Locus of Control – Part 3

Is a greater sense of external locus of control running from high school up through national politics?

In previous essays I’ve quoted Stephen Nowicki’s book Choice or Chance: Understanding Your Locus of Control and Why It Matters, which describes the psychological concept of “locus of control,” a concept designed to describe the degree to which we expect what happens to us, good or bad, is connected to our behavior. Various data show that those with a more internal locus of control tend to be happier than those with a more external locus of control. But what of its effects on political outlooks?

Professor Nowicki gave a lecture on the subject of locus of control and was asked (at the 1:15:45 second mark) “Do you think there’s any relationship between internal and external and political orientation?” Nowicki responded, “Believe it or not, the most internal people are white Republican males. That’s just what the data are.” I tend to believe it.

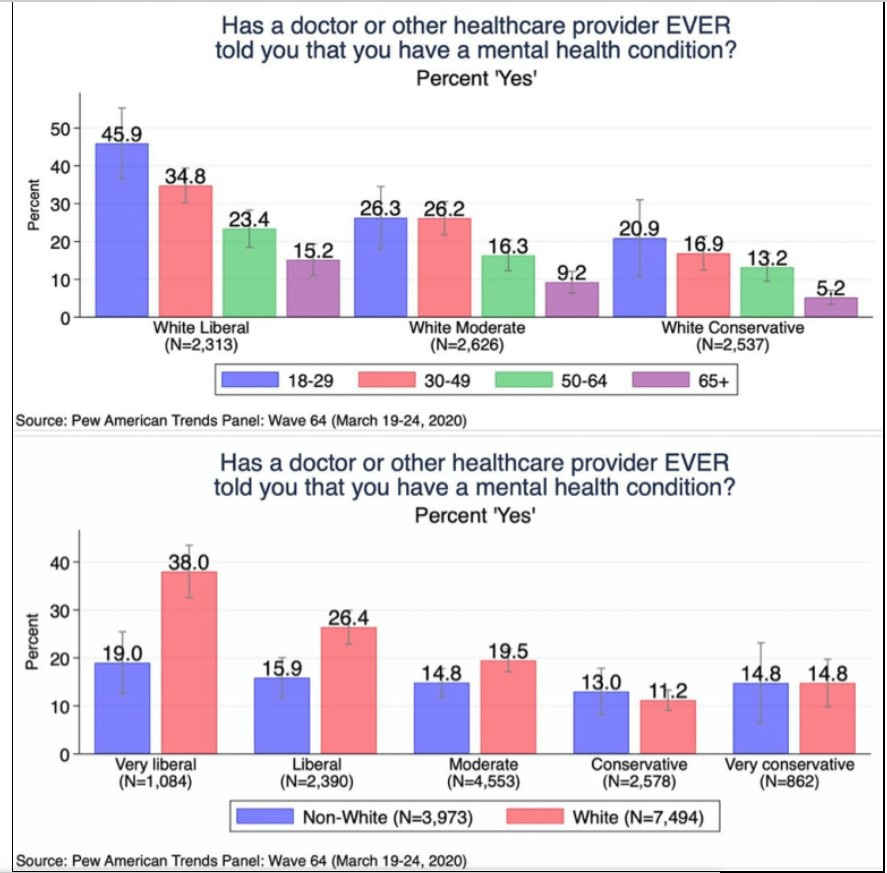

Liberals are more than twice as likely as conservatives to be found to have a mental health condition.

