False Beliefs in Witchcraft (Like False Beliefs in Ubiquitous Racism) Breeds Mistrust and Poverty – Part 1

The harmful effects of belief in the false assumptions underlying “antiracism” and “equity” parallel the harmful effects of false beliefs in witchcraft.

In previous posts (combined in one PDF file for free download here), I described how the most popular “woke” books, including Ibram X. Kendi’s “How to Be An Antiracist” and Robin DiAngelo’s “White Fragility” simply assume racism is the cause of various disparities in outcomes among people grouped by race, just like medieval witch-hunter assumed witchcraft was behind various bad outcomes for people, such as poor crop yields. The deeply flawed methodologies used by the medieval witch-hunters caused mass hysteria — including false fears of witchcraft and the pitting of one neighbor against another — that replaced social cooperation with mutual distrust. The similarly flawed methodologies of the most popular “woke” books, when employed to promote policies designed to enforce what’s become known as “equity” (that is, equal outcomes based on race) based on false assumptions of racism, are also creating false fears of racism, pitting neighbor against neighbor, and replacing social cooperation with mutual distrust.

I recently came across a fascinating study by Boris Gershman, an economics professor at American University, who applied statistical analysis and found widespread witchcraft beliefs negatively impact a country’s fiscal health.

Of course, belief in witchcraft has diminished in the West (even as false assumptions of racism as the sole cause of disparities has risen), but belief in witchcraft remains prevalent in Africa. As an article in the Los Angeles Times explains:

From the years 2005 to 2011, over 3,000 people were put to death in Tanzania for the crime of witchcraft. Before that, around 50,000 to 60,000 more were killed between 1960 and 2000 for the same reasons. The majority of these victims were elderly women, who fit the Tanzanian witch stereotype. However, accusations have been made on all grounds, such as if a woman has red-tinted eyes. Others were accused of simply living in poverty. Or if the village had a poor harvest. Or blamed for uncontrollable diseases such as HIV. No matter the justification, these women were shown no mercy in their deaths: beaten, chased, stoned and in more dramatic cases, burned or buried alive. In most instances, the murderers did not face punishment as law enforcement is stretched thin over the region.

And as one scholar explains:

Tanzania is not alone of course in carrying this burden - in 2009 the Gambian president Yahya Jammeh had 1,000 people kidnapped on suspicion of witchcraft, and forced them to drink hallucinogenic potions in order to confess; witch-lynchings in Kenya are common enough that officials have turned to sanctioned exorcisms to prevent murder, and sporadic outbreaks of unknown diseases can cause communities to turn on one another, as happened in the Congo in 2001, where around 400 people were killed in a spasm of witchcraft-related violence. Many of these incidents are the result of intra and inter community tensions, where the authorities attempt to mediate and pacify to prevent rising violence. But sometimes the state itself can look to purge a country of witches, often resorting to magical methods itself to track them down and interrogate suspects … Ghana is considered to be a modest success story, relative to many of its neighbours. Looking at measurements of democratic institutions, healthcare, poverty and economic growth, Ghana has performed well since its independence in 1957. However, belief in witchcraft is highly prevalent across the country, manifesting in a number of ways. One such is the well documented phenomenon of the ‘spirit child’, called chichuru or kinkiriko. These are believed to be malevolent spirits who inhabit the body of a newborn child, often manifesting in disabilities or deformities. Infanticide in these cases is very common, but difficult to study. One analysis recorded that 15% of all infant deaths under 3 months old was due to chichuru infanticide, typically using a concoction of lethal herbs and/or exposure to the elements. Such is the strength of belief in chichuru that health professionals will fail to report suspected infanticide cases, even in hospitals … A meningitis outbreak in 1997 killed nearly 550 people across northern Ghana and led to vigilante attacks on older women. Several were lynched and others beaten and stoned to death. Outraged NGOs and journalists began investigating the conditions for women, particularly in northern Ghana, and discovered a shocking reality. Not only were women being killed as witches in higher numbers than expected, but many thousands of women were fleeing to makeshift camps - witch’s camps. Pieces appeared in the international cosmopolitan press, decrying the conditions, particularly at the largest such camp - Gambaga - in the north east region of the country. Between the 60’s and the 90’s there was a feeling amongst scholars that African witchcraft would simply ‘go away’, under the combined pressures of modernisation and globalisation. But this didn’t happen. Researchers such as Jean and John Comaroff and Peter Geschiere began pointing out that witchcraft and the fears surrounding it intensified and morphed as different African nations began to develop, both politically and economically … As of today Ghana has around six functioning witch camps, although others have opened and closed. Three of them - Gushegu, Nabuli and Kpatinga - are located in the Gushegu district. The infamous Gambaga witch camp is in the East Mamprusi district, and the Gnani and Kukuo camps are located in Yendi and Nanumba South districts. The exact number of residents is unclear, several thousand is a rough estimate.

