We ended the last essay with a discussion of the vast scale and detrimental consequences of current federal student loan forgiveness programs. A policy that makes it so young people don’t have to work to repay the student loans they had agreed to pay back can only further weaken the influence of the work ethic in America. So, too, will mortgage policies such as the following, described by the Wall Street Journal:

It was probably inevitable that the Biden Administration would enlist housing giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to advance its woke agenda, and now it has. Last week the government-sponsored enterprises released plans to promote housing “equity” that are chock-full of race-based subsidies. Fannie and Freddie have been under federal conservatorship since Treasury rescued them during the housing meltdown with a $190 billion taxpayer bailout. The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) has since regulated their capital, liquidity and underwriting, as well as the mortgages they can acquire. Trump FHFA director Mark Calabria kept the monsters on a tight leash, but there was always a risk that a future Administration would ease up and politicize home lending again. That day has come. In September the Biden FHFA announced it would require Fannie and Freddie to “prepare and implement three-year Equitable Housing Finance Plans that describe each Enterprise’s planned efforts to advance equity in housing finance.” Translation: They must find ways to boost minority homeownership no matter the risk for taxpayers. The plans released last week might have been written by California Rep. Maxine Waters. Central to Fannie’s plan are “Special Purpose Credit Programs” that increase access to credit and encourage “sustainable homeownership for Black consumers.” One program would assist black borrowers with down payments. Most home-buyers are required to put down at least 20% of the cost of a new home to reduce the risks of default. Fannie’s plan would effectively require taxpayers to subsidize down payments for black borrowers. Revenue that Fannie earns on its mortgage portfolio is retained as capital to protect taxpayers during a downturn. Under Fannie’s plan, some of that revenue would go to reducing down payments. Another new program would reduce “loan level price adjustments” for black home buyers. Lenders typically charge higher rates for borrowers with lower credit scores, and Fannie says reducing them can “reduce obstacles for prospective Black homeowners.” Still another program would “support the reduction of borrower closing costs for Black homebuyers”—for instance, via appraisal reimbursements. Taxpayers would help finance this “support.” Fannie also wants to help black homeowners avoid foreclosure by helping them “deal with unexpected expenses and repairs, or temporary disruptions to income.” This suggests that Fannie may now push into funding home repairs and welfare … Fannie says these credit subsidies are merely “pilot programs” that will be tested “in predominantly Black geographic markets”—i.e., big liberal cities—and evaluated based on “applications made to participating lenders from Black consumers” and “loans to Black borrowers.” But government housing subsidies always start small and expand as they develop a vested constituency … Fannie makes its subsidies for blacks explicit, but they don’t appear to extend to other racial groups such as Hispanics and Asians. Low-income white borrowers are also excluded.

As the Wall Street Journal wrote in April, 2023, that policy became a new rule:

Income redistribution is an abiding value of the Biden Administration, and now it wants to spread that to mortgage lending. A new rule will raise mortgage fees for borrowers with good credit to subsidize higher-risk borrowers. Under the rule, which goes into effect May 1, home buyers with a good credit score over 680 will pay about $40 more each month on a $400,000 loan, and upward depending on the size of the loan. Those who make down payments of 20% on their homes will pay the highest fees. Those payments will then be used to subsidize higher-risk borrowers through lower fees. This is the socialization of risk, and it flies against every rational economic model, while encouraging housing market dysfunction and putting taxpayers at risk for higher default rates. The 20% down payment is a financial discipline that encourages buyers to seek homes they can afford, and it gives buyers skin in the borrowing game. No one wants to default on a mortgage when they could lose tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in equity they’ve built up in their homes. Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) director Sandra Thompson says the rule will “increase pricing support for purchase borrowers limited by income or by wealth.” The Biden Administration may want more homeownership, but selling people houses they can’t afford has never been a good idea. See the subprime loan collapse of 2008 … The biggest problem here is fairness. Taxpayers already subsidize mortgages for low-income borrowers through the Federal Housing Administration. Now they want to punish those who have maintained good credit while rewarding those who haven’t. In the name of making housing more equal, they are pursuing an inequitable policy.