Other research shows that

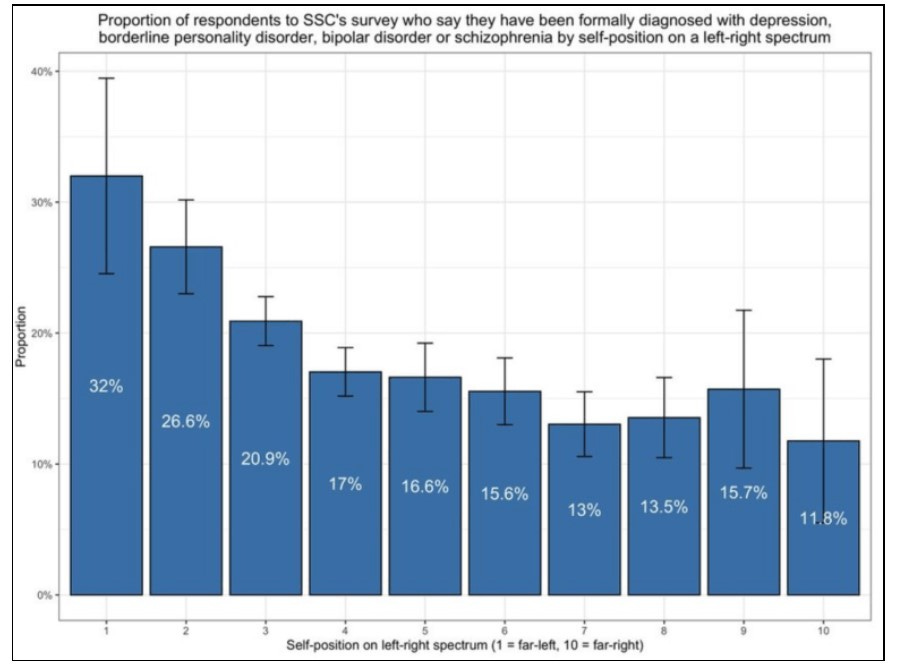

It has been claimed that left-wingers or liberals (US sense) tend to be more mentally ill than right-wingers or conservatives. This potential link was investigated using the General Social Survey. A search found 5 items measuring one’s own mental illness in different ways (e.g. ”Do you have any emotional or mental disability?”). All of these items were associated with left-wing political ideology as measured by self-report. These results held up mostly in regressions that adjusted for age, sex, and race. For the variable with the most data, the difference in mental illness between “extremely liberal” and “extremely conservative” was 0.39 d. This finding is congruent with numerous findings based on related constructs.

As reported by Greg Lukianoff in March, 2024 and May, 2024:

The data shows that ideology, race and gender are all statistically significant predictors of self-reported mental health, with liberals having the worst self-reported mental health compared to moderates and conservatives, and women having worse self-reported mental health than men. What’s more, the interaction between race, ideology, and gender is statistically significant — with liberal white and non-white women having the worst self-reported mental health. This trend has also been reported by Zach Goldberg and Haidt using Pew Research’s data, as well as findings from Gimbrone et al … [A]s students move further to the left, they are more likely to have poor mental health — suggesting that it’s not just liberal ideology that impacts mental health, but also the extremity of their beliefs. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests show ideology is a statistically significant predictor of mental health. Post-hoc tests demonstrate it predicts in the direction as shown: more liberal, worse mental health.

