Where Did the Racial Boxes People Check on Forms Come From? – Part 3

The very, very strange case of the “Hispanics” category.

David Bernstein, in his book Classified: The Untold Story of Racial Classifications in America, describes the long, sordid history behind America’s current, arbitrary racial classification system. In this essay, we’ll explore Bernstein’s recounting of the particularly arbitrary “Hispanic” category.

As Bernstein writes:

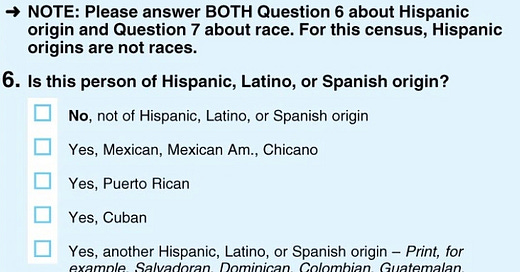

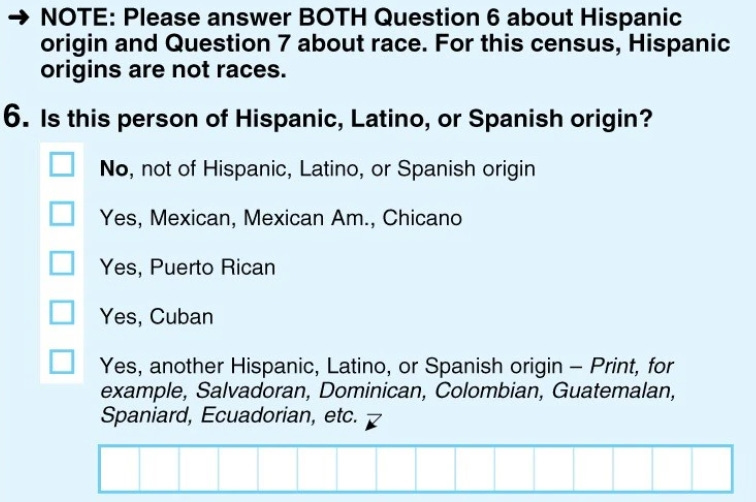

Unlike the other minority classifications, Directive 15 defined Hispanic as an ethnicity, not a race. Nevertheless, for many Americans Hispanic identity implies something akin to racial traits. Geoffrey Fox, author of Hispanic Nation, points out that Americans often say someone “looks Hispanic.” They usually mean “someone who is too dark to be white, too light to be black, and has no easily identifiable Asian traits.” The legal definition of Hispanic, however, does not address appearance. Rather, Hispanic is defined as a person of “Spanish origin or culture.” Most Hispanics in the United States are primarily of mixed European and indigenous ancestry, but Hispanics may be of any combination of African, Asian, European, and indigenous descent. It follows that a Hispanic person need not have a certain “look.” … The Hispanic category also includes people whose ancestors’ first language was not Spanish and who may have never spoken Spanish. This includes immigrants from Spain and their descendants whose ancestral language is Basque or Catalan. It also includes indigenous immigrants from Latin America whose first language is not Spanish, whose surnames are not Spanish, and whose ethnic and cultural backgrounds are not Spanish. Americans of Portuguese or Brazilian ancestry are sometimes defined as Hispanic by government fiat. Notably, only 2 percent of Portuguese and Brazilian Americans consider themselves Hispanic … The Hispanic label, Professor Martha Gimenez argues, “fulfills primarily ideological and political functions…it identifies neither an ethnic group nor a minority group.” Another label, “Latino,” eventually became a government-endorsed official alternative to Hispanic. In other words, the official federal classification is now “Hispanic or Latino.” The definition of the category—of Spanish-speaking origin or culture—has remained the same. The term Latino attracts similar criticism as Hispanic. The Latino category is “artificial” and “preposterous,” argues Michael Lind of the New America Foundation. It “include[s] blond, blue-eyed South Americans of German descent as well as Mexican-American mestizos and Puerto Ricans of predominantly African descent.” Meanwhile, many American Hispanics do not consider themselves to be part of a minority group, much less a racial minority group. Slightly more than half of Americans of Spanish-speaking descent identify as white. Among Latinos, this ranges from 82 percent among Cubans to 22 percent among Dominicans … In short, the Hispanic population is heterogeneous on a variety of metrics. That said, the Hispanic and Latino labels caught on quickly. Spanish-language media executives who were eager to create a national media market for Spanish content encouraged Hispanic pan-ethnic identity. Political activists found that these pan-national categories create the sense of a large, homogenous, politically powerful group … Nevertheless, Americans of Spanish-speaking ancestry still overwhelmingly prefer to be labeled by their country of origin or “just American” rather than as Hispanic or Latino. Most accept Hispanic or Latino as a secondary identity, though Americans with only partial Hispanic ancestry often reject those labels. Almost no one prefers Latinx, the gender-neutral alternative recently promoted by left-leaning activists.

