Continuing this essay series on the benefits to children of two-parent families, this essay will explore whether or not American society has crossed a Rubicon of sorts, as returning to a social ethic of marriage becomes increasingly more difficult.

As economist Melissa Kearney writes in her book The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind:

If the eroding economic position of non-college-educated men is driving these trends [trends of decreased marriage rates], then one could reasonably conclude that an improvement in the economic position of less educated men might help reverse these trends. That’s what I thought, anyway, until I studied how recent increases in male employment and earnings prospects influenced family formation. The results of that research cast doubt on the notion that an improvement in men’s economic position will necessarily increase marriage rates. The fracking boom of the first decade of the 2000s, which gave rise to economic booms in US towns and cities where they wouldn’t have occurred otherwise, provided a rare opportunity to investigate whether an improvement in the economic prospects of men without a four-year college degree would lead to a reduction in the nonmarital birth share. In a 2018 study that I wrote with my coauthor Riley Wilson, we used the fracking boom to test a “reverse marriageable men” hypothesis. I say “reverse” because this research was centered on the possibility that an improvement in men’s economic position would lead to an increase in marriage rates and a reduction in nonmarital childbearing—effectively the converse of William Julius Wilson’s marriageable men hypothesis. The research represented a rare opportunity because in recent decades, most secular changes—including increased imports from China, the adoption of robots in workplaces, and the decline in union representation—have weakened the economic position of men without four-year college degrees in the United States, without any predictable vector for reversal. The fracking boom, and its impacts on men’s wages and economic position, was a notable exception. The practice of fracking in rural communities—extracting oil and gas from underground rock formations—has been associated with more jobs and enhanced income in those communities. The ability of communities to engage in such activity is almost entirely driven by geographic factors buried deep in the earth. This limitation creates an ideal experiment from the point of view of econometric research: there is no other reason why the geological conditions of a place would predict a sudden change in family formation and fertility outcomes around 2005. Any changes we see in these outcomes are likely attributable to the economic changes associated with the fracking of those geological shale plays. The study found that local fracking activity between 1997 and 2012 (the incidence of which was arbitrary, or at least determined in part by geology) led to an increase in employment and earnings among non-college-educated men—not just in oil and gas extraction jobs, but in other industries as well, consistent with the existence of broader job-creation effects from local fracking activity. Although there was no discernible increase in employment among non-college-educated women, the data suggest that earnings went up for these women, albeit only by half as much (on average) as for non-college-educated men. Wilson and I investigated whether this improvement in non-college-educated men’s employment and earnings prospects—both in absolute terms and relative to women—had also led to an increase in marriage among young adults (ages 18 to 34) or a decrease in the share of births to unmarried women. Our first finding was that these local fracking booms led to overall increases in total births, an increase of roughly 3 births per 1,000 women. This result was consistent with the known effects of income on birth rates established by earlier research across many contexts: when people experience an increase in income or wealth, they tend to have more children. Why does more income lead people to have more children? It’s impossible to generalize this in universal terms, but research supports a conclusion that, in a nutshell, most people generally want to have kids, but kids are expensive. So when people get more income, they are more likely to have a child or more children than they otherwise would. This finding was an important takeaway from our study, but it wasn’t really the point of it. We wanted to know how the share of births to unmarried mothers changed when there were more jobs and higher wages available for men. To our surprise, the increase in births associated with fracking booms occurred as much with unmarried parents as with married ones. The “reverse marriageable men” hypothesis, which predicted that improvements in the economic circumstance of men would lead to an increase in marriage and a reduction in the share of births outside marriage, was not what the data showed. More babies were being born, but they were being born to an approximately unchanged share of unwed parents. Though fracking activity led to an increase in employment and earnings for men, which in turn led to an increase in births, it did not have any effect on the percent of adults ages 18 to 34 who were newly married, never married, or currently married. Nor was there any change in divorce or cohabitation rates. We wondered: Why not? If the trend toward unwed births had correlated so closely to diminished economic standing among men, wouldn’t the reinstatement of their earlier stature have produced at least some return to the earlier mode of marriage and children? One possibility was (and is) that the social norms surrounding childbearing and marriage have changed enough that men and women didn’t feel the need to get married, or the desire to get married, even if the man had a well-paying job and the couple had a baby together.

Kearney then describes a test of that hypothesis:

To investigate whether social norms might help explain the family-formation response in the context of the local fracking booms, Wilson and I proceeded to examine whether the response to the sudden economic shock was different in places where nonmarital childbearing was more and less common. It was. In places where very few births occurred outside marriage before the start of fracking, the local fracking boom led to a sizable increase in births only to married women, not to unmarried women. In places where a sizable share of births occurred to unmarried women before the fracking boom, the economic boom led to relatively equal increases in births to unmarried and married women … To further investigate this theory that social context matters to how births proceed, Wilson and I revisited the economic and demographic data surrounding the Appalachian coal boom and bust of the 1970s and 1980s. The economic shock brought about by the coal boom was very similar to that of fracking, but it occurred during a period when it was much less common—and much less socially acceptable—to have a child outside of a marital union. An earlier economics study, published in 2013, had shown how the coal boom and bust of the 1970s and 1980s led to an increase, then decrease, in men’s incomes in the Appalachian coal-mining region of the United States, which in turn produced a similar pattern of increase and decrease in births to married couples. This prior finding led the researchers to frame their study in interesting terms: are kids “normal goods,” i.e., things people have more of when they have more money? For married couples in these coal towns, the answer appeared to be yes. Wilson and I revisited their work and historical context to investigate whether unmarried couples also had more kids when their income went up on account of the coal boom. Unlike what we found during the fracking boom, the answer was no. But the increase in male earnings associated with the coal boom of those earlier decades did lead to an increase in marriage. The contrast in how people responded to having more money from the coal boom of the 1970s and the fracking boom of the first decade of the 2000s is consistent with the notion that social context matters. In the earlier period, when nonmarital births were still far from the norm, couples responded to an increase in earnings by getting married and, if married, having more kids. But there was no increase in births among unmarried women; social norms were such that women didn’t do that. In the later period, both marital and nonmarital births increased in response to the economic shock. And unlike during the Appalachian coal boom, there was no discernible increase in marriage in response to the economic benefit associated with fracking. Our study suggested that, in a time when an increasing share of kids are born to unmarried parents, there may be no going back—at least not through economic changes alone … Now that nonmarital childbearing has become fairly common, we are likely in a new social paradigm. Reversing recent trends in family structure will likely require both economic and social changes.

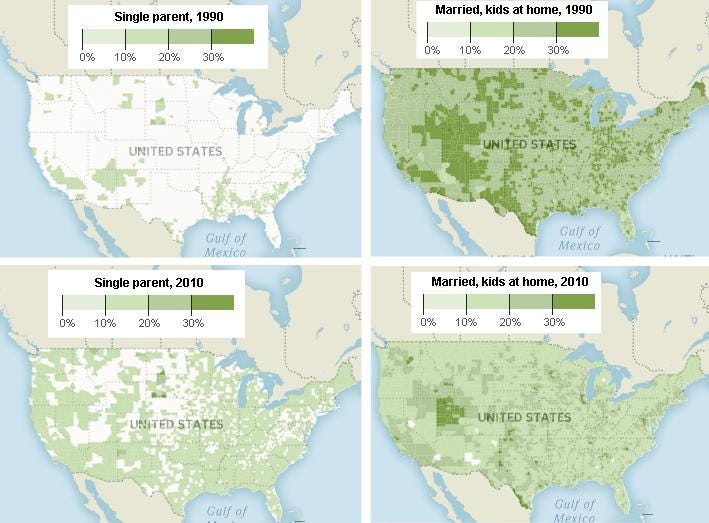

Even going back a decade, the increased prevalence of single parent homes had permeated the American landscape. The maps below, taken from census data from 1990 to 2010 and printed in the Washington Post over a decade ago, show increases in the population density of single parents (left side maps) and decreases in the population density of married couples with kids at home (right side maps).

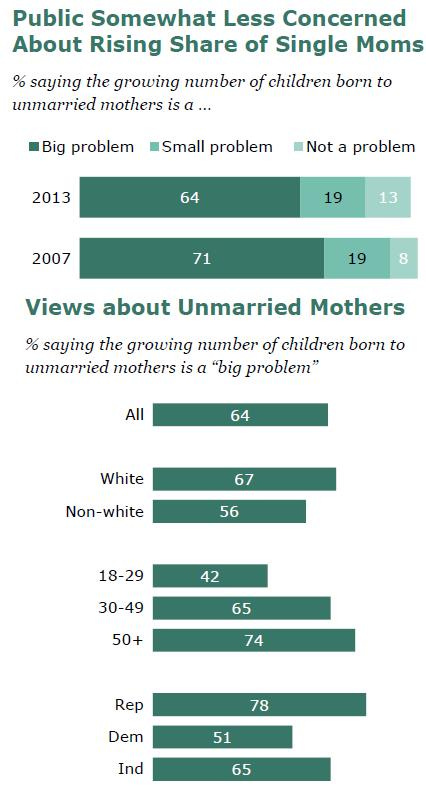

Fewer people today believe the growing number of children born to unmarried mothers is a problem. Still, significantly more Republicans and Independents, and people over 30, believe it is a problem.

The percentage of 12th graders who have less than two parents in the home has increased significantly.

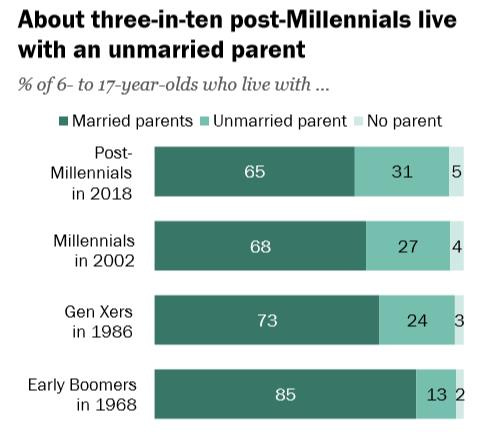

And more generally, young people in the post-Millennial generation are more likely to live with an unmarried parent than young people in previous generations.

Still, although those young people in so-called “Generation Z” (consisting of people born after 1995) generally hold substantially left-of center opinions on a variety of issues, greater numbers of them believe it is a bad thing for society when single mothers raise children on their own (although such views are still the minority view).

In the next and final essay in this series, we’ll explore the relationship between declining rates of marriage and falling birth rates, and international comparisons.

Paul, Another thing I did not know. One wonders what the implications of this beyond just the child-rearing components might be. All kinds of questions are raised by this shift in couples vs individuals -- especially considering the novelty in the historic context. Many thanks.