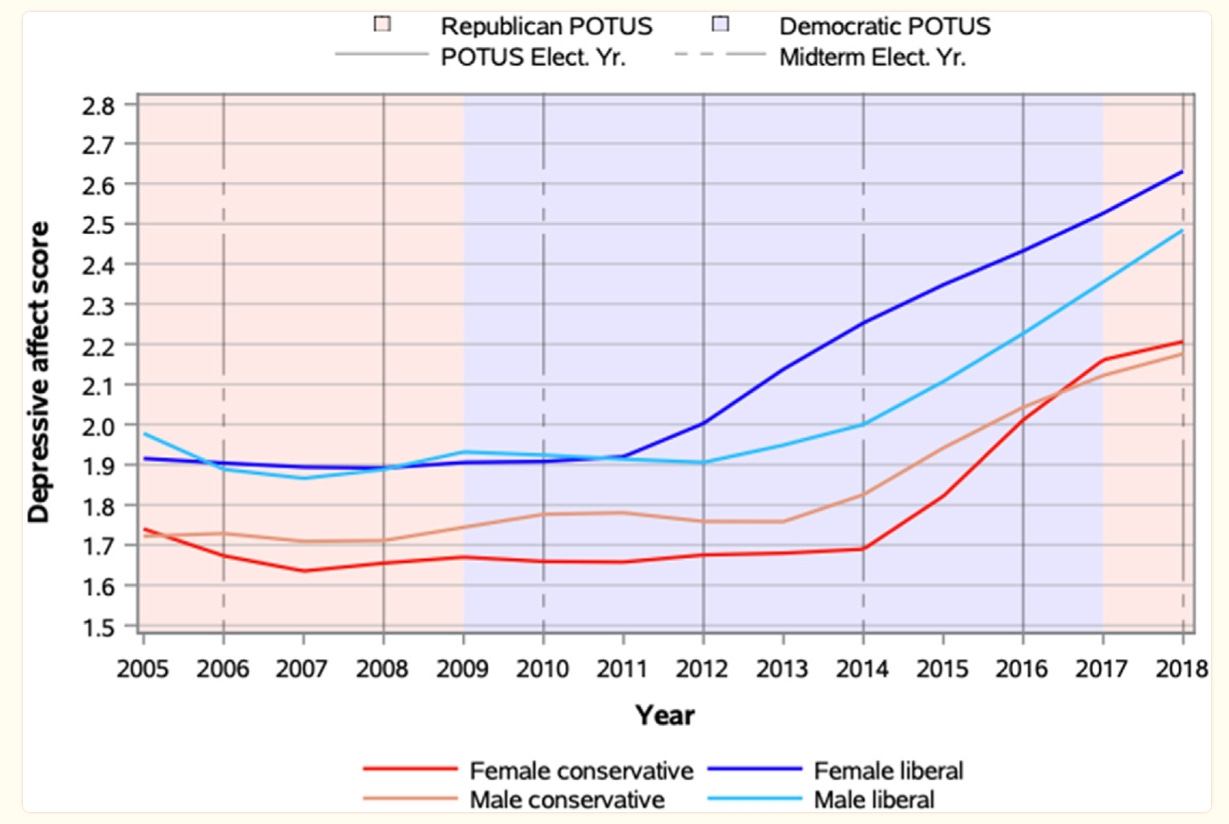

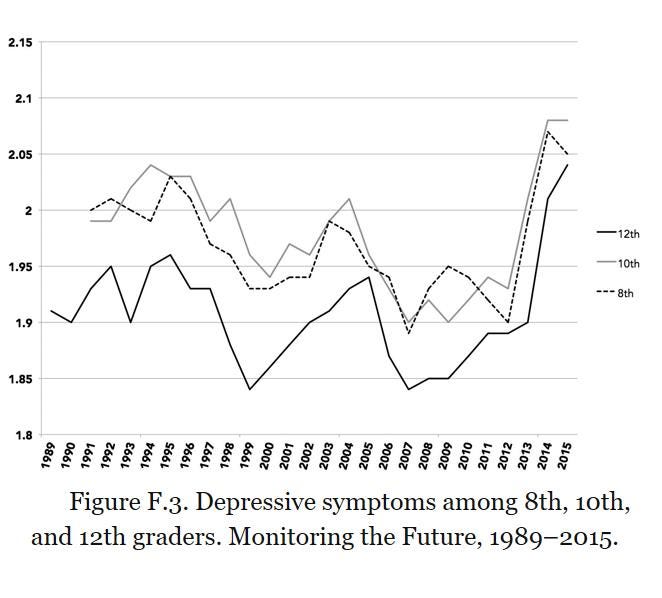

As Gimbrone and others write in their paper “The Politics of Depression”:

We analyzed nationally-representative data from 2005 to 2018 Monitoring the Future annual cross-sectional samples of 12th-grade students (N = 86,138). We examined self-reported political beliefs, sex, and parental education as predictors of four internalizing symptom scales over time, including depressive affect. From 2005 to 2018, 19.8% of students identified as liberal and 18.1% identified as conservative, with little change over time. Depressive affect (DA) scores increased for all adolescents after 2010, but increases were most pronounced for female liberal adolescents (b for interaction = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.32), and scores were highest overall for female liberal adolescents with low parental education (Mean DA 2010: 2.02, SD 0.81/2018: 2.75, SD 0.92). Findings were consistent across multiple internalizing symptoms outcomes. Trends in adolescent internalizing symptoms diverged by political beliefs, sex, and parental education over time, with female liberal adolescents experiencing the largest increases in depressive symptoms, especially in the context of demographic risk factors including parental education. These findings indicate a growing mental health disparity between adolescents who identify with certain political beliefs.