As Howard Husock writes:

It may seem a favor to potential first-time homebuyers of limited income to extend them credit despite their failure to meet traditional underwriting standards. But doing so not only poses the risk that such borrowers will become delinquent and lose their homes; it also poses a risk to their neighbors — to the communities supposedly being helped. Little is more damaging to a neighborhood than vacant homes or homes whose owners can’t afford to maintain them. Therein lies the risk of extending credit to the marginal borrower … But there is a broader point here: The very process of striving and saving, including for a down payment, is an end in itself — one that requires steady employment and that rewards two-earner households and frugality. It’s worth noting that the homeownership rate for married black couples is 21 percent higher (48 versus 27 percent) than the rate for unmarried black Americans. Good personal choices lay the foundation for the higher credit scores that lead to affordable, traditional mortgage loans. Such choices should not be devalued through policies that lower the bar for prospective loanees; they should be appreciated and rewarded, because they are and have always been the key to upward mobility for Americans of all races.

As Peter Wallison adds:

[T]he FHFA announced that henceforth it would require mortgage borrowers who, because of their good credit could borrow at lower cost, to pay somewhat higher fees, while borrowers with lesser credit scores would be able to borrow at lower cost than their credit ratings would otherwise permit. Yes, it was proposing “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” for the mortgage market. Where have we heard that before? The US kulaks (i.e., middle class) might revolt when they learn that their dream house was bought for a monthly personal payment less than their offer because the buyer, with a lower credit rating, received a subsidy from Fannie or Freddie to make up for it, and the subsidy would come from buyers with higher credit ratings. They might wonder why they, meeting all their financial obligations, should be penalized when it comes to buying a home, while those who may be spending with less care will be rewarded with a lower borrowing rate.

In previous essays, we explored the influence of the “Protestant work ethic,” a phenomenon Harvard academic Samuel Huntington described as follows:

The work ethic is a central feature of the Protestant culture, and from the beginning America’s religion has been the religion of work. In other societies, heredity, class, social status, ethnicity, and family are the principal sources of status and legitimacy. In America, work is. In different ways both aristocratic and socialist societies tend to demean and discourage work. Bourgeois societies promote work. America, the quintessential bourgeois society, glorifies work. When asked “What do you do?” almost no American dares answer “Nothing.”

That’s changing now. As the Wall Street Journal reports:

Silver linings from the pandemic are few and far between, but there are some. One is that the experience has given economists new opportunities to retest old theories about matters such as unemployment benefits and the labor market. And guess what: We now have more evidence that when you pay people not to work, they won’t. That’s the conclusion of a new paper by Harry Holzer, Glenn Hubbard and Michael Strain (of Georgetown, Columbia and the American Enterprise Institute, respectively). Congress’s pandemic expansion of unemployment benefits—and several states’ resistance to that policy—created an unusual experiment that policy makers should mark. The March 2021 American Rescue Plan made unemployment benefits more generous in two ways. The law extended a program that added $300 each week to a state’s standard benefit. A separate part of the bill expanded eligibility for unemployment benefits to workers such as the self-employed who wouldn’t ordinarily qualify. Then federalism kicked in. Twenty-six states canceled at least one of the two programs before the September 2021 national phase-out set by Congress, and several of those ended one benefit but not the other. The opportunity to compare states that kept both benefits in place to those that canceled one or both provided a natural economic experiment. The results are enlightening if not surprising. Ending one or both benefits early accelerated the transition of workers from unemployment to jobs. States that ended the benefits sooner saw their jobless rates among prime-age workers fall by 0.9 percentage point. The precise scale of the effects depends on which statistical method is used to crunch the numbers, but several different techniques yield similar findings. This holds up even after the economists controlled for labor-market developments in states before they phased out one or both of the benefits in summer 2021. Meanwhile, the stark differences in employment faded after all states ended both programs in September 2021. These points signal that the unemployment benefits were the important factor, and not other tax or regulatory policies in the various states. The results confirm what many labor economists have known for a long time: The more you pay people not to work, the less work they do.

