Where Did the Racial Boxes People Check on Forms Come From? – Part 5

How are children of multi-racial parents classified?

David Bernstein, in his book Classified: The Untold Story of Racial Classifications in America, describes the long, sordid history behind America’s current, arbitrary racial classification system. In this essay, we’ll explore Bernstein’s recounting of how children of multi-racial parents came to be automatically designated as “minority.” As Bernstein writes, regarding people with multi-racial backgrounds:

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a grassroots movement of interracial couples and the children of such couples arose. Activists began to lobby for adding a multiracial category to government forms, including the census. The activists argued that the government should allow Americans to adopt classifications reflecting the full panoply of identity. Requiring mixed-race children to check only one box, multiracial activists contended, forced them to implicitly reject one of their parents … Limiting people to one racial box also reinforced the racist “one-drop” notion that if a person has mixed racial ancestry, only one’s minority ancestry “counts.” Recognizing a multiracial American category, by contrast, would help counter racial antagonism and separatism … Nevertheless, African American civil rights groups and their allies in the federal government expressed strong and sustained opposition to recognizing a multiracial category. They feared that because many African Americans have known white ancestry, providing a multiracial option might reduce the number of people identifying as black on government forms. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has noted, almost all African Americans not of recent immigrant origin “are genetically mixed, the only question is how much?” … Minority activists worried that official adoption of a multiracial category would discourage multiracial individuals from identifying with their minority racial heritage. This would, in turn, make them less likely to be involved in racial equity campaigns … OMB, beholden to President Bill Clinton, a Democrat, chose a compromise. Instead of recognizing a multiracial classification, OMB ordered federal agencies to allow people to check off more than one race box. That order halted the multiracial movement’s momentum, and the movement soon ceased to be a political force. Meanwhile, civil rights groups and ethnic organizations expressed concern that double-box checkers would reduce minority groups’ reported numbers. OMB responded to this concern by ordering agencies to allocate people who identify as white and a minority race “to the minority race.” OMB told civil rights enforcement agencies that if someone identified as two minority races, the agencies should allocate the person to whichever ethnicity would be more useful to a discrimination claim.

The potential for confusion created by that odd official default to a classification for a multi-racial person as “minority” is explored by Richard Alba in his book The Great Demographic Illusion: Majority, Minority, and the Expanding American Mainstream. As Alba writes:

Many Americans believe that their society is on the precipice of a momentous transformation, brought about by the inevitable demographic slide of the white population into numerical minority status and the consequent ascent of a new majority made up of nonwhites … It is in fact rare for demographic data to receive so much public attention. Announcements by the Census Bureau, such as the 2015 press release reporting that the majority of children under the age of five are no longer white (according, I have to add, to the narrow definition of “white” employed by the census), receive wide publicity and are greeted with headlines such as “It’s Official: The US Is Becoming a Minority- Majority Nation” (this one in US News & World Report) … Yet there are powerful reasons to be skeptical about this demographic imagining of the present and the near future: it assumes a rigidity to racial and ethnic boundaries that has not been characteristic of the American experience with immigration … The rigidity of ethno- racial lines is already being challenged by a robust development that is largely unheralded: a surge in the number of young Americans who come from mixed majority- minority families and have one white parent and one nonwhite or Hispanic parent. Today more than 10 percent of all babies born in the United States are of such mixed parentage; this proportion is well above the number of Asian- only children and not far below the number of black- only infants. This surge is a by- product of a rapid rise in the extent of ethno- racial mixing in families. What makes this phenomenon new is the social recognition now accorded to mixed ethno- racial origins as an independent status, rather than one that must be amalgamated to one group or another … But the bottom line is this: for the critical public presentations of data, the Census Bureau classifies individuals who are reported as having both white and nonwhite ancestries as not white; my analyses for the book show that the great majority of all mixed Americans are therefore added to the minority side of the ledger. This classification decision has a profound effect on public perceptions of demographic change, but it does not correspond with the social realities of the lives of most mixed individuals, who are integrated with whites at least as much as with minorities. The census data thus distort contemporary ethno- racial changes by accelerating the decline of the white population and presenting as certain something that is no more than speculative— a future situation when the summed counts of the American Indian, Asian, black, and Latino categories exceed the count of whites … The narrative most widely believed about the immigration past, overwhelmingly European in origin, is that the descendants of the immigrants were absorbed into the mainstream society, despite initial experiences of exclusion, discrimination, and denigration for alleged inferiority. This is an assimilation story. That narrative now collides with the perception, nourished by the majority-minority concept, of a stark and deep-seated cleavage between the currently dominant white majority and nonwhite minorities. That perception feeds a different narrative: that a contest along ethno-racial lines for social power (taking that term in its broadest sense) is intensifying.

