The First Impeachment of a Sitting Cabinet Secretary

What you didn’t read in the media regarding the impeachment of the Secretary of Homeland Security.

As I mentioned a few months ago, I cut back on my Big Picture Substack posting while I worked on another short-term project. Now that the project’s over, I’ll explain here what it was and introduce a new essay series on the topic.

In late December, 2023, I was asked to be a Special Counsel to the House of Representatives’ Committee on Homeland Security to advise the committee on the potential impeachment of Alejandro Mayorkas, the Secretary of Homeland Security. I did so, and greatly enjoyed working with a great chairman and staff while educating myself on the crisis at the Southern Border and the conduct of the person in charge of enforcing border security. The opportunity came about because, back in October, 2023, an impeachment resolution was brought directly to the House floor without having gone through the committee process. The House Democrats offered an amendment to send it to committee, but, in an apparent error, the amendment (which passed with the unanimous support of all the Democrats voting) sent the impeachment to the House Committee on Homeland Security, instead of to the House Judiciary Committee, which is the committee that has traditionally dealt with impeachments regardless of subject matter. Since the House Committee on Homeland Security had no institutional knowledge of the constitutional precedents and history surrounding impeachment, they brought me on board for a stint with them.

The House ultimately impeached the Secretary, but the Senate subsequently voted, on a partisan basis, to adjourn the Senate impeachment trial without hearing any evidence at all. (And if any Senators had relied on the media’s discussion of the subject, they wouldn’t have heard any of the evidence there either.)

During my time working on the impeachment issue, it was great to renew connections with many people I’d worked with over my two decades serving as counsel to the House Judiciary Committee and the House Oversight Committee. It was also a great refresher on media bias (a subject I will likely turn to in a future essay series), as the vast majority of the media reporting on the issue failed to mention any of the relevant facts and law related to the impeachment of the first sitting cabinet secretary ever. I personally spoke with many reporters and relayed to them the core of the following information. The smallest handful of them reported any of it. I spoke individually and at length with reporters from CNN and the Associated Press about the information I'll present here, but none of them reported any of the essential details and context.

A comprehensive review of the evidence is contained in the House Homeland Security Committee’s impeachment report, but here, in this series of essays, I’ll summarize (and footnote) the “big picture” regarding the impeachment of Secretary Mayorkas and, later, the subject of immigration generally.

What follows is the “inside story” of the Mayorkas impeachment — which is only an “inside story” because the media failed to report it.

National borders mark more than geographic limits. As an essayist has written, “[W]hat is a border ..? It is never simply a line, a marker, a wall, an edge. First, it is an idea.”[1] And every nation with borders defined by law is based on some principle underlying that law. An essential part of the American idea is its emphasis on the importance of the impartial rule of law, as ultimately embodied in the world’s oldest written Constitution.

In 1783, George Washington, in a letter to members of the Volunteer Association of Ireland, wrote:

The bosom of America is open to receive not only the Opulent and respectable Stranger, but the oppressed and persecuted of all Nations and Religions; whom we shall welcome to a participation of all our rights and privileges, if by decency and propriety of conduct they appear to merit the enjoyment.[2]

Indeed, America’s first naturalization law required that a person seeking naturalization “mak[e] proof to the satisfaction of [a] Court that he is a person of good character, and tak[e] the oath or affirmation prescribed by law to support the Constitution of the United States.”[3] James Madison, in a speech in the first Congress of 1790 expressing support for the provisions of the first naturalization statute, said “They should induce the worthy of mankind to come,” but that it was “necessary to guard against abuses.”[4]

Those documents testify to an original understanding that America welcomes people of all origins and ethnicities who demonstrate respect for the Constitution of the United States and the rule of law. Indeed, under the Constitution, as the Supreme Court has made clear, “the formulation of [immigration] policies is entrusted exclusively to Congress” and that understanding “has become about as firmly imbedded in the legislative and judicial tissues of our body politic as any aspect of our government.”[5]

