Where Did the Racial Boxes People Check on Forms Come From? – Part 6

When arbitrary racial categories are used in unscientific ways, science suffers.

David Bernstein, in his book Classified: The Untold Story of Racial Classifications in America, describes the long, sordid history behind America’s current, arbitrary racial classification system. What happens when regulations require that those arbitrary classifications be used in unscientific ways?

As Bernstein writes:

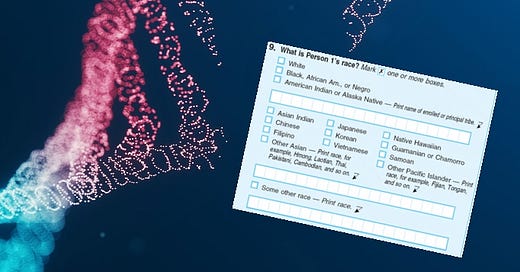

The standardized racial and ethnic categories developed in Statistical Directive No. 15 in 1977 came with an explicit warning these “classifications should not be interpreted as being scientific or anthropological in nature.” And indeed, the classifications have no valid scientific or anthropological basis. Yet the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) require medical researchers to classify study participants by Directive 15 categories. Participants are classified as Hispanic or non-Hispanic, and then “American Indian or Alaska Native,” “Asian,” “Black or African American,” “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander,” or “White.” The researchers must then report study results sorted by those categories … Directive 15 categories have unique problems, but scientists have pointed out a range of more general problems with using common racial categories in scientific and medical research. First, the phenotypes we associate with the different races, such as skin color and facial features, “simply do not correlate with data from the whole genome.” They also “do not correlate well with biochemical or other genetic characteristics.” … [A]s DNA testing has become more available and much less expensive, race is a poor substitute for looking at discernible human genetic differences. Rather than focusing on race, critics argue, researchers should look for the genetic markers that cause a treatment to be more effective or dangerous in certain populations. Those insights can then be applied on an individual rather than group basis … [T]he specific Directive 15 classifications mandated by the FDA and NIH are too arbitrary and indeterminate to be useful … Directive 15’s racial categories mask vast genetic differences within each category. The Directive 15 white category includes everyone from Scots to Greeks to Moroccans. Within the group classified as white, DNA studies find that people from the Middle East can be divided into four separate populations, and Europeans divided into eight separate populations. The white category is of “little value in gauging ethnicity or race” in a way that could be scientifically useful. People of black African descent, another Directive 15 classification, are highly genetically diverse, much more so than Europeans. A category based on black African origin cannot adequately “capture the complexity of migrations, artificial boundaries, and gene drift” in Africa. Somalis, for example, “are genetically more similar to people in Saudi Arabia than they are to people from other parts of Africa.” Saudis, meanwhile, are “White” under Directive 15 classification rules but are closer genetically to Somalis than to Norwegians. Most Ethiopians, whom Directive 15 categorizes as Black/African American, belong to the same genetic cluster as Ashkenazic Jews and Armenians … [D]ata from Directive 15 categories can obscure more than they illuminate; there are vast differences in health measures among subgroups of the Directive 15 categories … As Francis Collins, later director of the NIH, remarked, “We must strive to move beyond these weak surrogate relationships and get to the root causes of health and disease, be they genetic, environmental or both.”

Bernstein points out yet another issue that arises when using arbitrary racial categories in science:

Yet another problem with using race in medical practice involves the gaps between people’s self-perceptions of ethnic identity and how others perceive them. Emergency physicians often provide healthcare to individuals who are unconscious or otherwise nonresponsive. These patients cannot state their ethnic background, so their physicians decide based on appearance. But appearances can be deceiving. A study by the National Center for Health Statistics found that 5.8 percent of people who identify as African American were perceived as white by census interviewers. The same study found that one-third of self-identified Asians and 70 percent of self-identified Native Americans were perceived by census interviewers as being white or black. In another study of people who self-identified as Native American, 95.9 percent were classified as white by funeral directors on their death certificates, 4.1 percent as black, and none as Native American. Interviewers classified 61 percent of self-identified Native Americans as white and 37.8 percent as black.

