How Christianity Influenced the Development of Individual Rights – Part 3

Seeing individuals as controlling their own will led to government controlling people less.

This is the third and final essay in a three-essay series recounting historian Larry Siedentop’s book Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism, which describes how, long before the Protestant Revolution and the Enlightenment, the core ideas of Christianity developed a governing concept of sovereign individuals with unalienable rights.

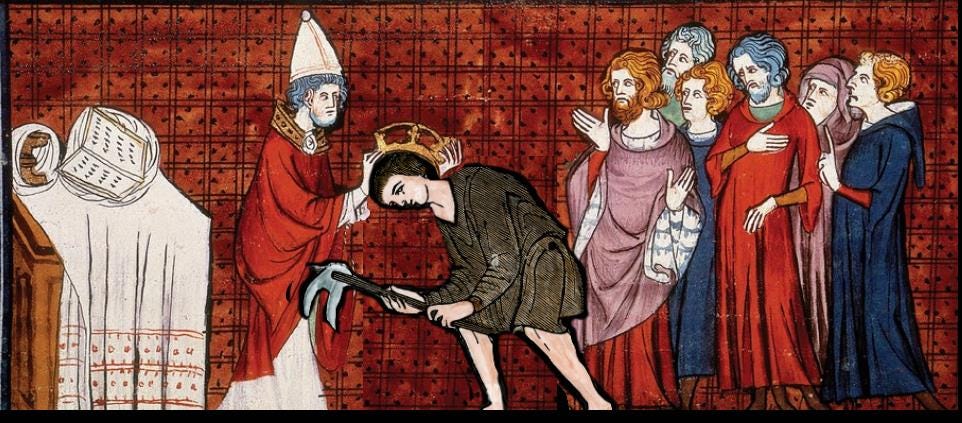

Canon law, the law that developed to govern the internal operations of the Church but which also affected the rights of others subject to the Church’s jurisdiction, came to adopt the principle of individual sovereignty:

There was a deep excitement attached to the creation of canon law. It derived from the need to sift through the rules of Roman law to establish which were compatible with Christian beliefs. As Ivo of Chartres insisted at the end of the eleventh century, only those parts of Roman law acceptable to the church should be adopted … The papacy was the fulcrum of the system canon lawyers were creating. Theirs was an audacious enterprise, for the attempt to invest one agency with a monopoly of final legal authority flew in the face of the habits and attitudes of a feudal society, with its radical decentralization, multiple jurisdictions and emphasis on custom … We can see the impact of this intellectual revolution on thinking about political authority. The canonists were greatly influenced by the notion of imperium in Roman law. Yet their translation of imperium into the papal claim of sovereignty changed its meaning. Individuals rather than established social categories or classes became the focus of legal jurisdiction. Individuals or “souls” provided the underlying unit of subjection in the eyes of the church, the unit that counted for more than anything else. In effect, canon lawyers purged Roman law of hierarchical assumptions surviving from the social structure of the ancient world. This shift away from the assumptions of the ancient world gave birth to the idea of sovereignty. By making the individual the unit of legal subjection – through the stipulation of “equal subjection”– the papal claim of sovereignty prepared the way for the emergence of the state as a distinctive form of government. But if we look closely, the papal claim introduced equality both as a foundation and as a consequence. While “equal subjection” is a necessary condition for the state and sovereignty, moral equality also provides the basis for limiting the power of the state and its sovereign authority. The intellectual sword raised by the papacy was thus two-edged.

Canon law judges were instructed to apply the Golden Rule to themselves and put themselves in the place of those they were judging:

A late eleventh-century tract, Concerning True and False Penance, prescribes the proper attitudes for a judge. The judge must take the golden rule seriously, and put himself in the place of the person being examined, for attempting to understand a person’s motives is also the best way of taking account of the context of action, inducing humility as well as understanding: “For one who judges another … condemns himself. Let him therefore know himself and purge himself of what he sees offends others ... Let him who is without sin cast the first stone (John 8.7) ... for no one is without sin in that all have been guilty of crime. Let the spiritual [that is, ecclesiastical] judge beware lest he fail to fortify himself with knowledge and thereby commit the crime of injustice. It is fitting that he should know to recognize what he is to judge.”

And the law developed to increasingly recognize the sovereignty of individuals in making binding agreements:

The concern of canon lawyers to identify and protect the role of intentions is striking. That concern is the key to a host of legal developments in the twelfth century: “In marriage law, by the end of the twelfth century, the simple consent of two parties, without any formalities, could constitute a valid, sacramental marriage. In contract law, a mere promise could create a binding obligation – it was the intention of the promisor that counted … Feudal magnates who looked on their wards merely as valuable property to be disposed of, came up against the church’s insistence on consent. And in the case of the rules governing inheritance, an overriding concern in Germanic custom and Roman law to perpetuate the family as a unit was modified to respect the individual testator’s wishes, for the “protection of his soul.” As a consequence, the “testament” became a “will,” a term evoking the individual.

And the focus on intentionality sowed the seeds of the modern law of negligence:

In criminal law, the degree of guilt and punishment was again related to the intention of the individual defendant, and this led, as in modern legal systems, to complex considerations about negligence and diminished responsibility.