Researchers have found that campaigns that tend to associate general distress with depression and other mental disorders can actually produce those disorders where they didn’t exist before:

[A]wareness efforts are leading some individuals to interpret and report milder forms of distress as mental health problems. We propose that this then leads some individuals to experience a genuine increase in symptoms, because labelling distress as a mental health problem can affect an individual's self-concept and behaviour in a way that is ultimately self-fulfilling. For example, interpreting low levels of anxiety as symptomatic of an anxiety disorder might lead to behavioural avoidance, which can further exacerbate anxiety symptoms. We propose that the increase in reported symptoms then drives further awareness efforts: the two processes influence each other in a cyclical, intensifying manner.

As Derek Thompson writes in the Atlantic:

People who keep hearing about new mental-health terminology—from their friends, from their family, from social-media influencers [or their schools]—start processing normal levels of anxiety as perilous signs of their own pathology. “If people are repeatedly told that mental health problems are common and that they might experience them … they might start to interpret any negative thoughts and feelings through this lens,” [Lucy] Foulkes and [Jack] Andrews wrote. This can create a self-fulfilling spiral: More anxiety diagnoses lead to more hypervigilance among young people about their anxiety, which leads to more withdrawal from everyday activities, which creates actual anxiety and depression, which leads to more diagnoses, and so on.

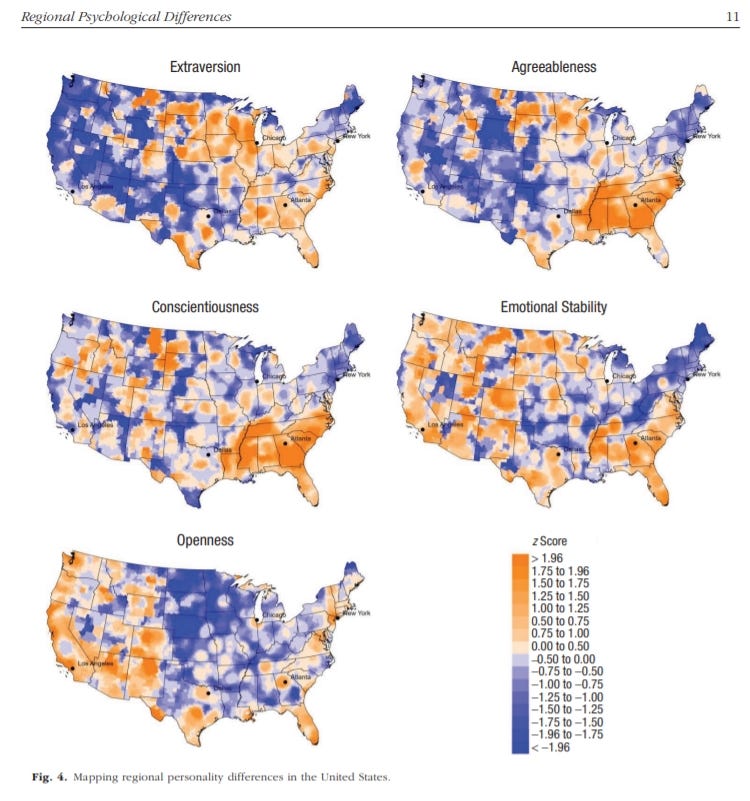

People in Southern states tend to be more Republican, and, consistent with the above data, researchers have found that “regional psychological differences are robust and can reliably be studied across countries and spatial levels,” and those results show that residents of Southern States generally rank highest on the psychological traits of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability.

