Big Steps in the Story of Big History – Part 9

How Western religion contributed to the rise of mass literacy, monogamy, and, ultimately, individualism.

As Joseph Henrich writes in his book The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous:

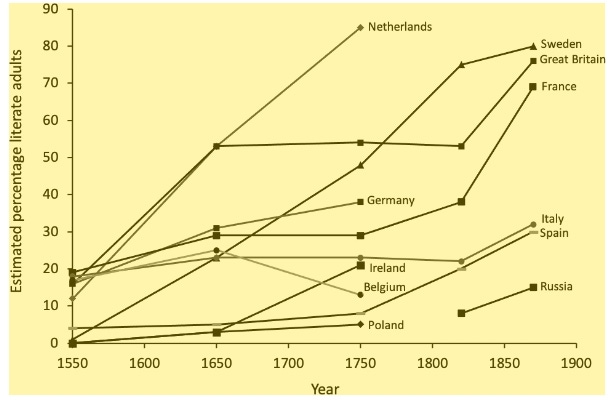

Writing systems have existed for millennia in powerful and successful societies, dating back some 5,000 years; yet until relatively recently, never more than about 10 percent of any society’s populations could read, and usually the rates were much lower. Suddenly, in the 16th century, literacy began spreading epidemically across western Europe. By around 1750, having surged past more cosmopolitan places in Italy and France, the Netherlands, Britain, Sweden, and Germany developed the most literate societies in the world … Half or more of the populations in these countries could read, and publishers were rapidly cranking out books and pamphlets. FIGURE P. 1. Literacy rates for various European countries from 1550 to 1900. These estimates are based on book publishing data calibrated using more direct measures of literacy … Luther’s Ninety- Five Theses marked the eruption of the Protestant Reformation. Elevated by his excommunication and bravery in the face of criminal charges, Luther’s subsequent writings on theology, social policy, and living a Christian life reverberated outward from his safe haven in Wittenberg in an expanding wave that influenced many populations, first in Europe and then around the world … Embedded deep in Protestantism is the notion that individuals should develop a personal relationship with God and Jesus. To accomplish this, both men and women needed to read and interpret the sacred scriptures— the Bible— for themselves, and not rely primarily on the authority of supposed experts, priests, or institutional authorities like the Church. This principle, known as sola scriptura, meant that everyone needed to learn to read. And since everyone cannot become a fluent Latin scholar, the Bible had to be translated into the local languages … In 1524, he penned a pamphlet called “To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany That They Establish and Maintain Christian Schools.” In this and other writings, he urged both parents and leaders to create schools to teach children to read the scriptures. As various dukes and princes in the Holy Roman Empire began to adopt Protestantism, they often used Saxony as their model. Consequently, literacy and schools often diffused in concert with Protestantism … The historical connection between Protestantism and literacy is well documented … [L]iteracy rates grew the fastest in countries where Protestantism was most deeply established … [T]he wave of Protestantism created by the Reformation raised literacy and schooling rates in its wake … Protestants believed that people had to become literate so that they could read the Bible for themselves, improve their moral character, and build a stronger relationship with God. Centuries later, as the Industrial Revolution rumbled into Germany and surrounding regions, the reservoir of literate farmers and local schools created by Protestantism furnished an educated and ready workforce that propelled rapid economic development and helped fuel the second Industrial Revolution … In Africa, regions that contained more Christian missions in 1900 had higher literacy rates a century later. However, early Protestant missions beat out their Catholic competitors. Comparing them head- to- head, regions with early Protestant missions are associated with literacy rates that are about 16 percentile points higher on average than those associated with Catholic missions. Similarly, individuals in communities associated with historical Protestant missions have about 1.6 years more formal schooling than those around Catholic missions. These differences are big, since Africans in the late 20th century had only about three years of schooling on average, and only about half of adults were literate … When the Reformation reached Scotland in 1560, it was founded on the central principle of a free public education for the poor. The world’s first local school tax was established there in 1633 and strengthened in 1646. This early experiment in universal education soon produced a stunning array of intellectual luminaries, from David Hume to Adam Smith, and probably midwifed the Scottish Enlightenment. The intellectual dominance of this tiny region in the 18th century inspired Voltaire to write, “We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilization.” … Let’s follow the causal chain I’ve been linking together: the spread of a religious belief that every individual should read the Bible for themselves led to the diffusion of widespread literacy among both men and women, first in Europe and later across the globe. Broad- based literacy changed people’s brains and altered their cognitive abilities in domains related to memory, visual processing, facial recognition, numerical exactness, and problem- solving. It probably also indirectly altered family sizes, child health, and cognitive development, as mothers became increasingly literate and formally educated. These psychological and social changes may have fostered speedier innovation, new institutions, and— in the long run— greater economic prosperity.