Gershman’s study found that witchcraft beliefs in parts of 19 countries in sub-Saharan Africa caused a significant decline in trust, mutual assistance, personal interactions and other elements of social capital that caused economic impediments. Gershman then looked at data from 23 other countries in Asia, Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East with areas of prevalent witchcraft belief and found a similar connections to failing economies, both national and local. According to Gershman, “Witchcraft beliefs are likely to erode trust and cooperation due to fears of witchcraft attacks and accusations. The evil eye leads to underinvestment and other forms of unproductive behavior due to the fear of destructive envy, where envy is likely to manifest in destruction and vandalism involving those who own wealth.”

Let’s look more closely at Gershman’s study on the effects of false witchcraft beliefs on social cooperation, with an eye toward seeing how it might help us understand better the effects of false assumptions of racism on social cooperation.

To more fully explain the analogy here, a false belief in witchcraft entails a belief not only in the ill-intent of the witch, but also in the powers of the witch to do harm through supernatural means. A false belief in racism as the sole cause of disparities also entails a belief in the ill-intent of the racist. But instead of believing the racist has supernatural powers, it’s the false accusers themselves who seek to use that false belief to exercise powers of their own – such as the power to alter the behavior of others — by “cancelling” them in various ways, such as pressuring them not to speak, or to engage in various acts of contrition — or to alter their behavior in many other unjustifiable ways. And these powers of the false accusers aren’t supernatural. Instead, those powers are based on the exploitation of all-too-natural tendencies of human psychology (just as magicians today exploit human psychology when they perform magic tricks, as demonstrated in this experiment in which a magician got 32% of participants to report having seen non-existent objects).

In his article entitled “Witchcraft Beliefs and the Erosion of Social Capital: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa and Beyond,” Gershman writes:

[O]ur argument fits with the thesis advanced by Fukuyama (1995) that “social capital, the crucible of trust and critical to the health of an economy, rests on cultural roots.” This study is also directly related to the strand of literature that examines the social costs of culture, specifically the extent to which certain traditional norms and practices may represent obstacles to economic development. Notable contributions that provide qualitative summary analyses of the inhibiting role of witchcraft beliefs include Kohnert (1996) and Platteau (2009; 2014). Both authors argue that the fears generated by witchcraft beliefs suppress individual wealth accumulation, mobility, and incentives for economic self-advancement more generally. They further note that, far from being a relic of the past, witchcraft beliefs interfere with current development aid projects in Africa and are commonly used as a tool for political and ideological intimidation. This paper extends the list of potential negative side-effects of witchcraft beliefs by exploring their connection to social capital.

Next Gershman defines witchcraft beliefs:

[T]here are a few core features characterizing witchcraft beliefs that are common for most societies. First, witchcraft is normally used to explain the origins of misfortunes, especially unexpected ones, such as illness or death, crop failure, and business problems. Second, malevolent acts of witches are believed to be driven by hostile feelings like envy, jealousy, resentment, hatred, greed, or desire for revenge.

Similarly, false assumptions of racism are used by Ibram X. Kendi and others to explain disparate social outcomes, and some are driven by a desire for some kind of “revenge,” or at least a form of reparations for what are alleged to be the current effects past injustices.

Gershman continues:

An overview of ethnographic case studies suggests that there are two main reasons for being suspicious, distrustful, and non-cooperative in a society with widespread witchcraft beliefs: the fear of bewitchment and the fear of witchcraft accusations. Importantly, while the former presumes personal belief in witchcraft, the latter only requires the belief to be maintained by other community members.

Similarly, the fear of false accusations of racism only requires that a false belief of ubiquitous racism be maintained by some critical mass of other community members in order to engender distrust within that community.