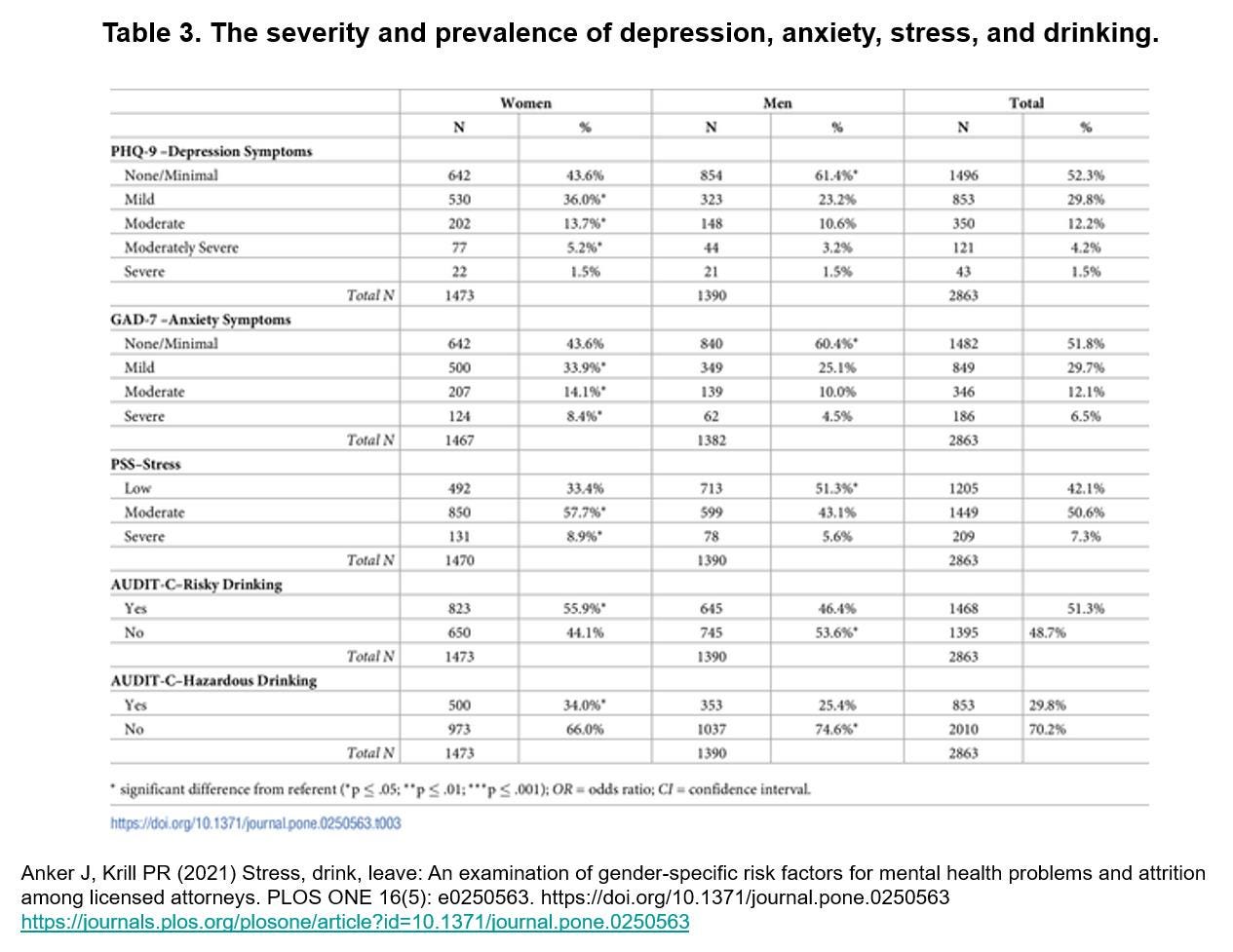

The legal profession in California and Washington, D.C. is dominated by people generally aligned with the Democratic Party, and when researchers examined lawyers in Washington, D.C. and California they found the following:

Rates of mental illness and heavy alcohol use are exceedingly high in the legal profession, while attrition among women has also been a longstanding problem … Data were collected from 2,863 lawyers randomly sampled from the California Lawyers Association and D.C. Bar … Findings indicated that the prevalence and severity of depression, anxiety, stress, and risky/hazardous drinking were significantly higher among women. Further, one-quarter of all women contemplated leaving the profession due to mental health concerns, compared to 17% of men.

Younger people have always tended to be of a politically liberal orientation, at least in more modern times, and at the same time there’s been an increase in depressive symptoms among high school students.

