death rates are considered by some to be a more reliable picture of COVID-19′s current impact on society. Yet even the usefulness of those numbers has been called into question in recent days. In many cases, hospitalizations are incidental: there are people being admitted for other reasons and are surprised to find they test positive for COVID, said Tanya Lewis, senior editor for health and medicine at Scientific American … There are some in public health and journalism who believe the current surge — painful as it is — may augur good news. It could be a sign that COVID-19 is headed toward becoming an endemic disease that people learn to live with, rather than being a disruptive pandemic, wrote David Leonhardt and Ashley Wu in The New York Times.

In Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk, Peter Bernstein writes of how, in the 1600’s, people began to grapple more carefully with the concept of risk as they never had before:

In 1662, a group of [Pascal’s] associates at the [Port-Royal] monastery published a work of great importance, “La logique, ou l’art de penser” (“Logic, or the Art of Thinking”), a book that ran to five editions between 1662 and 1668. Although its authorship was not revealed, the primary— but not the sole— author is believed to have been Antoine Arnauld … The book was immediately translated into other languages throughout Europe and was still in use as a textbook in the nineteenth century … The last part of the book contains four chapters on probability … The author admits that the games he has described [in the book] are trivial in character, but he draws an analogy to natural events. For example, the probability of being struck by lightning is tiny but “many people ... are excessively terrified when they hear thunder.” Then he makes a critically important statement: “Fear of harm ought to be proportional not merely to the gravity of the harm, but also to the probability of the event.” Here is another major innovation: the idea that both gravity and probability should influence a decision … The Port-Royal author argues that only the pathologically risk-averse make choices based on the consequences without regard to the probability involved.

Regarding COVID-related risks, as discussed in a previous essay, kids are more likely to be killed in a car accident, commit suicide, be murdered, drown, or be accidentally poisoned, and seniors are as likely in any given year to die in a fire or from falling down stairs. (Bryan Caplan sets out the risk of death from COVID to kids in more detail in this post here.)

As Bernstein writes of those who are overly risk-averse:

Think of what life would be like if everyone were phobic about lightning, flying in airplanes, or investing in start-up companies. We are indeed fortunate that human beings differ in their appetite for risk.

Yet today, some planners seem to want to run with any numbers presented to them in a chart (including Omicron “case counts”), regardless of their larger context which might render them misleading. And organizations like the American Federation of Teachers have an interest in exploiting inaccurate perceptions of risk in communities to maintain restrictive COVID practices. Marla Ucelli-Kashyap, a representative of AFT, made clear that “One thing that’s really important for us to know is that … actual safety and the perception of safety both really matter,” even adding that “that’s where things like the impact of structural racism … come into play.” (See at the 36:20-minute mark in this video here.)

I’ll conclude this series with a short anecdote. As Bernstein writes, Kenneth Arrow, who went on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1972, had the following experience early in his army career:

One incident that occurred while Arrow was forecasting the weather [at a military base] illustrates both uncertainty and the human unwillingness to accept it. Some officers had been assigned the task of forecasting the weather a month ahead, but Arrow and his statisticians found that their long-range forecasts were no better than numbers pulled out of a hat. The forecasters agreed and asked their superiors to be relieved of this duty.

And what did the statisticians receive as a reply from their superiors? It was as follows: “The Commanding General is well aware that the forecasts are no good. However, he needs them for planning purposes.”

Links to all essays in this series: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3; Part 4