Happiness – Part 3

Physical and mental health.

Continuing this essay series on happiness, primarily with reference to Wellbeing: Science and Policy, by Richard Layard and Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, and Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness and How Leaders Missed It, by Jon Clifton, the head of the Gallup polling organization, this essay focuses on one of the five main elements of wellbeing: physical and mental health.

As Layard and De Neve write:

What explains this effect of mood upon physical health? The clearest channel is through the effects of stress. The body has a mechanism that responds to stress in a similar way whether the stress is physical or mental. This is sometimes called the “fight or flight” response: our heart rate, blood pressure and breathing rate increase; we sweat more and our mouths go dry. This response begins in the brain, which is linked to the rest of the body by two main sets of nerves. One set includes the sensory nerves and the motor nerves, which give conscious instructions to our limbs about what to do. But the other set is the ‘autonomic nervous system’, which is largely outside our conscious control and regulates the workings of all our internal organs. The autonomic system has two main branches: the sympathetic and the para-sympathetic. It is the sympathetic nervous system that initiates the fight or flight response. It immediately instructs the adrenal gland to produce what Britons call adrenaline and Americans call epinephrine. This is a hormone (Greek for messenger) that enters the bloodstream and galvanises the whole body for action. It also mobilises the immune system to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines in case they are needed to handle possible infections. The parasympathetic nervous system, in contrast, calms the body. When it is active, the body’s organs become less active. For example, in meditation or breathing exercises the vagus nerve is active in reducing the heart rate. At the same time, a second hormone is produced in another part of the adrenal gland: cortisol. A message goes from the brain’s hypothalamus to the pituitary gland to the adrenal gland, which releases cortisol into the bloodstream, and this then stimulates the muscles by releasing their store of glucose. The stress response is totally functional when the stress is brief. But when the stress is persistent, it can lead to over-activity of the immune system (especially of C-reactive protein and IL6) and to persistent inflammation around the body, which eventually reduces life expectancy … In Western countries the most common sources of prolonged stress are psychological, and increased inflammation has been observed as a result of marital conflict, caring for demented relatives, social isolation, social disadvantage and depression … Perhaps the simplest evidence of the effect of mind on body comes from a simple experiment. In it people were given a small experimental wound. Those who were depressed or anxious took the longest to recover. In another experiment, people were given injections, and people in the greatest psychological distress developed the fewest antibodies. Since we can affect the mind by psychological intervention, we can also affect the body that way. For example, mindfulness meditation reduces the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Perhaps the most striking findings regarding happiness and mental states over the past decade or so has been the influence of politics on happiness and well-being, especially in the United States and among young people. As Layard and De Neve write: “Young people tend to be happier than people in middle age and than people at older ages (except in North America and Europe).” As Jonathan Haidt and Zach Rausch have pointed out:

Dartmouth labor economist and adviser to the [United Nations] David Blanchflower has found that the classic “U-shaped curve of well-being” and the “hump-shaped curve of ill-being” [which showed younger and older people being happier in decades past] have recently disappeared [in America] because young adults (18-25) have been doing so much worse since the mid-2010s (especially young women). He has published a series of articles on the topic and has “shown something astonishing and of global importance: the general contour of happiness across the age-span has changed around the world. Young adults are now the least happy people, and this broad multinational change began sometime in the mid-2010s, right as Gen Z was entering this age-group.

Politics is the primary reason. As Layard and De Neve write:

[S]imply look at differences in wellbeing between people who identify as left-wing or right-wing. This task is easy enough to accomplish. Many large-scale datasets used in happiness research including the European Social Survey and Gallup World Poll also contain information on political ideology. The findings of this body of research constitute an impressively large literature. The results are remarkably consistent: conservatives (right-wing) are generally happier than liberals (left-wing). A number of possible explanations have been put forth to explain these gaps. They have included conservatives’ higher levels of perceived personal agency, more transcendent moral beliefs, greater perceptions of the fairness of the world and more positive life-outlooks. Relative to liberals, conservatives are also generally less likely to be unemployed, more satisfied with their finances and more likely to own homes.

