The Two-Parent Privilege – Part 9

Declining rates of marriage and falling birth rates, and international comparisons.

Continuing this essay series on the benefits to children of two-parent families, this essay will explore declining rates of marriage and falling birth rates, and international comparisons.

As economist Melissa Kearney writes in her book The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind:

The annual birth rate in the United States has been falling steadily, and sharply, since 2007, a break from a long period of generally stable annual birth rates. For the almost three decades between 1980 and 2007, the US birth rate hovered between 65 and 70 births per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. The birth rate followed a predictable cyclical pattern: falling during economic downturns and rebounding during economic recoveries. But around the time of the 2007 Great Recession, something changed—the birth rate fell precipitously, as one would expect in a recession, but then it never recovered when the economy improved. Instead, the US birth rate has continued a steady descent. As of 2020, the US birth rate was 55.8 births per 1,000 women between the ages of 15 and 44. (Over this same 40-year period, the number of abortions in the US has also steadily fallen. The recent drop in births reflects a decline in pregnancies, not a rise in abortions.) … Individual women are also having fewer kids than they used to. The average number of children a US woman is expected to have over her lifetime is now substantially below 2, which is the number required to keep the US population from shrinking (without an increase in immigration). That is a separate issue in terms of the demographic and economic challenges it poses for the country— namely, a shrinking workforce and the challenge of continuing to fiscally support programs like Social Security and Medicare. For all the talk of these programs’ challenging finances, their greatest threat may come in the form of fewer people paying into them.

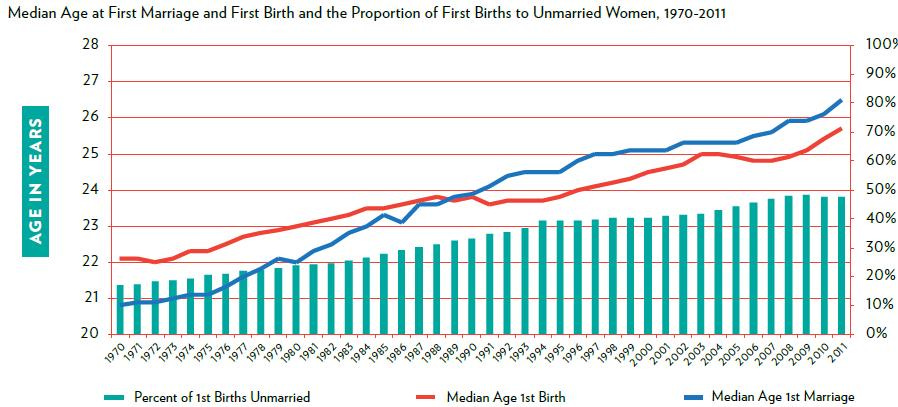

Marriage is also now less and less associated with raising children, as the median age at first marriage now exceeds the median age at first birth for women generally.

