A Federal Bureaucracy Beyond Even the President’s Control – Part 2

Federal bureaucracies are out of control because they’re out of the President’s control.

In the previous essay we explored why the Founders understood that presidents had to have the authority to hire and fire whom they wanted to serve them in the executive branch, if constitutional accountability was to be maintained. But that original understanding has long been replaced by a system in which executive branch employees are largely immunized from replacement at the elected president’s discretion. How that came to be is described by Gerald Frug in his law review article “Does the Constitution Prevent the Discharge of Civil Service Employees?”

Professor Frug relays some relevant subsequent history following Madison’s presidency as follows, showing how the once widely understood ability of presidents to remove anyone they wanted from the federal civil service broke down over time, to the detriment of constitutional government. His recounting of this history, largely forgotten today, is worth quoting at length:

[B]y 1828 the federal service had become unresponsive, inefficient, and filled with sinecures. Moreover, these employees represented an era not in keeping with the democratic spirit of the times: [as Carl Russell Fish writes in “The Civil Service and the Patronage,”] “When the people voted in 1828 that John Quincy Adams should leave office, they undoubtedly intended to vote that most of the civil servants should go with him.”

Efforts to revise the concept of property in office and to force government to be more responsive to the electorate preceded the election of 1828, beginning with the passage of the Tenure of Office Act of 1820. The Act established a fixed term of four years for a wide variety of federal offices and made clear that removals even within that term were at the pleasure of the President …

Madison thought that the Act was unconstitutional, considering it an impermissible congressional incursion into the presidential power to remove (or retain) employees. But efforts to curb the President’s removal power died in the House of Representatives.

[W]ith the election of the Republican Lincoln in 1860, the removals reached their peak: 1457 of the 1639 presidential appointees were replaced. The tradition of tenure had been replaced by a tradition of turnover. [My note: By the time Lincoln led the country through the Civil War, according to Michael Gerhardt in his book Lincoln’s Mentors: The Education of a Leader, “Lincoln … orchestrated the largest turnover in office of any president up until that time. He was convinced that his power to remove men not performing as he liked was his most important weapon for winning the war.”]

Efforts to create a permanent civil service system remained unsuccessful until after the assassination of President Garfield by a disappointed office seeker in 1881; the momentum created by the assassination contributed to the passage of the Pendleton Act of 1883.

The most striking fact about the Pendleton Act, however, was that it did not restrict the President’s general power to remove employees.

George William Curtis, the foremost advocate of civil service reform and the Chairman of Grant’s Civil Service Commission, argued: “Having annulled all reason for the improper exercise of the power of dismissal, we hold that it is better to take the risk of occasional injustice from passion and prejudice, which no law or regulation can control, than to seal up incompetency, negligence, insubordination, insolence, and every other mischief in the service, by requiring a virtual trial at law before an unfit or incapable clerk can be removed.”

The purpose of civil service reform was to limit the quadrennial turnover of government resulting from the spoils system; the reform movement did not otherwise seek to limit the President’s ability to remove employees he considered unfit. Even the Civil Service Commissioners had no term and could be removed by the President at will.

But beginning in 1887, the Commission sought a presidential order requiring that the reason for removal be specified and made part of the record of the department making the removal. Such a requirement, it thought, would further deter unjustified political removals. President Cleveland refused to issue such an order, but on July 27, 1897, President McKinley not only did so, but went further, directing that “[n]o removal shall be made from any position subject to competitive examination except for just cause and upon written charges filed with the head of the department or other appointing officer, and of which the accused shall have full notice and an opportunity to make defense.”

The Civil Service Commission did not intend that the addition to the civil service concept that removal be based on “cause” become a limit on the power of the executive to remove unqualified employees. Rather it saw the Executive Order as meaning merely that the executive had to have a legitimate, non-political reason for removal. The Commission recognized, however, that the provision could be interpreted to mean that a trial would be necessary to determine the existence of “cause.” The Commission opposed this interpretation, arguing that “to require this would not only involve enormous labor, but would give a permanence of tenure in the public service quite inconsistent with the efficiency of that service.” It therefore recommended to President Roosevelt, himself a former Civil Service Commissioner, that the rule be clarified. On May 29, 1902, Roosevelt issued a clarifying Executive Order: “Now, for the purpose of preventing all such misunderstandings and improper constructions of said section, it is hereby declared that the term ‘just cause,’ as used in section 8, Civil Service Rule II, is intended to mean any cause, other than one merely political or religious, which will promote the efficiency of the service; and nothing contained in said rule shall be construed to require the examination of witnesses or any trial or hearing except in the discretion of the officer making the removal.”