When citizens freely join together in a government in which laws are made by duly elected Representatives of the people, the Constitution requires that those laws be followed, and that the terms of the national contract defining rules of membership in the American body politic be adhered to -- both by the people themselves and by the government officials charged with enforcing the immigration laws. As Gouverneur Morris observed at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, “every society from a great nation down to a club ha[s] the right of declaring the conditions on which new members should be admitted.”[6] Our border and immigration laws are those conditions, and the congressional statutes that define who can and cannot legally be in America largely define America itself. And when a federal official orders his staff to violate those laws, he’s committed an impeachable offense.

The Framers clearly understood Congress’s power to impeach and remove applied to high executive branch officials. As Harvard professor Raoul Berger wrote in his seminal book on impeachment:

[I]n the impeachment debate the Convention was almost exclusively concerned with the President … But the Founders were also fearful of the ministers and favorites whom Kings had refused to remove, and they dwelt repeatedly on the need of power to oust corrupt or oppressive ministers whom the President might seek to shelter … The Founders’ concern with removal of “favorites” emerges most clearly in the First Congress. [James] Madison stated: “It is very possible that an officer who may not incur the displeasure of the President may be guilty of actions that ought to forfeit his place. The power of this House may reach him by means of an impeachment, and he may be removed even against the will of the President.” … Abraham Baldwin, also a Framer, put the matter more sharply: a “bad man” “can be got out in spite of the President. We can impeach him and drag him from his place.” “It is this clause,” said Elias Boudinot, “which guards the rights of the House, and enables them to pull down an improper officer, although he should be supported by all the power of the Executive.” Similar remarks were made by Egbert Benson, Samuel Livermore, John Lawrence, and Benjamin Goodhue.[7]

To illustrate that point, after James Madison, the main architect of our Constitution, was elected to the House of Representatives to serve in the first Congress, a bill was proposed to create a Department of Foreign Affairs (now the State Department). When concerns were raised that if Congress created such a department, it could be filled by people who abused the public trust, Madison pointed to a solution in that regard. He said on the House floor “if an unworthy man be continued in office by an unworthy president, the house of representatives can at any time impeach him, and the senate can remove him, whether the president chooses or not.”[8]

Regarding the standard for impeachment that resulted from the Constitutional Convention, when the first proposal was made to add an impeachment power, it was immediately met with calls to enlarge the power to include any offenses against the security of the nation committed by high officials that could not be reduced to the elements of statutory criminal codes, as criminal codes were geared toward private wrongdoing rather than violations of the public trust. As the historians Peter Charles Hoffer and N.E.H. Hull summarize the actions of the delegates, “Through the early debates, every speaker referred to … neglect of duty, and misconduct in office as the only impeachable offenses.”[9] And after Madison objected to the initial vagueness of the proposed impeachment clause, George Mason then moved to add “high crimes and misdemeanors,”[10] a term with a more well-defined meaning in English history:

This passed, 8 to 3, and became the orthodox phraseology … The vote in favor of the compromise motion suggests that the delegates understood that the new terms included … neglect of duty … The addition of misdemeanors to the list of offenses meant that the House of Representatives was permitted to charge officials with … misuse of power, and neglect of duty ...[11]

Regarding the Constitution’s use of the phrase “misdemeanors,” there is sometimes confusion as to whether that term connotes a form of crime. It does not. As Professor Michael Stokes Paulsen has written:

Specifically, the term “misdemeanors,” in its original meaning, carried with it less the sense of a smaller or less serious criminal-law offense (which would be today’s common usage of the word) and more the broader sense of misconduct or misbehavior -- literally of not demeaning oneself properly (“misdemeaning”) in the exercise of an official capacity or position. The breadth of the constitutional language employed as the standard for impeachment thus plainly embraces a range of congressional judgment, extending beyond bare criminality, as to what types of culpable official misconduct so amount to a betrayal of trust, responsibility, duty, or integrity as to warrant removal from office.[12]