Henrich also describes how the concept of the “nuclear family” far precedes our own nuclear age, and how, in the West, a basic social unit became a metric for individualism.

In the West, the “nuclear family” is defined as “a couple and their dependent children, regarded as a basic social unit.” This generally Western concept is unique in focusing exclusively on parents and their children when defining “the family.”

As researchers wrote in 2019, starting in the Middle Ages, the Western Church tradition of discouraging cousin marriages (as was accepted elsewhere, including in the Islamic tradition) led people in cultures influenced by the Western Church to be more individualistic, independent, and trusting of strangers. The researchers found:

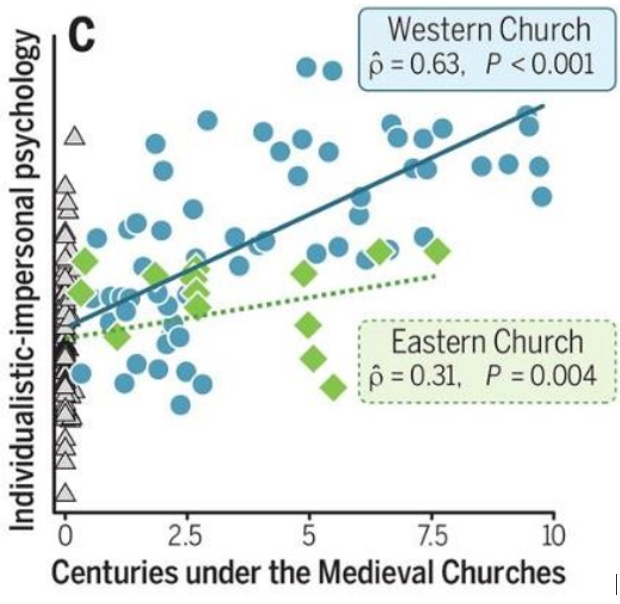

A growing body of research suggests that populations around the globe vary substantially along several important psychological dimensions and that populations characterized as Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) are particularly unusual. People from these societies tend to be more individualistic, independent, and impersonally prosocial (e.g., trusting of strangers) while revealing less conformity and in-group loyalty. Although these patterns are now well documented, few efforts have sought to explain them. Here, we propose that the Western Church (i.e., the branch of Christianity that evolved into the Roman Catholic Church) transformed European kinship structures during the Middle Ages and that this transformation was a key factor behind a shift towards a WEIRDer psychology … [H]istorical research suggests that the Western Church systematically undermined Europe’s intensive kin-based institutions during the Middle Ages (for example, by banning cousin marriage). The Church’s family policies meant that by 1500 CE, and likely centuries earlier in some regions, Europe lacked strong kin-based institutions and was instead dominated by relatively independent and isolated nuclear or stem families.

One of those researchers, Joseph Henrich, came to explore this research more fully in The WEIRDEST People in the World. As Musa al-Gharbi summarizes some of the main points in the book:

Specifically, Part II of the book … demonstrates that what is often referred to as the “traditional” family is, in fact, anything but. Looking worldwide, historically through the present, the family structure that people in the U.S. and Western Europe take for granted is actually highly peculiar — a product of a centuries-long campaign by the Western Church to dismantle kindreds, clans, tribes and other competing structures of allegiance and authority, and to reorient society around the Church instead. Central to this endeavor was what the author calls the Western Church’s Marriage and Family Program (MFP). Critically, many aspects of this program had a tenuous relationship with scripture or Christianity per se … Over time, Henrich argues, the Western Church’s MFP ended up reshaping the culture and psychology of the people under its domain, leading to significant differences between denizens of WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) countries as compared to virtually everyone else — including other places where Christianity was dominant, but the Western Church’s MFP was not. If one looks at the areas where the Western Church was able to implement its MFP from the time it was developed through the Protestant Reformation, the places that had longer exposure to the MFP, and where it was more stringently enforced, are more characteristically WEIRD today than places that have shorter or less intense exposure. This is true not just across contemporary countries, but within them as well. Henrich then illustrates how the Protestant Reformation, and later the Enlightenment, were both products and accelerators of the WEIRD revolution in culture and thought kicked off by the Western Church’s MFP. And even though the influence of the Western Church was greatly diminished over the course of these uprisings, and has been undermined further in the intervening centuries (for instance, due to growing irreligiosity in the United States and Western Europe), the Western Church’s Marriage and Family Program has largely persisted — with nuclear families continuing to serve as the foundational social unit in WEIRD societies. In fact, many non-Christian societies have ended up adopting aspects of the Western Church’s MFP in a bid to emulate the successes of “the West” (e.g. China, Turkey). To help illustrate how significant the cultural and societal changes around the Western Church’s MFP were, consider the case of (culturally) enforced monogamy. Polygyny and (especially) concubinage were fairly common in Europe prior to the ascendance of the Western Church’s MFP … [I]n polygamous societies, th[e] strong preference among women to partner with equal or (ideally) higher status men tends to create even more massive imbalances. For instance, in a society where the top 20 percent of men have 2–4 wives, while the next two quintiles involve monogamous pairings, the lower 40 percent of the male population would not be able to find wives at all. In most polygamous societies the situation was (is) far more dire than this, as men in the uppermost decile regularly had (have) several consorts, plus several concubines, leaving the majority of men in a society with almost no prospects for marriage or children. As a consequence, they often had little stake in the current order and even less investment in the future. These “excess men” were/are prone to risky and myopic behaviors in order to shake up their status or improve their prospects, including gambling, crime, insurrection at home, or raiding others abroad (often targeting women in “other” populations for rape, sexual or domestic slavery, and/or forced marriage). However, through ingenious maneuvering and some lucky breaks, the Western Church gradually managed to convince and cajole elite and relatively well-off men to more-or-less comply with monogamous marriage and other aspects of their Marriage and Family Program — thereby compelling women who could have been additional wives or concubines for these men to instead settle for lower-status partners than they would otherwise have been inclined to accept. This allowed a much wider swath of the male population to find mates and form families, giving them an incentive to work hard, follow rules, be forward-looking, patient, responsible, etc. In addition to plural marriage, taboos were enforced against … familial marriages (at its height, the MFP forbid unions to 3rd cousins or closer [and] arranged marriage (on the grounds that marriage should instead be a volitional union of two souls, based in love). Collectively, these revolutions to the family structure dramatically weakened kinship networks, over time leading to a greater sense of individuality and autonomy. The Western Church MFP enhanced mobility (the extensive taboos forced people to look outside their own communities to find acceptable partners), and led to couples marrying later and having fewer children. This, in turn, led to norms facilitating trust and collaboration with strangers — for instance, to sustain crops in a world with fewer children, delivered later in life, and with families increasingly forged among people from different communities. These cross-cutting and instrumental relationships eventually led to WEIRD notions about rules being impartial and universal (rather than being interpreted and enforced based on context, often with one standard applied to one’s in-group and a different standard applied to “others”). This, in turn, predisposed denizens of WEIRD culture towards analytical over holistic thinking about the world writ large. In conjunction with the aforementioned ethos of hard-work, rule-abidance, and planning for the future that developed among formerly-excess males, these changes facilitated the emergence of capitalism, private property, and the meritocratic ideal … Henrich persuasively demonstrates that what we in WEIRD societies describe as the “traditional family” was in fact a revolutionary form of social arrangement — one that spurred the development of many other aspects of our psychology and culture that “we” take for granted but are outliers as compared to the rest of the world. In short, conservatives are right to assert that what we call the “traditional family” serves as the foundation of Western Civilization. This is true in a very deep historical and sociological sense. Indeed, many values that liberals tend to hold dear (even sacred)— autonomy, egalitarianism, individuality — flowed from establishing the nuclear family as the core social unit (over clans, kindreds, tribes, etc.), via the very norms around sex, marriage, and family that contemporary liberals often decry as irrational and stifling … [P]rogressives who are concerned about things like uplifting people from disadvantaged backgrounds, reducing incarceration and inequality, enhancing social mobility, etc., should probably be more concerned about family structure than they typically seem to be. To say, “people should live in whatever arrangements work for them,” is to willfully ignore that the non- “traditional” family structures that a growing share of Americans end up in are clearly are not working for them — nor are they situations that many of the people involved aspired towards or willfully created, for that matter — and indeed contribute strongly to many of the social problems progressives ostensibly wish to address. Strikingly, the people most likely to be laissez-faire about others’ family structure (relatively affluent and highly-educated whites) are much more likely than virtually anyone else to hail from traditional families themselves, and to eventually establish traditional families of their own. And not for nothing: family structure and sequencing makes a huge socioeconomic difference. These relatively well-off social liberals should therefore preach what they practice.

