Law Professors on Impeachment

Why did law professors have pretty much uniformly one-sided views on the impeachment of Secretary Mayorkas?

In the last essay, I discussed the grounds for the impeachment of the Secretary of Homeland Security. Whenever the media described that impeachment, it was typically reported that “constitutional experts have said the policy criticisms outlined by Republicans do not meet impeachment's high standard of misconduct.”

Whenever the subject of impeachment comes up, reporters start calling law professors to get their views on it. And in modern times a remarkable pattern emerges. Law professors overwhelmingly support the impeachment of Republicans, and overwhelmingly oppose the impeachment of Democrats. Why is that?

As law professor Jonathan Turley wrote in 2022:

A new study offers further evidence of the alarming decline of ideological diversity on our law faculties. A study by Georgetown University’s Kevin Tobia and MIT’s Eric Martinez was featured on College Fix that finds that only nine percent of law school professors identify as conservative at the top 50 law schools. Notably, a 2017 study found 15 percent of faculties were conservative. This is the result of years of faculty replicating their own ideological preferences and eradicating the diversity that once existed on faculties. When I began teaching in the 1980s, faculties were undeniably liberal but contained a significant number of conservative and libertarian professors. It made for a healthy and balanced intellectual environment. Today such voices are relatively rare and faculties have become political echo chambers, leaving conservatives and Republican students increasingly afraid to speak openly in class … Having taught for over three decades, I have never seen a more intolerant and orthodox environment. Schools have reached an ideological critical mass where faculties are replicating their own preferences. The overwhelming composition of faculties then serves to replicate and promote the views of liberal faculty on journals and in conferences … Even if one quibbles with these polls, most faculty will privately admit that there are few remaining conservatives or Republicans on their faculties. It is obvious and undeniable.

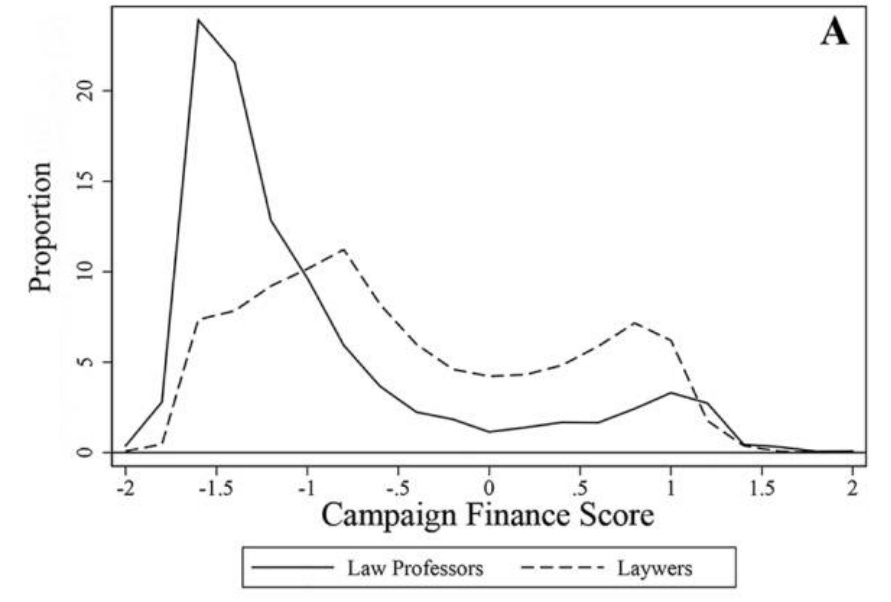

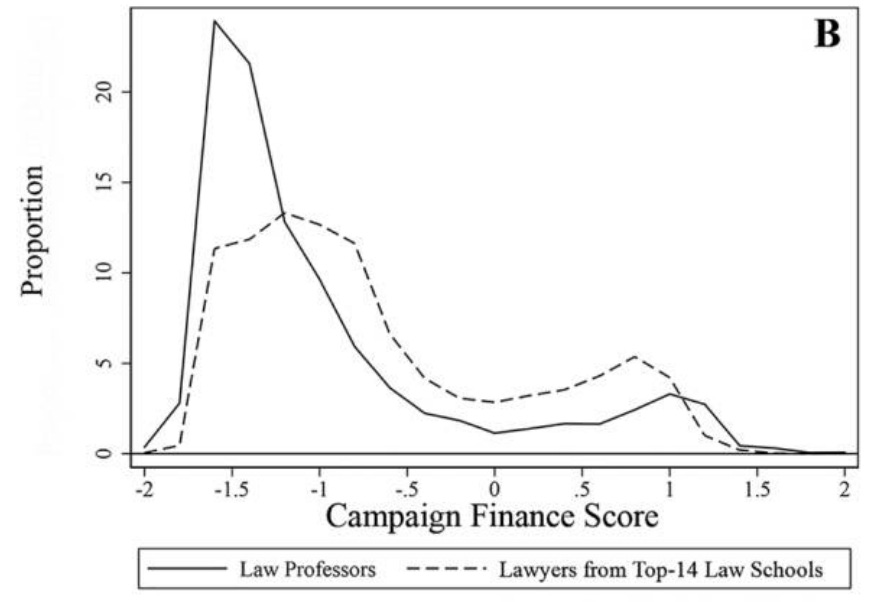

In an article titled “The Legal Academy’s Ideological Uniformity,” published in the Journal of Legal Studies, the researchers found that law professors are not only overwhelmingly liberal, but they are also more liberal than even graduates of the top 14 law schools generally, lawyers working at the largest law firms, former federal law clerks, and federal judges.