Justice Joseph Story paraphrased English impeachment precedents under the same “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” standard in his Commentaries on the Constitution when describing the proper application of the Constitution’s Impeachment Clause, writing that “lord chancellors … and other magistrates have not only been impeached for … acting grossly contrary to the duties of their office, but … for attempts to subvert the fundamental laws, and introduce arbitrary power. So where … a lord admiral to have neglected the safeguard of the sea ..; these have all been deemed impeachable offenses.”[13]

In advocating for the ratification of the Constitution, and its Impeachment Clause, in Federalist Paper Number 65, Alexander Hamilton wrote, “The subjects of [impeachment] are those offenses which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust … [T]hey relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.” He continued that impeachment was “designed as a method of NATIONAL INQUEST into the conduct of public men” and that “the true light in which” the practice of impeachments “ought to be regarded” is “as a bridle in the hands of the legislative body upon the executive servants of the government.”

All of this constitutional history and precedent is at the core of Secretary Mayorkas’s impeachment, and it occurs in a unique historical context.

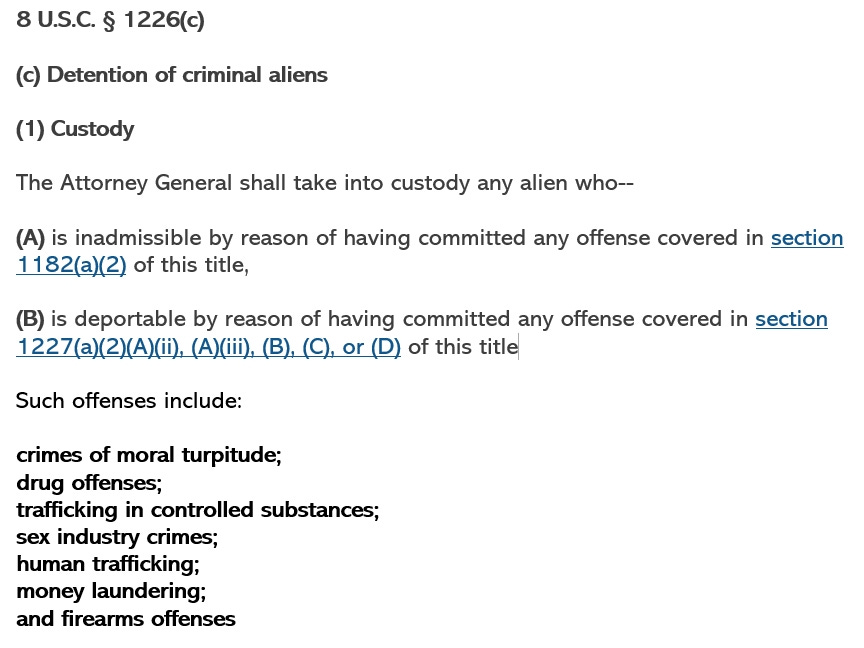

First, federal immigration laws are unique in that they contain mandatory language requiring that immigration enforcement agents “shall take into custody” certain illegal aliens, reflecting the importance Congress placed on these provisions when enacted. These statutes require detention, for example, whenever an enforcement agent comes across an illegal alien with a criminal history of aggravated felonies, including crimes of moral turpitude; drug offenses; trafficking in controlled substances; sex industry crimes; human trafficking; money laundering; and firearms offenses.[14]

Despite the clear statutory text of the federal law requiring the detention of certain criminal aliens, Secretary Mayorkas, on September 30, 2021, issued binding instructions regarding immigration law enforcement to all Department of Homeland Security staff, ordering that, “Our personnel should not rely on the fact of conviction or the result of a database search alone”[15] when evaluating illegal entrants. In doing so, Secretary Mayorkas literally ordered all DHS employees to violate the law, ordering them not to detain aliens when they were discovered to have the same criminal convictions covered by the mandatory detention statute.