In its annual report of 1912, the Civil Service Commission explained why the Taft Executive Order continued to require only notice and a right to reply, and not a trial, prior to an employee removal: “The rules are not framed on a theory of life tenure, fixed permanence, nor vested right in office. It is recognized that subordination and discipline are essential, and that therefore dismissal for just cause shall be not unduly hampered. ... Appointing officers, therefore, are entirely free to make removals for any reasons relating to the interests of good administration, and they are made the final judges of the sufficiency of the reasons …”

Shortly after Taft issued his Executive Order, Congress began to debate a rider to the Post Office appropriations bill of 1912, which, in part, gave statutory authority to the provisions of the Executive Order and was phrased in almost identical words. The final bill, known as the Lloyd-LaFollette Act, was enacted and signed into law on August 24, 1912. This codification of President Taft’s Executive Order remains today the governing statute for all removals of employees from the federal civil service except those of veterans. Nothing in the legislative history of the Lloyd-LaFollette Act questioned the unwillingness reflected in the Executive Order to require the executive to “prove” he had cause prior to discharging a civil servant. Indeed, the Act’s adoption of the language of prior Executive Orders specifying that no hearing would be required, thus limiting the employee’s rights to notice and a right to a reply, indicates quite the contrary. Civil service rules, therefore, continued to prohibit only certain impermissible grounds for removal and otherwise allowed the executive to define “cause.” The legislative and executive branches continued to affirm the importance of executive discretion as established by the Decision of 1789, a joint position broken only by the constitutional crisis over the Tenure of Office Act of 1867.

Beginning in the early 1930’s, however, the Civil Service Commission began to seek a role in reviewing the discretion exercised by the agencies in employee dismissals and urged the creation of an appellate process within the Civil Service Commission. No action was taken on this proposal until the passage of the Veterans’ Preference Act of 1944. Section 14 of the Act provided veterans thirty days’ notice of any adverse action against them; afforded them the right of a personal appearance to challenge the action, rather than merely a right to a written reply as under the Lloyd-LaFollette Act of 1912; and, most importantly, afforded veterans the right to appeal to the Civil Service Commission “from an adverse decision ... of an administrative authority ....” The genesis of this dramatic departure from the historic emphasis on executive discretion is obscure. The House report on the bill and the very brief House debate focused solely on the wartime concern with providing adequate employment opportunities for returning veterans and did not explain the need for the procedural changes made by Section 14. There was no Senate debate on the bill. Section 14 might be explained, however, simply by the Act’s pervasive emphasis on giving veterans a decisive break in employment opportunities, a break which was too important to be entrusted to executive discretion …

Once the veterans’ rights to an appellate process were established, however, there seemed to be an incongruity between having a review process for removal of veterans, who constituted more than fifty percent of the federal civil service, and having no review process for the remaining federal employees. Some called for the establishment of a single federal procedure by extending the principles of the Veterans’ Preference Act of 1944 to all civil service employees, but others preferred making the Lloyd-LaFollette Act procedures universally applicable. Thus, in its review of needed reforms in the organization of the federal government, the second Hoover Commission called for a return to the provisions of the Lloyd-LaFollette Act of 1912, criticizing the procedures under section 14 of the Veterans’ Preference Act. That section, said the Commission, “creates serious problems for management, unduly hampers operations, and ... produce[s] quite the opposite of good employer-employee relationships.”