Gershman then provides some case-specific evidence of the anti-social effects of witchcraft beliefs:

Plenty of anecdotal evidence on the corrosive effects of witchcraft beliefs on social relations comes from Tanzania, where, according to Green (2005), such beliefs are a “taken-for-granted aspect of daily life for most people in most communities.” Based on her fieldwork in the districts of Ulanga and Kilombero, the author concludes that the ubiquity of witchcraft beliefs and accusations “contributes to a culture of suspicion and mistrust of kin and neighbours, in which those seeking to establish businesses or succeed in their agricultural activities feel perpetually under threat from those whom they know to be jealous and whom they believe wish them to fail.” Similarly, in the Tanzanian town of Singida widespread witchcraft beliefs breed “uncertainty, suspicion, and mistrust,” while people are afraid that “their fellow business owners may practice witchcraft” to get rid of competitors (Tillmar, 2006). In the Musoma Rural district, parents “discourage their children from eating in neighbours’ houses and interacting with strangers” because of the fears of witchcraft attacks and accusations, that is, the norm of mistrust is inculcated from early on (Nyaga, 2007).

Nombo (2008) makes another powerful case based on her fieldwork in the Mkamba village, Tanzania, where people are reluctant to cooperate and help each other due to witchcraft-related fears. For instance, they refuse to provide food assistance to their neighbors because they are afraid of witchcraft accusations in case someone gets sick after eating the contributed food. Most villagers admitted in a survey that one of the main reasons for the decline in trust is the danger of witchcraft accusations. Nombo concludes that such anxiety seems to “damage intra-community relations by eroding trust, which is the glue that holds communities together.”

South Africa is another country in which extensive fieldwork on witchcraft beliefs and accusations has been conducted. Golooba-Mutebi (2005) shows vividly how the latter are a constant source of tensions in a small village of South African Lowveld. As observed by the author, the main consequence of witchcraft beliefs for social relations has been the depletion of trust. As in Nombo (2008), in one-on-one interviews villagers explained that concerns about witchcraft were one of the main reasons for the evident lack of trust between people. Some of them admitted to have rejected other people’s help in the form of food due to the fear of being poisoned by a witch. Beyond that, violent sanctions applied to alleged witches are truly terrifying since anyone might find himself in the position of being accused. Such lack of trust prevents cooperation and collective action: attempts to establish mutual assistance groups “have collapsed amidst suspicions and accusations of witchcraft.” In addition, Golooba-Mutebi (2004) writes about the general decline in various forms of socializing, such as collective drinking and partying. In order to protect themselves from possible accusations or witchcraft attacks people generally try to minimize any interaction with other community members.

Query to what extent some people today avoid social situations, or social media interactions, with others in order to avoid the potential for false accusations of racism. Gershman continues:

Ashforth (2002) argues, again in South African context, that “in communities where a witchcraft paradigm informs understandings about other people’s motives and capacities, life must be lived in terms of a presumption of malice.” The “presumption of malice” feeds collective paranoia and makes it difficult to build networks of trust which has “practical implications for civil society and the building of social capital.” This view is echoed by Kgatla (2007) who states that “the fear of being pointed out as a witch and the consequences that may follow from such an accusation keep people in a constant state of agony.

Query to what extent “cancel culture” in America today engenders constant fears of false accusations of racism.

Gershman then makes the following commentary:

Interestingly, while early literature stressed that accusations happened most often among members of the same tight social network, more recent studies notice a shift in this traditional pattern towards greater levels of anonymity, especially in an urban setting (Lindhardt, 2009; Leistner, 2014). This new line of literature suggests that over time, as African societies modernize economically and people engage in more regular interactions with strangers away from home, witchcraft beliefs and accusations are likely to disrupt social relations beyond the networks of relatives and neighbors.

Sound familiar to you here in America? Beyond urbanization, social media has exponentially broadened the opportunities of anonymous social interaction, and as a result it should be no surprise that false accusations of racism have exponentially proliferated as well. Indeed, a previous essay described recent data indicating mere claims of racism made on social media may be increasing current misperceptions of the prevalence of racism in real life.

Gershman then expands the scope of his analysis:

Overall, anecdotal evidence suggests that witchcraft-related fears are capable of eroding social capital which may in turn hinder economic development. The rest of the paper goes beyond case studies to conduct a systematic empirical analysis of the relationship between witchcraft beliefs and social capital in Sub-Saharan Africa and beyond.