The Democrats’ 2021 American Rescue Plan, for the first time since bipartisan federal welfare reform was enacted in 1996, eliminated the welfare work requirements. As Matt Weidinger writes:

Democrats’ March 2021 American Rescue Plan. That partisan legislation sharply increased the value of the CTC, provided it in monthly installments in the second half of 2021, and paid it for the first time to parents who don’t work, effectively reviving work-free federal welfare checks that ended a generation ago on a bipartisan basis. It shouldn’t be surprising that temporarily issuing bigger government checks to tens of millions of families increased their income and thus reduced child poverty. But the massive deficit spending in the ARP and other trillion-dollar bills also contributed to higher inflation , which disproportionately hurts lower-income families . Economist Mark Zandi found the typical household today pays on average $709 more per month due to inflation than two years ago — far exceeding the maximum CTC for two children of $600 per month temporarily paid then.

Weidinger adds further that:

The design of the temporary Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program was especially flawed. As New Jersey labor commissioner Robert Asaro Angelo testified, “Fraudsters saw the pandemic as the perfect time to attack, and they saw an almost perfect target, Pandemic Unemployment Assistance or PUA….For PUA, eligibility was based solely on self-certification, and states were prohibited by law from confirming this information – the perfect recipe for fraud.”

But before Americans move even further down the path of penalizing work rather than rewarding it, it’s worth exploring the views expressed by historian Niall Ferguson in his book Civilization: The West and the Rest. Ferguson writes:

[I]t was a very specific form of Christianity – the variant that arose in Western Europe in the sixteenth century – that gave the modern version of Western civilization the sixth of its key advantages over the rest of the world: Protestantism – or, rather, the peculiar ethic of hard work and thrift with which it came to be associated. It is time to understand the role God played in the rise of the West, and to explain why, in the late twentieth century, so many Westerners turned their backs on Him. Until the Reformation, Christian religious devotion had been seen as something distinct from the material affairs of the world. Lending money at interest was a sin. Rich men were less likely than the poor to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. Rewards for a pious life lay in the afterlife. All that had changed after the 1520s, at least in the countries that embraced the Reformation. Reflecting on his own experience, Weber began to wonder what it was about the Reformation that had made the north of Europe more friendly towards capitalism than the south. Weber’s thesis is not without its problems. Nevertheless, there are reasons to think that Weber was on to something, even if he was right for the wrong reasons. There was indeed, as he assumed, a clear tendency after the Reformation for Protestant countries in Europe to grow faster than Catholic ones, so that by 1700 the former had clearly overtaken the latter in terms of per-capita income, and by 1940 people in Catholic countries were on average 40 per cent worse off than people in Protestant countries. Because of the central importance in Luther’s thought of individual reading of the Bible, Protestantism encouraged literacy, not to mention printing, and these two things unquestionably encouraged economic development (the accumulation of ‘human capital’) as well as scientific study.1This proposition holds good not just for countries such as Scotland, where spending on education, school enrolment and literacy rates were exceptionally high, but for the Protestant world as a whole. Wherever Protestant missionaries went, they promoted literacy, with measurable long-term benefits to the societies they sought to educate … It was the Protestant missionaries who were responsible for the fact that school enrolments in British colonies were, on average, four to five times higher than in other countries’ colonies. In 1941 over 55 per cent of people in what is now Kerala were literate, a higher proportion than in any other region of India, four times higher than the Indian average and comparable with the rates in poorer European countries like Portugal. This was because Protestant missionaries were more active in Kerala, drawn by its ancient Christian community, than anywhere else in India. Where Protestant missionaries were not present (for example, in Muslim regions or protectorates like Bhutan, Nepal and Sikkim), people in British colonies were not measurably better educated. The level of Protestant missionary activity has also proved to be a very good predictor of post-independence economic performance and political stability. Recent surveys of attitudes show that Protestants have unusually high levels of mutual trust, an important precondition for the development of efficient credit networks. But perhaps the biggest contribution of religion to the history of Western civilization was this. Protestantism made the West not only work, but also save and read. The Industrial Revolution was indeed a product of technological innovation and consumption. But it also required an increase in the intensity and duration of work, combined with the accumulation of capital through saving and investment. Above all, it depended on the accumulation of human capital. The literacy that Protestantism promoted was vital to all of this. On reflection, we would do better to talk about the Protestant word ethic.