As a side note, regarding the bizarre phrase “Latinx,” Sophie Yarin writes:

It seems like there’s a new word for Latin American heritage every couple of decades—and it never seems to fit just right. “Hispanic” was brought into common parlance in the early 1970s, but was later challenged by “Latino” and its feminine partner “Latina.” Now comes the rise of the divisive—but gender-neutral—“Latinx,” touted by progressives for its supposed modern hipness, yet somewhat reviled by the people it represents … While there’s no one group or individual responsible for coining Latinx, its popularity has snowballed in tandem with conversations around gender. Previous terminology forced the speaker to identify as male or female, Latino or Latina, while Latinx gives both speaker and listener the ability to opt out of the gender binary. The term was embraced enthusiastically by progressive entities with a stake in gender-neutral policies … According to the Pew Research Center, a thimble-sized portion of people with Latin American ancestry use the term Latinx. In August 2020, the center reported that 3 percent of respondents viewed it favorably; a year later, a Gallup poll increased that to 4 percent.

As explained in Chapter 3 of a podcast called The Witch Trials of J.K. Rowling (at the 45:00-minute mark), the phrase originated on a social media site Tumblr:

“So, a good example of this [phrases migrating from the social media site Tumblr to more mainstream outlets] is the word Latinx, right. If you look at early articles about the word Latinx, these are articles that are coming out between 2013 and 2015, a lot of them reference Tumblr. Gabby Riviera of Autostraddle wrote ‘The word Latinx has been appearing on my Tumblr dashboard for the last year.’ The website Latino Rebels also ran an article about the term and they were like ‘This word comes from Tumblr, and we don’t like it, it’s from the American blogosphere and nobody in Latin America uses it.’”

The phrase, while widely used on the political left, it is so unpopular with Hispanics that, as reported by the Associated Press:

A group of Hispanic lawmakers in Connecticut has proposed that the state follow Arkansas’ lead and ban the term “Latinx” from official government documents, calling it offensive to Spanish speakers. The word is used as a gender-neutral alternative to “Latino” and “Latina” and is helpful in supporting people who do not identify as either male or female, according to the word’s backers. But state Rep. Geraldo Reyes Jr. of Waterbury, the bill’s chief sponsor and one of five Hispanic Democrats who put their names on the legislation, said Latinx is not a Spanish word but is rather a “woke” term that is offensive to Connecticut’s large Puerto Rican population … The League of United Latin American Citizens, the oldest Latino civil rights group in the U.S., announced in 2021 that it would no longer use the term Latinx. “The Spanish language, which is centuries old, defaults to Latino for everybody,” Reyes said. “It’s all-inclusive. They didn’t need to create a word, it already exists.”