Not only is the use of arbitrary racial categories not helpful to science, it can set it back. As Bernstein writes:

The need to satisfy FDA and NIH rules can also slow down important biomedical research, ultimately costing lives. In fall 2020, Moderna announced it was slowing enrollment in its clinical trial of a COVID-19 vaccine to ensure it had sufficient minority representation among study participants. As thousands of people worldwide were dying of COVID-19-related ailments, Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel made the remarkable assertion that diversity in research subjects “matters more to [Moderna] than speed.” NIH director Francis Collins later revealed that Moderna was not acting autonomously but rather under his direction. He told Moderna that it needed to recruit more “people of color” (i.e., people other than non-Hispanic whites), before NIH would acknowledge the vaccine’s safety. Collins said this even though there was no reason to believe that the vaccine would have a different safety and efficacy profile based on ethnicity. Even if there had been reason for such concern, the broad, crude Directive 15 categories Moderna was required to use would not be a scientifically valid way of finding such differences. The “Hispanic” category, with a primarily European genetic base with large admixtures of Indigenous and African ancestry, is a particularly scientifically arbitrary category to use in this context.

This didn’t have to be the case:

Civil rights groups initially hesitated to demand representation for racial groups in medical research. The existence of clinically significant biological differences among racial groups was hardly obvious. Indeed, suggesting such differences exist might play into racial prejudices … [But in] 1993, women’s health advocates persuaded Congress to take up legislation requiring federally funded researchers to enroll more women in medical studies. As the legislation proceeded through Congress, the Congressional Black Caucus persuaded the sponsors to add the phrase “and minorities” to the bill’s language about women. No significant consideration was given to whether purported racial differences were analogous to male-female biological differences … NIH-funded researchers who carefully identify study participants by more scientifically salient criteria still must aggregate their findings into the approved Directive 15 categories. Researchers must do so even if the subsamples of each group are too small to have statistically significant results and even when race has nothing to do with the purpose of the studies. As one critic has noted, the “NIH policy is a de facto mandate to insert race as a relevant biologic statistical variable in all medical research.” … Judith Molt of AstraZeneca observed that Directive 15 categories do not match scientific/anthropological categories. “The whole concept of ‘race,’” she explained, has been superseded by “a new understanding of the human genetic code.” We have learned “that the genetic differences between two person [sic] of the same race or ethnicity is just as great as between two persons of different race or ethnicity.” Conclusions derived from using the Directive 15 categories to analyze study data would therefore be unreliable. The result of relying on those conclusions, Molt warned, would be decreased patient safety. Gillian Woollett of the Biotechnology Industry Organization explained that Directive 15 categories “pre-date the work of the Human Genome Project, and reflect social, not scientific, categories.”

As Brian Villmoare writes in The Evolution of Everything: The Patterns and Causes of Big History:

When examining racism in the world today, the main question is: Who has something to gain? Racism is always found in cases where one group has something to gain or lose and sees racism as a way to gain. Are people afraid of losing jobs or status? Who gains economically or politically by making the racist claims? Ultimately, the various racial categories (typologies) reflected more about the writer (and their social prejudices) than any underlying biological reality … As with any form of racism, racial typology is a means to a political or economic end rather than any reflection of underlying biological reality. By the 1960s racial typology had been rejected by most scientists, especially within academic disciplines like biological anthropology. However, some of it remains today in medicine, where there are still contexts where people are categorized by “race.” Although these uses are not typically framed in terms of “racial superiority,” they can have detrimental effects because of the essential inaccuracy of using these outmoded categories that do not reflect the underlying pattern of biological variation.

Bernstein concludes with some final thoughts:

Official and racial ethnic classifications in the United States are self-fulfilling. The classifications encourage people to think of themselves as members of racial and ethnic categories that were invented or at least officially established and promoted by the government. For example, fifty years ago few Americans thought of themselves as Hispanic or Asian American; neither term was in common use, nor was there much intergroup solidarity among the national origin groups within those categories. The fact that many Americans self-identify with those categories is mostly a result of the government officially adopting these classifications in Directive 15.

In other words, the more people are required to check themselves into boxes, the more they’ll come to think they are indeed the box.

Bernstein again:

Beyond discrimination-monitoring, just as the United States has managed religious diversity via the separation of church and state, it could similarly manage ethnic diversity via the separation of race and state. The late Justice Antonin Scalia argued for this rule, constitutionally enforced. Scalia declared in one judicial opinion that “in the eyes of government, we are just one race here. It is American.”