As Haidt elaborates:

In September 2020, Zach Goldberg, who was then a graduate student at Georgia State University, discovered something interesting in a dataset made public by Pew Research. Pew surveyed about 12,000 people in March 2020, during the first month of the Covid shutdowns. The survey included this item: “Has a doctor or other healthcare provider EVER told you that you have a mental health condition?” Goldberg graphed the percentage of respondents who said “yes” to that item as a function of their self-placement on the liberal-conservative 5-point scale and found that white liberals were much more likely to say yes than white moderates and conservatives. (His analyses for non-white groups generally found small or inconsistent relationships with politics.) I wrote to Goldberg and asked him to redo it for men and women separately, and for young vs. old separately. He did, and he found that the relationship to politics was much stronger for young (white) women. You can see Goldberg’s graph here, but I find it hard to interpret a three-way interaction using bar charts, so I downloaded the Pew dataset and created line graphs, which make it easier to interpret. Here’s the same data, showing three main effects: gender (women higher), age (youngest groups higher), and politics (liberals higher). The graphs also show three two-way interactions (young women higher, liberal women higher, young liberals higher). And there’s an important three-way interaction: it is the young liberal women who are highest. They are so high that a majority of them said yes, they had been told that they have a mental health condition.

Figure 1. Data from Pew Research, American Trends Panel Wave 64. The survey was fielded March 19-24, 2020. Graphed by Jon Haidt.

Epidemiologist Catherine Gimbrone and her coauthors compared depressive attitudes of 12th-graders from 2005 to 2018 between those ideologically aligned with conservatism (defined in the study as support of individual liberty) and liberals. The research found that “conservatives reported lower average depressive affect, self-derogation, and loneliness scores and higher self-esteem scores than all other groups.”

As reported in Psychology Today, researchers found that:

People with left-wing economic-political beliefs had higher rates of anxiety disorder symptoms. Results showed that higher overall anxiety symptoms at age 44 predicted concerns about inequality and the environment, distrust in politics, and lower work ethic at age 50. Similarly, concerns about inequality and the environment at ages 33 and 42 predicted higher overall anxiety symptoms at age 44. Regarding more specific disorders, symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder and phobia, but not panic disorder, at age 44 predicted higher concerns about inequality and the environment at age 50. Additionally, phobia symptoms predicted greater distrust in politics and lower work ethic at age 50. Similarly, concern about inequality at ages 33 and 42 predicted generalized anxiety disorder, panic (although this was significant at 42 only), and phobia at age 44. The importance of family values had a less consistent effect: people with lower importance of family values at age 42 had higher overall anxiety and generalized anxiety disorder symptoms at age 44 only. In summary, having an anxiety disorder was associated with some political views but not others. Specifically, over the long term, anxiety disorders symptoms were most consistently associated with higher concerns about inequality in particular and to a lesser extent with the environment, as well as political distrust and with having a lower work ethic. These views were more often associated with generalized anxiety disorder and phobia rather than panic disorder.

A large study published in 2019, involving five different data samples from 16 Western countries spanning more than four decades, found that “In sum, conservatives reported greater meaning in life and greater life satisfaction than liberals,” a robust and consistent finding in the 16 distinct countries examined. It was generally truer for social conservatives than fiscal conservatives, and the greater-meaning-in-life “slope spiked upward among individuals who were very conservative.” This was true for conservatives “at all reporting periods (global, daily, and momentary).” Conservatives experience greater meaning in life across their lives generally, but also daily and at most given moments throughout the day. The researchers conclude these findings are “robust” and that “there is some unique aspect of political conservativism that provides people with meaning and purpose in life.”