Anyway, back to Bernstein:

Meanwhile, the scope of the Hispanic category remains contested. Some Chicano activists of mixed-race ancestry, for example, argue that fair-skinned immigrants from Mexico’s European-descended elite should not be eligible for affirmative preferences for Hispanics. These preferences are intended, in their view, for nonwhite minorities, not for Hispanics who were considered white in their home countries. Other Hispanic activists resent that Cuban Americans, who overwhelmingly identify as white and on average are more politically conservative than other Hispanic groups, share their minority classification. And many Latinos think that immigrants of Spain and their descendants should be classified with other white Americans of European descent, not as Hispanic/Latino. Political and cultural elites, however, often behave as if Hispanics are a homogenous population. For example, the producers of the recent West Side Story movie committed to ensuring that the movie is culturally sensitive in depicting the members of the Puerto Rican gang “The Sharks” and their families. The producers proudly announced that “Hispanic actress Rachel Zegler” would play the role of Maria. Zegler grew up in New Jersey and has one parent of Colombian descent, one of European descent, and (obviously) none of Puerto Rican descent. Exactly how casting a half-Colombian, half-European actress to play a Puerto Rican character is culturally sensitive was left unexplained … Even though most Hispanics identify as white on the census and in surveys, they are often referred to as “people of color,” that is, nonwhites … As noted previously, when the Office of Management and Budget created the official Directive 15 categories in 1977, it dictated that Hispanic was an ethnic classification, not a racial one. Government agencies that collected racial and ethnic statistics mostly responded by placing a two-part race/ethnicity question on demographic forms. These forms asked individuals if they were Hispanic and what race they belonged to. The Department of Education, however, demurred. Its Office of Civil Rights (OCR) requires almost all schools in the United States, from elementary to graduate school, to gather demographic statistics on matriculants. OCR left it up to the schools and universities gathering those statistics to decide whether to use a two-part question or a one-part question. A one-part question asks individuals whether they are Black, White, Hispanic, Native American, or Asian. Universities overwhelmingly chose the one-question route. This made Hispanic status the equivalent of a racial status -- for example, one could not be both Hispanic and White on these universities’ admissions forms. The Department of Education did not change its rules to require a two-question ethnicity classification until 2007. By then, the notion that Hispanic affirmative action preferences in university admissions amounted to a “racial” preference was entrenched … The notion that Hispanic/Latino is a racial category has found its way into Supreme Court opinions. Justice Sotomayor, for example, has argued that affirmative action for African Americans and Hispanics is necessary because “race matters.” This implies that Hispanics are a racial minority. Supreme Court decisions more generally treat affirmative action preferences for Hispanics as racial preferences. Other parts of the federal government also describe Hispanics as members of a racial minority. For example, the SBA’s guidance on disadvantaged business enterprises still depicts Hispanic as a racial category. Notwithstanding the frequent racialization of Hispanicness, the federal government’s statistical rules, including those used by the Census Bureau, define Hispanic as an ethnic, not racial, classification. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Census Bureau proposed making “Hispanic” a racial category akin to “Black” or “White.” Most major Latino organizations aggressively opposed the change. Census Bureau employees specializing in racial demography also strongly opposed categorizing Hispanic as a racial identity. Their opposition reflected deference to civil rights and ethnic identity organizations. These groups worried that creating a Hispanic racial category would reduce their groups’ reported populations and therefore their political clout. African American groups feared that Afro-Latinos would identify as Hispanic, not Black; American Indian organizations were concerned that some individuals of indigenous heritage would identify as Hispanic, not Native American; and Asian American activists worried that some Filipinos would identify as Hispanic and not Asian. The bureau ultimately shelved the proposal.