Shortly after assuming office, President Kennedy appointed a task force to establish a policy for employee-management cooperation in the federal service which would deal with a number of problems of federal government employees, including the right to appellate review of adverse actions. The committee recommended that the President extend the Veterans’ Preference Act rights to all civil service employees. On January 17, 1962, President Kennedy issued an Executive Order establishing a system of appeals within each agency for review of adverse actions and requiring that the appellate process provide a hearing to the employee. President Nixon supplemented this procedure with a right to appeal to the Civil Service Commission itself, thereby giving non-veterans the same rights veterans had under the Veterans’ Preference Act. On June 11, 1974, President Nixon made appeal to the Civil Service Commission the sole possible appeal, revoking the agency review process established by President Kennedy. The right of every civil servant to an outside appraisal of the grounds for dismissal has thus recently replaced the historic emphasis on executive discretion.

In 1926, the Supreme Court was squarely faced with the question it sought to avoid in Parsons and Shurtleff: Was the Decision of 1789 giving the President the sole power to remove his appointees merely a matter of legislative choice by the First Congress, subject to reversal by a later Congress, or was it constitutionally compelled? In Myers v. United States, a postmaster, removed from office by action of the Postmaster General, sued for his salary from the date of his removal. He argued that his removal was illegal under the 1876 Act creating his office, which provided that he could be appointed and removed only “by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.” The Court rejected the postmaster’s argument, holding that the sole executive power of removal could not be limited by Congress.

The opinion, written by Chief Justice (and former President) Taft, relied heavily on Madison’s arguments for presidential authority to remove made at the time of the Decision of 1789. The power of removal, the Court reasoned, was inherently an executive power, not a legislative or judicial function. The Constitution by its terms limits the requirement of Senate concurrence to appointments, because a limitation on removals would be a much greater restriction on presidential power. The rejection of a nominee enables the Senate to prevent the appointment of a bad person to government and limits the President only by forcing him to select another person entirely of his own choosing. On the other hand, a Senate rejection of an attempted removal would force the President to retain a person not of his own choosing. The Constitution was not designed to give Congress the power, in the case of a political difference with the President, to thwart his authority “by fastening upon him, as subordinate executive officers, men who by their inefficient service under him, by their lack of loyalty to the service, or by their different views of policy, might make his taking care that the laws be faithfully executed most difficult or impossible.” [As the Supreme Court’s opinion stated:] “The power to prevent the removal of an officer who has served under the President is different from the authority to consent to or reject his appointment. When a nomination is made, it may be presumed that the Senate is, or may become, as well advised as to the fitness of the nominee as the President, but in the nature of things the defects in ability or intelligence or loyalty in the administration of the laws of one who has served as an officer under the President, are facts to which the President, or his trusted subordinates, must be better informed than the Senate, and the power to remove him may, therefore, be regarded as confined, for very sound and practical reasons, to the governmental authority which has administrative control. The power of removal is incident to the power of appointment, not to the power of advising and consenting to appointment, and when the grant of the executive power is enforced by the express mandate to take care that the laws be faithfully executed, it emphasizes the necessity for including within the executive power as conferred the exclusive power of removal.” [272 U.S. 52, 121-22 (1926).]

The Court concluded that the congressional attempt to require Senate concurrence in the removal of postmasters, like the broader attempt to limit the President’s removal power by the Tenure of Office Act of 1867, was unconstitutional.

Nevertheless, in more recent years federal civil service employees have been granted extensive protections from removal, contrary to the president’s constitutional duty.

On this subject, it’s interesting to note the views of the first female Cabinet Secretary and the chief architect of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation, Frances Perkins, who was subsequently made a Commissioner on the Civil Service Commission in 1946. Regarding her feelings on the importance of filling the federal bureaucracy with proper professionals, according to her biographer in The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR’s Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience, “Frances [quoted] Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, whom she had long revered, [who] said that although a person may have a constitutional right to his beliefs, he has no constitutional right to be a government official. In other words, with so many people wanting federal jobs, why accept or employ people who might prove problematic?”