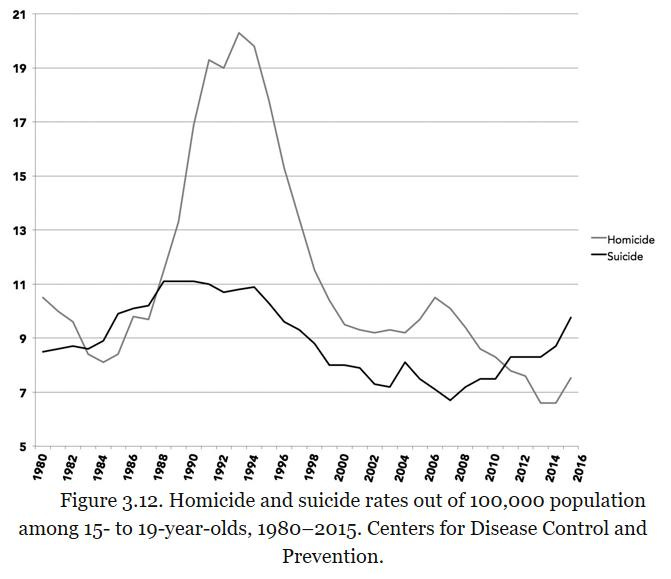

There has also been an increase in the suicide rate among young people even as the homicide rate among young people has declined.

As if in synch, popular music appears to have gotten sadder and angrier over the years.

Interestingly, the general trend toward depression among high schoolers is less pronounced among those who live in rural and suburban areas, which tend to be less liberal politically.

Entering college students have, in turn, increasingly reported mental health issues.

Many of these young people go on to become some of the most influential activists in Democratic Party politics.

The harmful focus on an external locus of control has even worked its way into presidential rhetoric. Democratic President Joe Biden, when referring to America, has replaced the phrase "land of opportunity" with "land of possibility." While the former connotes the sort of "seize the opportunity" mindset associated with the beneficial internal locus of control, the latter connotes the sort of "life is a crap shoot subject mainly to outside forces" mindset associated with the more harmful external locus of control.

Also, letting constant distractions (including those caused by social media that perpetuate feelings of an external locus of control) prevent people from taking time out to process their thoughts can perpetuate negative thoughts and emotions. As Julian Adorney and Mark Johnson write:

[A] way to reduce conflict is to take some time away from the conflict to breathe. As psychologist Chris Ferguson explained to us in an interview, doing this can help us to calm down and not fly off the handle at small conflicts. Ferguson explains that "there are two related issues here…emotional responses usually peak immediately after a stressor, then lessen with time, and, second, emotional responses tend to impair problem-solving." "Thus," he argues, "you see people have a bad emotional response, impulsively do something stupid, only to later acknowledge how stupid it was." When we pause and take time to process, we can "evaluate if the situation is really as bad as we initially thought it was" and calibrate our response from there ... In ages past, humans had lots of idle time. We fished, sharpened spears, tended fires, repaired nets, and performed other physical activities that kept our hands busy while leaving our minds free to process the events of the day. By contrast, in the modern world, we have little to no idle time. Every spare minute is filled with distractions: we listen to podcasts, read books, text friends, and check social media ten thousand times per day. As a result, we never actually process our emotions and work through them.

One anecdote in concluding this series. Last March a neighbor let me know about a free book giveaway that was being run in someone’s front yard. I went up to check it out and there were around a dozen tables and many more boxes filled with books that people were looking through on the lawn. I thanked the people running it and took a few books for myself. But I was struck by the immense volume of books whose themes focused on all the negatives in America’s history, to the apparent exclusion of any bright side. There were many hundreds of these books, all with the sort of “antiracist” focus embodied by the New York Times bestselling books of Ibram X. Kendi and Robin Diangelo, or similar oppression-focused narratives. My neighbor and I shared the titles of the books we’d taken for ourselves, and then my neighbor said he spoke to the people running the give-away. They said the books had been owned by someone who committed suicide.