Secretary Mayorkas knew his order directed all DHS staff to violate the law because, in the past, he clearly stated that “the requirements of mandatory detention” are not a matter of prosecutorial discretion, but rather obligations on the part of the Secretary of Homeland Security. On May 28, 2014, Alejandro Mayorkas, then serving as Deputy Secretary of DHS, sent a letter to Bob Goodlatte, Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, responding to a letter of Mr. Goodlatte’s. In the letter, Deputy Secretary Mayorkas stated “ICE’s detention and release determinations are made either as a matter of discretion or as a matter of controlling law. Absent the requirements of mandatory detention, a determination to detain or release an alien during the pendency of removal proceedings is based on the discretionary considerations of whether the alien poses a danger to persons or property and whether he or she poses a flight risk.”

The state of Texas challenged Secretary Mayorkas’ September 30, 2021 order in court, and the district court hearing the case held that Secretary Mayorkas’s order, contrary to the statute, “states, DHS ‘personnel should not rely on the fact of conviction …’ when deciding to enforce the law.”[16] As the district court summarized, under Secretary Mayorkas’s order:

[A]n officer cannot rely on the fact of conviction [to detain]. Yet that is precisely what [8 U.S.C.] Section 1226(c) demands: the mandatory detention of certain criminal aliens who are convicted of certain crimes. The [Secretary’s order] says otherwise; staff can no longer follow the statute’s categorical command. This flips the presumption of detention on its head by starting from the premise than an official should not enforce the law.[17]

The district court found that Mayorkas’s orders to violate federal law were binding on DHS personnel, stating in summary that:

The Final Memorandum is final agency action. First, the Final Memorandum is facially binding on DHS personnel. Second, the Considerations Memorandum and other related evidence of DHS’s internal practices demonstrate that the Final Memorandum is being applied in a way that makes it binding. Third, detention data also demonstrate that the Final Memorandum is being applied in a way that makes it binding. Finally, the Final Memorandum creates legal rights for aliens subject to enforcement action.[18]

Indeed, the district court used this chart in its decision to show the dramatic decline in detentions of criminal aliens following Secretary Mayorkas’s order:

On appeal by the Biden Administration, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with the district court, concluding that:

[T]he [DHS] Memo compels officials to comply … in a manner that violates statutory law. For example, it provides that the guidelines “are essential to advancing this Administration's stated commitment to advancing equity for all, including people of color and others who have been historically underserved, marginalized, and adversely affected by persistent poverty and inequality.” DHS's replacement of Congress's statutory mandates with concerns of equity and race is extralegal, considering that such policy concerns are plainly outside the bounds of the power conferred by the INA [Immigration and Nationality Act].[19]

The second reason this impeachment is historically unique involves the ramifications of the Supreme Court’s decision (or rather, its non-decision) in this case. The Supreme Court, in United States v. Texas,[20] agreed to hear the Biden Administration’s appeal of the case in which every lower court had concluded Secretary Mayorkas ordered his staff to violate the criminal alien mandatory detention statute, which resulted in massive injuries to the states and their citizens. As the concurring Justices in the case noted, “The States proved that the [Secretary’s] Guidelines increase the number of aliens with criminal convictions and final orders of removal released into the States. They also proved that, as a result, they spend more money on everything from law enforcement to healthcare.”[21]

But despite that, the majority of the Court, in an opinion written by Justice Kavanaugh, dismissed the case on standing grounds, essentially deciding not to decide the merits of the case. The majority concluded “We take no position on whether the Executive Branch here is complying with its legal obligations under [federal statutory law]. We hold only that the federal courts are not the proper forum to resolve this dispute.”[22]

So what then is the proper forum to resolve this dispute? The majority explains that “even though the federal courts lack … jurisdiction over this suit, other forums remain open for examining the Executive Branch’s arrest policies. For example, Congress possesses an array of tools to analyze and influence those policies [and] those are political checks for the political process.”[23]