But is that true? Likely not. As Alba explains:

I show evidence that individuals with black and white parentage have a very different experience from other mixed persons and identify more strongly with the minority side of their backgrounds. However, many other mixed majority-minority Americans have everyday experiences, socioeconomic locations, social affiliations, and identities that do not resemble those of minorities. On the whole, these individuals occupy a liminal “in between,” but their social mobility and social integration with whites are indicative of an assimilation trajectory into the societal mainstream … We should understand the assimilation of today therefore as neither inherently excluding the descendants of the newest immigrants because they cannot become white nor requiring them to present themselves as if they were white. Instead, the mainstream can expand to accept a visible degree of racial diversity, as long as the shared understandings between individuals with different ethno-racial backgrounds are sufficient to allow them to interact comfortably. In this way, increasing participation in the mainstream society is associated with “decategorization,” in the sense that the relationships among individuals in the mainstream are not primarily determined by categorical differences in ethno- racial membership. In colloquial terms, they treat each other by and large as individuals rather than as members of distinct ethno- racial groups. My argument is that, for the most part, the new, or twenty-first-century, phenomenon of mixed minority-majority backgrounds is a sign of growing integration into the mainstream by substantial portions of the new immigrant groups, especially individuals with Asian and Hispanic origins. The mainstream integration of mixed individuals is signaled by such indicators as their high rates of marriage to whites. But of course, it is not simply the children from mixed families who are integrating; many of the nonwhite parents are doing so as well, and as will be shown, they are often settling with their families in integrated neighborhoods, where many whites are also present. The mainstream does appear to be expanding and becoming more diverse, and the implications are potentially quite consequential … The argument of this book is not that whites will retain a numerical majority status, although I do not rule out such a possibility, but rather that mainstream expansion, which would meld many whites, nonwhites, and Hispanics, holds out the prospect of a new kind of societal majority … I show, for example, that the group with mixed minority-white parentage is the pivot on which the outcomes of Census Bureau population projections depend; if we change our assumptions about its classification, the projected future looks quite different.

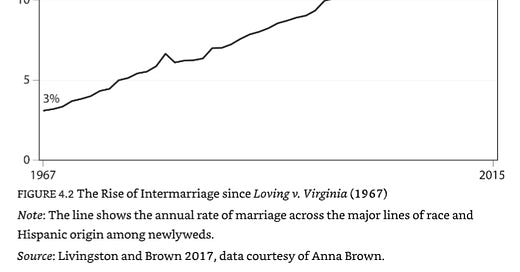

Alba charts the remarkable rise in inter-racial marriages since the Supreme Court struck down prohibitions of inter-racial marriages as unconstitutional in the 1967 case of Loving v. Virginia. As Alba writes:

Since [1967], the rate of intermarriage has climbed steadily. This is not to say that marriage is the only route to family mixing; mixed families are also forming and procreating without a legal bond. But the best trend data are for marriage, and there is no reason to suspect that the mixing to be seen in marriage is not also occurring in the families of unmarried partners. In fact, the degree of mixing outside of marriage may be even greater, since some mixed couples who anticipate family resistance may hesitate to marry. Figure 4.2 shows the trend line of the percentage of ethno- racial intermarriages that took place each year between 1967 and 2015, as calculated by the Pew Research Center.

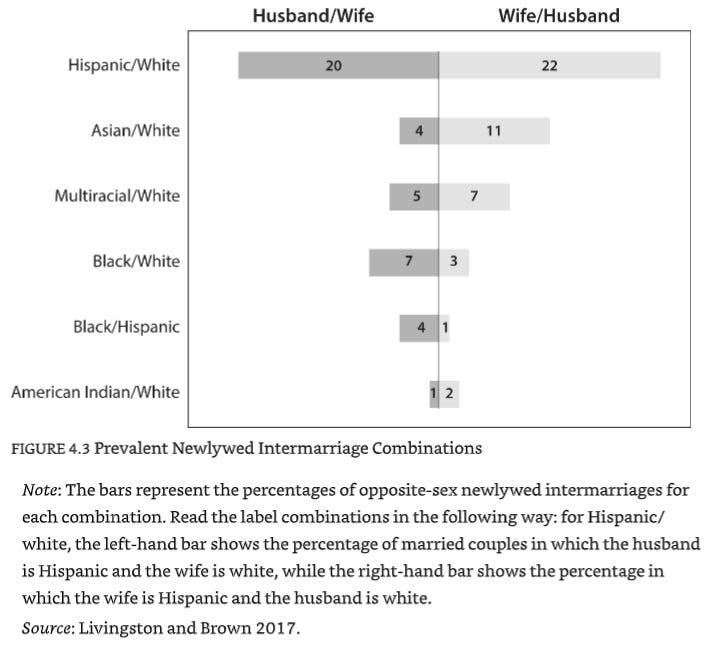

When Loving v. Virginia was decided, that rate was quite low— just 3 percent of newlyweds married someone from a different ethno- racial background. But the percentage has increased almost in a straight line since 1967 and in 2015 stood at 17 percent, with no hint of stopping. Recently, one of every six newlyweds was intermarrying. This is what demographers call an “incidence” rate. The impact on the “stock” of existing marriages is necessarily slower, since most of those marriages occurred in years when the intermarriage rate was lower than it is now. Nevertheless, today 10 percent of all married persons have a partner of a different race or ethnicity from their own. The predominant form of intermarriage unites minority and white partners. Marriages between Hispanics and non- Hispanic whites make up more than 40 percent of all recent intermarriages (see figure 4.3). Marriages between whites and Asians are the next most common combination, at 15 percent. Altogether, intermarriages with one non- Hispanic white partner constitute more than 80 percent of the whole.