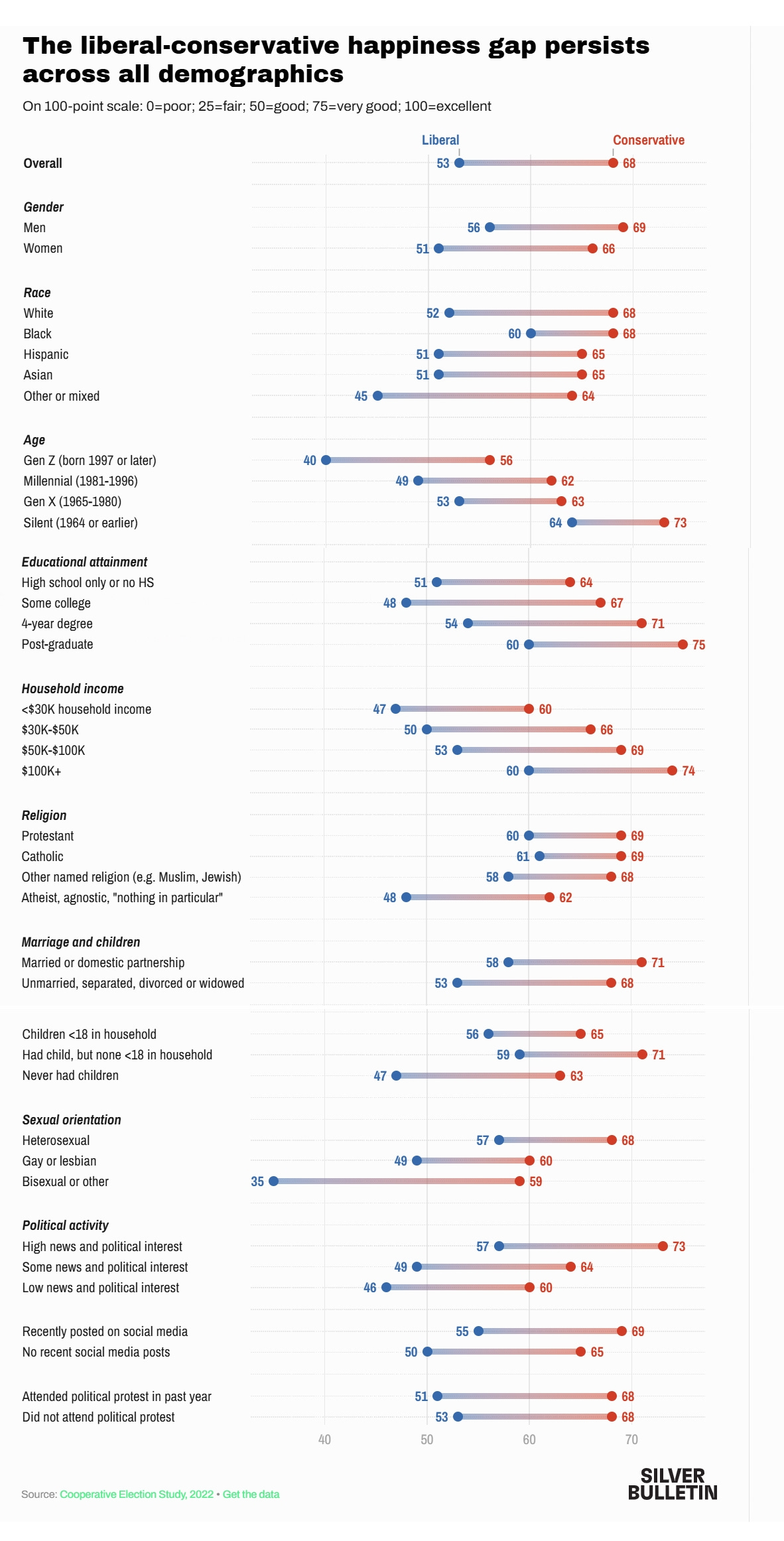

As Nate Silver writes, using the following graph, “the liberal-conservative [happiness] gap is fairly consistent across all of these characteristics”:

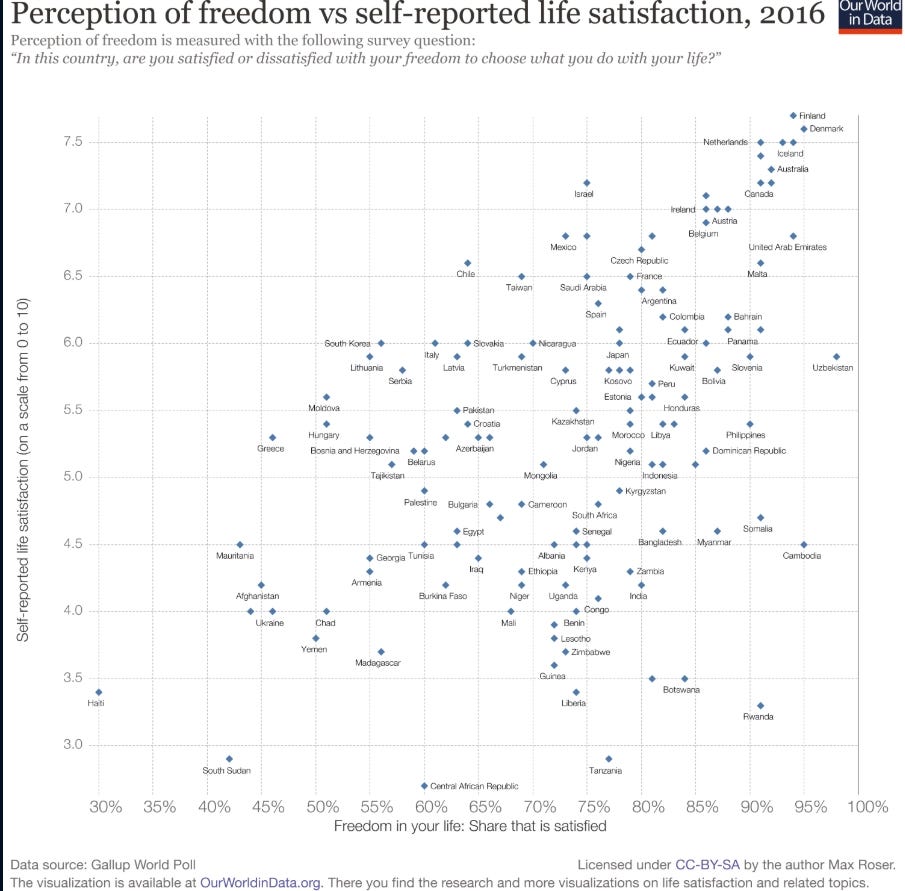

As Our World in Data reports, those with a greater sense of freedom and a greater sense of control over their own lives (that is, those with an internal locus of control) tend to be happier:

A particular channel through which social environment may affect happiness is freedom: the society we live in may crucially affect the availability of options that we have to shape our own life. This visualization shows the relationship between self-reported sense of freedom and self-reported life satisfaction using data from the Gallup World Poll. The variable measuring life satisfaction corresponds to country-level averages of survey responses to the Cantril Ladder question (a 0-10 scale, where 10 is the highest level of life satisfaction), while the variable measuring freedom corresponds to the share of people who agree with the statement “In this country, I am satisfied with my freedom to choose what I do with my life.” As we can see, there is a clear positive relationship: countries, where people feel free to choose and control their lives, tend to be countries where people are happier. As Inglehart et al. (2008) show this positive relationship holds even after we control for other factors, such as income and strength of religiosity.

Researchers have also found that depression hurts people’s long-term prospects, as it leads to fewer hours worked, and therefore to the accumulation of less human capital that would otherwise be derived from the work experience itself. Those researchers write:

In this study, we examine how an episode of depression experienced in early adulthood affects subsequent labor market outcomes. We find that, at age 50, people who had met diagnostic criteria for depression when surveyed at ages 27-35 earn 10% lower hourly wages (conditional on occupation) and work 120-180 fewer hours annually, together generating 24% lower annual wage incomes. A portion of this income penalty (21-39%) occurs because depression is often a chronic condition, recurring later in life. But a substantial share (25-55%) occurs because depression in early adulthood disrupts human capital accumulation, by reducing work experience and by influencing selection into occupations with skill distributions that offer lower potential for wage growth. These lingering effects of early depression reinforce the importance of early and multifaceted intervention to address depression and its follow-on effects in the workplace.