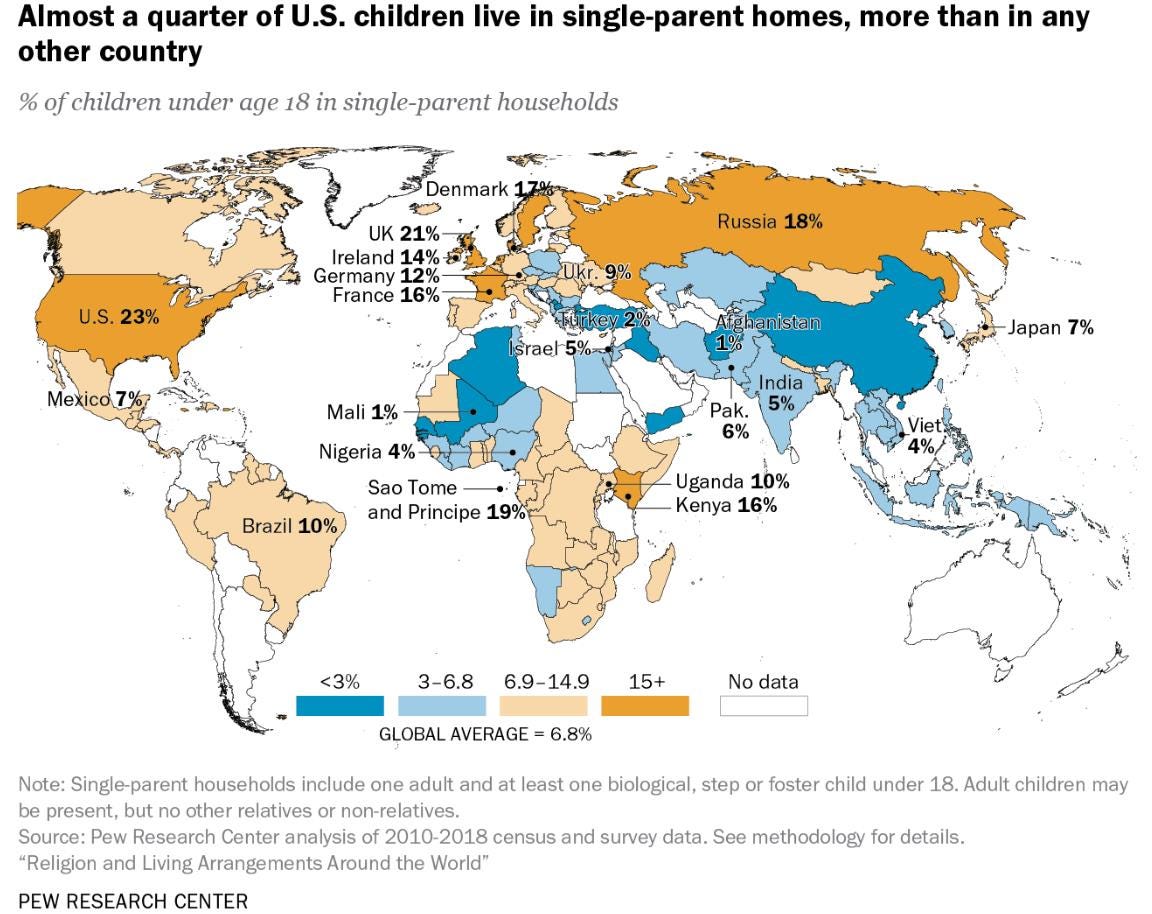

This dramatic rise of single-parent families in American is an outlier based on international comparisons.

As Pew has reported, for decades, the share of U.S. children living with a single parent has been rising, accompanied by a decline in marriage rates and a rise in births outside of marriage. A Pew Research Center study of 130 countries and territories shows that the U.S. has the world’s highest rate of children living in single-parent households. Almost a quarter of U.S. children under the age of 18 live with one parent and no other adults (23%), more than three times the share of children around the world who do so (7%).

Kearney writes:

Children in the United States are far more likely to live with only one parent than are children in other countries … [In 2019] Pew estimated that 23% of US children under the age of 18 live with one parent and no other adults—more than three times the share of children around the world who live with just one parent (7%). In Canada, the rate is 15%; in Mexico, it is 7%.

In a comparative analysis of 15 European countries and the United States, it was found that the U.S. “stands out as an extreme case with its very high proportion of children born to a lone mother, with a higher probability that children experience a union disruption of their parents than anywhere else, and with many children having the experience of living in a stepfamily.”

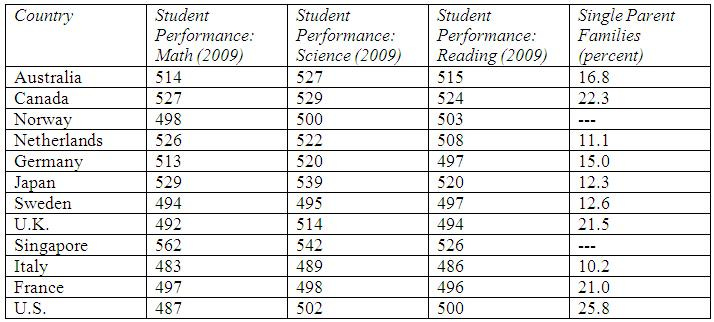

America’s status as an outlier internationally regarding its share of single-parent families is associated with its comparably lower international rankings on student test scores. The following chart compares student test performance by country to each country’s percent of children in single-parent families, as of 2009.

In summary, Kearney writes:

In recent decades, more and more American children are growing up with only their mother in the home. A second (mistaken) idea that people might have about this trend is that it is driven by economically successful women—women who make a great deal of money on their own and thus don’t need a spouse to help. In fact, single mothers are disproportionately neither college educated nor high income … Here are some of the key facts those data show:

• More than one in five children living in the US today live in a home with an unpartnered mother, meaning a mother who is neither married nor cohabitating. A majority of these households do not include another adult, such as a grandparent or other relative.

• A “college gap” in family structure has emerged over the past four decades. Currently, 12% of children whose mothers have a four-year college degree live with an unpartnered mother. A whopping 29% of children whose mothers don’t have a college degree and 30% of those whose mothers don’t have a high school degree live without a second parent in their homes.

• This college gap exists among White families, Black families, and Hispanic families. Asian families are an exception, with uniformly high rates of two-parent families across all education groups.

• The rise in unpartnered-mother households has been driven by an increase in the share of mothers who are never married—not by a rise in divorce rates or in unmarried cohabitating couples.

• US children are more likely to live with only their mother than children around the world are.