And even corporate law developed to allow individuals, not higher authorities, to create corporations, and to allow those corporations to control their own assets:

[F]undamental changes in corporation law were introduced by the canonists, changes in the principles that had governed corporations in Justinian’s Corpus Juris Civilis. Yet simply noticing these changes is not enough. What was their source? These changes followed directly from substituting the belief in moral equality for the ancient belief in natural inequality. That substitution generated the four changes. First, canonists rejected the view that only associations recognized by public authority could possess “the privileges and liberties of corporations.” In canon law, by contrast, any group of persons organizing themselves to pursue a shared goal – whether as a guild, hospital or university – could constitute a legitimate corporation. This model of voluntary association, of association based on the individual will, can be traced back to the way monastic communities had been created. Implicit is the assumption that authority flows upwards rather than from the top down … The reaction to that aristocratic view of the nature of a corporation – as constituted from above – also explains the fourth change made by canonists. They rejected the maxim in Roman law that “what pertains to a corporation does not pertain to its members.” By contrast, canon lawyers took the view that the property of a corporation was the “common property” of its members, with both the advantages and liabilities that entailed for each member; it did not belong to its officers, to dispose of as they saw fit. The overturning of these Roman law maxims provides the clearest possible evidence of the way canon lawyers rejected the aristocratic assumptions underlying Roman law. It reveals how creative they were. At times a majority principle for decision-making seems to be emerging. Canon law was not simply parasitic on Roman law. Canonists promoted an understanding of the corporation as a voluntary association of individuals who remain the source of its authority, rather than as a body constituted by superior authority and wholly dependent on that authority for its identity.

Because individual rights had now come to be associated with divine commands, the concept of “equality” among individuals came to be considered “natural”:

Thanks to the doctrine of papal sovereignty, the connotations of “nature” were changing. Appeals to “nature” were increasingly associated with equality, that is, with the basic claims of individuals. [A statement by the Pope in 1204 read:] “But it may be said, that kings are to be treated differently from others. We, however, know that it is written in the divine law, ‘You shall judge the great as well as the little and there shall be no difference of persons’.”

Debates over the role of reason in the Church gave rise to a format of dialectical-style debate in the newly formed universities that presaged our own “adversary system” in which the truth is considered most likely to arise from a give-and-take debate between two zealous opponents:

Philosophy was emerging out of theology, leading to ever more intense debate about the “proper” relationship between reason and faith. But not only that. The developments in both theology and philosophical argument testified to the presence of a new institution which fostered intellectual ambition and achievement, giving far more reality to talk of “schools of thought” or “traditions” … For in addition to the growth of urban centres and trade during this period – spreading the seeds of a social class intermediate between the feudal aristocracy and serfs – the European university made its appearance. The university was something almost unprecedented. It gave the claims of individual reason and dissent a public space which had previously been lacking … The assembly of minds which the new universities promoted gave a tremendous fillip to argument. The marshalling of arguments “for” and “against”– which had roots in the dialectics championed by Abelard and the methods applied in Gratian’s Decretum – shaped the form of university teaching. “Disputations” were as important as lectures on required texts. In a disputation some proposition had a “defender” who was confronted with an “objector,” while the arguments put forward on both sides were finally arranged and assessed by the presiding professor.

Siedentop summarizes his book as follows:

[T]he argument of this book: that in its basic assumptions, liberal thought is the offspring of Christianity. It emerged as the moral intuitions generated by Christianity were turned against an authoritarian model of the church. The roots of liberalism were firmly established in the arguments of philosophers and canon lawyers by the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries: belief in a fundamental equality of status as the proper basis for a legal system; belief that enforcing moral conduct is a contradiction in terms; a defence of individual liberty, through the assertion of fundamental or “natural” rights; and, finally, the conclusion that only a representative form of government is appropriate for a society resting on the assumption of moral equality … Liberal secularism sought to limit the role of government through a structure of fundamental rights, rights that create and protect a sphere of individual freedom, a private sphere. Religion thus became a matter for the private sphere, a matter of conscience. Liberal secularism sought to protect that private sphere, moreover, by means of constitutional arrangements that would disperse and balance powers in the state. This profound moral and intellectual development did not take place overnight. It emerged by fits and starts over several hundred years. The story of its development – from sixteenth-century natural rights theory, through the writings of Grotius and Hobbes, Locke and Montesquieu, to early nineteenth-century thinkers such as Constant, Tocqueville and J. S. Mill – has often been told. It is a story about what might be called the liberal “moment” in European history … The view that the Renaissance and its aftermath marked the advent of the modern world – the end of the “middle ages”– is mistaken. By the fifteenth century canon lawyers and philosophers had already asserted that “experience” is essentially the experience of individuals, that a range of fundamental rights ought to protect individual agency, that the final authority of any association is to be found in its members, and that the use of reason when understanding processes in the physical world differs radically from normative or a priori reasoning. These are the stuff of modernity … Secularism is Christianity’s gift to the world, ideas and practices which have often been turned against “excesses” of the Christian church itself. What is the crux of secularism? It is that belief in an underlying or moral equality of humans implies that there is a sphere in which each should be free to make his or her own decisions, a sphere of conscience and free action. That belief is summarized in the central value of classical liberalism: the commitment to “equal liberty.” Is this indifference or non-belief? Not at all. It rests on the firm belief that to be human means being a rational and moral agent, a free chooser with responsibility for one’s actions. It puts a premium on conscience rather than the “blind” following of rules. It joins rights with duties to others … Strikingly, in its first centuries Christianity spread by persuasion, not by force of arms – a contrast to the early spread of Islam. When placed against this background, secularism does not mean non-belief or indifference. It is not without moral content. Certainly secularism is not a neutral or “value-free” framework, as the language of contemporary social scientists at times suggests. Rather, secularism identifies the conditions in which authentic beliefs should be formed and defended. It provides the gateway to beliefs properly so called, making it possible to distinguish inner conviction from mere external conformity.

In the next series of essays, we’ll look at various statistics on religion and culture.

“Canon law” not “cannon law”.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canon_law_of_the_Catholic_Church