And just what do these “political checks” include? That subject was discussed during the oral argument in the case, when Justices ask blunt questions to litigants in order to get a fuller sense of what the ramifications of their decision might be. These oral arguments often reveal deeper understandings of the issues involved in a case. And during the oral argument in United States v. Texas, Justice Kavanaugh, who went on to write the majority opinion, made a remarkable statement about the position of the United States Solicitor General.[24] During the oral argument, Justice Kavanaugh explicitly said that he understood the Solicitor General’s position to be that Congress would be “forced” to impeach Secretary Mayorkas. Justice Kavanaugh, speaking to the Solicitor General, said:

I think your position is, instead of judicial review, Congress has to resort to shutting down the government or impeachment or dramatic steps if it -- if some administration comes in and says we're not going to enforce laws or at least not going to enforce the laws to the degree that Congress by law has said the laws should be enforced, and -- and that's forcing -- I mean, I understand your position, but it's forcing Congress to take dramatic steps, I think.[25]

The Solicitor General replied “Well, I think that if those dramatic steps would be warranted, it would be in the face of a dramatic abdication of statutory responsibility by the executive.”[26] To which we must all ask, what more dramatic abdication of statutory authority could there be than ordering all DHS employees to violate a federal law requiring the detention of criminal aliens?

Justice Kavanaugh and the majority of the Court went on the deny the States, and anyone else, judicial review of precisely the sort of legal violations at issue here, leaving Secretary Mayorkas’s orders to violate the law in place — unless he was impeached by the House and removed from office by the Senate, to be replaced by someone willing to perform the duties of office and comply with the law.

Impeachment was the only viable option for relief for the States, as no other alternatives were feasible. While the majority opinion in United States v. Texas went on to state “Congress possesses an array of tools to analyze and influence those policies -- oversight, appropriations, the legislative process, and Senate confirmations, to name a few,”[27] none of those particular “political tools” (other than impeachment and removal) were viable solutions in this case:

Oversight. The House Committee on Homeland Security had conducted extensive oversight on this matter, and as a result it was clear that Secretary Mayorkas is not enforcing and will not enforce certain provisions of the federal immigration laws.

Appropriations. If Congress appropriated more money to the Department of Homeland Security to enforce the law as written, that money would be wasted, since the Secretary has clearly demonstrated he will not enforce the federal immigration laws as written. If Congress appropriated less money, the Secretary would then have had the excuse — which he did not otherwise have — that the Department is underfunded, and therefore cannot enforce the law as written.

Senate confirmations. The Senate cannot confirm a new Secretary until the old one has vacated the position. And that is exactly what the House of Representatives was forced to do through the impeachment process.

The legislative process. To what end could the House of Representatives use the legislative process when the Secretary has clearly demonstrated he will order his staff to violate provisions of federal immigration laws as written in statutes already enacted? There’s no point negotiating carefully balanced new federal legislation when the Secretary now has a blank check to unilaterally order the violation of any and every negotiated provision. Resulting legislation could contain strict, mandatory border enforcement provisions – and Secretary Mayorkas could order they all be violated, without judicial review.

In sum, Secretary Mayorkas ordered all DHS staff to violate the federal statute that requires the detention of criminal aliens with histories of aggravated felonies. The lower courts so held, but when the Supreme Court accepted the case, it held that no court could decide the issue one way or the other, as it was most appropriately decided by Congress through its unique powers, including its power of impeachment and removal of high executive branch officials. Indeed, the author of the majority opinion understood it was the Solicitor General’s own position that in the event judicial review was denied to the States, impeachment would be forced upon Congress, as oversight, appropriations, and legislation would change nothing under a Secretary who has willfully and systemically refused to comply with federal immigration laws. Impeachment and removal by Congress was left as the only viable option for providing relief to the States and their citizens.