And young liberal women, especially unmarried women, are the unhappiest of all. According to Gallup:

In 2001-2007, young women’s views were closer to those of liberals aged 30+ than conservatives 30+ on 63% of the issues reviewed. This increased to 78% in 2008-2016 and 87% in 2017-2024. Separately, the analysis shows that young women’s views also moved closer to liberals and further from moderates, with their more-liberal-than-moderate responses rising from 33% in the Bush era to 55% in the Trump/Biden era. The same analysis applied to young men shows far less change in their ideological proximity to older liberals, moderates or conservatives than is true for young women. In 2001-2007, young men’s views aligned with liberals aged 30+ more than conservatives 30+ on 47% of the issues reviewed. This increased to 57% in 2008-2016 before sliding back to 50% in 2017-2024. In other words, on the whole, young men’s views have been slightly more liberal in the Trump/Biden period than they were in the Bush era, but less liberal than during the Obama era. This echoes young men’s lesser likelihood of self-identifying as politically liberal between 2017 and 2024 (25%) than between 2008 and 2016 (27%).

Interestingly, popular music, which tends to appeal to younger people, also appears to have gotten sadder and angrier over the years.

As Tyler Cowen writes, summarizing other research:

Adding marital status to the mix, the [Republican] advantage among married men shoots up to 20 points (59% Republican to 39% Democrat) and shrinks among unmarried men to just 7 points (52% Republican to 45% Democrat). But what most people don’t know, including everyone who works at Politico apparently, is that among married women, Republicans still maintain a sizable 14-point advantage (56% Republican to 42% Democrat). But if Republicans are winning married men by 20 points, married women by 14 points, and unmarried men by 7 points, then who is keeping Democrats competitive? Single women are single-handedly saving the Democratic Party. By a 37-point margin (68% to 31%), single women overwhelmingly pulled the lever for Democrats. Any discussion of polarization really does need to put that fact front and center — why have single women become such political outliers?

Over the past several years, the popularity among young people of the sort of identity politics and “oppression is everywhere” mindset popularized by such authors as Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo has inevitably contributed to young people’s generally poorer mental states. As I wrote in a previous essay:

Ibram X. Kendi’s and Robin DiAngelo’s form of identity politics and victimization, besides being based on false assumptions, will tend to inculcate more feelings of loss of control among people -- and lead to less, not more, life satisfaction. As Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay write in their book Cynical Theories: “Critical Race Theory’s hallmark paranoid mind-set, which assumes racism is everywhere, always, just waiting to be found, is extremely unlikely to be helpful or healthy for those who adopt it. Always believing that one will be or is being discriminated against, and trying to find out how, is unlikely to improve the outcome of any situation. It can also be self-defeating. In The Coddling of the American Mind, attorney Greg Lukianoff and social psychologist Jonathan Haidt describe this process as a kind of reverse cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which makes its participants less mentally and emotionally healthy than before. The main purpose of CBT is to train oneself not to catastrophize and interpret every situation in the most negative light, and the goal is to develop a more positive and resilient attitude towards the world, so that one can engage with it as fully as possible. If we train young people to read insult, hostility, and prejudice into every interaction, they may increasingly see the world as hostile to them and fail to thrive in it.” As if to illustrate this perverse dynamic, Noah Lyles, a young American bronze medal winner at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, said during an interview that the previous year had been very difficult for him. When asked about his depression, Mr. Lyles said “the Black Lives Matter movement started gaining a lot of traction. That’s when the depression took over. You hear on the news every day that you’re not wanted. You love your country, but it hurts even more to see that the country they want you to support is trying to kill you.” Kendi’s and DiAngelo’s promotion of a false sense of ubiquitous “systemic racism” can all too easily reorient kids’ mental software and reprogram them to maximize their likelihood of depression, or failure. Instilling kids with a false sense that they’re surrounded by “structural racism” can only work to deny them a sense of agency in life, which will hurt their life prospects. That’s the opposite of the approach taken by early civil rights leaders. As Adrian Wooldridge points out in "The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World,” “[S]lavery and Jim Crow helped to destroy African-Americans’ sense of agency” and (emphasis added) “The self-help movement tried to restore that sense of agency both on an individual and a collective level. The central figure in this was W. E. B. Du Bois, one of the founding members of the NAACP.”