• The widening college gap in family structure over recent decades has amplified widening earnings inequality …

We are living in a vicious cycle: the forces that have eroded the economic position of non-college-educated men are now having widespread, multifaceted effects on families and how children are raised. These affected children are straddled with disadvantages that make it harder for them to flourish. The changes in family structure lead to further inequality and cement class gaps across generations … [W]hen I look at the data and evidence that have piled up over decades and across disciplinary fields, I am convinced that it is a conversation people in the US need to have. What those data say, overwhelmingly, are that children’s outcomes in life are profoundly shaped by their family and home experiences. Children who have the benefit of two parents in their home tend to have more highly resourced, enriching, stable childhoods, and they consequently do better in school and have fewer behavioral challenges. These children go on to complete more years of education, earn more in the workforce, and have a greater likelihood of being married … This family gap contributes to class gaps in childhood resources, experiences, and outcomes. It simultaneously reflects and exacerbates inequality. It undermines social mobility. It perpetuates divisions that are causing fragmentation and fractures in society. And it is part of a cycle that will have to be broken if class gaps are going to shrink and children from all backgrounds are going to have anything close to equal opportunities to get ahead, to thrive, and to live their best life.

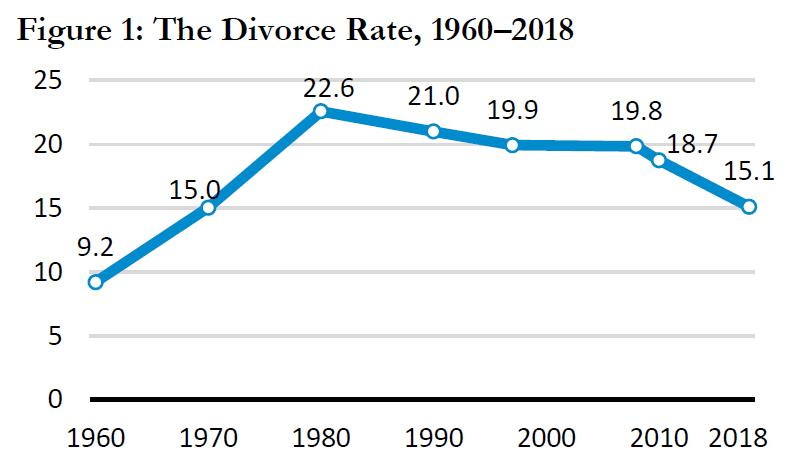

But there are some positive signs. As summarized by Brad Wilcox in 2020:

There is good news about marriage and family life in America; news that is underreported and not well-known by the general public. First, as Figure 1 indicates, divorce is down more than 30 percent since the height of the divorce revolution in 1980, and it seems to be headed lower … Less divorce and nonmarital childbearing equal more children being raised in intact, married families. In fact, as Figure 2 shows, since 2014, the share of children being raised in an intact, married family has climbed from 61.8 to 62.6 percent. An uptick in children living in intact families has been strongest for black children and children born to disadvantaged mothers, as Figure 3 suggests. The good news about family in America, then, is that a growing share of children are being raised in intact, married families … children born to cohabiting couples are almost twice as likely to see their parents break up, compared to children born to married couples, even after controlling for confounding sociodemographic factors such as parental education. Figure 4, which displays the likelihood that children will see their parents break up by age 12 for different levels of education and different relationship statuses, is emblematic of the superior stability of married families in America … Figure 5 indicates that children living in single-parent homes are at least two times more likely to be in poverty compared to children in married-parent families.

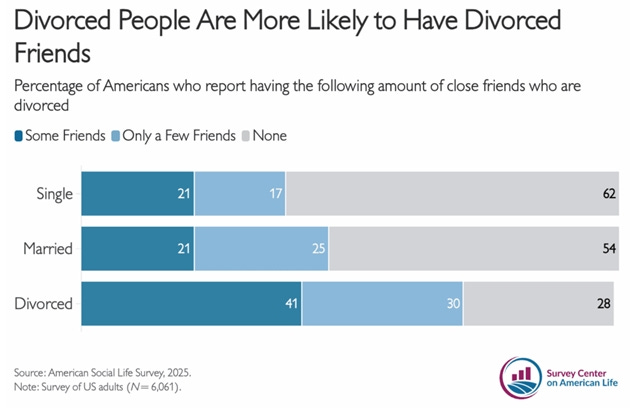

Having friends who are divorced significantly increases the chances a person will get divorced themselves. As Brad Wilcox writes:

Our social environment—the people we hang around—profoundly influences our behavior. People who hang out with smokers are far more likely to take up smoking themselves. Research has shown that if a friend gets divorced, your odds of also getting divorced increase dramatically. In one study, the authors looked at several decades of marriage and divorce records among Massachusetts residents, finding that your odds of getting divorced increase by 75 percent when a friend gets divorced. Even more distant relationships can influence marital success. When a friend of a friend got divorced, there was a significant uptick in divorce likelihood. That’s a remarkable finding. Our research is consistent with this type of social clustering. If you are divorced, you are far more likely to have a close friend who is also divorced.

That concludes this series of essays on the benefits to children of two-parent families.

Paul, once again thank you. I have learned a great deal from this particular series in an area to which I never gave much thought. Interesting, perhaps, how this squares with the Irish repudiation of family erosion in yesterday's constitutional vote. Perhaps there is hope.