To that end, the Founders understood the unique role of the Senate in defending the interests of the States, and the States have now been denied judicial review of Secretary Mayorkas’s unconstitutional immigration policies, under which the citizens of every state have suffered, and will continue to suffer. Although Senators are no longer directly elected by state legislatures, they run in statewide elections, and they continue to have a unique duty to protect the interests of the States they represent. Senators who voted to prevent the presentation of any evidence regarding Secretary Mayorkas’s impeachable conduct during a Senate impeachment trial failed in that unique duty.

In Federalist Paper No. 62, James Madison said Senators have a special obligation, a “senatorial trust,”[28] such that the Senators embody a “constitutional recognition of the portion of sovereignty remaining in the individual states” and should act to preserve that sovereignty.[29] In Federalist Paper No. 45, Madison wrote that “The Senate … will owe its existence more or less to the favor of the State Governments,”[30] and would be “disinclined to invade the rights of the individual States, or the prerogatives of their governments.”[31]

In Federalist Paper No. 59, Alexander Hamilton also emphasized that Senators secured “a place in the organization of the National Government” for the “States, in their political capacities.”[32] During the ratification convention in New York, Hamilton said further that “you will certainly see that the senators will constantly look up to the state governments with an eye of dependence and affection. If they are ambitious to continue in office, they will make every prudent arrangement for this purpose, and, whatever may be their private sentiments or politics, they will be convinced that the surest means of obtaining a reelection will be a uniform attachment to the interests of their several states.”[33] Hamilton then told the convention delegates “the senators will constantly be attended with a reflection, that their future existence is absolutely in the power of the states. Will not this form a powerful check?”[34]

Secretary Mayorkas committed an impeachable offense in unconstitutionally and unilaterally creating programs designed to violate federal immigration laws and facilitate illegal entries, in violation of the separation of powers. Indeed, there is a direct analogy here to the impeachment articles against President Richard Nixon. While nowhere in the Nixon impeachment articles is there any reference to a “crime” or “criminal” activity committed by the President himself, Article II of the Nixon impeachment articles refers to Nixon’s acting in ways “not authorized by law” and in ways that constituted “unlawful activities.”[35] And that is exactly what Secretary Mayorkas did in spades: he acted in ways not authorized by law, and beyond that, he created programs, not authorized by Congress, designed to violate the immigration laws. Article I of the Nixon impeachment articles also charged Nixon with “making false and misleading statements” and “false and misleading testimony,” and they concluded he “acted in a manner contrary to his trust as President and subversive of constitutional government, to the great prejudice of the cause of law and justice, and to the manifest injury of the people of the United States.”[36] Indeed, while the Nixon articles of impeachment did not charge Nixon with committing a crime himself, they did charge him with facilitating other people “in their attempts to avoid criminal liability.”[37] In the same way, Secretary Mayorkas’s creation of programs designed to violate the federal immigration laws facilitated the entry of unprecedentedly large numbers of illegal entrants.

So now, you know much more about the Mayorkas impeachment effort than you might have gleaned from the popular press.

In the next essay in this series, we'll explore the unfortunate law school dynamics surrounding law professor opposition to the Mayorkas impeachment.

[1] James Crawford, The Edge of the Plain (2023).

[2] “Washington to Members of the Volunteer Association of Ireland” (December 2, 1783) in Writings of George Washington, John C. Fitzpatrick, ed. (Government Printing Office 1931-44) 27:254. Washington expressed similar sentiments to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1790, writing that “For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens …” George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island (August 18, 1790), in The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 6, 1 July 1790 – 30 November 1790 (ed. Mark A. Mastromarino. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996) at 284–286.

[3] An act to establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization (March 26, 2 1790), in 6 Documentary History of the First Congress 1516 (Charlene B. Bickford et al., eds. John Hopkins University Press 1986).

[4] The Legislative History of Naturalization in the United States (1906 reprint, New York: Arno 1969) at 40, 23.