Indeed, Over a dozen researchers conducted a study that specifically examined the effects on young people of Ibram X Kendi’s and Robin DiAngelos’s way of framing the world. They found the following: The study looked at three different types of DEI training, on religion, race and caste. For the experiment on race, they used material taken from books written by Ibram Kendi and Robin DiAngelo. A control group was presented with a neutral text about the farming of corn.

The Ibram X Kendi and Robin DiAngelo excerpt read as follows: “White people raised in Western society are conditioned into a white supremacist worldview. Racism is the norm; it is not unusual. As a result, interaction with White people is at times so overwhelming, draining, and incomprehensible that it causes serious anguish for People of Color.”

The Control Text (Corn Excerpt) read as follows: “America has just about 90 million planted acres of corn, and there’s a reason people refer to the crop as yellow gold. In 2021, U.S. corn was worth over $86 billion, based on calculations from FarmDoc and the United States Department of Agriculture. According to the USDA, the U.S. is the largest consumer, producer, and exporter of corn in the world.”

Rutgers students read one excerpt or the other and were then presented with a brief story: "A student applied to an elite East Coast university in Fall 2024. During the application process, he was interviewed by an admissions officer. Ultimately, the student’s application was rejected." Participants were then asked if the story demonstrated racism. Those who'd read the Kendi or DiAngelo passage were much more likely to attribute discrimination to the admissions officer even though race was never mentioned in that brief story at all, indicating the passaging primed people to see even racism where there is no evidence of its existing in a given circumstance. Those who'd read the Kendi or DiAngelo passage were also more likely to advocate punitive measures, such as suspending the admissions officer or mandating additional “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” training.

As Thomas Sowell writes in Social Justice Fallacies:

Some emphasis on racism can even be counterproductive. President Barack Obama related an experience he had when talking with a black young man who wanted to become a pilot. This young man at first thought of joining the U.S. Air Force, in order to get trained to be a pilot. But then he said he realized that the Air Force “would never let a black man fly a plane.” This was said decades after there was a whole squadron of black American fighter pilots during World War II— and, in later years, two black pilots went on to become generals in the U.S. Air Force. Whoever indoctrinated this young man did him more harm than a racist could have, by keeping him from even trying to become a pilot.

All educators should consider whether or not their methods of teaching are tending to encourage people to view the world is a place of injustice and danger or a place of opportunity and freedom, because those worldviews have serious life consequences. As Robert Pondiscio writes:

Maya is 13 years old and in eighth grade. First period is English, where her class is reading a young adult novel about a teenage girl who self-harms, spirals into depression, and eventually attempts suicide. Her teacher praises the book for its honesty and “unflinching emotional truth.” After a brief discussion, the class writes about how trauma shapes identity. Second period is social studies. Today’s reading assignment comes from the 1619 Project, followed by a worksheet asking students to reflect on how racism is “baked into the structure of American life.” Last week, students read a chapter from A People’s History of the United States, by Howard Zinn, and discussed whether the U.S. was founded to protect the wealthy at the expense of everyone else. Maya takes notes quietly, worried she might say the wrong thing. In science, the class is studying climate change. The teacher plays a documentary that includes images of wildfires, melting glaciers, and disappearing coastal towns. Maya learns that humanity will face catastrophic collapse if global carbon emissions do not reach “net zero” by the time she’s in her thirties. During lunch, she tells a friend she’s not sure she wants to have kids someday. In the afternoon, Maya joins her “action civics” project group. Their capstone project is about gun violence. They’re creating a slide deck and organizing a letter-writing campaign. The project guidelines encourage students to “identify a systemic injustice” and “propose a structural solution.” Her group adviser urges them to “center” their personal stories. Tomorrow is a half day. Teachers will spend the afternoon in professional-development workshops on “trauma-informed pedagogy,” where they’ll learn to spot signs of anxiety, disengagement, and despair in students — and to treat these as evidence of trauma. Almost no one will consider the possibility that we are the ones traumatizing students. If you spend time in American classrooms today, especially in schools shaped by the dominant ideas of social and emotional learning (SEL) and trauma-informed pedagogy (TIP), you might get the impression that the world is a broken and dangerous place — and that wise and loving adults equip children to navigate it successfully by making them aware of just how bad things are. We think we’re helping them. But what if we’re not? That question lies at the heart of a compelling and underappreciated body of research led by Jeremy Clifton, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania … Clifton’s research has not made its way into teacher-training programs, education-policy debates, or district SEL initiatives. The only mention I’ve found of it in a publication aimed at teachers is a 2022 Education Week interview in which Clifton offered a quiet warning: “Don’t assume teaching young people that the world is bad will help them. Do know that how you see the world matters.” This quiet warning, if heeded, could spark a revolutionary change in American education. It could also guide those seeking to respond more productively to the mental health crisis afflicting America’s children. That crisis is no longer abstract or emerging — it is measurable, visible, and urgent. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 40 percent of high school students reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless in 2021, up from 28 percent a decade earlier. Nearly one in five seriously considered suicide. Among girls, the numbers are even more dire: Nearly 60 percent reported persistent sadness or hopelessness, and 30 percent said they had considered suicide. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association have jointly declared this a national emergency. Schools are at the front lines of this crisis. Yet our default response — more SEL, more trauma awareness, more therapeutic intervention — may be managing the symptoms while reinforcing the cause … In studies published in the Journal of Positive Psychology and other journals, Clifton and co-author Peter Meindl found that negative primal beliefs were strongly associated with anxiety, cynicism, depression, suicidal ideation, and less life satisfaction. By contrast, people with sunnier beliefs — those who saw the world as safe and enticing — tended to report dramatically better outcomes across the board, including greater life satisfaction, more emotional resilience, better physical health, stronger interpersonal relationships, and lower levels of anxiety and depression. The widespread belief that viewing the world as dangerous fosters vigilance and success is, Clifton and Meindl found, unsupported. If you work in education — or have a child in school — you’ve probably encountered the growing emphasis on trauma-informed pedagogy. This approach, born of legitimate concern for children who’ve experienced adversity, encourages teachers to consider trauma as a key explanation for misbehavior or disengagement. In practice, it can lead to lower expectations, less structure, and a default posture of therapeutic intervention rather than academic instruction. Social and emotional learning, too, has evolved far from its original goal of helping children navigate their emotions. In many schools, SEL has become the central organizing principle of classroom culture: “emotional check-ins,” “restorative circles,” “safe spaces,” and constant reminders that children are “not okay” — that they carry trauma, or live in an unjust world, or must always be on guard against microaggressions and existential threats. Summarizing [Clifton’s] work, Arthur Brooks wrote in The Atlantic, “No doubt these beliefs come from the best of intentions. If you want children to be safe (and thus, happy), you should teach them that the world is dangerous — that way, they will be more vigilant and careful. But in fact, teaching them that the world is dangerous is bad for their health, happiness, and success.” … To be clear, none of this is an argument for rose-colored glasses. Children need to know that the world contains hardship, injustice, and danger. But they also need to know that it contains beauty, opportunity, and meaning — and that history contains a record of genuine progress and that further progress remains possible. And only one of those orientations leads reliably to flourishing. As Clifton puts it, “There’s beauty everywhere — we have only to open our eyes to see it.” But someone must show children how.

A report by the Network Contagion Institute at Rutgers University states that:

[T]olerance - and even advocacy - for political violence appears to have surged, especially among politically left-leaning segments of the population … 31% and 38% of respondents stated it would be at least somewhat justified to murder Elon Musk and President Trump … These effects were driven by respondents that self-identified as left of center, with 48% and 55% at least somewhat justifying murder for Elon Musk and President Trump, respectively … Our analysis supports the belief that BlueSky [a social media platform] plays a significant and predictive role in amplifying radical ideation.

Interestingly, the same report finds that:

Being left of center and authoritarian emerged as a key predictor [of support for political violence] of all models, use of Blue Sky and external locus of control were common predictors as well … [E]xternal locus of control—the belief that one’s outcomes are shaped by outside forces—was linked to greater support for violence …”

In many ways we live out our lives under a narrative structure of our own choosing. So we should all make sure we’re considering as much context as possible before settling on a negative narrative that may not only be based on false assumptions, but also have tragic consequences.