Ferguson then writes:

The question is: has the West today – or at least a significant part of it – lost both its religion and the ethic that went with it? Europeans today are the idlers of the world. On average, they work less than Americans and a lot less than Asians. Thanks to protracted education and early retirement, a smaller share of Europeans are actually available for work. For example, 54 per cent of Belgians and Greeks aged over fifteen participate in the labour force, compared with 65 per cent of Americans and 74 per cent of Chinese. Of that labour force, a larger proportion was unemployed in Europe than elsewhere in the developed world on average in the years 1980 to 2010. Europeans are also more likely to go on strike. Above all, thanks to shorter workdays and longer holidays, Europeans work fewer hours. Between 2000 and 2009 the average American in employment worked just under 1,711 hours a year (a figure pushed down by the impact of the financial crisis, which put many workers on short time). The average German worked just 1,437 hours – fully 16 per cent less. This is the result of a prolonged period of divergence. In 1979 the differentials between European and American working hours were minor; indeed, in those days the average Spanish worker put in more hours per year than the average American. But, from then on, European working hours declined by as much as a fifth. Asian working hours also declined, but the average Japanese worker still works as many hours a year as the average American, while the average South Korean works 39 per cent more. People in Hong Kong and Singapore also work roughly a third more hours a year than Americans. The striking thing is that the transatlantic divergence in working patterns has coincided almost exactly with a comparable divergence in religiosity. Europeans not only work less; they also pray less – and believe less. According to the most recent (2005-2008) World Values Survey, 4 per cent of Norwegians and Swedes and 8 per cent of French and Germans attend a church service at least once a week, compared with 36 per cent of Americans, 44 per cent of Indians, 48 per cent of Brazilians and 78 per cent of sub-Saharan Africans. The figures are significantly higher for a number of predominantly Catholic countries like Italy (32 per cent) and Spain (16 per cent) … According to one scholar from the Chinese Academy of the Social Sciences: “We were asked to look into what accounted for the … pre- eminence of the West all over the world … At first, we thought it was because you had more powerful guns than we had. Then we thought it was because you had the best political system. Next we focused on your economic system. But in the past twenty years, we have realized that the heart of your culture is your religion: Christianity. That is why the West has been so powerful. The Christian moral foundation of social and cultural life was what made possible the emergence of capitalism and then the successful transition to democratic politics. We don’t have any doubt about this.”

With a declining work ethic, of course, comes a lower labor force participation rate, which has been made even worse in that, as the costs of recreational activities have fallen, hours worked have fallen as well. As researchers from The University of Pennsylvania and Cornell write:

Recreation prices and hours worked have both fallen over the last century. We construct a macroeconomic model with general preferences that allows for trending recreation prices, wages, and work hours along a balanced-growth path. Estimating the model using aggregate data from OECD countries, we find that the fall in recreation prices can explain a large fraction of the decline in hours. We also use our model to show that the diverging prices of the recreation bundles consumed by different demographic groups can account for much of the increase in leisure inequality observed in the United States over the last decades … [R]eal wages have been increasing by 2.00% per year, and real recreation prices have been declining by 1.09% per year …

As we can see from figure 7, the real price of “Audio-Video” items, disproportionately consumed by young and less-educated households, has declined by 60% since 1980.

Researchers have also shown that today’s 12th graders represent a 20-percentage point drop in students who have worked for pay at any point during their last school year.

It’s bad enough that fewer people of prime working age are working today. It’s even worse when one realizes there will be even fewer future workers coming through the civilizational pipeline, who themselves may work less overall if current trends persist.