Indeed, too much emphasis on the subject of mental health itself can have the negative effect of encouraging people to focus so much on mental health issues that they come to perceive mental health issues where they might not actually exist. As Clay Routledge writes in the Wall Street Journal:

[D]welling on mental health too much can exacerbate psychological distress. Psychologists Lucy Foulkes and Jack Andrews explain in a recent article in New Ideas in Psychology that mental-health awareness campaigns may be encouraging people to interpret mild forms of distress as being severe, which in turn can make distress worse. Everyone worries, but if someone who experiences mild anxiety begins to view himself as struggling with a serious mental illness, he is likely to become more fixated on what worries him and more avoidant of anxiety-provoking experiences. This reinforces the anxious voice in his mind that says such things should be feared, which will make his anxiety worse, not better.

As Abigail Shrier writes:

In fact, far too many American children and adolescents without debilitating mental disorders have already been funneled into the slippery mental-health pipeline. I know: I’ve spoken to hundreds of parents of such kids. In 2024, I published Bad Therapy, an investigation into the surge in adolescent mental-health diagnoses and psychiatric prescription drug use. Many young people without serious mental illness nonetheless spend years languishing with a diagnosis, alternately cursing it and embracing it, believing they have a broken brain, convincing themselves that their struggles are insurmountable because of the disorder’s constraints. They meet regularly with a therapist or school counselor on whom they become increasingly reliant, losing a sense of efficacy, unable to navigate on their own even minor setbacks and interpersonal conflicts. They begin courses of antidepressants that carry all kinds of side effects—suppressed libido, fatigue, the muffling of all emotion, and even an increase in depression. Antianxiety drugs and the stimulants given to kids diagnosed with ADHD are both addictive and ubiquitously abused. Often that tragic descent begins with a simple mental health survey. By chance, while I was writing the book, my middle school–age son returned home from sleepaway camp with a persistent stomachache. I took him to urgent care, where a nurse asked me to leave the room so he could administer a mental health screening tool put out by our National Institute of Mental Health. That turned out to be NIMH explicit protocol: ask parents to leave so that you can administer the following questions to kids who have not shown any signs of mental distress, aged eight and up. I requested a copy of the survey and photographed it. Here, verbatim, are the five questions the nurse intended to put to my son in private:

1. In the past few weeks, have you wished you were dead?

2. In the past few weeks, have you felt that you or your family would be better off if you were dead?

3. In the past week, have you been having thoughts about killing yourself?

4. Have you ever tried to kill yourself? If yes, how? When?

5. Are you thinking of killing yourself right now? If yes, please describe.

Kids are wildly suggestible, especially where psychiatric symptoms are concerned. Ask a kid repeatedly if he might be depressed—how about now? Are you sure?—and he just might decide that he is. Introduce “gender dysphoria” into a peer group, and a swath of seventh grade girls are likely to decide they were born in the wrong body. Introduce “testing anxiety” or “social phobia,” or “suicidality” to them, and many teens are likely to decide: I have that, too. There is a reason clinicians keep anorexia patients from socializing unsupervised in a hospital ward; anorexia is profoundly socially contagious. “Mandatory school screenings of kids for mental illness is great in theory and terrible in practice,” Dr. Allen Frances, Duke University professor of psychiatry and author of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, widely known as the “psychiatric bible,” wrote to me over email. “Most kids who screen positive will have transient problems, not mental disorder. Mislabeling stigmatizes and subjects them to unnecessary treatments, while misdirecting very scarce resources away from kids who desperately need them.” A certain amount of anxiety and low mood is not only a normal part of every life, they are almost a signal feature of adolescence, reflecting dramatic periods of psychosocial and psychosexual change. What might look like depression in an adult is very often just a phase in a teenager. But informing a teen that he has shown signs of “depression” is no neutral act. Handing a mental diagnosis to a child or teen—even if accurate—is an enormously consequential event. It can change the way a young person sees himself, create limitations for what he believes he can achieve, encourage treatment dependency on a therapist, and empty out his sense of agency—that he can, on his own, achieve his goals and improve his life. And unlike the alleged benefits of mental health screeners, there is solid evidence on the harms produced by receiving a mental diagnosis, harms that are pure tragedy in the case of misdiagnosis. In fact, there is no proof that mental health screeners have ever been shown to improve mental health outcomes. Nor are screeners capable of identifying who the next school shooter will likely be. They are poor at identifying which kids likely have depression, since they are not sensitive enough to distinguish it from normal periods of sadness. They do not even reliably indicate which kids are at risk of suicide. What mental health surveys reliably produce is false positives. Screening for low-probability diagnoses like suicidality or clinical depression will inevitably generate a surf of misdiagnosis. It isn’t hard, mathematically, to see why. Whenever you screen very large numbers of people for very low-incidence conditions, even with good tests, false positives will overwhelm accurate diagnoses. Making reasonable assumptions about the suicide rate in an adolescent population, the overwhelming majority of students flagged for suicidality will be false positives. “If you do the statistical calculation, you discover that the false positive rate is about 97 percent,” said Stephen J. Morse, professor of law and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. That’s a lot of kids whose lives and self-conceptions the state will have altered with false alarms … “Trauma” is not a recognized mental health diagnosis. As I encountered during my investigation, in the hands of school counselors, “trauma” can and does mean any hurt suffered in childhood. Have your parents ever spanked you? Yelled at you? Forced you to attend church? Do they offer enthusiastic affirmation of your chosen gender identity, or are they skeptical? All of these are routinely identified as sources of childhood “trauma.” And because teachers and school mental health staff are all “mandatory reporters,” anything they learn about a family’s private life that carries even a whiff of “trauma” may occasion a call to Child Services … [W]hen a school informs a family that their child has been flagged for depression, it pinballs the family across a plane of panic, setting up intervention by school counseling staff and referrals for psychiatric diagnosis and medication … Especially in the last generation, adolescent mental health has leaped off a cliff—all while we have doubled and redoubled resources spent on adolescent mental health … The vast majority of our kids and teens are not mentally ill. But they are lonely, worried, scared, and bummed out. Schools ought to supply them with reliable bolsters to the human spirit: high expectations. Greater independence and responsibility. Far, far less screen time. More recess. Exercise. Art. Music. Involvement in goal-oriented activities that lure them out of their own minds and force them to think about something, anything, other than themselves.

As Layard and De Neve write, the modern liberal progressive ideology, in emphasizing ubiquitous oppression based on false assumptions, acts in direct opposition to what has become the most effective means of reducing depression, which is a series of mental exercises known as “cognitive behavioral therapy”:

[I]n the 1970s a completely new approach was developed by Aaron T. Beck. This approach was based on the key facts that our thoughts affect our feelings, we can (up to a point) choose to think differently and therefore, we can directly affect our feelings … Beck altered his treatment. He got his patients to observe their ‘negative automatic thoughts’ and replace them with thoughts of a more constructive kind. In 1977, Beck published the first randomised controlled trial of cognitive therapy for depression, comparing it with the leading anti-depressant. The results were striking – cognitive therapy was more effective. Since then there have been thousands of such trials, and the current wisdom is that cognitive therapy and anti-depressants are equally effective at ending a serious depressive episode. But, after the depression ends, anti-depressants have no effect on the risk of subsequent relapse (unless you go on taking them), while cognitive therapy (once experienced) halves the subsequent rate of relapse. And so was born Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy (CBT), which focuses on helping people change unhelpful patterns of thinking and thus bring about changes in behaviour, attitude and mood … In his presidential address to the American Psychological Association in 1998 Seligman proposed a new concept called Positive Psychology. This applies the same principles as CBT to the lives of everybody. Everybody, it says, can be happier if they have better control of their mental lives and more sensible goals.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll explore one of the other five elements of well-being, namely family and children.