As Henrich himself writes in The WEIRDEST People in the World, regarding monogamous marriages:

Tracking this puzzle back into Late Antiquity, we’ll see that one sect of Christianity drove the spread of a particular package of social norms and beliefs that dramatically altered marriage, transformation of family life initiated a set of psychological changes that spurred new forms of urbanization and fueled impersonal commerce while driving the proliferation of voluntary organizations, from merchant guilds and charter towns to universities and transregional monastic orders, that were governed by new and increasingly individualistic norms and laws … In short, these psychological shifts fertilized the soil for the seeds of the modern world. Thus, to understand the roots of contemporary societies we need to explore how our psychology culturally adapts and coevolves with our most basic social institution— the family … Throughout most of human history, people grew up enmeshed in dense family networks that knitted together distant cousins and in- laws. In these regulated- relational worlds, people’s survival, identity, security, marriages, and success depended on the health and prosperity of kin- based networks, which often formed discrete institutions known as clans, lineages, houses, or tribes. This is the world of the Maasai, Samburu, and Cook Islanders. Within these enduring networks, everyone is endowed with an extensive array of inherited obligations, responsibilities, and privileges in relation to others in a dense social web. For example, a man could be obligated to avenge the murder of one type of second cousin (through his paternal great- grandfather), privileged to marry his mother’s brother’s daughters but tabooed from marrying strangers, and responsible for performing expensive rituals to honor his ancestors, who will shower bad luck on his entire lineage if he’s negligent. Behavior is highly constrained by context and the types of relationships involved. The social norms that govern these relationships, which collectively form what I’ll call kin-based institutions, constrain people from shopping widely for new friends, business partners, or spouses. Instead, they channel people’s investments into a distinct and largely inherited in-group. Many kin-based institutions not only influence inheritance and the residence of newly married couples, they also create communal owner- ship of property (e.g., land is owned by the clan) and shared liability for criminal acts among members (e.g., fathers can be imprisoned for their sons’ crimes) … Success and respect in this world hinge on adroitly navigating these kin-based institutions. This often means (1) conforming to fellow in- group members, (2) deferring to authorities like elders or sages, (3) policing the behavior of those close to you (but not strangers), (4) sharply distinguishing your in- group from everyone else, and (5) promoting your network’s collective success whenever possible.

This led to an appreciation for, and legal recognition of, individualism. As Henrich writes:

Imagine the psychology needed to navigate a world with few inherited ties in which success and respect depend on (1) honing one’s own special attributes; (2) attracting friends, mates, and business partners with these attributes; and then (3) sustaining relationships with them that will endure for as long as the relationship remains mutually beneficial. In this world, everyone is shopping for better relationships, which may or may not endure. People have few permanent ties and many ephemeral friends, colleagues, and acquaintances … In adapting psychologically to this world, people come to see themselves and others as independent agents defined by a unique or special set of talents (e.g., writer), interests (e.g., quilting), aspirations (e.g., making law partner), virtues (e.g., fairness), and principles (e.g., “no one is above the law”) … More individualistically oriented people want to fully harness their skills and then draw a sense of accomplishment from their work … More individualistic countries are also richer, more innovative, and more economically productive … [C]ultural learning, rituals, monogamous marriage, markets, and religious beliefs can contribute to increasing people’s patience and self- control in ways that lay the groundwork for new forms of government and more rapid economic growth.