Very little quantitative research has been done to examine the consequences of modern presidents’ ability to hire and fire their own executive branch employees at will, but business professors at Northwestern and Berkeley have done some work on the issue. They found that most federal civil service employees are Democrats and that, when the President is a Republican, great inefficiencies (amounting to an 8 percent increase in cost overruns) are created when civil services employees don’t share the President’s understanding of their mission. As the researchers write:

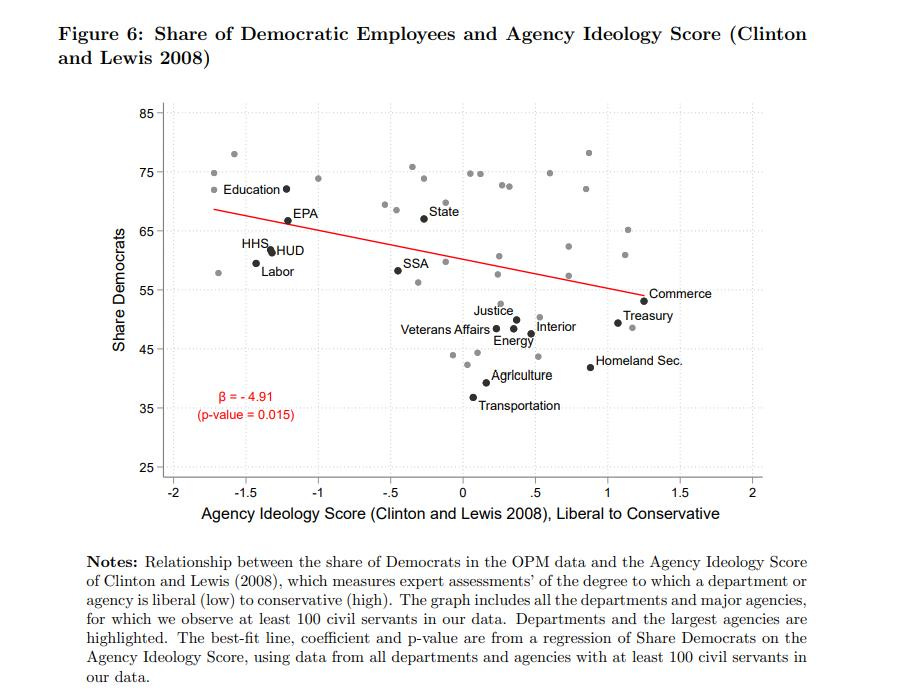

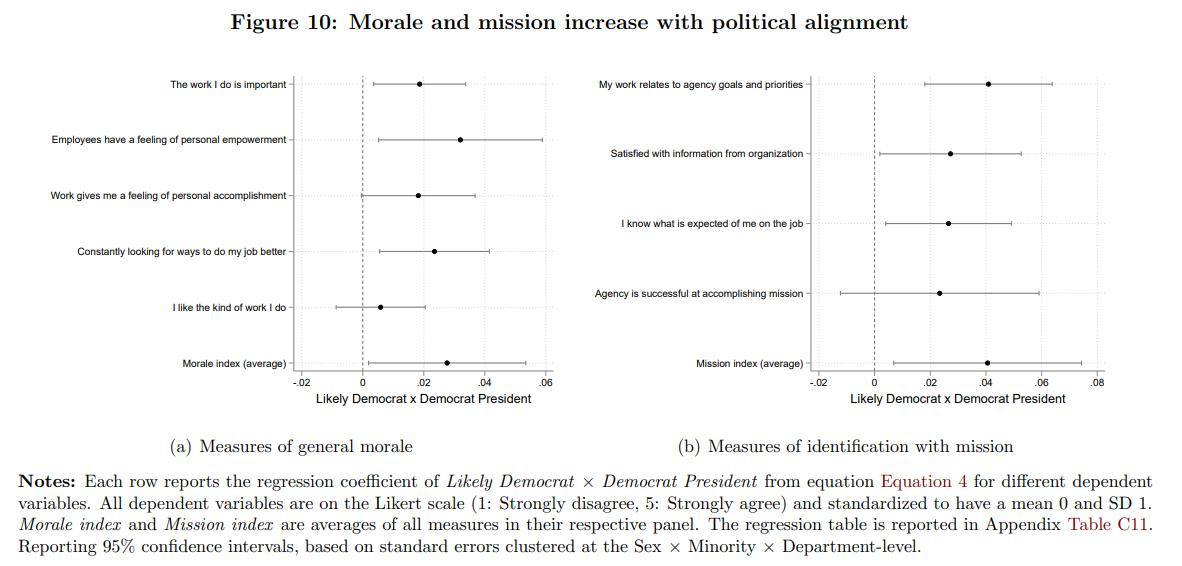

While mission can act as a powerful intrinsic motivator, it may also create frictions when the preferences of leaders and their subordinates become misaligned … Frictions of this kind may be particularly relevant in bureaucracies, whose mission can change from one day to the next due to political turnover. When politicians face a large share of subordinates who no longer agree with the new priorities of the organization and whose compensation is not directly tied to performance, their real authority as the principal can be severely limited … In this paper, we turn to the U.S. federal government to investigate the role of alignment within organizations. We examine how the personnel policies and performance of the organization are affected by ideological (mis)alignment between bureaucrats and their political leaders (i.e., agents and their principals) … Our study draws on a large, novel data set that contains information on the partisan leanings of U.S. bureaucrats. We link personnel records for the near-universe of federal employees between 1997–2019 with contemporary administrative data on all registered voters in the United States. By combining both sources of information, we are the first to measure ideology—and thus political alignment—for more than a million individuals throughout nearly the entire federal bureaucracy … [W]e document a remarkable degree of political insulation among career civil servants. In sharp contrast to our results for political appointees, we observe virtually no political cycles in the career civil service. In our data, the share of Democrats remains nearly constant over the entire time period … Democrats make up the plurality of career civil servants. The share of Democrats hovers around 50% across the 1997–2019 period, while the share of Republicans ranges from 32% in 1997 to 26% in 2019. This overrepresentation is present in nearly every department. The share of Democrats is highest in the Department of Education, the State Department, and the EPA. The most conservative departments are Agriculture and Transportation, where the shares of Democrats and Republicans are nearly equal. Democrats are especially over-represented in more-senior positions … Broadly summarizing, although politicians exert significant control over the ideological makeup of the highest layers of the federal bureaucracy, there are virtually no political cycles among rank-and-file civil