[5] Galvan v. Press. 347 U.S. 522, 531 (1954).

[6] 2 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (Max Farrand ed., 1937), at 238.

[7] Raoul Berger, Impeachment: The Constitutional Problems (1973) at 100-101 and n.228 (citations omitted) (citing, regarding Madison, The Papers of James Madison, vol. 12, 2 March 1789 – 20 January 1790 and supplement 24 October 1775 – 24 January 1789 (ed. Charles F. Hobson and Robert A. Rutland, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1979) at 170–174).

[8] “Removal Power of the President, [17 June] 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-12-02-0143.

[9] Peter Charles Hoffer and N.E.H. Hull, Impeachment in America: 1635–1805 (Yale University Press 1984), at 101.

[10] Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution provides that “The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

[11] Hoffer and Hull, Impeachment in America: 1635–1805 (Yale University Press 1984), at 101-02.

[12] Michael Stokes Paulsen, “Checking the Court,” 10 N.Y.U. J. L. & Liberty 18, 70-71 (2016) (citing Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) (defining misdemeanor as “offence; ill behavior …”).

[13] Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution (1833) 2: § 798.

[14] See generally 8 U.S.C. §§ 1182(a)(2).

[15] Department of Homeland Security, “Guidelines for the Enforcement of Civil Immigration Law” (September 30. 2021) (signed by Secretary Mayorkas) (emphasis added) at 4, available at https://www.ice.gov/doclib/news/guidelines-civilimmigrationlaw.pdf.

[16] 606 F.Supp. 3d 450, 457 (S.D. Tex. 2022).

[17] Id. at 487 (emphasis added).

[18] Id. at 469.

[19] Texas v. United States, 40 F.4th 205, 226.

[20] 599 U.S. 670 (2023).

[21] Id. at 690 (Gorsuch, J., concurring).

[22] Id. at 685.

[23] Id.

[24] As the Solicitor General’s official website states, “The Solicitor General determines … the positions the government will take before the [Supreme] Court.” About the Office, OFFICE OF THE SOLICITOR GENERAL, U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, https:// www.justice.gov/osg/about-office (last accessed Jan. 29, 2024).

[25] Transcript of Oral Argument at 53, United States v. Texas, 599 U.S. 670 (2023) (No. 22- 58).

[26] Id.

[27] 599 U.S. 670, 685 (2023).

[28] Federalist Paper No. 62.

[29] Id.

[30] Federalist Paper No. 45.

[31] Id.

[32] Federalist Paper No. 59.

[33] 2 The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia in 1787, at 306 (Jonathan Elliot ed., 2d ed., Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott 1888).

[34] Id. at 317-18. The understanding of Senators as unique defenders of the interests of the states predominated after the Constitution was ratified as well. In a July 1789 letter to John Adams, Roger Sherman wrote that “The senators … will be vigilant in supporting their rights against infringement by the … executive of the United States.” The Founders’ Constitution, vol. 2, 232 (Philip B. Kurland & Ralph Lerner eds., 1987). In his 1803 edition of Blackstone's Commentaries, George Tucker wrote that if a senator abuses the confidence of “the individual state which he represents,” he “will be sure to be displaced.” Blackstone’s Commentaries: With Notes of Reference to the Constitution and Laws of the Federal Government of the United States and the Commonwealth of Virginia 23–24 (St. George Tucker ed., Philadelphia, Birch & Snell 1803).

[35] House Judiciary Committee, Articles of Impeachment of Richard Nixon, H.R. Rep. No. 1305, 93rd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1974) at 3–4.

[36] Id. at 2.

[37] Id.

Paul, Well this is something about which I never thought I would learn something from you! Fascinating, educational, depressing in its own way. Aligns with the other ridiculous events of the weekend. I cannot imagine what they threatened Johnson with, but it is all so corrupt the good get sucked in with the (most of them) evil. Scary.