Bernstein then turns to the question as to why Hispanics came to be classified as an “ethnic” group rather than a “racial” group:

All of this raises the question of how Hispanics -- unlike many other relatively dark-complexioned groups -- came to be classified as members of an ethnic minority group distinct from non-Hispanic whites. Historically, the US government classified Hispanics as white. The Census Bureau presumptively classified Hispanics as white except in 1930, when the Census included a racial category for Mexicans. From 1940 until 1970, census takers were instructed to either rely on Mexican Americans’ racial self-identification or to classify them as white unless they obviously appeared to belong to another race … The most influential Mexican American group, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), lobbied to have Mexican Americans classified as whites in government data collection, especially by the Census Bureau. Other Mexican American leaders insisted that their constituents were white, just like Italians, Irish, and other Catholic ethnic groups. By the 1950s, however, LULAC and other Mexican American lobbying groups changed course. They worked with Mexican American legislators to urge that a Mexican American category be listed on forms filled out by government contracting firms to show that they met antidiscrimination requirements. The lobbying groups asserted that Mexican Americans had brown skin and mixed-race heritage. They therefore experienced a level of racial discrimination akin to what African Americans faced. In response, the government added a “Spanish-Americans” category to the main form but as an ethnic rather than a racial category … Mexican American activists in the late 1960s pressured US census officials to create a category for Spanish speakers and their descendants. The officials declined to do so. Some found the category too diverse to be useful; others thought of Hispanics as a white ethnic group that would eventually assimilate into the broader white population. The Census Bureau classified Hispanics as generically white in the 1970 census. This decision met with strong criticism from Latino civil rights organizations. Their leaders believed that better data collection on the Spanish- origin population was crucial to persuading the civil rights bureaucracy to pay more attention to discrimination against Hispanics. The Nixon administration responded by adding a question about “Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central or South American, [or] Other Spanish” origin or descent to the detailed census questionnaire sent to 5 percent of American households … Nixon, “the Dark Father of Hispanicity,” also pushed for the government to develop a pan-ethnic category for people with Spanish-speaking ancestors. If people came to identify with such a category, Nixon thought, the influence of radical Mexican American and Puerto Rican activists would wane. Nixon insisted that Cuban Americans be included in this new classification … Some Mexican American activists objected to the notion of a new pan-ethnic classification for descendants of Spanish-speakers. Most activists, however, decided it would be politically beneficial to recast the Mexican-specific Chicano movement as a pan-ethnic movement that included all Latinos. This would allow activists to expand their political base from the Southwest to Florida and the Northeast … [H]ow [did] “Hispanic” became the official classification for those of Spanish-speaking heritage [?] In 1976, President Ford signed legislation requiring the federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to “develop a government-wide program for the collection of data with respect to Americans of Spanish origin or descent.” The legislation had been sponsored by Congressman Ed Roybal, a strong advocate for Mexican American interests. A year later, OMB adopted “Hispanic” as the official category for government record-keeping in 1977 as part of its Statistical Directive No. 15. A task force of three federal employees with Spanish-speaking ancestry -- a Mexican American, a Puerto Rican, and a Cuban American -- had met for six months to hammer out the Hispanic category and its scope … The committee ultimately, but grudgingly, agreed on Hispanic. According to Noboa-Rios, “There was never any consensus in that group to the very end.” … [T]he broad Directive 15 “Hispanic” category, however, encompassed many people who identified, and were identified by others, as white. Combined with the new norm of self-identification, this meant that the category would include many people with light complexions and predominately or entirely European ancestry … Despite these various objections, the Hispanic category soon dominated government nomenclature for people of Spanish-speaking descent. By 1993, for example, every state used this category when reporting the race and ethnicity of newborns … Part of the reason that Hispanic became the dominant term to describe people of Spanish-speaking heritage is that the US Census adopted it as an ethnic category in 1980. The adoption was the product of a vigorous lobbying campaign by Latino organizations. Professional demographers denounced the addition of the Hispanic category as a product of political interference with the Census Bureau. But Vilma S. Martinez, head of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund and chairman of a special census advisory committee on Spanish population, was unapologetic about lobbying for a Hispanic census category. She told the New York Times, “We are trying to get our just share of political influence and Federal funds. There’s nothing sinister about it.”

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine how white ethnic groups and black immigrants are treated under America’s racial classification systems.

Paul, if you did not write this stuff, I would never believe it were true. OMG. Thanks.