servants. This leads to large and temporarily persistent ideological misalignments within the executive branch, irrespective of which party controls the White House. Given that Democrats are overrepresented among career bureaucrats, however, ideological misalignments are especially prevalent under Republican presidents … Our analysis focuses on services and works contracts, which require significant monitoring and exhibit substantial variation in cost overruns and delays. Relying on “within-officer” variation to compare contract outcomes in years in which the officer is and is not aligned with the political superiors, we find that misalignment increases cost overruns by approximately 1% of initial contract value—about 8% relative to the mean overrun. This result holds even when comparing procurement officers working in the same department and year … While the insulation of the career civil service prevents political interference, civil servants may have their own preferences and ideological leanings, which can conflict with those of the president … To shed light on the costs of such misalignment, we focus on a subset of civil servants who work across all departments of the government and for whom we can measure performance: procurement officers. Linking procurement contracts to the matched personnel and voter registration data allows us to study the mission-alignment of procurement officers across nearly all departments of the federal bureaucracy. Strikingly, we find that political misalignment increases cost overruns by 8%. We provide evidence that suggests that a general “morale effect” is an important mechanism behind this finding, whereby bureaucrats who are ideologically misaligned with the organizational mission have lower motivation. As political turnover leads to sizable mission-misalignment between politicians and civil servants, our findings provide direct evidence on the costs of political insulation of the bureaucracy, which should be traded off against the benefits of avoiding political interference.

Because there’s been such limited research in this area, several of these researchers’ charts and graphs showing the extent and impact of one party’s dominance over the federal bureaucracy are set out below.

A March, 20205, survey conducted of Federal Government Managers, defined as those working for the federal government or federal government agencies and having household incomes of more than $75,000 annually, and living in the National Capitol Region (the D.C. metro area), asked "Suppose that President Trump gave an order that was legal but you believed was bad policy. Would you follow the president's order or do what you thought was best?" and 75% of such managers who voted for Democratic Presidential candidate Kamala Harris (Trump’s opponent in the 2024 presidential election) said they would “do what I thought was best" rather than follow Trump’s order.”

In the next series of essays, I’ll set out some thoughts on potential reforms that would help rein in the largely unchecked power currently held by today’s federal bureaucracy.