As Mark Warshawsky reports:

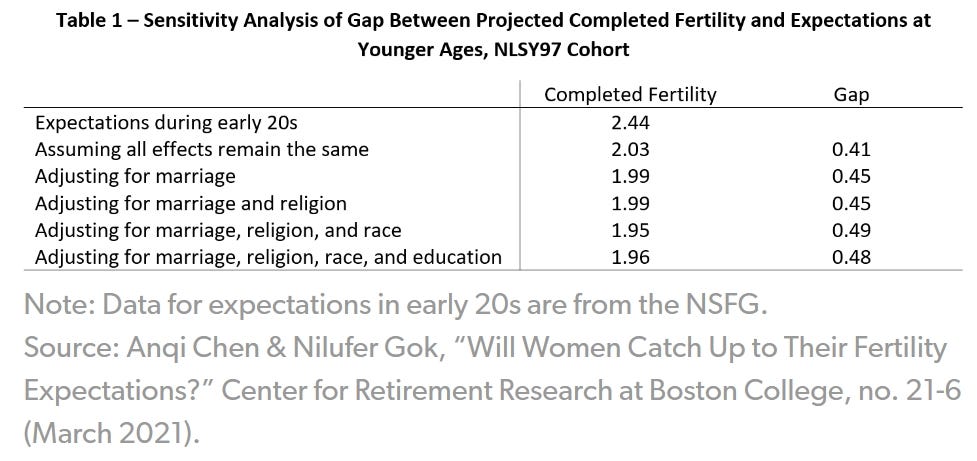

[N]ew survey evidence and analysis of the expectations of women having children over their lifetimes is consistent with an overall lower fertility rate and not just a delay in timing, as assumed by the trustees [the Social Security and Medicare Trustees] in their 2021 report. As shown below, there are two trends evident among young women, ages 20 to 24: Their realized births have already fallen by half, from 0.54 in 1982 to 0.25 in 2019, and their expectations of additional children over their lifetime fell from 1.92 to 1.84 over that period, for a decline of total children expected from 2.46 in 1982 to 2.09 in 2019. But even those lowered expectations are too optimistic, as birth realizations are always less, by 0.3 for historical cohorts. Women now in their early 30s when surveyed in their 20s indicated that they expected 2.44 children over their lifetime. Based on a regression analysis, as seen in Table 1, their projected completed fertility is 2.03, or 0.41 less than their original expectations, if nothing else changed. Further, when adjusting for important factors affecting fertility including marriage, religion, race, and education, the projected completed fertility of these women is even lower, at 1.96, or 0.48 less than their original expectations. Given that younger women now have even lower fertility expectations than their older cohorts did, a reasonable assumption for long-range fertility might go as low as 1.6 = 2.1 – 0.5, or perhaps 1.7 or 1.8 if the 2019 reading is an anomaly or the regression analysis of the expectations gap is too stark.

Using a 1.7 assumed fertility rate instead of the current assumption of 2.0 makes a big difference in the long-range financial status of the Social Security program. As seen in Table 2, the current 75-year actuarial balance is a shortfall of expenses less income of a negative 3.54 percent of taxable payroll. But if a 1.7 fertility rate is assumed, then the 75-year shortfall increases to negative 4.26, and in the 75th year, the annual balance is negative 6.69 instead of 4.34, as the lower birth rates result in fewer workers paying payroll taxes to support the system.

In a podcast interview from May 26, 2023, economist Jesus Fernandez-Villaverde said:

I’m a little bit older than I used to be and I already realized that for me to adopt new technology is now much harder than it was when I was ten years younger. As the average person in society becomes older and older, you are going to have societies that adopt fewer newer technologies, you have fewer new entrepreneurs, etc. For instance, there has been a lot of discussion that in the U.S. there are now way less new business than ten or twenty years ago … [T]his is completely driven by the fact that we have less [people] who are 25 years old. Most new firms are created by people in their twenties, late twenties, and we now have fewer people in their late twenties … [T]he percentage of people in their late twenties that create firms are the same as before, except there are less of them. So you’re going to have fewer new firms.

But whatever the age at which people tend to become successful entrepreneurs, there will be fewer of them as population declines, and there will be more and more people who are older (and less likely to spend their money to adopt new technologies).

And as Tim Carney writes:

In 2021, some declared a COVID baby boom as births went up, which never happened. We had 3.66 million, which was about 50,000 more babies than in 2020. Then, in 2022, births dipped back down to 3.61 million, according to provisional data. The earliest numbers for 2023 show things are continuing to drop. The first quarter of 2023 saw births 1% lower than the first quarter of last year.