As Alba writes:

[A]ssimilation involves “decategorization”: individuals coming originally from different sides of an ethno- racial boundary— one majority, one minority— no longer commonly think about each other, or treat each other, based on their category memberships but as individuals. Because this definition is agnostic about how the perceived similarity between individuals on the two sides of a boundary grows, it allows for similarity arising because of changes that take place on both sides as a result of mutual influence. It also indicates that assimilation is a matter of degree, not an all- or- nothing proposition. Assimilation can be significant without eradicating the ethno- racial differences and distinctions between the two sides, though it does entail the decline of their social significance … Neo-assimilation theory points to a number of mechanisms that promote assimilation for a substantial portion of minority groups. The single most important is the intersection of the aspirations of many minority group members with the social structures through which they can realize them. The theory posits, in other words, that most individuals of whatever origins seek to improve their lives materially and socially. They pursue practical strategies in search of a better job, a better place to live, and interesting social milieus— social mobility, in the broadest sense of the term … A common misconception associated with the majority-minority idea is that whites will soon be a minority of voters, or even citizens. New York Times columnist Charles Blow, for instance, declared in a 2018 op-ed on “white extinction anxiety” that “white people have been the majority of people considered United States citizens since this country was founded, but that period is rapidly drawing to a close.” He cites census data and projections, but in fact that evidence does not support his conclusion about citizens. The census numbers in principle include all residents of the United States. That includes many foreign- born noncitizens, such as legal permanent residents, even some who reside temporarily in the United States (but not tourists and others whose presence is transient). And it appears that many undocumented residents fill out the census form, as government agencies encourage them to do. The Census Bureau population projections indicating whites as a numerical minority by midcentury also show a rising percentage of foreign- born US residents— about 17 percent by then. But today many of the foreign- born are not citizens. Unless this situation changes, whites, even by the narrow and exclusive definition typically used in demographic data, will still be the majority of citizens at midcentury. And since nonwhite citizens tend to be younger than whites and hence more concentrated among children, nationally whites will be the majority of voters past 2050, even if Census Bureau population projections turn out to be exactly right … As we have seen, census data still do not allow us to identify the sizable group of Americans who are partly Hispanic and partly something else. Even more consequential are the standard ethno-racial classifications for the most widely disseminated data. They place mixed individuals in a separate category regardless of the components of their family backgrounds. This leads directly to formulations that they are not white and should be counted as minorities, even though many of them have a white parent. That a large number of the mixed group are still children compounds this problem. They are described in census data by their parents, who often want to acknowledge both sides of their children’s parentage. Consequently, the great majority of mixed children are counted by the census as “minority.” This distortion exaggerates the decline of the white population. For example, it obviously affects data about the ethno- racial composition of children, leading to false reports about the majority of infants, and of young children more generally, being “babies of color,” a one- sided depiction that fails to acknowledge the white parentage of the majority … Classifying mixed individuals in multiple categories will help Americans see that the apparently steep decline in the white population is partly, and ironically, a consequence of whites’ mixing in families with minority partners. That is, as whites and minorities have children together, their children, as we have seen, tend to be classified as nonwhites in publicly disseminated demographic data. The more whites mix, the more children there will be who are categorized outside the white group. There is something perverse about a demographic data system that converts some whites’ willingness to cross major ethno-racial boundaries in choosing a partner into data that alarm other whites about minorities becoming a population majority. Surely we can do better than this … The emergence of a new majority that includes whites, most mixed minority-white individuals, and some others of exclusively minority origins would be the most powerful refutation of the basic understanding of the majority-minority society. Instead of a society riven along ethno- racial lines, between whites and nonwhites, we could see a society divided between an increasingly multi- hued majority and others whose lives are more determined by their minority status.

In the next essay in this series, we’ll examine how science suffers when arbitrary racial categories are used in unscientific ways.

"In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a grassroots movement of interracial couples and the children of such couples arose." Correction: You should add multiracial ADULTS to that coalition. It's harder for the opponents of the Multiracial Movement to attack the right of adults to identify as they please and reject the "one drop" nonsense so perversely dear to black-identified elites. Some "scholars" write articles for academic journals accusing "white mothers" as the designated villains supposedly trying to rob blacks of the mulattoes they consider their property. That is propaganda designed to mislead the ignorant into not reading the writings of people who were activists in the Multiracial Movement.