The Biden Administration is considering not only perpetuating an official racial classification system, but also increasing the ways in which Americans are Balkanized. As John Early writes:

The Biden administration is proposing to issue a new directive on how U.S. agencies collect and publish data on race and ethnicity. … [T]he proposed directive, issued by the Office of Management and Budget in January [2023] … would increase the number of primary racial groups for data collection to seven from five. First, it would split the current category of “white” into two—one called “white” for people with European ancestry and another called “Middle East and North Africa,” or MENA. Second, it would redefine “Hispanic”—currently an independent ethnic classification—as a race … Respondents to government surveys or forms would be asked to select one or more races from the list. This would replace the current method by which people are first asked whether they are “Hispanic or Latino,” and then asked to select races from the original five options. Besides increasing the number of primary races, the directive would require that most racial data be collected at finer levels of detail, typically specifying a person’s country of origin and sometimes an ethnic group within or across countries such as Hmong, Roma, Bantu or Kurdish. Among those listed as black or African-American, it would require classifying separately descendants from slaves in the U.S. Descendants of Caribbean or Latin American slaves would be classified only by the country from which they or their ancestors immigrated. The proposed OMB directive claims to be for obtaining self-identification, but in practice government officials apply it to determine eligibility for benefits such as those from the Small Business Administration. Despite the directive’s statement that “the categories are not to be used for determining the eligibility of population groups for participation in any Federal programs,” in other places it says otherwise: (1) “Data could be used to allocate program or initiative benefits”; (2) the proposal “provides a minimum set of categories that all Federal agencies must use regardless of the collection mechanism (e.g., … program benefit applications)”; (3) “MENA population counts could be used to allocate needed resources”; and (4) “foremost consideration should be given to data aggregations by race and ethnicity that are useful for statistical analysis, program administration and assessment, and enforcement” (emphasis added). The bureaucracy behind this proposal is focused on being able to control, reward and punish the population by racial classification. American history doesn’t reassure us that such classifications are benign … Government collecting and acting on individuals’ beliefs about their race or ethnicity is antithetical to America’s founding principles. We are a country of “all men are created equal” and “e pluribus unum.” This initiative is trying to create even more categories by which people can be divided, separated, discriminated against or given special favors. When government collects and classifies individual data by personal racial and ethnic characteristics, it lays a foundation for discrimination, even oppression. Current census data show about 20% of new marriages are between people of different races or ethnicities, and for some groups almost half cross racial or ethnic lines. OMB uses this trend to justify collecting more data on race to accommodate “a growing number of people who identify as more than one race or ethnicity.” The office misses the point of its own argument. If a growing proportion of the population has multiple racial or ethnic roots, that means when establishing the most intimate and significant of human relationships—the family—race and ethnicity are becoming less important. Why, then, should government insist not only on keeping the distinctions alive but also on reinforcing and expanding them? It is time to stop discriminating by race in our statistics. Treat people as individuals, not merely parts of groups.

As the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism (FAIR) has written about these proposals:

FAIR strongly opposes each of these changes, and we urged the OMB to reconsider them. Our primary suggestion to the OMB is to fully and completely cease collecting data on individuals’ race and ethnicity altogether. If race and ethnicity data is no longer collected, the OMB will not be able to implement initiatives that are based on race and ethnicity, which often serve as a crude proxy for the actual problems that need to be comprehensively addressed. Ideally, the federal government would aspire to implement programs based on the actual needs of individual citizens that are determined based on a wide ranging set of criteria rather than based on immutable characteristics. This would be in keeping with the spirit and substance of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 … As a nation, we should be striving to do away with the racial classifications that have created so much harm throughout our history. Unfortunately, the OMB’s proposed directive will only further entrench this system of racial classification and perpetuate division. We hope the OMB will recognize this proposal as a mistake and rescind it immediately.

This concludes this series of essays on where the racial boxes people check on forms come from.

The next several essays will explore some of the topics we’ve examined before, but with new information and context, supplementing previous essays with new data I’ve come across since the previous essays were published.

Paul, As a scientist this entire house of cards becomes increasingly depressing. But important to read. Many thanks.