This fertility decline is not uniform across the country. As these charts from the Economic Innovation Group show, the blue-colored states are those experiencing an increase in children age 0-4. The states gaining children are South Carolina, North Carolina, Idaho, Tennessee, and New Hampshire. States losing the most children (or where adults aren’t having them) are New York, Illinois, California, and New Mexico.

An article in the Journal of the American Economic Association also reports that:

Population aging is expected to slow US economic growth. We use variation in the predetermined component of population aging across states to estimate the impact of aging on growth in GDP per capita for 1980–2010. We find that each 10 percent increase in the fraction of the population age 60+ decreased per capita GDP by 5.5 percent. One-third of the reduction arose from slower employment growth; two-thirds due to slower labor productivity growth. Labor compensation and wages also declined in response. Our estimate implies population aging reduced the growth rate in GDP per capita by 0.3 percentage points per year during 1980–2010.

As Samuel Abrams and Joel Kotkin write:

Unmarried women without children have been moving toward the Democratic Party for several years … While married men and women as well as unmarried men broke for the GOP, CNN exit polls found that 68% of unmarried women voted for Democrats … The number of never married women has grown from about 20% in 1950 to over 30% in 2022, while the percentage of married women has declined from almost 70% in 1950 to under 50% today. Overall, the percentage of married households with children has declined from 37% in 1976 to 21% today. A new Institute for Family Studies analysis of 2020 Census data found that one in six women do not have children by the time they reach the end of their childbearing years, up from one in ten in 1990 … The Pew Research Center notes that since 1960, single-person households in the United States have grown from 13% to 27% (2019) … There is a clear economic divergence between married and unmarried women, if for no other reason than that two incomes provide more resources and children present different demands. There are plenty of renting couples and home-owning singles, but married people account for 77% of all homeowners, according to the Center for Politics. Married women tend also to do far better professionally and economically … This economic reality impacts political choices. Not part of an economic familial unit, they tend to look to government for help, whether for rent subsidies or direct transfers. The pitch of Democratic presidents as reflected in Barack Obama’s “Life of Julia” and Joe Biden’s “Life of Linda” – narratives that advertised the government’s cradle-to-grave assistance for women – is geared toward women who never marry, with the occasional child-raising addressed not by family resources but government transfers.

Fewer workers will of course invite calls for raising taxes, but doing so would produce tax burdens even more disproportionate than they already are. As the Wall Street Journal wrote in March, 2023:

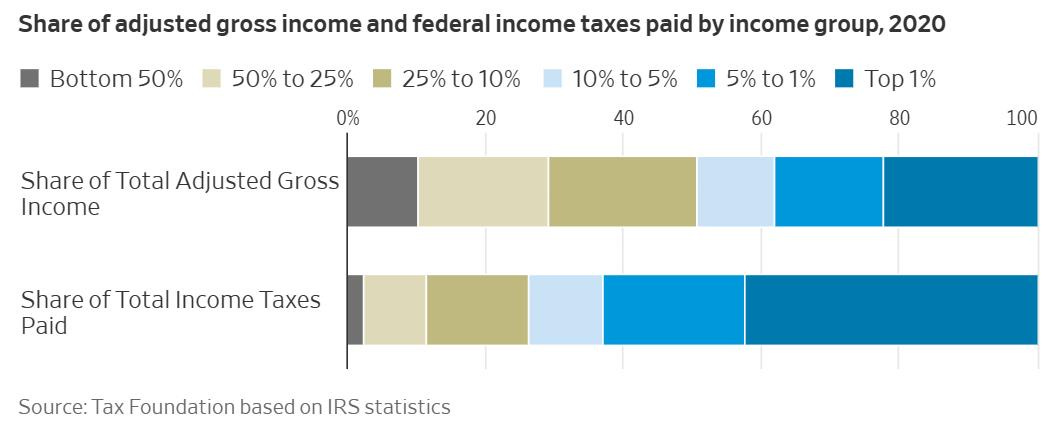

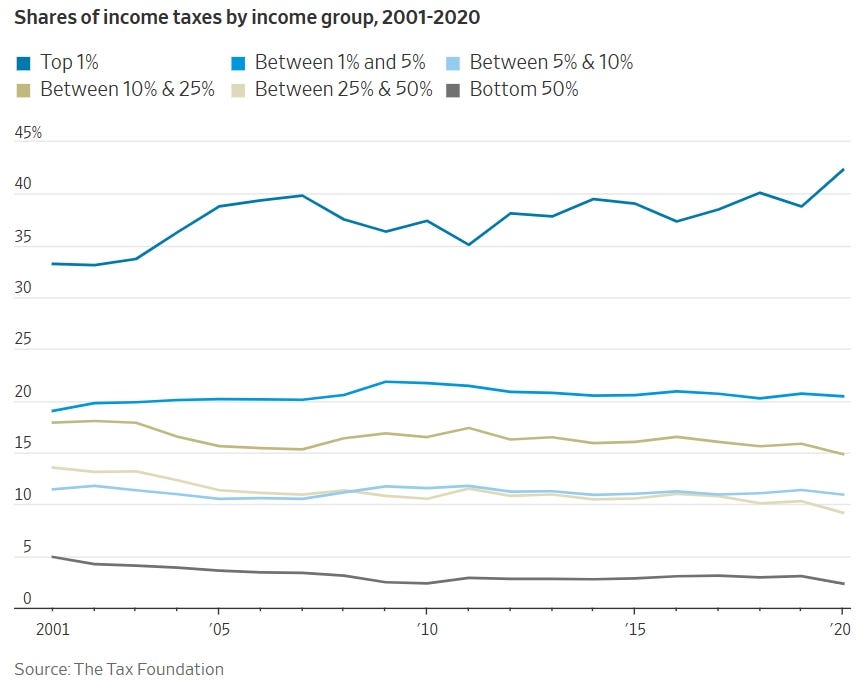

The Internal Revenue Service recently released its income and tax statistics for 2020, and they show the top 1% of earners paid 42.3% of the country’s income taxes. That’s a two-decade high in the share of taxes the 1% pay … The nearby bar chart is based on a Tax Foundation analysis of the IRS data for 2020. Note that the top 5% of earners reported 38.1% of total AGI [adjusted gross income] but paid 62.7% of all income taxes. The bottom 50% of earners reported 10.2% of AGI but paid 2.3% of all income taxes.

Mr. Biden likes to cherry pick the example of the odd billionaire who might pay a small amount of tax in a given year. But in the aggregate the top 1% in 2020 earned at least about $550,000 and paid an average income-tax rate of 26%. Those making more than $220,000 but less than $550,000 paid an average rate of 17.5%. For those in the next grouping, above about $150,000, it’s 13.1%. Above $85,000, 9.5%. Above $42,000, 6.5%. And the bottom 50% of taxpayers, those below about $42,000, paid an average rate of 3.1%. By the way, the trend over the past two decades is that the income tax burden has been shifting even more to the highest earners. The nearby line chart captures the trend. In 2001 the top 1% contributed 33.2% of income-tax revenue, nine points lower than in 2020. The Paul Ryan-Donald Trump tax reform in 2017 did little to change the trend despite Democratic claims that it favored the rich …

[I]ncome taxes contribute half of all federal revenue (and roughly another third is Social Security and Medicare, which are ostensibly “earned” benefits), so this gives a fair picture of the tax burden. The basic truth is that the rich really do pay their fair share and finance an enormous portion of the government.

So more government benefits programs lead to less work, fewer future workers, and the need for higher taxes on the increasingly diminishing future workforce, which will further deter work. It’s an upside-down Ponzi scheme run my government officials seeking votes. What could go wrong?

Paul, Marvelous as usual. How can the hosing (oops...meant housing but it was a typo that should stay) agencies get away with the communist "from each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs (as determined by some left wing bureaucrat)" dialectic/policy. Is it just lack of exposure? People should be incensed, Why aren't any politicians making this the big deal it should be?