The religious focus on two-parent families led to psychological changes that had dramatic secular results:

[T]he medieval Catholic Church inadvertently altered people’s psychology by promoting a peculiar set of prohibitions and prescriptions about marriage and the family that dissolved the densely interconnected clans and kindreds in western Europe into small, weak, and disparate nuclear families. The social and psychological shifts induced by this transformation fueled the proliferation of voluntary associations, including guilds, charter towns, and universities, drove the expansion of impersonal markets, and spurred the rapid growth of cities. By the High Middle Ages, catalyzed by these ongoing societal changes, WEIRDer ways of thinking, reasoning, and feeling propelled the emergence of novel forms of law, government, and religion while accelerating innovation and the emergence of Western science … As you’ll see, the particular idea of endowing individuals with “rights” and then designing laws based on those rights only makes sense in a world of analytical thinkers who conceive of people as primarily independent agents and look to solve problems by assigning properties, dispositions, and essences to objects and persons. If this approach to law sounds like common sense, you are indeed WEIRD … The families found in WEIRD societies are peculiar, even exotic, from a global and historical perspective. We don’t have lineages or large kindreds that stretch out in all directions, entangling us in a web of familial responsibilities. Our identity, sense of self, legal existence, and personal security are not tied to membership in a house or clan, or to our position in a relational network. We limit ourselves to one spouse (at a time), and social norms usually exclude us from marrying relatives, including our cousins, nieces, stepchildren, and in- laws. Instead of arranged marriages, our “love marriages” are usually motivated by mutual affection and compatibility … Nuclear families form a distinct core in our societies but reside together only until the children marry to form new households. Beyond these small families, our kinship ties are fewer and weaker than those of most other societies … [T]he dissolution of intensive kin-based institutions and the gradual creation of independent monogamous nuclear families represents the proverbial pebble that started the avalanche to the modern world in Europe. Now let’s look at how this pebble was first inadvertently kicked by the Church … The roots of WEIRD families can be found in the slowly expanding package of doctrines, prohibitions, and prescriptions that the Church gradually adopted and energetically promoted, starting before the end of the Western Roman Empire.

Western culture then moved from more individualism to more democracy (that is, rule by a society of individuals). As Henrich writes:

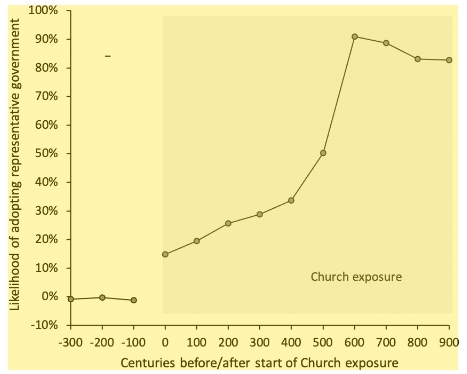

For political institutions, Figure 9.6 illustrates the impact of the Church by looking at the likelihood that a European city develops some form of representative government both before and after the Church arrives. Before the Church arrives, the estimated probability of developing any form of representative government is zero— making pre- Christian Europe just like everywhere else in the world. After the Church arrives, the chances that a city adopts some form of representative government jumps to 15 percent and then increases continuously for the next six centuries, topping out at over 90 percent. 51 FIGURE 9.6. The likelihood of urban areas adopting any form of representative government from 800 to 1500 CE based on centuries of exposure to the medieval Western Church. The shaded region captures the arrival of the Church. To the left of zero, the unshaded region is the centuries prior to the Church’s arrival … Summarizing our progress: the breakdown of intensive kin- based institutions opened the door to urbanization and the formation of free cities and charter towns, which began developing greater self- governance. Often dominated by merchants, urban growth generated rising levels of market integration and— we can infer— higher levels of impersonal trust, fairness, and cooperation. While these psychological and social changes were occurring, people began to ponder notions of individual rights, personal freedoms, the rule of law, and the protection of private property. These new ideas just fit people’s emerging cultural psychology better than many alternatives.