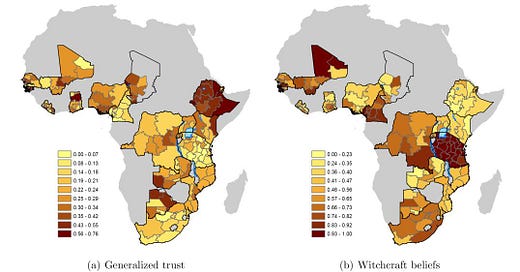

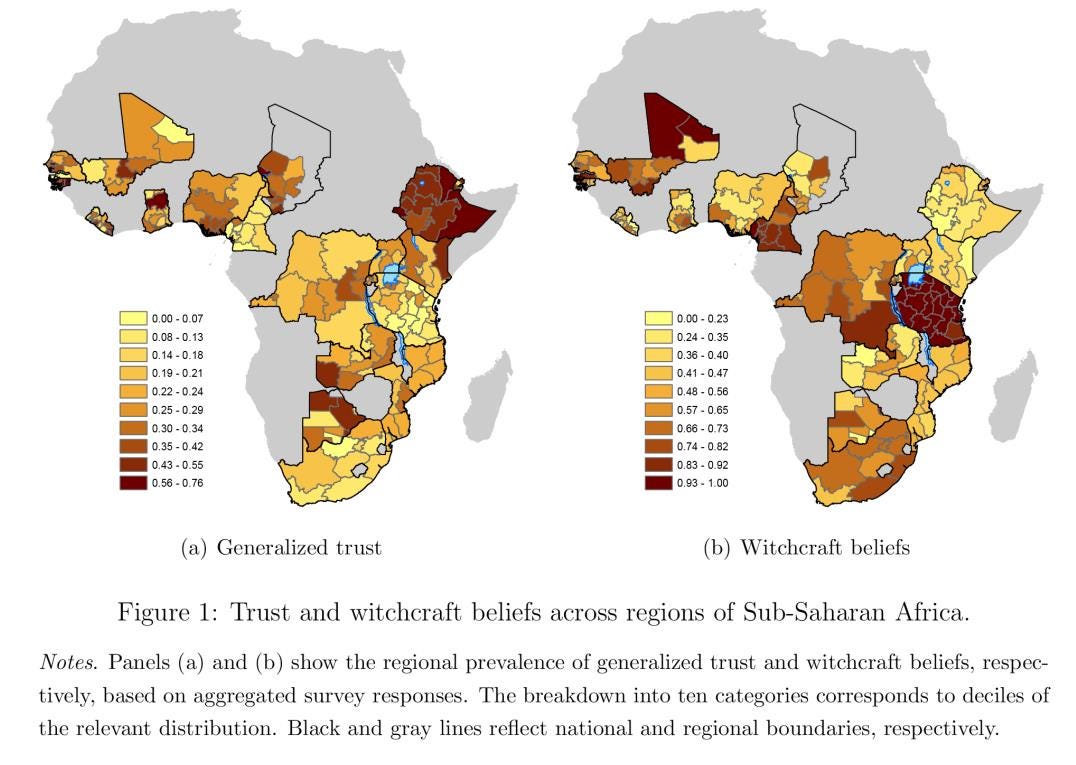

Gershman presents the following graphics, which show in both map and scatterplot form that the geographic areas in which belief in witchcraft predominates are associated with lower incidence of generalized trust:

Gershman continues:

Witchcraft beliefs are also negatively related to trust in local institutions, such as police, courts, and local government council. The relationship is much weaker and insignificant for trust in “larger government” as represented by the army, president, parliament, and the electoral commission.

Again, does any of this ring true in America? Certainly false assumptions of racism have reduced trust in local police forces in many urban areas, while it has encouraged federal policy responses based on those false understanding of racism to be implemented by the President and Congress at the “larger government” level. Indeed, Gershman finds that the mistrust created by belief in witchcraft at the local level can translate into a much larger regime of social control:

More generally, witchcraft-related fears induce people to conform to the status quo making witchcraft beliefs a special “technique of social control” that may contribute to social cohesion (Kluckhohn, 1970). In other words, witchcraft beliefs help to support a special kind of social order based on fear and forced conformity rather than cooperation, trust, and mutual solidarity. The side-effects, or social costs, of this way to maintain stability include mistrust and other elements of antisocial culture.

It’s worth querying whether support for a “social order based on fear and forced conformity rather than cooperation, trust, and mutual solidarity” is becoming ingrained into certain American political party platforms as well.

In the next essay, we’ll continue to explore this topic, including how the research of others on the history of mistrust in Africa might inform an understanding of what could result from certain strains of American culture that foster similar mistrust today.