The following charts compare the political campaign donations of law professors to various other groups within the legal profession. The extent to which the solid lines skew to the left indicates just how overwhelmingly left are the political ideologies of law professors.

The result of this political orientation monoculture among law professors is that conservative scholars, if they exist at all at a law school, are going to tend to remain silent regarding their support for things opposed by the overwhelmingly left-wing faculty generally. In an article titled “An Empirical Study of Political Bias in Legal Scholarship,” published in the Journal of Legal Studies, the researchers write, in assessing their own findings:

[I]f the dominant ethos in the top law schools is liberal or left-wing, then Republicans are likely to conceal their ideological views in their writings. Republican professors may fear that scholarship that seems conservative will be rejected by left-leaning law review editors and disparaged or ignored by their colleagues, which would damage their chances for promotions, research money, and lateral appointments … Republicans could suppress their ideological views by avoiding controversial topics, taking refuge in fields that have little ideological valence, focusing on empirical or analytical work, or simply writing things that they do not believe.

This extreme ideological bias was demonstrated in spades at the House Homeland Security Committee’s impeachment hearings regarding the Secretary of Homeland Security. At those hearings, the Democrats on the committee invited two law professor witnesses to testify on (no surprise here) why Secretary Mayorkas should not be impeached. But even so, the Democrats could not find a single law professor witness whose views on impeachment weren’t glaringly ideologically biased, and whose hypocrisy was not easily exposed.

The minority invited a law professor, Frank O. Bowman, III, to the Committee on Homeland Security’s January 10, 2024 hearing entitled “Havoc in the Heartland: How Secretary Mayorkas’ Failed Leadership Has Impacted the States,” which addressed the question of Secretary Mayorkas’ impeachment. Putting the understanding of the Framers of the Constitution aside and looking only at the writings of Professor Bowman, it’s striking that in his written testimony he stated that impeachment “should not be attempted based on simple policy disagreements between Congress and the executive branch.” However, while President Donald Trump was president, Professor Bowman wrote a book on impeachment entitled “High Crimes and Misdemeanors: A History of Impeachment for the Age of Trump.” In it, he wrote that the power of the House to impeach cabinet secretaries “remains important … as a signal of legislative displeasure with administration personnel and policy.” So he said one thing in a book about impeaching Republicans, and then said exactly the opposite when the subject was the impeachment of a Democrat.

Professor Deborah Pearlstein was the other minority-invited witness for the January 18, 2024 committee hearing on “Voices for the Victims: The Heartbreaking Reality of the Mayorkas Border Crisis,” and she of course testified in opposition to impeaching a Democrat, offering an extremely narrow view of impeachment. But during the first Trump impeachment, Professor Pearlstein summed up impeachment standards much more broadly. On a New York public radio podcast, she was asked what she took away from a congressional hearing on impeachment standards in 2019. She responded as follows, stating impeachable offenses include such broad charges as “serious offenses against the public trust,” “abuse of authority,” and “abuse of power”:

There, the professors were reasonably uniform in recognizing that it doesn’t have to be a crime, that is to say an impeachable offense doesn’t have to be a crime as currently embodied in the federal criminal code as enacted by Congress. The existing criminal laws didn’t exist when the Framers wrote the Constitution and indeed crimes as such weren’t what the Framers had in mind when they put impeachment into the Constitution. What they were thinking about with the impeachment remedy were serious offenses against the public trust, that is certain things that only the President and other senior officials could do that abused their authority. That is, the idea of abuse of power is sort of the definition of an impeachable offense … They are betrayals of the public trust; they are betrayals of the national interest and that is exactly what the facts underlying the Articles of Impeachment allege here.

Today, “betrayal of the national interest … is exactly what the facts underlying the Articles of Impeachment allege” in the case of Secretary Mayorkas as well.

Professor Pearlstein also wrote the following in a blog post on June 8, 2017:

[I]mpeachment is in the main a political remedy, committed to the discretion of a majority of the House and two-thirds of the members of the Senate, none of whom is bound in any formal (or even informal stare-decisis sort of way) by decisions past legislatures have made in past cases of impeachment.

And Professor Pearlstein also gave testimony to the House Rules Committee on March 3, 2020, in which she, too, like Professor Bowman, stated her view then that Congress can use impeachment as a means of “expressing non-acquiescence with Executive Branch actions.” In that same testimony to the House Rules Committee, Professor Pearlstein wrote:

[I]t has been decades since Congress has effectively asserted its “ambition” to guard against the staggering accretion of power in the presidency … Congress has acquiesced to broad presidential assertions of authority to act without congressional authorization … Congress has allowed its own vast reserves of constitutional authority to address pressing national problems to go unused … Congress’s non-acquiescence – either through subsequent legislation or other express condemnation-– can change the constitutional calculus substantially … [T]he President’s power … is “at its lowest ebb” when the President takes steps “incompatible with the expressed or implied will of Congress.”

As described in the previous essay, precisely the same can be said here, regarding the impeachment of Secretary Mayorkas: Congress has now been left with only one viable means of expressing condemnation of the executive branch’s failing to act in the face of the expressed will of Congress to statutorily mandate illegal alien detention as an enforcement priority -- and that condemnation, as Professor Pearlstein noted in her previous testimony, includes impeachment.

The situation is so bad that the public has long since taken notice of higher educational institutions’ and elite law schools’ overwhelmingly left-wing bias. A Gallup poll from 2023 shows that only 36 percent of respondents expressed having “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education. And that’s not a partisan opinion. Universities have lost the confidence of Americans who identify as Democrats and independents as well. In 2023, universities had the confidence of only 59 percent of Democrats and around just one-third of independents. Universities and law schools have become echo chambers for Democratic Party talking points. But at least the large majority of Americans appear to see through it.