Interestingly, bans on cousin marriages here in the United States have been shown to yield similarly beneficial results:

Close-kin marriage, by sustaining tightly knit family structures, may impede development. We find support for this hypothesis using U.S. state bans on cousin marriage. Our measure of cousin marriage comes from the excess frequency of same-surname marriages, a method borrowed from population genetics that we apply to millions of marriage records from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. Using census data, we first show that married cousins are more rural and have lower-paying occupations. We then turn to an event study analysis to understand how cousin marriage bans affected outcomes for treated birth cohorts. We find that these bans led individuals from families with high rates of cousin marriage to migrate off farms and into urban areas. They also gradually shift to higher-paying occupations. We observe increased dispersion, with individuals from these families living in a wider range of locations and adopting more diverse occupations. Our findings suggest that these changes were driven by the social and cultural effects of dispersed family ties rather than genetics.

As explored in previous essays, these trends also dovetailed with newly-emerging Protestantism and the development of the “Protestant work ethic.” As Henrich writes:

[A] growing body of work supports the notion that Protestant beliefs and practices foster hard work, patience, and diligence … [I]f there’s a secret ingredient in the recipe for Europe’s collective brain, it’s the psychological package of individualism, analytic orientation, positive- sum thinking, and impersonal prosociality that had been simmering for centuries. The relationship between psychology and innovation can still be seen today. Using data on patents to assess innovation rates, Figure 13.5 shows that more individualistic countries are much more innovative. FIGURE 13.5. Innovation rates and psychological individualism. Innovation here is measured using patents per million people in 2009 …

As Henrich summarizes:

To close, let’s summarize this chapter on a Post-it. To explain the innovation-driven economic expansion of the last few centuries, I’ve argued that the social changes and psychological shifts sparked by the Church’s dismantling of intensive kinship opened the flow of information through an ever- broadening social network that wired together diverse minds across Christendom. In laying this out, I highlighted seven contributors to Europe’s collective brain: (1) apprenticeship institutions, (2) urbanization and impersonal markets, (3) transregional monastic orders, (4) universities, (5) the Republic of Letters, (6) knowledge societies (along with their publications like the Encyclopédie), and (7) new religious faiths that not only promoted literacy and schooling but also made industriousness, scientific insight, and pragmatic achievement sacred. These institutions and organizations, along with a set of psychological shifts that made individuals more inventive but less fecund, drove innovation while holding population growth in check, eventually generating unparalleled economic prosperity. FIGURE 14.1 [below] is an outline of the main processes described in this book.

Cultural anthropologists have noted that while about 85 percent of human societies throughout history allowed men to have more than one wife, the relatively rapid and recent proliferation of monogamous marriages worldwide has been the result of its many advantages for husbands, wives, and children. As summarized in a 2012 article:

The anthropological record indicates that approximately 85 per cent of human societies have permitted men to have more than one wife (polygynous marriage), and both empirical and evolutionary considerations suggest that large absolute differences in wealth should favour more polygynous marriages. Yet, monogamous marriage has spread across Europe, and more recently across the globe, even as absolute wealth differences have expanded. Here, we develop and explore the hypothesis that the norms and institutions that compose the modern package of monogamous marriage have been favoured by cultural evolution because of their group-beneficial effects-promoting success in inter-group competition. In suppressing intrasexual competition and reducing the size of the pool of unmarried men, normative monogamy reduces crime rates, including rape, murder, assault, robbery and fraud, as well as decreasing personal abuses. By assuaging the competition for younger brides, normative monogamy decreases (i) the spousal age gap, (ii) fertility, and (iii) gender inequality. By shifting male efforts from seeking wives to paternal investment, normative monogamy increases savings, child investment and economic productivity. By increasing the relatedness within households, normative monogamy reduces intra-household conflict, leading to lower rates of child neglect, abuse, accidental death and homicide. These predictions are tested using converging lines of evidence from across the human sciences.

This concludes this series of essays on Big History. In the next series of essays, we’ll more closely examine the data that shows how the gift of the two-parent family is a gift that just keeps on giving and giving.

[READERS NOTE: As I’m currently working on another, short-term project, during that time new essays on the Big Picture will only appear once a week (on Mondays) instead of twice a week. Once more of my time frees up again, I’ll go back to twice-weekly postings.]